Across these three eras, the philosophy of consciousness unfolds not as a straight line, but as a shifting constellation of metaphors, anxieties, and aspirations.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Medieval Souls and Scholastic Shadows

To speak of consciousness in the medieval world is to enter a landscape shaped not by neurons but by souls. The very term consciousness, as it came to be articulated in later centuries, had no direct equivalent in Latin scholastic philosophy. Yet the questions it seeks to answer – of awareness, selfhood, interiority – were very much alive, though refracted through a theological prism.

At the heart of medieval consciousness was anima, the soul, conceived not merely as a metaphysical essence but as the animating principle of human life. Augustine’s deeply introspective writings, especially in the Confessions, laid groundwork for a form of interior exploration that could be seen as proto-phenomenological. He famously wrote, “I have become a question to myself”1, an early acknowledgment of reflexivity as a mode of inquiry. However, this introspection remained embedded within a theological framework. The purpose of self-knowledge was not to isolate the self, but to direct it toward God.

Scholastic thinkers such as Thomas Aquinas further systematized the soul’s faculties. Drawing from Aristotle, he categorized human awareness into vegetative, sensitive, and rational levels, positioning intellect and will as the highest expressions of consciousness. Yet even here, consciousness was not understood as autonomous self-awareness but as participation in divine rationality. The human soul, in perceiving itself, mirrored the divine intellect perceiving its own essence.2

Notably, the idea of synderesis, an innate habit of moral knowledge, introduced a subtle layer of pre-reflective consciousness, a kind of ethical awareness beneath rational deliberation. Though the term has faded from modern philosophy, its presence in scholastic discourse signals the medieval effort to account for internal moral experience. This was not the Cartesian cogito, but a sense of being watched not only by God, but also by the self in relation to God.

In this era, consciousness was not private. It was public in the deepest sense: a theater staged before the divine, with memory as witness and guilt as narrator. Dreams, visions, and temptations were not neurological ephemera. They were messages, sometimes diabolical, sometimes divine. One’s inner life, if spoken too boldly, could even become evidence in inquisitorial courts. To be conscious was to be accountable, in a metaphysical court that never adjourned.

Renaissance Mirrors and the Expansion of the Inner World

If the medieval soul dwelled in the shadow of the cross, the Renaissance self stood before a mirror. Here, a new curiosity bloomed: a fascination with individual interiority, human potential, and subjective perception. Still deeply religious, Renaissance thought nevertheless began to loosen the binding threads of purely theological anthropology.

The revival of classical texts, especially Platonic and Hermetic writings, encouraged a view of consciousness not only as a reflection of the divine, but as something that could ascend toward it. In Marsilio Ficino’s synthesis of Platonism and Christianity, the human soul was situated on a metaphysical ladder, poised between matter and spirit, capable of both descent and return.3 Consciousness became dynamic, aspirational rather than merely accountable.

Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and other figures of the High Renaissance also explored interiority through art and anatomy. The human body was dissected, both literally and symbolically, as a vessel of mystery. Consciousness in this period took on a spatial dimension: it could be mapped, traced, exposed. Alberti’s treatises on perspective and proportion served as metaphors for a new kind of seeing, one where the observer mattered as much as the observed.

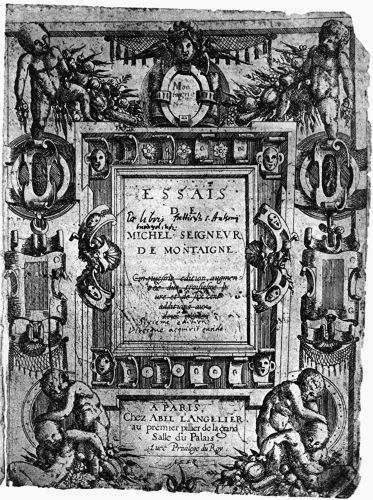

Yet this celebration of self-awareness was not devoid of anxiety. Montaigne’s Essays, often hailed as the birth of the modern self, reveal a consciousness in flux, riddled with doubt. “We are all patchwork,” he writes, questioning the coherence of the very self he so meticulously probes.4 His skepticism was not merely rhetorical. It reflected an emerging awareness that consciousness was not singular or stable, but layered, changing, even deceptive.

The Renaissance did not resolve the medieval question of soul versus self. It magnified it. The internal world became a space of exploration, but also of fragmentation. The old certainties of theological anthropology still loomed, but they no longer sufficed. Consciousness, in this interstitial moment, became both larger and less sure of itself.

