Just as modern debates pit UFO enthusiasts against skeptics who prefer weather balloons or satellites, the medieval world oscillated between wonder and rationalization.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Medieval Europe and the broader Mediterranean world were no strangers to wonders in the heavens. Eclipses, comets, and meteors filled chronicles as markers of divine will, but not all reports fit neatly into those categories. Now and then, witnesses recorded fiery shields, aerial ships, or spheres of flame, strange phenomena that resemble what modern readers might call “UFOs.”1 Of course, for monks and chroniclers, the framework was never extraterrestrial visitation but omens, portents, and signs.

These reports, scattered across chronicles and annals, reveal something deeper than curiosity about lights in the sky. They display a cultural tension between wonder and skepticism, authority and observation. Some accepted them as divine messages, others allegorized them into lessons, while a few dismissed them as exaggerations. The story of medieval “UFOs” is therefore less about aliens than about the ways humans have always wrestled with the inexplicable.

Early Reports and the Origins of the Tradition

Among the earliest and most striking reports is the entry for the year 776 in the Annales Laurissenses minores. During the Saxon siege of the Frankish fortress of Sigiburg, witnesses claimed to see “the likeness of two large flaming shields” hovering in the sky above the church.2 The Saxons, terrified by this vision, broke off the assault, and Christian chroniclers recorded the event as a clear sign of divine protection.

Other traditions emphasize different images. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records in 793 that “terrible portents appeared over Northumbria, and these were immense whirlwinds, flashes of lightning, and fiery dragons flying in the air.”3 The chronicler tied these visions directly to the Viking raid on Lindisfarne that same year, reading the aerial dragons as signs of God’s wrath.

In Ireland, several annals between the ninth and eleventh centuries mention “airships” or “ships in the sky.” The Annals of Ulster for 748 CE describe ships sailing through the clouds, while later accounts added a bizarre anecdote of a sailor casting an anchor that became stuck in a church roof.4 Though strange, these stories spread widely and carried symbolic resonance.

Patterns quickly emerge. Strange aerial forms appeared most often at times of invasion, disaster, or uncertainty. Whether fiery dragons, shields, or ships, they functioned as warnings or confirmations of providence.

Believers and Enthusiasts

For many chroniclers, such reports required no skeptical gloss. They were signs and portents, woven into the providential fabric of history. The shields over Sigiburg confirmed divine support for the Franks. The dragons before Lindisfarne heralded the Viking terror. Believers saw no distinction between astronomy and theology, the heavens themselves spoke.

The Irish airship stories demonstrate this duality. To some monastic writers, they were allegories of spiritual truths, symbols of the Church as a ship sailing through the heavens. Others, however, repeated them with little allegorical framing, as though to affirm their literal occurrence. Popular imagination absorbed these tales, and they reappeared in sermons and folklore across centuries.

The appetite for marvels was also literary. Compilers of wonders, like later medieval encyclopedists, delighted in preserving such tales for their sheer strangeness. Their inclusion in chronicles, even without commentary, gave them a kind of legitimacy that reinforced belief.

Skeptics and Critics

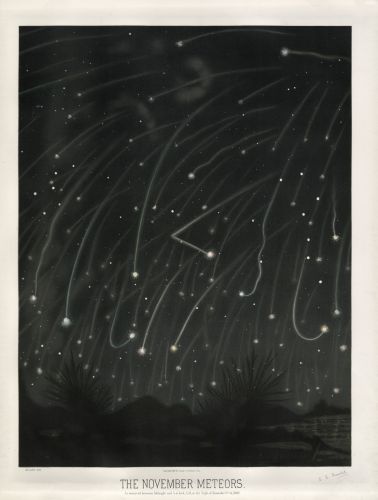

Yet skepticism was not absent. Some writers sought natural explanations. Isidore of Seville, in his Etymologiae, framed fiery aerial phenomena as the work of comets or burning exhalations in the upper air.5 He sought to categorize marvels within natural philosophy rather than simply record them as divine signs.

Later scholastic thinkers pushed this line further. Theories of atmospheric optics, meteor showers, and eclipses provided rationalist frames for reports of fiery spheres or shields. In the Islamic world, polymaths like al-Biruni and Ibn Sina criticized credulous acceptance of marvel tales, insisting that many were illusions, exaggerations, or misperceptions.6

Thus, while some preserved aerial marvels as signs of God’s hand, others worked to normalize them as natural events. To the rationalizing tradition, reports of ships in the sky were errors of imagination, not facts of geography.

