The workings of marginalization had a direct impact on the uses of London’s spatial periphery.

By Dr. Charlotte Berry

Postdoctoral Research Assistant

Bath Spa University

Introduction

Underlying all forms of punishment in late medieval London was an understanding that those who had transgressed communal norms would and should be publicly recognized and known. The denunciation of offenders at the wardmote inquest or ritual penances before a Sunday congregation required by the church courts aimed both to warn the offender against further transgressions and to fix knowledge of their wrongdoing among neighbours. In the most extreme cases, a poor reputation could make it difficult for a Londoner to maintain a stable home, as they might face expulsion from their ward. This essay demonstrates how people engaged in the defence or rehabilitation of their reputations: in effect, how those who faced civic punishment or neighbourly approbation could reintegrate themselves into local society.

Central to the argument is that strategies of reintegration depended on the subtleties of social and spatial difference in the city. Gradations of social status determined how people mitigated or avoided loss of reputation. Spatial difference was also important to the defence of reputation: illicit rubbish-dumping and the running of brothels could be undertaken on the jurisdictional and geographic peripheries of London with less risk of punishment. The consequences of embarrassing moral transgressions such as illicit pregnancies and coerced marriages could be confined to religious houses and hospitals as a way to evade the local rumour mill. The workings of marginalization thus had a direct impact on the uses of London’s spatial periphery.

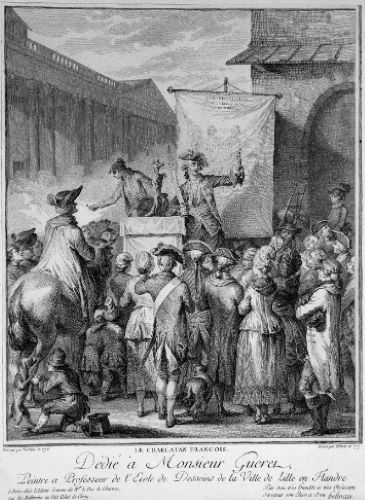

Gossip, ‘Fama’, and Marginality

In a largely oral society, gossip was an important means through which reputations were made; a person’s local fame (or fama, in the Latin of court records) was frequently used in court to substantiate or undermine them. Histories of mobility could be used in the consistory court to undermine parties or witnesses.1 Knowledge about past behaviour and character was spread through gossip, which, according to anthropologists, flourishes best in ‘close-knit, highly connected social networks’ with shared notions of proper behaviour.2 Gossip has been considered by sociologists as primarily a concern of those in the middle of the social hierarchy competing for social capital.3 However, Sandy Bardsley’s study of scolding accusations in late medieval England suggests that participation in speech that aimed to marginalize was widespread across the social hierarchy.4 Gossip needs to be understood in the broader context of late medieval cities, which were, as Christian Liddy argues, ‘surveillance societies, in which townspeople habitually watched each other and reported their activities for the benefit of government’.5 That reporting was horizontal, that is, among neighbours, as much as vertical: speech about, for example, sexual reputation was used to crystallize public opinion about those with a poor reputation which could then form the basis for further action.6 Within an area of dense population such as London and its region, the knowledge created by gossip would have circulated in small local areas rather than across the whole city.7 It was within the neighbourhood that character was best known and people could exploit local mechanisms of knowledge sharing and publicity to shame others or negotiate their own reputations.8 The formal mechanisms for exclusion and marginalization in London largely centred on local units such as the ward and the parish and relied on the knowledge that circulated within them to identify and punish offenders.

The importance of neighbourhood in developing and defending reputation was a key social continuity from the medieval to the early modern city, crucial as it is to Tim Reinke-Williams’s analysis of how women cultivated good reputation, and thus support networks, in the latter period.9 Participation in marginalization was itself part of the making of reputation in both late medieval and early modern communities.10 All Londoners were engaged in negotiating their own reputation through interactions with formal and informal authority. This is a theme that has recently been taken up by Ingram, who argued the importance of the late medieval wardmote and church courts in asserting the wishes of local householders keen to enforce moral standards.11 However, Ingram followed Frank Rexroth in viewing the wardmote as assigning a ‘persistent identity’ to malefactors, stating that ‘from such imposed identities, there was no escape’.12 Ingram’s focus on the instruments of sexual regulation tends, as this statement suggests, to downplay the extent to which individuals who stood accused of misdemeanours were also engaged in negotiating their reputation as much as any householder who accused them. As will be demonstrated, both ‘respectable’ householders and their poor neighbours participated in processes of marginalization and differences of status were important in how reputation was negotiated.

This essay is primarily concerned with those on the receiving end of surveillance and marginalizing speech. Marginality, as set out in the introduction to this book, was a state of jeopardy in which an individual’s accrued social capital was insufficient to prevent something bad happening to them. I have discussed many people in such situations, whether they were imprisoned, suffered local humiliation or became homeless. In stark contrast to Rexroth and Ingram’s characterization of such individuals as assigned persistent stigmatizing labels, Erik Spindler’s work on marginalization argued that ‘even in situations of marginality, individuals had agency’.13 For Spindler, those who were marginalized were able to draw on their own social networks to mitigate the effects of prosecution or punishment.14 Indeed, while many people did not possess social capital gained through participation in urban institutions and juries, they might, as Marjorie McIntosh suggests of women’s credit networks, have separate webs of connections through which they could draw social and economic resources.15 Those of low social status given the opportunity to bear witness in court might use this opportunity to enhance their own social capital and demonstrate their own good fame.16 Avoiding punishment could also involve the deployment of something closer to what Bourdieu termed cultural capital, in the form of knowledge about how to navigate and manipulate the requirements of the court.17 Decisions about marginalization rested on the negotiation of fama and, while it was a negotiation in which juries and trustworthy men undoubtedly held many of the cards, individuals were able to adapt their own behaviour and use their social capital to influence the outcome.18

This essay explores the possibilities and limits of strategy for those whose reputations were sullied by local gossip. In doing so, much of the discussion centres on defamation cases at the consistory court which shine a light on how reputations were made and broken. Defamation cases required some measure of legal fiction in their testimonies, since to be effective witnesses had to claim they no longer respected the plaintiff as a result of the defamatory words (which, if it were true, would have made them unlikely to be willing to bear witness). They needed to prove that a defendant had used certain actionable words that damaged the plaintiff’s local standing and shaped testimonies to fit the required legal narrative. Nonetheless, careful reading of depositions can yield significant insight into whose speech was cast as defamatory and whose as legitimate criticism of a neighbour.

