By Dr. Chelsea Davis

Scholar of Literature

Writer and Critic

This article, Sick Doctors: Suffering and Sadism in 19th-Century America, was originally published in The Public Domain Review under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0. If you wish to reuse it please see: https://publicdomainreview.org/legal/

On one page [of George Lippard’s novel Ladye Annabel] you read a most graphic and minute description of breaking a criminal on a wheel, told by the executioner, with the same sort of cool gayety with which a parish doctor may be supposed to probe the wounds of charity hospital sufferers. Then, again comes a harrowing recital of the way they tore men to pieces with wild horses, dragging the four quarters of the wretch to as many four points of the compass; . . . [it is] enough to make the fortune of a race of small-fry Monk Lewises . . . [Lippard] pre-suppose[s] a morbid appetite or perverted taste, on the part of the buyer.

Motley Manners, 1848 review of George Lippard’s Ladye Annabel; or, The Doom of the Poisoner.1

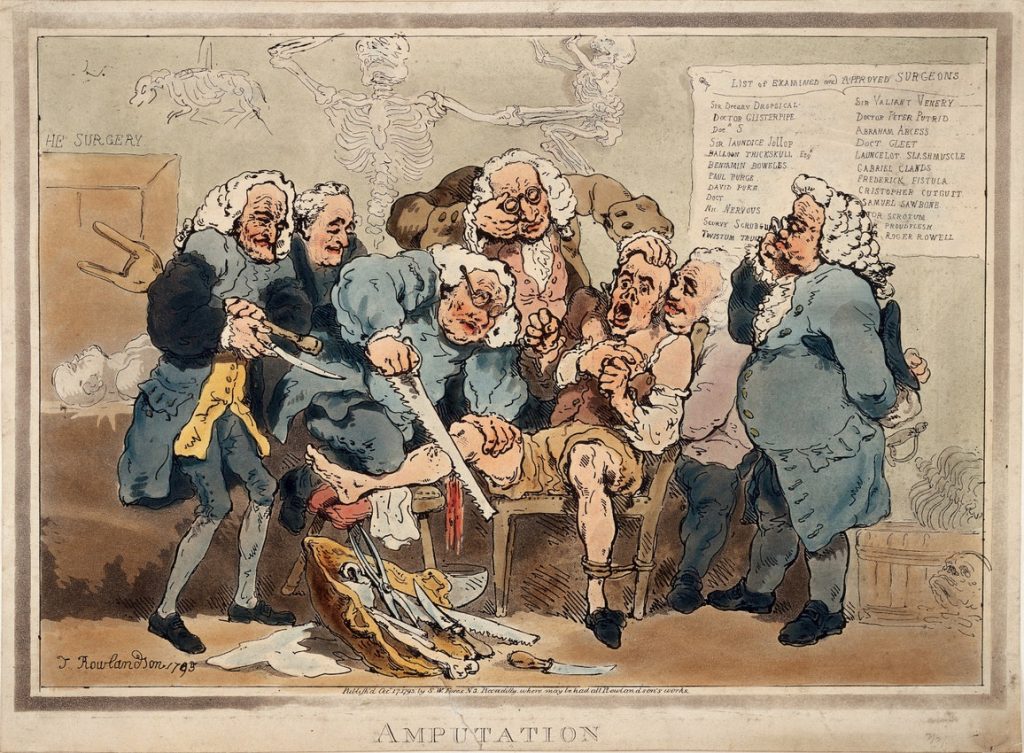

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before: a doctor, an executioner, and a fan of “perver[sely]” violent fiction walk into a bar, cheerfully chatting about their shared passion for torture. Not ringing any bells? That’s likely because popular views on medicine have changed radically since 1848, when the above passage was penned. These days, it would seem borderline blasphemous to group physicians — now regarded by most as healers and helpers, sworn to do no harm — with two avowed sadists who watch suffering for sport. (Such an analogy would perhaps seem especially inapt in 2020, as countless medical professionals continue to put their own lives on the line to care for highly infectious COVID-19 patients.) But as it turns out, this excerpt’s framing of physicians as barbaric — as the kind of men who finger painful injuries with the “cool gayety” of an expert torturer — would not have surprised many Americans in the nineteenth century. Far from it: the sicko doctor, whose fascination with the human body’s gory workings makes him creepily indifferent to his patient’s discomfort, routinely cropped up as a bogeyman in the fiction, political cartoons, and nonfiction of the antebellum United States.