Enlightenment Intellects and the Birth of the Modern Subject

Descartes and the Cogito’s Fracture

If the Renaissance held up a mirror to the self, the Enlightenment took a scalpel to it. With René Descartes’ declaration (cogito, ergo sum) a seismic shift occurred. Consciousness, now stripped of theological scaffolding, was recast as the foundation of certainty. The mind could doubt everything but its own act of thinking.5

Yet in Descartes’ formulation, this certainty was curiously abstract. The thinking self was disembodied, isolated, and cleansed of affect. His dualism severed the mind from the body, the soul from its world, setting the stage for modern debates that would echo through Freud, Husserl, and beyond. The Cartesian subject was both triumphant and tragic: it secured epistemological ground at the cost of exile from the sensual, historical, and communal.

The internal life, once governed by divine relation, became a self-sufficient ground for knowledge. This ushered in an age of unprecedented introspection, but also unprecedented alienation. What Descartes began, others would elaborate with both awe and dread.

Locke, Hume, and the Fragmented Self

John Locke’s theory of consciousness shifted attention from metaphysical certainty to empirical continuity. He defined personhood as a matter of memory: the capacity to identify with one’s past experiences.6 Yet in doing so, he introduced a delicate instability. If memory failed, did personhood collapse?

David Hume pushed this further, famously declaring that the self was nothing but a bundle of perceptions, connected by no underlying essence. In searching for a unified self, he could find only flickers and sensations, no hearth, no soul.7 Where the medievals found a stable metaphysical center, the empiricists discovered only process and flux.

This was both liberating and disquieting. Consciousness was now subject to analysis, but that analysis revealed no firm ground. The Enlightenment self was a chimera of impressions, not a being illuminated by grace. What began as an inquiry into rational identity became a confrontation with its absence.

Kant and the Synthetic Unity

Against this backdrop, Immanuel Kant attempted a grand synthesis. He affirmed that consciousness must have structure, that the self, though not empirically verifiable, was a necessary condition for experience. The transcendental unity of apperception was his solution: an a priori organizing principle, stitching together the manifold of sense into coherent experience.8

Kant did not recover the medieval soul, but he reintroduced the idea that consciousness had form, necessity, even dignity. In this view, the self was not discovered but constructed, actively weaving the fabric of reality through categories of understanding. This was not the divine mirror of Augustine nor the skeptical shrapnel of Hume, but a sovereign architecture built from within.

And yet even in Kant, there is a ghost of absence. The noumenal self, the thing-in-itself behind the phenomena, remains unknowable. Consciousness may be the light by which we see, but it cannot turn back upon itself without casting a shadow.

Conclusion: Toward a Historical Phenomenology of Mind

Across these three eras, the philosophy of consciousness unfolds not as a straight line, but as a shifting constellation of metaphors, anxieties, and aspirations. From the medieval soul anchored in divine gaze, through the Renaissance mirror of human potential, to the Enlightenment’s fractured and reformulated subject, each period reveals not only a different theory of mind but a different way of being human.

These transformations did not merely reflect philosophical developments. They mirrored changing cosmologies, institutions, and existential pressures. The rise of introspective theology, the rediscovery of classical texts, the impact of scientific method—all refracted through the lens of what it meant to know oneself.

What endures is the restlessness. Consciousness has never settled into a single form. It remains an open question posed by each age to itself. And perhaps that is its truest form: not a state, but a striving.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Augustine, Confessions, trans. Henry Chadwick (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991), Book X, §33.

- Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, I.79.3, trans. Fathers of the English Dominican Province (London: Burns Oates and Washbourne, 1920-1922).

- Marsilio Ficino, Platonic Theology, trans. Michael J. B. Allen and James Hankins (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001), Vol. I.

- Michel de Montaigne, Essays, trans. M.A. Screech (London: Penguin Classics, 2003), Book II, Chapter 1.

- René Descartes, Meditations on First Philosophy, trans. John Cottingham (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), Meditation II.

- John Locke, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, ed. Peter H. Nidditch (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1975), Book II, Chapter 27.

- David Hume, A Treatise of Human Nature, ed. L.A. Selby-Bigge (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1978), Book I, Part IV, Section VI.

- Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, trans. Paul Guyer and Allen W. Wood (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), A106–A110.

Bibliography

- Aquinas, Thomas. Summa Theologiae. Translated by the Fathers of the English Dominican Province. London: Burns Oates and Washbourne, 1920-1922.

- Augustine. Confessions. Translated by Henry Chadwick. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991.

- Descartes, René. Meditations on First Philosophy. Translated by John Cottingham. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- Ficino, Marsilio. Platonic Theology. Translated by Michael J. B. Allen and James Hankins. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001.

- Hume, David. A Treatise of Human Nature. Edited by L.A. Selby-Bigge. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1978.

- Kant, Immanuel. Critique of Pure Reason. Translated by Paul Guyer and Allen W. Wood. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Locke, John. An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. Edited by Peter H. Nidditch. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1975.

- Montaigne, Michel de. Essays. Translated by M.A. Screech. London: Penguin Classics, 2003.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.31.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.