The Persistence of Belief

Despite these skeptical voices, reports of aerial wonders persisted well into the late Middle Ages. In 1034, chroniclers at Basel described a “large sphere of fire” hovering over the church of St. Mary, terrifying the townspeople.7 The entry preserved the event without natural explanation, showing that the old appetite for marvels endured.

Even into the sixteenth century, continuity is visible. In 1561, the city of Nuremberg witnessed what was described as a “celestial battle,” recorded in a famous broadsheet by Hans Glaser. Spheres, crosses, and cylinders filled the dawn sky, interpreted by some as heavenly warfare.8 Though beyond the medieval period, the account demonstrates that the categories of fiery shields and aerial formations remained potent.

Why did such beliefs endure? First, the authority of chroniclers was immense. Monastic annals were treated as reliable witnesses, so their marvels carried weight. Second, theology required signs. In a cosmos suffused with divine meaning, unexplained aerial events could not be mere accidents. Finally, culture craved marvels. Tales of fire in the sky thrilled audiences, reinforcing their persistence across generations.

The Intellectual Divide

Belief in aerial wonders reflected more than credulity. To those who affirmed them, they were evidence of a universe alive with meaning. No celestial event was random; all could be interpreted as divine communication.

For skeptics, by contrast, such tales revealed the weakness of human perception and the dangers of uncritical reliance on tradition. They sought to replace wonder with reason, to translate fiery shields into comets and ships in the sky into allegory or illusion.

At the same time, the act of including or excluding these marvels became an intellectual marker. Chroniclers who preserved them aligned with the marvel tradition, honoring the authority of earlier texts and the appetite of audiences. Those who dismissed them claimed a different identity, one rooted in rationalist inquiry and empirical explanation.

Debates over aerial wonders thus mirrored larger contests over the sources of knowledge. Should truth rest on inherited texts, the witness of communities, or the judgment of reason? Reports of flaming shields or heavenly ships became battlegrounds for defining legitimate knowledge. They were as much intellectual controversies as they were descriptions of celestial phenomena.

Conclusion

Medieval reports of UFOs (fiery shields, dragons, spheres, or ships) remind us that the impulse to find meaning in the skies is timeless. They reveal a divide between credulous believers, allegorical interpreters, and skeptical critics, all struggling to interpret the unexplained.

Just as modern debates pit UFO enthusiasts against skeptics who prefer weather balloons or satellites, the medieval world oscillated between wonder and rationalization. To some, a fire in the sky was God’s hand. To others, it was an illusion. Across centuries, the common thread is human refusal to accept the sky as mute.

Appendix

Notes

- John Block Friedman, The Monstrous Races in Medieval Art and Thought (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1981), 233–40.

- Annales Laurissenses minores, s.a. 776.

- Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, entry for 793.

- Carey, John. “Aerial Ships and Underwater Monasteries.” Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium 12 (1992): 16-28.

- Isidore of Seville, Etymologiae, 3.29.

- Al-Biruni, Chronology of Ancient Nations, trans. C.E. Sachau (London, 1879), 46–47; Ibn Sina, Kitab al-Shifa (Book of Healing).

- Cited in Basel chronicles, 1034; discussed in Jacques Vallée, Passport to Magonia (Chicago, 1969), 18.

- Hans Glaser, Nuremberg Broadsheet, April 14, 1561.

Bibliography

- Al-Biruni. The Chronology of Ancient Nations. Trans. C.E. Sachau. London: 1879.

- Carey, John. “Aerial Ships and Underwater Monasteries.” Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium 12 (1992): 16-28.

- Friedman, John Block. The Monstrous Races in Medieval Art and Thought. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1981.

- Glaser, Hans. Nuremberg Broadsheet, 1561.

- Ibn Sina. Kitab al-Shifa (Book of Healing).

- Isidore of Seville. Etymologiae. Trans. Stephen A. Barney et al. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Annales Laurissenses minores. Monumenta Germaniae Historica.

- Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Trans. Michael Swanton. London: Phoenix Press, 2000.

- Vallée, Jacques. Passport to Magonia: From Folklore to Flying Saucers. Chicago: Henry Regnery, 1969.

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.19.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.