To understand why this was the case, we might take a closer look at the above-excerpted review, which uses a metaphorical doctor to evoke a real ethical question that obsessed Americans at the time: the appropriate way to relate to other people’s suffering. In attacking Philadelphian provocateur George Lippard’s novel Ladye Annabel (1844), pseudonymous reviewer Motley Manners suggests that the book’s explicit portrayals of medieval torture bespeak a “morbidity” and “pervers[ity]” on the parts of its characters, writer, and reader alike. (Manners is no innovator here: the gruesome content of Gothic literature, which supposedly both appeals to and breeds creeps, has produced moral panics ever since its inception in the late eighteenth century — panics which live on in pearl-clutching condemnations of horror movies and fans today.) But what Manners seems to find even more unsettling than the Ladye Annabel executioner’s actual participation in wheel-breakings and drawings and quarterings is the character’s breezy attitude toward his bloody deeds — the “cool gayety” with which he recounts them.

The seeming paradox of this particular phrase, which mixes apathy with joy, would have seemed no paradox at all to a nineteenth-century reader. Americans of this epoch were preoccupied with the idea that there was a causal relationship between the two emotions — that feeling indifference toward the pain of others threatened to eventually become active pleasure in the pain of others. All it took to desensitize a given observer, the thinking went, was overexposure to suffering — the kind of daily saturation with groans and gore that are the everyday experience of a professional flesh-cutter like a torturer. Or a doctor.

In other texts of the period, the analogy between unfeeling doctor and unfeeling author becomes even more literal. The critic George Gifflan, for instance, speculated that the English writer George Crabbe, notorious for his unflinching portrayals of poverty and crime, had acquired the “perfect coolness” characteristic of his writings during his prior career as a surgeon. “As a medical man, [Crabbe] had come in contact with little else than man’s human miseries and diseases”, observes Gifflan, and the experience “materially discolored [Crabbe’s] view of life”. It is for this reason that Crabbe’s fiction was able to “feel … with firm finger the palpitating pulse of the infanticide or murderer—and snuff … a certain sweet odor in the evil savors of putrefying misery and crime”. Again, the sick doctor disturbs because of his “cool gayety”, his admixture of clinically appropriate objectivity with straight-up schadenfreude. A “firm[ness]” in the face of suffering could easily mutate into a predilection for the “sweet odor” therein.2

To make matters worse, it was not only his own character that the gore-benumbed writer/doctor ran the risk of damaging. Nineteenth-century thinkers worried he might also wound his reader/patient. Thus another critic used the same harmful healer metaphor to skewer George Lippard (the guy couldn’t catch a break), this time with regard to a different Gothic novel. Reflecting a broader Victorian conviction that art’s main imperative is to improve its audience’s moral character, this second naysayer complained that Lippard’s blood-spattered The Quaker City: Or, the Monks of Monk Hall (1849) made its readers less moral by repeatedly bludgeoning them with descriptions of bombastic violence. “In what estimation would we hold a physician who would order his patient, exhibiting slight symptoms of a contagious disease, to a place where the malady rages in its most malignant forms?” the review asks accusatorily.3

Nor was the twisted physician confined to the realm of critical metaphor: he also took the shape of a full-blown character in several novels of the period. Among the earliest is James Fenimore Cooper’s The Spy: A Tale of the Neutral Ground (1821), which recounts the late stages of the American Revolutionary War through the travails of the Wharton family, inhabitants of a region of New York state hotly contested by the American and British forces. The Whartons are alternately aided and terrorized by one Dr Archibald Sitgreaves, a surgeon serving the Continental Army. Dr Sitgreaves’ surname — conjuring the image of one who sits on graves — perfectly suits a physician whose fascination with grievous injuries renders him insensible to the physical and emotional feelings of his wounded patients. When Henry Wharton, a captain in the British army, sustains a minor arm wound, the physician informs him with perverse regret that the limb will not need to be amputated:

“…the hurt is not bad, but you have such a pretty arm for an operation; the pleasure of the thing might have tempted a novice.”