The significance of the neighbourhood as the venue for making and disseminating fama highlights the connection between space and reputation in the urban environment. In the introduction to this book, we saw how medieval culture drew strong associations between the fringes of the city and physical and moral pollution. More than a rhetorical connection, there were also more nuanced understandings of space among urban dwellers which they might exploit in the defence of their reputations. Spatial agency – that is, the ability of people to produce and use space – is at the heart of geographers’ contributions to subaltern studies, an approach with great relevance here for its centring of those marginalized from urban society. The city margin is, according to Ananya Roy, a space in which there are multiple possibilities for adaptation and innovation by residents.19 This essay shares the approach of Roy and of historians such as Shannon McSheffrey and Tom Johnson, who have stressed the ability of medieval people to make astute use of urban space in navigating the legal system. As we shall see, there was considerable scope for the use of suburban space in negotiating reputation and evading fama.

Managing and Renegotiating Reputation

The business of negotiating reputation was a constant concern and intersected with the various methods of policing that prevailed in London. I now want to explicitly turn to how individuals went about this negotiation. They did so in the manner of their interaction with their neighbours and with the legal system and in their day-to-day conduct. How could people ensure they had a good reputation and, if their fama was poor, how did they attempt rehabilitation? The answer to both questions was highly dependent on status, both in terms of socio-economic position and aspects of personal identity.

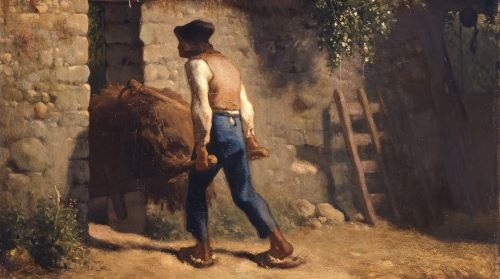

There were some for whom maintaining a good reputation was difficult because disorderly behaviour was to an extent expected of them. Immigrant aliens were frequently indicted at the wardmote for sexual misdemeanours, due to either a real association with the sex trade or xenophobic stereotypes. Another group who faced frequent wardmote indictments were those who operated alehouses and other venues for the sale and consumption of food and drink. About 9 per cent of all the surviving wardmote indictments were for huckstry of ale or beer or for selling ale contrary to the stipulations of the assize.20 As has been argued by Helen Carrel, food retailers were viewed with particular suspicion by civic authorities, who often identified them as disruptive and even morally corrupting influences, and alehouses were often ordered to close early during major festivals as a matter of public order.21 While, as Barbara Hanawalt argues, more substantial taverners and innkeepers who lodged guests were expected to police their guests’ behaviour, her work also shows a general fear among authorities of the disorder drinking houses encouraged and a mistrust of women inhabiting or running such establishments.22 Keepers of drinking establishments were held responsible for unruly behaviour in their houses and would have particularly feared presentation at the wardmote, their precarious position in relation to authority making them vulnerable to the spread of rumour and scandal, which could damage their business.23 Not only was food retailing itself considered morally suspicious, but also the acceptance of customers into the home could easily be construed as misgovernance of the household, given their mix of domestic and commercial space.24 The lines between drinking houses and illicit lodgings outside major inns could be blurred, and such businesses were liable to complaints at the wardmote. At this lower end of the scale, food and drink retailers were a group whose precarious position in society fits well within Erik Spindler’s definition of the marginalized.

In response, the food and drink retailers who appear within consistory court cases acted in ways which seem designed to mitigate the impact of their trade upon their reputations, particularly when their premises had been the settings for disorder. In 1510 Robert Gustard, a brewer of St Botolph Aldersgate, was said to have intervened to prevent one of the customers at his bowling alley angrily throwing a bowling ball at a priest’s head.25 In Robert’s own testimony about the incident, however, he was evasive: ‘as to the blow or violence specified in the article [of interrogation] he has nothing to depose’.26 It was wholly within Gustard’s interests to publicly downplay the violence of the dispute within his premises, as disorderly guests could have caused him an embarrassing wardmote indictment. Just the year before the fight at his own bowling alley, Gustard had been part of the Aldersgate wardmote jury which indicted one of his neighbours ‘for resorting of yll dyspossed pepull to hys howse and on Seint Stephens day laste passed ii suspessyowse persons lyke to make murder in her [sic] howse’.27 Gustard managed his reputation both in the heat of the moment by attempting to control the behaviour of his customers and in his deposition, where, in minimizing the violence of the incident, he perhaps sought to avoid creating further public fame about his establishment. This strategy appears to have worked for Gustard, as he continued to be selected for service on the wardmote jury, participating a total of four times in 1503–13.28 Gustard was probably running the kind of large establishment which Hanawalt saw as integrated into structures of policing, and his actions suggest he took his role as paterfamilias to his guests seriously and as such was careful to maintain his good reputation.

However, it was not just those with respected local positions as jurors who were concerned to defend their reputations. Another case suggests that rather humbler food and drink retailers tried to prevent the behaviour of disorderly customers from tarnishing the reputation of their establishments. Thomas and Katharine Atkynson, who appeared as deponents at the consistory in 1521, seem from many of the details of the case to have lived a somewhat precarious existence. It was Katharine Atkynson who, in the words of her deposition, ‘kepyd a vytylyng howse’ in the extramural parish of St Giles Cripplegate, while her husband was described as a wheelwright.29 This was a mixed household economy where the Atkynsons brought in income from a variety of sources to support themselves. Their ‘vytylyng howse’ – perhaps just a front room – was also apparently quite small, with neighbours in both chambers above and next door disturbed by a commotion within it.30 Evidently, this was not the kind of permanent establishment run by a male citizen who the civic authorities trusted to control their guests.31 The commotion in question was caused by a man called John Wright, who entered the house shouting, ‘how many hoorys [whores] have we here,’ before beating and stripping his wife, Elizabeth, who had come there to eat. The responses of the Atkynsons and their testimonies speak to a concern with their own reputations. Thomas Atkynson replied, ‘none withoute thow bryng hem [i.e. whores] with the’ to Wryght’s provocative statement and, when Thomas learned that Elizabeth was John’s wife, urged John to ‘take her and get the owt off my howse’.32 By rejecting Wryght’s description of his customers as whores and telling Wryght to take his abuse of his wife elsewhere, Thomas Atkynson perhaps sought to avoid a potentially damaging escalation of disorder in his home. In his conspicuous failure to intervene in John’s abuse of Elizabeth, Atkynson may also have sought to avoid suggestions that the Atkynsons had assisted Elizabeth in leaving her abusive husband, which could invite their own prosecution.33

