Small businesses in early America were more than economic units; they were institutions that shaped communities, politics, and national identity.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

From the colonial era through the early national period, small businesses played a foundational role in the economic, social, and political development of the United States. Far from being peripheral to the economy, these enterprises were the core around which local economies, communities, and even political movements coalesced. Small businesses in early America included artisans, shopkeepers, tavern owners, printers, and farmers, all of whom contributed to a complex and evolving economy that combined local self-sufficiency with increasing integration into Atlantic and global markets. What follows explores the origins, structures, and impacts of small businesses in early America, examining their roles in daily life, community identity, economic transformation, and early American capitalism.

Colonial Origins of Small Business

Small-scale commerce and artisanry were embedded in the colonial economy from the beginning. While subsistence farming remained the dominant occupation, a class of tradespeople, merchants, and craftsmen gradually emerged in towns and villages across the colonies. These individuals often operated their businesses out of their homes or small workshops, combining economic activity with domestic life.

Early American small businesses were shaped by British mercantilist policies and local circumstances. Colonial artisans, such as blacksmiths, cobblers, and coopers, served essential roles in their communities. Unlike large manufacturers in Britain, colonial craftsmen typically worked alone or with a few apprentices. Their businesses depended on local demand, seasonal fluctuations, and barter economies as much as on currency.1

Apprenticeship was the primary mode of skill transmission and business continuity. Young men (and occasionally women) entered into contracts that combined education with labor, often in the hope of eventually establishing their own shops. This system not only sustained skilled trades but also created networks of personal loyalty and community integration that extended beyond economic transactions.2

Economic Networks and Local Exchange

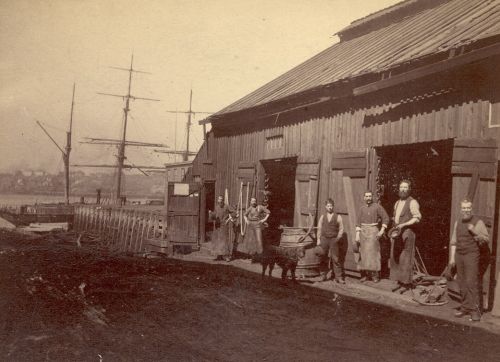

Small businesses flourished in the vibrant networks of towns and ports. In coastal cities like Boston, New York, and Charleston, merchants and shopkeepers dealt in both imported goods and locally produced items. Inland, general stores and taverns became focal points for economic and social life. These establishments provided goods, hosted meetings, and served as unofficial post offices and community centers.

The use of credit was essential to small businesses. Cash shortages meant that storekeepers extended credit to customers, often for months or years. This system created interdependence among neighbors but also deepened economic stratification. It was not uncommon for small entrepreneurs to fail due to bad debts or market fluctuations.3

Women also played significant roles in the small business economy, particularly in urban centers. Widows often continued their husbands’ businesses, and some women established their own enterprises as seamstresses, innkeepers, or midwives.4

Political Economy and Revolutionary Transformation

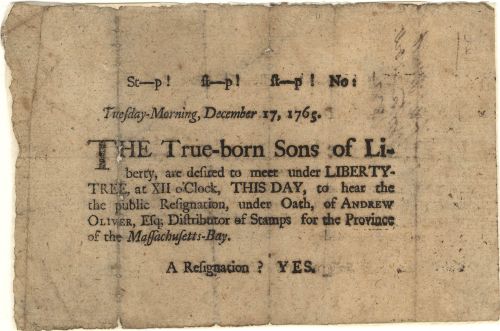

The American Revolution disrupted traditional economic structures but also created opportunities for small business growth. The war caused inflation, shortages, and shifts in trade patterns. Yet it also fostered a spirit of self-reliance and local production. Artisans and shopkeepers were at the forefront of boycotts and political activism. Groups like the Sons of Liberty often emerged from among tradespeople, who saw British economic control as a direct threat to their autonomy.5