“The devil!” cried the captain [Wharton]. “Can there be any pleasure in mutilating a fellow creature?”

“Sir”, said the surgeon, with gravity, “a scientific amputation is a very pretty operation, and doubtless might tempt a younger man, in the hurry of business, to overlook all the particulars of the case.”4

Here, as elsewhere, Dr Sitgreaves’ oblivious bedside manner is as funny as it is revolting. But this does not mean that he lacks the capacity for seriously sadistic acts. At one point, having caught wind that the novel’s hero, Harvey Birch, is slated to be executed for espionage, Dr Sitgreaves rhapsodizes about his plans to turn Birch’s corpse into a sculpture as a gift for an aunt (“his bones are well knit. I will make a perfect beauty of him”). Later, he boasts that he once broke his own finger simply to watch it heal. “[T]he thrilling sensation excited by the knitting of the bone … exceeded any other enjoyment that I have ever experienced”, he tells a horrified listener. “Now, had it been one of the more important members, such as the leg, or arm, how much greater must the pleasure have been!”

Although Dr Sitgreaves has, for the time being, targeted only his own body for injury practice, his wistful reverie about the superior thrills of a broken “leg, or arm” gestures toward a ghastly escalation of medical violence. What atrocity might Sitgreaves not commit in pursuit of scientifically interesting spectacles? What stands in the way of his progressing from breaking fingers, to breaking arms, to breaking legs, to killing a man — especially if that man’s skeleton would make a “perfect” sculpture? The latter was no hypothetical nightmare for Cooper’s readers. Throughout the nineteenth century, the corpses of freshly dead Americans — often those of the poor, people of color, and criminals — were snatched up by medical schools for use as dissecting cadavers. This practice produced tremendous public ire toward surgeons, culminating in over a dozen “anatomy riots” from 1785 to 1855.5

The threat of the slippery slope of brutality — a slope down which Dr Sitgreaves has clearly already begun to slide — was central to nineteenth-century Americans’ anxieties over violent voyeurism. “The ‘taste’ for cruelty in … spectators was considered to be a ‘progressive vice’”, writes historian Karen Halttunen, “a ‘craving’ or ‘hunger’ that, like substance addiction … only grew more powerful as it was fed”.6 Thus in 1831 legal reformer Edward Livingston criticized the death penalty on the grounds that, although “human sufferings are never beheld, for the first time, but with aversion, terror, and disgust”, a person who frequently witnessed public executions eventually came to regard them as “a spectacle, which must frequently be repeated to satisfy the ferocious taste it has formed”.7 The Moral Advocate newspaper worried in 1821 that battle increasingly “dulled” a soldier’s instinctive horror of war, gradually poisoning his empathic capacities until he eventually took active “enjoyment [in] the most horrid scenes of carnage”.8 The presumed link between watching or reading about violence and enacting violence even seemed to come full circle in some instances, such as an 1833 murder committed by one Abraham Prescott, whose attorneys asserted that their client had been “agitat[ed]” into killing an acquaintance by reading the lurid trial transcript from a different murder case.9

The mounting fear of learned callousness was part of a broader preoccupation with suffering in the nineteenth-century US and England, a widespread “obsession with pain” that has led historians to dub the period the “Age of Pain”.10 Prior to the major innovations in anesthesia that marked the late eighteenth century, serious physical discomfort was a common and inalterable part of life. But as surgery and anesthesia grew more sophisticated, and doctors gained the ability to reduce more and more varieties of pain, it was no longer psychologically necessary for people to collectively embrace agony. Between 1772 and 1846 — the years marking the discovery of nitrous oxide and the first use of ether as a surgical anesthetic, respectively — Anglo-American culture developed a “new distaste for pain” that gradually “achieved the level of full revulsion and horror”.11