John also challenged Thomas’s suitability to keep a house, saying, ‘yf thow were withowt thy howse as thow art withyn thow shuld never come withyn agayn’: that is, if he acted publicly as he did privately he would be expelled from the neighbourhood.34 This direct challenge to Thomas’s authority is very suggestive of how vulnerable poor victuallers such as the Atkynsons were to slanders against their reputation. Indeed, by the time the case came to the consistory, Thomas and Katharine had left the parish where their victualling house had been, St James Clerkenwell, moving to St Giles Cripplegate. There is nothing to explicitly link the case to their movement, but it can be imagined that this sort of incident, cast as misgovernment of the household, could have damaged their local reputation. Margaret Margetson, an alehouse keeper who acted as plaintiff in another case, was said to have ‘made expenses and labours in the prosecution’ of Ralph Trerise, who drunkenly claimed, ‘this howse is common for hors, theves and bawds’ when she threw him out for falling asleep before the fire.35 As one of Margaret’s witnesses sagely reflected, ‘such people good and evil, honest and dishonest are received in such a house’;36 alehouse keepers could not be too choosy about their customers, making them vulnerable to aspersions on their governance which even a sympathetic witness was cautious to portray as defamation. Margaret’s use of the consistory court to pursue Ralph is interesting, as it suggests the lengths to which she was prepared to go to defend the reputation of her business. The church courts were a useful venue for a plaintiff such as Margaret, whose defamer used tropes about alehouses that civic justice reinforced and whose rehabilitation thus relied on exoneration from another source. As we shall see, the potential for the church court cases to challenge judgements made elsewhere made them useful for those trying to redefine their poor local fama.

While Robert Gustard successfully defended the reputation of his brewhouse and retained his local position of influence, the examples of the Atkynsons and Margaret Margetson demonstrate the difficulties that food and drink retailers faced. It is likely that gender was an important factor here. Margaret Margetson and Katharine Atkynson were women held responsible for their customers despite dominant gender norms that defined proper governance as a masculine role. Women’s presence within the ‘permeable domestic space’ of the inn or tavern was problematic, implying ‘tainted womanhood’.37 Female retail of food and drink, particularly huckstery, was a persistent target of civic complaint.38 Households which retailed food and drink were thus at the nexus of anxieties about gender, governance, public order and moral standards, which forced their owners to work hard in the negotiation of their reputations, a struggle that was easily lost.

The definition of governance as a masculine activity meant that women who engaged in the kinds of informal policing which could bolster men’s status were vulnerable to having their actions cast as defamation.39 In 1520, a woman called Edith Stocker rushed to the defence of her husband’s and her employer’s reputations against the ill spoken of them by a neighbour. As reported by a deponent, she framed her criticism of her neighbour’s harsh words in terms of the prestige placed on residential stability, which was a common value in late medieval urban society. Edith reportedly told her husband that:

‘Roydon [her neighbour] hathe callyd the and Masterr Rowland knave and he hathe been her in this parishe 21 yeres’ referring to Rowland ‘and the tother haithe not been her 4 yeres’ referring to Roydon.40

Despite couching her criticism of him in terms of social norms, Roydon reacted aggressively, having overheard the conversation from his chamber above the Stockers’ house. He called Edith a whore and accused her husband of not being lawfully wed to her. The Stockers subsequently brought a case of defamation at the consistory court against Roydon to protect Edith’s reputation. One of their witnesses claimed that Edith’s husband took Roydon’s insult so seriously that he refused to share a bed with his wife for a week,41 though this seems likely to be a legal fiction calculated to stress the deleterious impact of Roydon’s words. The gendered nature of the abuse she received in return is typical of the defamatory language used against women, but in this context also challenged her right to pass judgement on a neighbour.

Even operating within the framework of accepted social conventions, women’s speech or attempts to curtail the behaviour of others could be unwelcome. In 1529, Elizabeth Philpott of the parish of St Sepulchre without Newgate found herself accused of defamation when she admonished her neighbour, William Stevenson, for not tackling local antisocial behaviour. She told Stevenson ‘he was as good as culpable because he allowed certain persons to keep bawdry so near to him’.42 Perhaps ill advisedly, she went on to add, ‘Mary, ther be curtiers [courtiers] and harlotts resorting to Raff Long house at unlawfull seasons of the nyght and about iiii of the clock in the morning the harlotts be conveyed away in spanyshe clokes’.43 It is not clear precisely why she felt Stevenson was responsible for policing Long’s behaviour: perhaps he was Long’s landlord or perhaps, being forty years old and having been resident in the parish for six years, Stevenson was the kind of local man expected to take a role in formal and informal policing of the neighbourhood. In any case, an accusation that could well have formed the basis of a wardmote indictment when made by a man instead resulted in Elizabeth being accused at the consistory court of defamation by the alleged bawd Ralph Long. The problematization of women’s speech in a legal context was not new. In the fourteenth century, women were increasingly excluded from raising the hue and cry about crimes at the same time as a discourse of scolding, which problematized women’s voices in legal and social contexts, was on the rise.44 Defamation accusations such as scolding could be a response to women’s attempts to engage in processes of marginalization that were considered more properly conducted by men. While men accrued social capital from institutional participation, female social capital was gained through sociability and reciprocity.45 As a result, even women considered reliable could find that their standing did not translate easily into the arena of community regulation.

However, it is possible that the alternative venues in which women gained their social capital also insulated them to a degree from the consequences of institutional marginalization. Women who had faced official censure for their behaviour could still maintain local female friendships. For instance, Margaret Thompson was a witness to a 1530 defamation case in the parish of St Anne and St Agnes against whom the defendant brought a counter-witness. The counter-witness was Thomas Adyson, a man who served on the Aldersgate wardmote jury seven times from 1514 onwards. He testified that Margaret had committed adultery in George and Agnes Browne’s house in the previous year, for which she had been imprisoned in the counter by order of the alderman of Aldersgate.46 The circumstances of the case in which Thompson was a witness, however, suggest she was not marginalized from female social networks in the parish. At three o’clock in the afternoon she had been chatting in the doorway of the Browne’s house together with Agnes Browne, the wife of Dean, the goldsmith, and ‘a number of others living in that place’ when they all witnessed a quarrel on the other side of the street.47 This case suggests that a woman such as Margaret Thompson, who had been not just publicly indicted but also punished by institutional structures, might still have a social network among the women of her neighbourhood. Women fleeing violent relationships employed their social resources in a range of ways both to evade the social networks of their husbands and to build themselves new lives. Although the social lives of women in late medieval London are hard to reconstruct, less intertwined as they were with the formal and thus recorded world of institutions and office-holding, it seems that their social capital might not always have been destroyed by formal mechanisms of marginalization. This is an important reminder that we cannot always read formal indictments of individuals as proof that they were totally ostracized from their communities; there would have been multiple social groups within a neighbourhood with their own dynamics of inclusion and exclusion.

