Cigar makers used symbols of power to give all their cigar labels the air of exclusivity and privilege.

Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

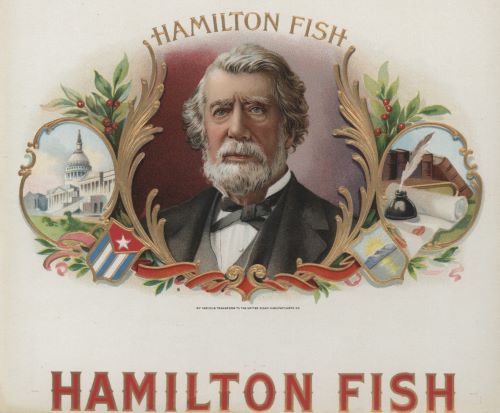

Hamilton Fish—that doesn’t sound like a great name for a cigar. But for the average smoker a century ago, the name was synonymous with power and position.

Four out of five men smoked cigars in turn-of-the-century America. The market was enormous, and cigar companies poured money into advertising. The prime method of publicity was the cigar packaging itself. Boxes of cigars lined up side-by-side at the tobacconist, vying for attention. Smoking was a decidedly masculine pursuit, and producers used every visual trick in the marketing book to catch a man’s attention—military heroes, scantily clad women, bright colors, and even ribald jokes. Heroic male role models abounded on cigar labels in the early 1900s. Hamilton Fish of New York, an 1840s Representative and later Senator and Secretary of State who oozed vigor, probity, pedigree, and honor, embodied all of the qualities of the target customer.

‘Uncle Joe’

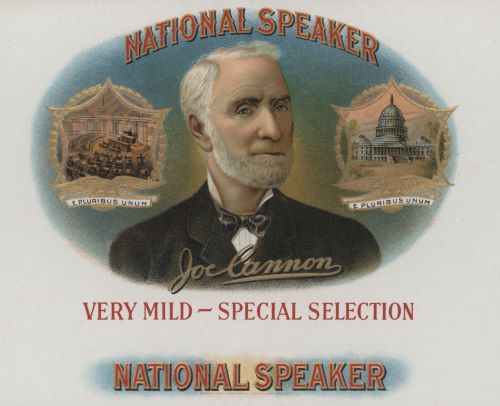

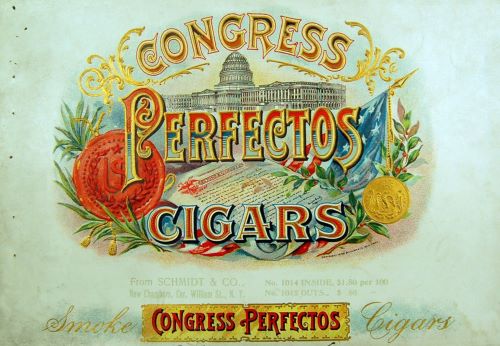

With hundreds of cigar companies and more than 20,000 registered brand names, the use of other congressional images was inevitable. Views of the Capitol showed up on several cigars, and Speaker “Uncle Joe” Cannon made a terrific cigar brand. Joseph Cannon of Illinois was an immensely famous Speaker of the House who loved publicity and issued folksy sayings while chewing a stogie.

Cigar makers used powerful men and symbols of power to give all their cigar labels the air of exclusivity and privilege. For example, Cannon’s hayseed personality joined with gavels, quill pens, laurel wreaths, and gold embossing to make him seem more dignified than his public persona.

Label It

The many printing companies that specialized in cigar packaging developed a standard style for the lithographs they made: laurels, medallions, crests, and fleurs-de-lis; a colorful center illustration with small vignettes on either side; the title in bold red or black, arched around the image; and glossy varnishing, embossing and debossing, and metallic inks double or even triple printed to maximize their luminosity. Lithographs were generally considered a form of art for the middle classes.

As technology improved and printing prices dropped, Americans began to collect labels like these for their scrapbooks, giving cigar companies even more advertising and ensuring the survival of these colorful bits of history.

Bibliography

- Grossman, John, Labeling America, Popular Culture on Cigar Box Labels (East Petersburg, PA: Fox Chapel Publishing, 2011)

- Rickards, Maurice, The Encyclopedia of Ephemera (London: Routledge, 2000).

Originally published by the Office of the Historian, United States House of Representatives, 07.10.2013, to the public domain.