These improvements in pain technology produced two seemingly antithetical cultural responses in the States. On the one hand, the wildly influential philosophical and literary movement known as sentimentalism pursued the recent advances in anesthesia to their logical extreme, advocating for the reduction of pain in all spheres. Sentimental novels like Susan Warner’s The Wide, Wide World (1851) framed sympathy toward suffering as the utmost human virtue, and sentimental reform movements campaigned against brutality in the realms of slavery, the military, the schoolroom, and legal punishment. On the other hand, because nothing spells titillation like taboo, many Americans also increasingly sought frissons in the pain of others. This era saw a massive upsurge in the popularity of BDSM pornography, “penny press” newspapers that ran graphic accounts of gory crimes, and sensationalistic fiction in the US.12

Although the vectors of their interest in suffering may have been diametrically opposed, sentimentalists and sadists were equally fascinated by pain.13 And both camps found the cruel doctor to be a useful device for expressing, interrogating, or denouncing that fascination. The two critics who derisively compared Gothic novelist George Lippard to a perverted physician, for example, were using the same metaphor as the subject of their critique: the figure of the barbaric doctor looms large in Lippard’s most famous novel, The Quaker City; Or, the Monks of Monk Hall (1845). The grotesque Dr McTourniquet raves about various “beautiful” operations and the joys of public dissections (“quite a treat to the uninitiated”); a dentist punishes irritating clients by yanking their teeth with unnecessary force; the novel’s villain, Devil-Bug, is a voyeuristic torturer who calls his victims “patients” and sells pilfered cadavers to physicians.14 “Never a doctor of all the schools, with his dissecting knife in hand and the corpse of a subject before him, could have manifested more nerve and coolness” than Devil-Bug preparing to slaughter and maim, the narrator says.15

Yet when it comes to vicious physicians, Louisa May Alcott’s novella Hospital Sketches (1863) — an example of the theoretically gentler genre of sentimental fiction — gives Lippard a run for his money. A lightly fictionalized account of Alcott’s own experience as a nurse during the American Civil War, Hospital Sketches celebrates sympathy as one of the essential virtues of medical caregiving. But our protagonist, a nurse named Tribulation Periwinkle, also encounters the opposite — a chillingly cold-hearted surgeon in the DC military hospital where she is posted. Dr P., she writes,

seemed to regard a dilapidated body very much as I should have regarded a damaged garment … cutting, sawing, patching and piecing, with the enthusiasm of an accomplished surgical seamstress… The more intricate the wound, the better he liked it.16

What has caused Dr P.’s sadism? An overdose of observed brutality is once again to blame. Before taking up the Civil War posting where we meet him, Dr P. had previously served in the Crimean War (1853–56), and our narrator nurse conjectures that it is “through long acquaintance with many of the ills flesh is heir to, [that he] had acquired [his] habit of regarding a man and his wound as separate institutions”. In fact, this numbing process seems to be at work in multiple members of the hospital staff, and even Nurse Periwinkle herself admits that she is becoming a bit too attracted to the sights of surgery: “There was an uncanny sort of fascination in watching [Dr P.], as he peered and probed into the mechanism of those wonderful bodies”.17

War was not the only context in which doctors (and nurses) were bombarded with the sights and sounds of anguish. Even under ordinary circumstances in the early and middle decades of the nineteenth century, the suffering of others was the bread and butter of physicians’ day-to-day-life. Before ether entered the operating theater, “the emotional ability to inflict vast suffering was perhaps the most basic of all professional prerequisites” to becoming a doctor, writes historian Martin S. Pernick.18 It was with distinct pride that Rutgers medical student Asa Fitch described his own transformation, over the course of a few weeks, from a naïf who “recoiled” the first time he observed an amputation to someone who could now see a “tedious and painful operation” performed on a child and feel “none of the tenderness which I have always before felt on such occasions”.19 Little wonder that the public frequently complained about doctors’ callousness.20