For those male householders who held local office and expected to be able to exert some informal power, the management of reputation could involve a skilful negotiation of the line between defence of one’s own character and defamation of another. We have encountered Roger Newesse, who was evasive when, in 1523, he objected to the selection of Roger Wryght to the wardmote of Farringdon Within, saying that there was ‘a pad in the straw’ (a toad in the haystack, that is, an unknown danger) which disqualified Wryght.48 Newesse’s subsequent refusal to clarify his statement or make any more specific accusation was probably motivated by the desire to avoid becoming accused of defamation himself. When confronted at his house by Wryght and the alderman, Newesse was alleged to have said, ‘I sayde soo or as ylle and ye may saye that I am a good fellowe for I sayd no thing be hynde your backe but I saye yt to your face.’49 His careful avoidance of any specific accusation while at the same time bragging of his honest dealings in the matter, can be interpreted as a targeted attempt to lower Wryght’s status without any damage to himself. Although judgement of others was a way for men to demonstrate their authority and status, when directly confronted with a threat a wise strategy was to avoid direct criticism of others’ behaviour. Tom Johnson has argued that consistory court depositions show witnesses both employing social discourses and moulding them to fit what the court required. This was both in the crafting of depositions and in their own actions leading up to a case, which might be engineered with an eye to building a successful court case.50 The ability to ‘pre-construct’ testimony, and to know the line between defamation and legitimate exercise of authority, would have been learned through participation in legal processes as jurors and witnesses. It was thus a resource that, arguably, was more available to those wealthier people who most commonly occupied such positions. We can perhaps get a sense of this balancing act in the words of Marion Chylderly, who, when accused of being a leper by her neighbour Agnes Wylkyns in 1523, allegedly replied:

‘that there was never good woman that callyd me soo’. To which Wylkyns said ‘Callyst thow me harlott’, Chylderley replying ‘nay, as trewe ys the oone as the other’.51

Whether this is what Chylderly really said, or a later construction by her witnesses to avoid a countersuit, it suggests an awareness and a clever avoidance of actionable words. Crafting plausible legal stories in the church courts and having access to the witnesses who provided plausibility were important elements of the social and cultural capital that householders could bring to bear in maintaining their reputation and authority.

In this context, vocalizing judgement of others when one’s position exercising informal power was not assured could be a reputationally risky activity, as Guy Dobyns of St Botolph Aldgate found. He appears to have launched a campaign against his neighbour Elizabeth Goodfeld to damage her local fame. He claimed, among other accusations, that she had acted as a bawd between a gentleman and a tailor’s wife, she accepted sex as repayment for debts and that she had conceived a child with a priest.52 Dobyns made these accusations to the Portsoken wardmote jury sitting at the Three Kings inn in June 1510 and again before the alderman, the prior of Holy Trinity Aldgate, in July. He claimed as proof that when her husband was a wardmote juror he had signed an indictment against her. Guy Dobyns apparently failed in these attempts: the wardmote jury refused to indict Elizabeth, which presumably explains why he took his complaints to the alderman directly, and by December he himself was a defendant in the consistory court, accused of defamation.53 The case suggests the risks associated with calling out others’ behaviour when, even as a man, you were not apparently considered of sufficient authority to do so. It also suggests some of the legal skill and knowledge required in demonstrating one’s own authority. Although jurors probably had specific incidents in mind when they indicted individuals which the general terms of wardmote indictments disguise, Dobyns was not a member of the jury and, in appearing before them and the alderman with such specific accusations, he seems to have miscalculated. Two long-standing wardmote jurors appeared against him in the consistory defamation case, serving to distinguish between their legitimate authority, in the words of one, ‘to inquire as to diverse gross excesses and those men and priests suspected of ill rule’ and Dobyns’s illegitimate attempt to marginalize a neighbour.54 For Dobyns, his inability to convince the jury and marshal persuasive witnesses for his own case suggests lesser social resources, and thus the importance of both social networks and legal knowledge to negotiating reputation. In a society where so much community management was done informally, it was important for the institutional basis of judgement to be reaffirmed in a case such as this, avoiding the possibility that the wardmote could itself be associated with defamation. For Dobyns, what could have been an attempt to gain respect among his neighbours for his exposure of Elizabeth’s alleged behaviour probably damaged his reputation, given the jurors’ depositions against him.

As these examples suggest, the pressures of managing reputation worked horizontally as well as vertically; that is, householders who aspired to authority still had to negotiate their right to exert it through management of their own reputations. Ian Forrest’s close examination of who made up local elites notes that fortunes could rise and fall and, even where they were of equal socio-economic status, men needed to prove themselves to other local trustworthy men before taking on the role.55 Reputationally, the high dropout rates for wardmote jurors and the need to take up defamation cases suggests that such status was mutable and contested rather than there being a fixed social centre of neighbourhood life. The shaming of neighbours was not just used to exert pressure downwards on the poor but also to shape and reshape the pecking order among the relative elite.

However, while all might have faced the pressure to maintain or defend their reputation, the means by which they did so varied. We have already seen that food and drink retailers who were likely to receive short shrift in civic courts might turn to the consistory court instead to defend their reputations. Roger Wright (the ‘pad in the straw’) aspired to be a wardmote juror himself and, according to one witness, was ‘vexed by many expenses in this case’ to restore his wife’s lost reputation.56 But for those without the cash for such expenses and without the expectation of gaining a respected position as an officeholder through a renegotiated reputation, there were other options. Richard Trussyngton, a waterman (plier of small taxi boats on the Thames) of the parish of St Michael Queenhithe, appeared as a deponent in a defamation suit in 1523.57 The plaintiff called several opposing witnesses who said Trussyngton was not a trustworthy character: that he was a pauper who got into drunken brawls, provoked arguments among his neighbours and was likely to have been paid for his deposition.58 Unsurprisingly, he had come to the attention of the wardmote inquest and had, according to the counter-witnesses (two of whom were wardmote jurors), been indicted seven years in a row as a quarrelsome man and once for failing to chasten his scolding wife.59 One of the counter-witnesses gave an insight into why Trussyngton could be indicted so many times without being expelled from the ward: Trussyngton had found people to provide surety to the alderman that he would keep better rule in future.60 That he could find sureties for his behaviour suggests that, despite the repeated judgements against him, he had not lost all local credit and may indeed have endeavoured by better behaviour to regain reputation. Yet, as demonstrated by the attitude of the counter-witness against him, the admission of guilt involved in such a process was nonetheless considered deeply damaging by those who aspired to exercise authority themselves. For those such as Trussyngton without the means to defend themselves through defamation suits, showing deference to the authorities of the ward and contrition through use of sureties was enough to protect themselves against expulsion. Similarly, in the church courts, the lower commissary court offered those indicted the option of compurgation, which allowed the accused to present a certain number of sureties who declared their innocence. While this may have made church courts ineffective as a deterrent against misdemeanours in an urban environment where witnesses were easy to come by,61 from the perspective of poorer Londoners it allowed them to avoid either the expense of pursuing accusers through defamation suits in the consistory court or the shame of excommunication. Martin Ingram contrasted the harsh, arbitrary nature of civic justice with the reintegration offered by church courts.62 In fact, both systems allowed leeway for those without great financial resources to avoid harsh punishment or legal expense so long as they showed deference and had enough friends to vouch for them.