The rhetoric of republican virtue and independence found resonance among small business owners, who linked their economic self-sufficiency with political liberty. After independence, these ideals influenced the economic philosophies of figures like Thomas Jefferson, who championed the small yeoman and artisan as the backbone of the republic.6

Small Business in the Early Republic

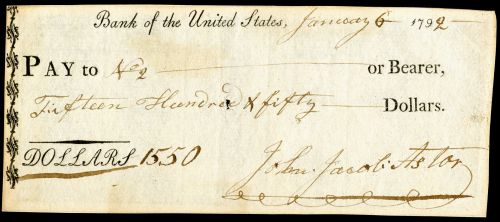

In the decades following independence, small businesses adapted to a rapidly changing economy. The Market Revolution of the early nineteenth century transformed transportation, communication, and production. While larger enterprises emerged, small businesses continued to dominate local economies, often incorporating new technologies such as the printing press or water-powered mills.

Print culture was particularly significant. Printers were typically small entrepreneurs who also served as editors, publishers, and postmasters. They played a vital role in shaping public opinion, circulating political ideas, and fostering a national identity.7

The rise of banks, turnpikes, and canals also impacted small businesses. Improved infrastructure enabled artisans and farmers to reach broader markets. However, this also increased competition and contributed to the growth of wage labor and capitalist enterprise models that sometimes displaced traditional small businesses.8

Continuity and Decline

Despite economic transformations, small businesses retained a strong presence in early American life well into the nineteenth century. They were resilient institutions, often passed down through generations. In many communities, local entrepreneurs were civic leaders, serving as justices of the peace, church wardens, or militia captains.

Yet the rise of industrial capitalism in the mid-1800s began to erode the independence of small proprietors. Factories, railroads, and corporate consolidation reshaped the economy in ways that marginalized the small artisan and merchant. Still, the cultural memory of early American small business—of the independent shoemaker, the family-run general store, the principled printer—continued to influence American ideals of work, freedom, and democracy.9

Conclusion

Small businesses in early America were more than economic units; they were institutions that shaped communities, politics, and national identity. Their adaptability, resilience, and centrality to daily life underscore the importance of examining them not just as economic actors, but as cultural and social forces. From colonial artisans to Revolutionary-era printers and post-independence shopkeepers, small business owners helped build the foundations of American society.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Gloria L. Main, Peoples of a Spacious Land: Families and Cultures in Colonial New England (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001), 87–90.

- Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, Good Wives: Image and Reality in the Lives of Women in Northern New England, 1650–1750 (New York: Vintage Books, 1982), 101–106.

- Cathy D. Matson, Merchants and Empire: Trading in Colonial New York (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998), 133–139.

- Ulrich, Good Wives, 132–137.

- T. H. Breen, The Marketplace of Revolution: How Consumer Politics Shaped American Independence (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 45–49.

- Richard L. Bushman, The Refinement of America: Persons, Houses, Cities (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1992), 287–290.

- Gary B. Nash, The Urban Crucible: The Northern Seaports and the Origins of the American Revolution (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1979), 312–317.

- Allan Kulikoff, From British Peasants to Colonial American Farmers (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), 211–214.

- Robert J. Gordon, The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The U.S. Standard of Living Since the Civil War (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016), 13–18.

Bibliography

- Breen, T. H. The Marketplace of Revolution: How Consumer Politics Shaped American Independence. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Bushman, Richard L. The Refinement of America: Persons, Houses, Cities. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

- Gordon, Robert J. The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The U.S. Standard of Living Since the Civil War. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016.

- Kulikoff, Allan. From British Peasants to Colonial American Farmers. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000.

- Main, Gloria L. Peoples of a Spacious Land: Families and Cultures in Colonial New England. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001.

- Matson, Cathy D. Merchants and Empire: Trading in Colonial New York. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

- Nash, Gary B. The Urban Crucible: The Northern Seaports and the Origins of the American Revolution. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1979. Ulrich, Laurel Thatcher. Good Wives: Image and Reality in the Lives of Women in Northern New England, 1650–1750. New York: Vintage Books, 1982.

Originally published by Brewminate, 05.22.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.