A particularly scathing version of this complaint came from none other than Herman Melville. His novel White-Jacket; or, the World in a Man-of-War (1850) satirizes high-intellect, low-compassion medicine men in the form of the vile Cadwallader Cuticle, MD. As the head physician of the frigate whose adventures White-Jacket follows, Cuticle enjoys a reputation as “the foremost Surgeon in the Navy” and memberships in the world’s finest medical associations.21 But Dr Cuticle’s top-notch education in human anatomy seems to have also deadened him to human emotion, leaving him with a “heartlessness of a purely scientific origin”. By the time we meet him, Cuticle views his patients’ bodies as exciting opportunities for medical discovery (and career advancement) rather than sources of real suffering: “Surrounded by moans and shrieks, by features distorted with anguish inflicted by himself”, Melville’s narrator recounts, Cuticle “yet maintained a countenance almost supernaturally calm”.22

In keeping with the “mad doctor” stereotype that he embodies,23 Dr Cuticle’s relentless pursuit of medical knowledge ironically becomes its own kind of distracting passion, in some cases clouding his professional judgment more than basic human sympathy might have. Eager to show off for the Navy’s other surgeons, Dr Cuticle opts to amputate an injured seaman’s leg rather than to pursue the less invasive (but less impressive) cure that his colleagues recommend. The sailor suffers greatly during the procedure and dies almost immediately afterwards.

To be sure, Dr Cuticle’s brutality approaches the realm of caricature: much like The Spy‘s Dr Sitgreaves and The Quaker City‘s Dr McTourniquet, the White-Jacket doctor waxes poetic about the “beaut[y]” of the grisly surgeries he performs, and collects figurines of grotesque medical anomalies. Yet the novel does not present Dr Cuticle’s insensitivity as exceptional. Instead, this highly credentialed, highly callous doctor serves as just one of the novel’s several object lessons in the ways that positions of great social power enable abuse. Throughout White-Jacket, various Naval officers delight in controlling and punishing lower-ranking sailors with various humiliations, flesh-rending floggings (over which Cuticle impassively presides), and even death. “The Navy is the asylum for the perverse”, the narrator bluntly summarizes. The novel’s scandalized readers agreed. Corporal punishment reformers handed out copies of White-Jacket to members of Congress, who voted just a few months later to outlaw flogging in the Navy. Although contemporary scholarship has found no evidence that the distribution of Melville’s book materially shaped this legislative decision, popular rumor held for decades afterwards that the novel had indeed been the straw that broke flogging’s back.24

The longstanding myth that Melville’s violent novel abolished flogging suggests there may be an optimistic alternative to fiction’s violence-warped doctor: Americans’ hope that bombarding readers with imaginary cruelty could sometimes make them less cruel instead of crueler. But if the line between edifying and harmful depictions of gore sounds like a difficult one to draw, that’s because it was — and is. We continue to wonder how much exposure to brutality awakens people to the wrongs of the world, and how much deadens us to them.25 For the pain-obsessed sentimental culture that produced him, the ethically precarious doctor — whose position of authority and constant IV drip of human suffering might just as easily make of him a sadistic harmer as a saintly healer — was the consummate symbol of that contradiction.

Appendix

Notes

- Motley Manners, “New American Writers No. 1: The Author of The Quaker City”, Holden’s Dollar Magazine, Vol. 2 No. 1 (July 1848), 421–2.

- George Gifillan, “George Crabbe”,The Eclectic Magazine of Foreign Literature, Science, and Art (May 1847), 5.

- “George Lippard”,The Nassau Literary Magazine (April 1849), 189.

- James Fenimore Cooper, The Spy: A Tale of the Neutral Ground, ed. James P. Elliott et al. (New York: AMS Press, 2002), 110.

- Michael Sappol, A Traffic of Dead Bodies: Anatomy and Embodied Social Identity in Nineteenth-Century America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002), 3–5. Several times in the US, medical corpse-snatching even progressed to the level of “burking”, wherein criminals slaughtered perfectly healthy people in order to sell their cadavers on the black market.

- Karen Halttunen, “Humanitarianism and the Pornography of Pain in Anglo-American Culture”, The American Historical Review, Vol. 100, No. 2 (April 1995), 324.