In the ecclesiastical legal system, the higher and lower courts dealt with offenders of differing status. As a result, different neighbourhoods tended to send cases to different courts. In Ingram’s analysis of over a thousand late fifteenth-century commissary records, the most common parishes of origin for cases were nearly all extramural: St Botolph Aldgate, St Botolph Bishopsgate, St Mary Matfelon, St Botolph Aldersgate, St Bride and St Sepulchre.63 In 1515, 13 per cent of all commissary cases with a recorded outcome were generated from St Botolph Aldgate alone.64 As discussed, the commissary court largely heard cases on the accusations of neighbours, some of which were brought after wardmote indictments, and the accused could evade punishment by finding compurgators who swore that the accusations were not true. The situation at the higher consistory court – which heard personal suits – was very different. Even with careful selection it was possible to find only seventeen consistory suits that originated in St Botolph Aldgate, St Botolph Aldersgate and St Botolph Bishopsgate combined in the deposition books surviving from 1467 to 1533.65 This pattern makes sense if we understand the consistory court as a venue in which the better-off could launch civil suits to defend their reputations against those who had specifically defamed them, often (but not always) their householding neighbours. In extramural neighbourhoods where the wealthy constituted a smaller portion of the population, the consistory simply had less of a constituency of potential users. The poorer population of extramural neighbourhoods was more likely to be indicted to the lower commissary court or wardmote for bad behaviour and to accept its authority by submitting themselves to compurgation or finding sureties. In doing so, they might affirm social ties with those who were willing to vouch for them. This was probably enough to rehabilitate their reputations among their peers, negating the need to dispute the accusations and launch a counter-suit for defamation in the consistory. As a result, the occasions where the extramural poor felt the need to defend themselves with suits in the consistory were comparatively rare. An unusual example was that of alleged prostitute Agnes Cockerel, and it seems that her case was unlikely to succeed, given that her neighbours in St Sepulchre without Newgate were apparently certain of her poor reputation.66 Rehabilitation probably meant different things to different Londoners and the church courts performed different functions for different sections of the community, enabling rehabilitation in different ways.

For the poor, formal mechanisms of marginalization impacted upon their reputation in complex ways that were different to those aspiring to local authority. When called as deponents, respectable men could be lined up as counter-witnesses against them to attest to their low status and unreliability, using wardmote appearances as evidence. Yet the poor were still called on by neighbours to bear witness. Sometimes other aspects of their status, such as great age, might lead to a reliance on their opinion and memory in local disputes: it is hard to imagine that William Fryday, an alleged ninety-year-old who had dug graves for a living, was anything other than poor, and yet his testimony in a parish boundary dispute went undisputed.67 The value of memory in court meant that great age could overcome what were otherwise legal disabilities, such as gender and poverty.68 Deponents sometimes tried to distinguish between the general unreliability of the poor as witnesses and the character of individual paupers: several times, counter-witnesses used some combination of the words ‘honest pauper’ or ‘poor yet honest’ to describe others.69 James Lovan in 1524 deposed that ‘John Broke is an honest person yet he is poor and has few goods of his own.’70 The rhetoric of honesty despite poverty, also common in the early modern church courts, reinforced the assumed co-dependence of morality and social status.71 Yet such statements also hint at the limitations of deposition evidence for assessing social relations between the economically marginalized and their better-off neighbours: legalistic categories of who was and was not fit to depose might map unevenly on to social assessments of individuals. Deponents made their own judgements about who of their neighbours could be relied upon as a witness, even if others called them paupers.72 Given their assumed dishonesty, the best defence of reputation for the poor was perhaps to stay out of trouble, as far as possible. As we have seen in a number of cases, formal judgements against the poor may not have resulted in them being cut off from local social networks. The mobility of the poor perhaps made it possible to maintain a support network around London’s suburbs and liberties. Negotiation of reputation may have been far more about staying out of trouble as much as possible and reinforcing friendships which could turn into sureties when faced with legal indictments.

Those aspiring to local prominence played a different game with its own risks, where demonstration of authority was both a key marker of success and a potentially defamatory activity. Because these middling individuals relied on those with local authority for their social networks, finding oneself on the wrong end of a wardmote indictment required a robust defence which the consistory could provide. Legal knowledge and access to respectable witnesses were thus social resources that were very useful in the negotiation of respectability and marginality; the middling sort could more easily defend themselves through both a good understanding of how to ‘pre-construct’ testimony and their social networks, which contained men and women who might be thought reliable witnesses.

In general, those who lived in marginal neighbourhoods had less access to such social resources; authorities here instead expected the poor to rely on one another for support, which they had to do in order to mitigate the impact of wardmote or commissary court indictments. There were also alternative forms of authority on the margins of the city in the form of liberties and religious houses, as well as a jurisdictional complexity that could allow people to evade punishment. This is the point where geographic and social marginality overlapped – not because people were simply pushed to the fringes but because, in marginal spaces, the poor could attempt to defend or renegotiate their reputations. Space was, as the following section shows, a resource which all used in attempting to manage their reputations.

Navigating Justice at the Margins

Negotiating reputation could mean instrumentalizing spatial as well as legal knowledge of London. It is salient at this point to return to the nuanced spatial and jurisdictional arrangements of extramural neighbourhoods. The presence of religious houses with growing lay communities and legal privileges for their populations, the division of extramural parishes by the city’s line of jurisdiction and the less intensive development of land combined to create a distinctive extramural environment. This was underlined by ceremonial uses of civic space, which prioritized the city within the walls as a site of pageantry, and even by the symbolic ‘othering’ of London beyond the walls as a criminal space by civic proclamations.73 Prostitution and the convalescence of the sick were activities which seemed to gravitate outside the city walls sometimes with tacit civic approval.74 The concept of the ‘zone of exception’, developed by geographer Ananya Roy, has been used to compare ethnic quarters and religious precincts in medieval cities to modern gated communities and private developments which spatialize urban citizenship, often to the exclusion of particular groups, enabling some behaviours prohibited in the surrounding city while prohibiting others.75 Recent readings of the concept of sanctuary and jurisdictional privilege in medieval English cities have stressed that people were adept at navigating spatial complexity; the multiplicity of medieval urban jurisdictions was part of a dynamic process whereby individuals and competing authorities negotiated social relationships.76 Boundaries of sanctuary space were determined ‘through social practice, its observation and its recognition’.77 Londoners with an understanding of the legal topography of the city, and of its ‘zones of exceptions’, could thus instrumentalize that knowledge in the defence of their reputations. The fringes of the city afforded opportunities for individuals to escape their reputation and avoid public fame. Consistory court depositions give an insight into how they did that, as well as the way legal processes could themselves be influenced by the utilization of spatial and jurisdictional difference.

Control of behaviour in London depended on close observation, with wards increasingly divided into tiny precincts as population density increased.78 However, the open character of extramural neighbourhoods and the presence of ‘zones of exception’ undermined neighbourly watchfulness. The complex consistory cases of Elizabeth Brown and Marion Lauson c. Lawrence Gilis featured an impressive array of disreputable witnesses and revolved around two competing marriage suits. One of the contracts was made within the city centre parish of St Andrew Undershaft and the other in St Botolph Aldgate. The contract made in St Andrew’s between Gilis and Lauson bore the hallmarks of legitimate marriages outlined by Shannon McSheffrey; statements of present consent were made in the hall of Lauson’s house and were repeated at a neighbour’s, witnessed by many, including the parish chaplain, who advised on the proper words of consent.79 By contrast, the Aldgate contract with Brown took place in the house of a man described as a ‘beermaker’, so probably a drinking establishment, with just two witnesses. These were William Alston and John Waldron, men whose disreputable characters, association with Stewside brothels and mobile lives have already been noted.80 The easy mobility of these men and their ilk between the precinct space of their home at St Katharine’s, with its port-side character and reputation for licentiousness, and St Botolph Aldgate affected the character of the latter. The ward of Portsoken, which was largely coterminous with St Botolph Aldgate, produced numerous indictments for sexual misdemeanours and soliciting heard at the commissary court.81 The boundaries of jurisdiction were freely crossed by the everyday mobility of Londoners. ‘Zones of exception’ and the deviant behaviour and morality which characterized them, could spill over into areas within the jurisdiction of the city. Laurence Gilis perhaps felt confident of being able to easily break a promise of marriage made in an alehouse outside Aldgate in favour of what was probably a more advantageous match with an ‘honest’ woman, probably a widow of means, since Marion Lauson had her own house. Through its border with St Katharine’s precinct, the neighbourhood outside Aldgate was something of a grey area into which undesirable elements of urban society could drift and within which Londoners from the intramural city might expect their actions to have fewer consequences. The twist in the tale is that Laurence Gilis and Marion Lauson solemnized their marriage, contrary to the injunction of the consistory, in the hospital of St Giles in the Fields, thereby utilizing an extramural religious house to evade sanction.82 This use of religious precincts to avoid scrutiny is a theme to which will be returned to later in this essay.

Within the precinct of St Katharine’s itself, the highly mobile maritime community could evade neighbourly oversight and social responsibilities. The case of Sutton c. Jervys, regarding a disputed marriage contract made at St Katharine’s in May 1521, suggests how the unsettled lives of the sailors who lodged there, taking advantage of its proximity to the river, created a community where standards of behaviour might be difficult to enforce. There were only two witnesses to the alleged contract who appeared in the consistory, both the wives of mariners who lived at St Katharine’s.83 Although three men were also said to have been present for the contract, unusually for a marriage case, none appeared as deponents, perhaps because they were sailors not in London at the time the case was heard. The alleged groom (John Jervys) was said to have lived at Rotherhithe at the time of the contract and Stepney at the time of the depositions, places abutting the river’s north and south banks to the east of St Katharine’s. Such an unsettled living arrangement was shared by a mariner deponent in another case, said to be ‘living about the city of London, not having a particular house, staying at St. Katharine’s by the Tower’, a situation perhaps similar to that of John Jervys.84 The highly mobile community of mariners living in St Katharine’s precinct but moving easily around its neighbouring areas did not conform at all to the ideal model of the stable household. Men here could easily evade responsibilities, and wives who remained on land might be the mainstay of the neighbourhood community.

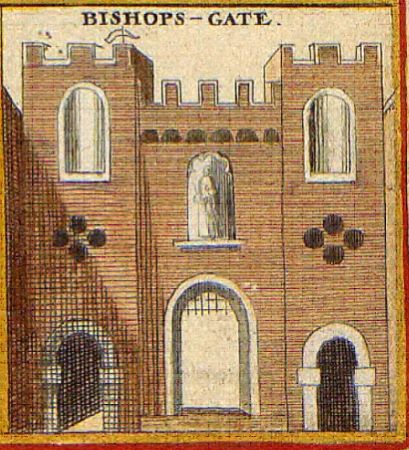

Precincts could support those whose lives did not fit the urban social ideal. The classic example of this is their association with prostitution, and here the ability of local communities to shape legal indictments was probably a factor. At Norton Folgate, the liberty outside Bishopsgate, a woman named Alice Pounfreyt was indicted every year from 1449 to 1464 as a prostitute and keeper of prostitutes.85 Although she was regularly fined forty shillings and once, in 1462, asked to expel specific prostitutes named Agnes and Emmota from her property,86 she was never herself expelled or asked to leave, as other prostitutes and maintainers of malefactors were. She was the widow of long-standing local resident Thomas Pounfreyt and seems to have inherited from him the freehold of her property.87 As a well-established resident of Norton Folgate who presumably had many friends and acquaintances among her neighbours, Pounfreyt seems to have been tolerated and fined, admittedly at quite a high level, rather than driven from the neighbourhood. Repeated fines as a kind of licensing system were a common manner of handling prostitution in many of the liberties surrounding London.88 The status of precincts as ‘zones of exception’ enabled the determination and enforcement of communal standards which could be at odds with civic and broader social ideals.

The creation of precincts by their residents as spaces in which otherwise frowned-upon activity might be tolerated apparently influenced the manner in which they were understood and used by otherwise ‘respectable’ Londoners seeking to hide activity which might pose a risk to their reputation. In July 1529, Henry Fyt of St Mary Staining, Aldersgate ward, deposed how two years before his neighbour William Bowser had an adulterous affair with servant Joan Stere, resulting in a pregnancy. Joan was sent to the hospital of St Mary without Bishopsgate to give birth. Her baby son was baptised there and subsequently the boy was raised at Bowser’s expense in the village of Havering-atte-Bower in Essex.89 By the time of the case, Joan lived with a widow in Carter Lane in Castle Baynard ward, where Bowser maintained and continued to visit her.90 Bowser appears to have arranged the affair and its fallout such that it was kept at a distance from the space of the parish. Both Joan and her child were maintained outside the neighbourhood. Although the ward of Castle Baynard had complained about Joan Stere’s adultery and expelled her,91 Bowser himself avoided consequences and continued to serve on the Aldersgate wardmote jury,92 suggesting a (depressing) degree of success in his strategy.