- Remarks on the Expediency of Abolishing the Punishment of Death (Philadelphia: Jesper Harding, 1831), 10.

- “The Penitentiary System”, The Moral Advocate, A Monthly Publication on War, Duelling, Capital Punishment, and Prison Discipline, Vol. 1 No. 8 (Feb. 1822), 122.

- Report of the Trial of Abraham Prescott (M.G. Atwood, Currier, and Hall, 1834), 54. For a fuller analysis of this defense, see Karen Halttunen’s Murder Most Foul: The Killer and the American Gothic Imagination (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009), 119.

- James Turner, Reckoning with the Beast: Animals, Pain, and Humanity in the Victorian Mind (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1980), xii; Charles Peirce is quoted in James Turner, Without God, Without Creed: The Origins of Unbelief in America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1985), 205; David Morris, The Culture of Pain (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993).

- Halttunen, “Humanitarianism”, 310.

- Halttunen, “Humanitarianism”, 313.

- Critics such as Marianne Noble have gone so far as to call sentimental fiction downright “sadomasochistic”, contending that the genre takes pleasure in pain with no less enthusiasm than do Gothic narratives. See Noble’s “An Ecstasy of Apprehension: The Gothic Pleasures of Sentimental Fiction” in American Gothic: New Interventions in a National Narrative, ed. Robert K. Martin and Eric Savoy (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press), 164.

- George Lippard, The Quaker City: Or, The Monks of Monk-Hall: A Romance of Philadelphia Life, Mystery, and Crime (Philadelphia, 1847), 235.

- Lippard, 311.

- Louisa May Alcott, Hospital Sketches (Bedford: Applewood Books, 1986), 36. Alcott, 36.

- Martin S. Pernick, “The Calculus of Suffering in Nineteenth-Century Surgery”, The Hastings Center Report, Vol. 13 No. 2 (April 1983), 26.

- Qtd. in Samuel Rezneck, “A Course of Medical Education in New York City in 1828–29: The Journal of Asa Fitch”, Bulletin of the History of Medicine, Vol. XLII (November-December 1968), 561.

- So prevalent was this concern that Dr. Worthington Hooker dedicated much of an 1849 book to combatting the notion that “the physician, from his familiarity with scenes of distress, becomes unfeeling.” See his Physician and Patient (New York: Baker and Scribner, 1849), 385.

- Herman Melville, White-Jacket; or, The World in a Man-of-War (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1970), ed. Harrison Hayford, Hershel Parker, and G. Thomas Tanselle, 238. Cuticle’s combination of an impressive pedigree with an unimpressive capacity for empathy also reflects a Jacksonian-era suspicion of intellectual and social elites, such as medical practitioners. See Stephanie J. Browner, Profound Science and Elegant Literature: Imagining Doctors in Nineteenth-Century America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005).

- Melville, 241.

- For more on Cuticle as a “mad doctor”, see Browner 85. Scholarship on the medical man as Gothic villain has tended to focus on his appearances in British Gothic literature. See Sara Wasson, “Useful Darkness: Intersections between Medical Humanities and Gothic Studies”, Gothic Studies, Vol. 17 No. 1 (May 2015), 1–12 and William Hughes, Historical Dictionary of Gothic Literature (Lanham: Scarecrow Press, 2013), 11–12.

- Willard Thorp, “Historical Note”, in White-Jacket; or, The World in a Man-of-War, 427, fn. 31.

- This conundrum has arguably only gotten thornier in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, as our culture has become ever more saturated with sensationalistic images and film. For a survey of this evolution, see L. Andrew Cooper’s Gothic Realities: The Impact of Horror Fiction on Modern Culture (Jefferson: McFarland, 2014).

Public Domain Works

- The Spy: A Tale of the Neutral Ground, James Fenimore Cooper (1821)

- The Quaker City; or, The Monks of Monk Hall, George Lippard (1845)

- Hospital Sketches, Louisa May Alcott (1863)

- White-Jacket; or, The World in a Man-of-War, Herman Melville (1850)