Other kinds of activities that could pose a reputational risk within the parish instead took place in the precincts of religious houses. In the following examples, Londoners exploited discourses of urban space in the handling of circumstances around marriage and separation. When the draper Thomas Dudley, a long-standing resident of St Michael Cornhill, discovered in 1525 that his servant Anne Trym was pregnant by his apprentice John Sandock, Dudley took the pair to the conventual church of Austin Friars. While there, he and his neighbour Thomas Knyght pressured John and Anne to contract marriage, and they returned to Dudley’s house to exchange the proper promises, witnessed only by Knyght, Dudley and Dudley’s wife.93 In this example, it is notable that the frank discussions leading up to the marriage were sited within the Austin Friars, while the contract that made the marriage binding was still witnessed in its proper location in the hall of Dudley’s house.94 A contrasting example is provided by the contract of Agnes Wellys and William Rote, which took place under threat of violence in Agnes’ father, John Wellys’, house; John Wellys drew his knife to threaten Rote, and Rote attempted to escape, instead being returned to the house after Agnes and her mother cried, ‘keep the thief!’ to passers-by.95

It was perhaps to avoid these kinds of dramatic scenes, which could invalidate a marriage by implying coercion, that Thomas Dudley used Austin Friars as a space in which to ensure compliance, using an understanding of the legal requirements about a valid marriage and of urban space. In the friary church, he ‘reproached or chastised’ John Sandock, who, ‘because of fear of being incarcerated by Thomas Knyght’ and ‘the course of his apprenticeship not expiring for three years … submitted himself to the discipline and arbitration’ of Dudley and Knyght.96 Of course, Sandock’s testimony was shaped to emphasize his lack of consent. Nonetheless, Dudley and Knyght broadly corroborated his version of events, stating that Austin Friars was the location in which Sandock ‘confessed … that Anne was impregnated and the time and place when he committed the offence’.97 Disciplining Sandock at Austin Friars and ensuring his compliance in advance of the contract avoided the chaotic scenes described in Wellys c. Rote. It also may have been intended to secure the contract against subsequent challenge. By ensuring the proper creation of a marriage contract within its legitimate space, the hall of the master’s house, while keeping discussions that revealed the illegitimate origins of the marriage in a ‘zone of exception’ such as Austin Friars, Thomas Dudley probably hoped to keep his lapse of governance quiet. In Wellys c. Rote, by contrast, the conjunction of the threats to Rote and the contract itself within the household resulted in witnesses who could attest to the full, embarrassing circumstances. Wellys’ witnesses Robert Ryngbell and Richard Hadley were called to the house at three in the afternoon to witness the contract, apparently after the incident where Wellys drew a knife, which happened during a meal.98 The failure of patriarchal control suggested by Anne Trym’s pregnancy was spatially disassociated from both the marriage and the Dudley household, which both minimized the risk to Dudley’s reputation and upheld the legitimacy of the contract. Austin Friars, at a few parishes’ distance from St Michael Cornhill, was perhaps considered just far enough away to be discreet. Once again, the management of events surrounding a case involved the careful use of urban space, separating conventional and disorderly activities into appropriate spaces.

The exceptional space of a religious precinct could also be used in the unmaking of a marriage. While divorce in the modern sense was not possible under canon law, couples could obtain a legal separation from ‘bed and board’ (although not the freedom to remarry) if they could prove that their spouse was excessively cruel or violent.99 Victims of domestic abuse might move around the city, hoping to escape the attentions of their spouse. In a suit for separation from the consistory court in 1532, the extramural hospital of St Bartholomew and its resident clergy seem to have played an important role in the legal strategy of the couple. The suit was brought by John Hawkyns against his wife, Elizabeth, who lived near Red Cross Street outside Aldersgate. John’s deponents related incidents where Elizabeth had told her husband, ‘if I can not be divorced of yow I will be the cause of your dethe’, both at their house and within the hospital of St Bartholomew.100 Both of these witnesses lived in the hospital: one was Henry Manocke, described as a servant of ‘Master Barley, chaplain of our Lord King’, and the other was Thomas Carter.101 Elizabeth’s alleged threats of violence if a separation could not be procured were made both in the hall of the hospital and within the Hawkyns’s own house, where both deponents said they had been invited. The circumstances suggest that Elizabeth, perhaps with the cooperation of her husband, engineered the context of her threat to give it legal force in procuring a separation. As R. H. Helmholz noted, canon law required concrete evidence of violence rather than simple threats, and other separation cases often include detailed descriptions of public violence witnessed by neighbours.102 By contrast, Thomas Carter simply deposed that Elizabeth Hawkyns made her threat with ‘a mischievous mind’, but no weapon or assault was mentioned.103 Instead of acts of reputationally damaging public violence, the Hawkyns’s separation case relied upon the residents and space of a hospital precinct in order to procure reliable witnesses.

In this instance, the precinct stood as an alternative space to the neighbourhood; rather than relying on the creation of local scandal to justify the annulment, Hawkyns c. Hawkyns involved hospital spaces in a manner that was presumably less hazardous to reputation. While the testimonies in other separation cases were recollections by neighbours of the disorderly lives of a couple, the deponents in the Hawkyns’s case were, notably, outsiders to their parish. Thereby the Hawkynses made their case for a separation without having created a disorderly local fame. The rehearsal of Elizabeth’s threat to John before the same witnesses in a semi-private household space and in the ‘exceptional’ space of the hospital seems part of a performance made in anticipation of a consistory case. Such a performance is analogous to marriage cases, where vows were made and marriage tokens shown to multiple witnesses as part of a conscious demonstration of the legitimacy of the contract.104 Although we ought to be cautious in ascribing such performance to all cases, particularly given the creation of narrative at work in retrospective testimony, here it is justified by the remarkably careful use of urban space and choice of witnesses.

However, while it sometimes suited Londoners to use the exceptional space of the precinct to bypass the court of neighbourhood opinion, their exceptional status was by no means unchallenged. Wardmotes could be used to challenge liberties. In the early sixteenth century, the wardmote jury of Aldersgate targeted residents of St Martin le Grand.105 In the context of ongoing hostility between the city and St Martin’s, this presentment offers a local perspective on the dispute, in which the infringement of the city’s jurisdiction was expressed not in terms of legal principle but through recitation of the individual sanctuary dwellers who were known in the neighbourhood.106 It is quite striking, considering the importance of the boundaries dividing sanctuary, that not only household heads but also servants could be named by the Aldersgate jurors.107 This further emphasizes how networks of social knowledge did not respect jurisdictional boundaries in areas containing exempt precincts. Indeed, this sense of neighbourhood across the boundaries may explain why such presentments were made; rather than being isolated and external, those in other jurisdictions were the neighbours of Londoners who lacked their privileged status. Therefore, the presence of a sanctuary and liberty meant far more than an abstract legal division between Londoners and privileged liberty-dwellers. It was instead an active source of division within local communities and, as Gervase Rosser argued of similar disputes in Hereford, articulation of complaints appealed to the notion that the urban community ought to be a unified whole.108 At Norton Folgate, the manor’s chief pledges consistently complained of Bishopsgate innkeepers and a gongfarmer (who cleared privies and cesspits for a living) dumping their refuse within the boundaries of the precinct. They knew these men by name because they were their neighbours but could do little to prevent them exploiting Norton Folgate’s status.109

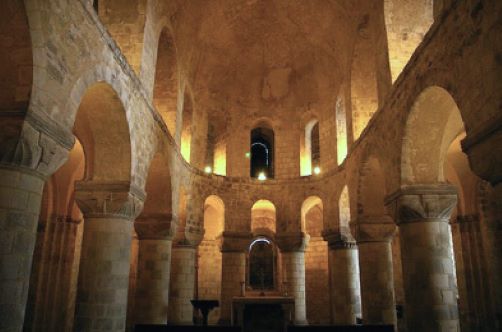

How could it be possible that precincts could act simultaneously as social space contiguous with the surrounding neighbourhood and as zones of exception providing venues for activity that could escape wider lay notice? These dual uses produced unresolvable tensions inherent in the complex jurisdictional landscape of London and shared in common with many English towns.110 There are three principal reasons why these tensions developed on the margins of London and why such dual uses could coexist. First, the precincts of religious houses and hospitals maintained a range of spaces which we have seen being used in the examples in this essay in different ways. The church within the Austin Friars where John Sandock and Anne Trym confessed to fornication or the hall of the hospital of St Bartholomew where Elizabeth Hawkyns threatened to kill her husband were very likely spaces to which the laity had only controlled access and from which, we can therefore assume, it was harder for fama to develop. However, the development of extensive lay housing within precincts in the later fifteenth century must have had a considerable impact on the accessibility of outer precinct space to the laity and contact with the wider neighbourhood.111 The extremely crowded nature of the sanctuary at St Martin le Grand in the early sixteenth century brought residents into close contact with outsiders, the precinct boundary running through the Bull’s Head tavern, where sanctuary men believed they could drink in a back room in safety.112 Precincts could hold contradictory purposes because their legal privileges were tied to a space that was under constant contestation and adaptation, existing at close quarters with and sometimes only ambiguously demarcated from surrounding neighbourhoods.

A second and related reason for the contradiction is that most of those who seem to have used extramural space to evade fame chose areas at some distance from their home. Henry Fyt sent his pregnant servant to give birth at a hospital away from his own Aldersgate neighbourhood, and Lawrence Gilis reneged on the marriage contract he made in St Botolph Aldgate, not the one he made close to his city centre home. While social boundaries were porous between precincts and surrounding areas, people who lived within the walls might calculate that fama of their misdeeds might not circulate far enough to make it to their own parish. Third, even when it was people from a neighbouring area who misbehaved in precinct space, like the gongfarmer who dumped rubbish in Norton Folgate’s bounds or the brawlers from Shoreditch, the precinct’s jurisdictional separation hindered any court presentation or prosecution that might have fixed fama of their misdeed in local memory. While liberty courts reported outsiders who were violent or disruptive, jurisdictional complexity probably made the task of constables in the liberties difficult. This would have been particularly the case when offenders were part of the highly mobile extramural population who might easily move on. There were thus practical barriers to the management of behaviour that perpetuated the ambiguous status of precinct space.

Conclusion

This essay has shown that reputation was not fixed in late medieval London and that people could reintegrate themselves and renegotiate their reputation with neighbours when rumour or their own behaviour threatened their position in local society. The majority of the local community, getting by as well as they could, maintained their place if they found themselves accused of misdemeanours by submitting themselves to compurgation or finding sureties, so long as they avoided being enough of a nuisance to warrant expulsion. Their social capital might be drawn from informal social networks; friends, fellow workers, gossips and employers who could step in to help in times of need. A smaller elite aspired to office-holding and influence, carefully seeking to gain and preserve social capital that was more closely tied to urban institutions such as guilds and juries. And yet, the constitution of this smaller group was contested and changeable. The wardmote jury acted as a testing ground for inclusion. Personal rivalries within this ‘elite’ produced consistory cases where authority could be questioned and undermined, albeit that greater social resources, including access to good witnesses and knowledge of how to ‘pre-construct’ testimony, would have been a considerable advantage. Unlike parish records, which often suggest a narrow, fixed elite who presented their decisions as unanimous and uncontroversial, the perspective I have presented on local society from church court cases is one that contains important nuances. One could be marginalized from the parish elite and yet still have a social network of friendship and support within the neighbourhood and be considered of good character. Even formal punishment appears not to have always broken social ties, given that neighbourhoods themselves contained a multiplicity of groups with their own patterns of sociability. Those friendships could turn into sureties, witnesses or compurgators in times of need.

The extramural areas themselves were spaces in which people could evade reputational damage. Their jurisdictional complexity both permitted some kinds of activity unwanted by respectable citizens elsewhere to continue with relative freedom and allowed citizens themselves to shirk social norms and the watchful eyes of their neighbours. Throughout this book, I have been careful not to simply equate spatial with social marginality, but this is a point where the two coincided and interacted with one another. This relationship was active and produced by the actions of Londoners. Extramural space was instrumentalized as a means to preserve good fame or at least to evade consequences. If, as Frank Rexroth argued, the extramural zone was considered beyond the ‘moral boundary’ of the city, it was a designation reinforced by the behaviour of citizens themselves. Just as the physical development of the extramural neighbourhoods was heavily influenced by the presence of religious houses, so was their social character. These twin legacies of urban development and jurisdictional separation cast a long shadow over early modern London, as many former precincts continued to hold liberty status despite the closure of the institutions from which that status had derived.

See endnotes and bibliography at source.

Chapter 5 (171-199) from The Margins of Late Medieval London, 1430-1540, by Charlotte Berry (University of London Press, 03.16.2022), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.