A small sample of the ways the planets and stars were portrayed in medieval manuscripts.

By Dr. Alison Hudson

Assistant Director, Undergraduate Research

Division of Student Success and Well-Being

University of Central Florida

By Dr. Peter Toth

Cornelia Stark Curator of Greek Collections

Bodleian Libraries

University of Oxford

By Dr. Taylor McCall

Managing Editor

Speculum: A Journal of Medieval Studies

By Dr. Laure Miolo

Dilts Research Fellow

Lyell Research Fellow in Latin Palaeography

Lincoln College

By Chantry Westwell

Author and Historian

After coming across a familiar-looking diagram of the planets in a 10th-century manuscript a few months ago, I asked my colleagues here at the British Library how cosmology was represented in some of the manuscripts on which they are currently working. The manuscripts they recommended offered a diverse array of ways to represent the planets and stars. Stargazing may have been a common human pastime throughout the ages, but how to depict the night sky was evidently another matter.

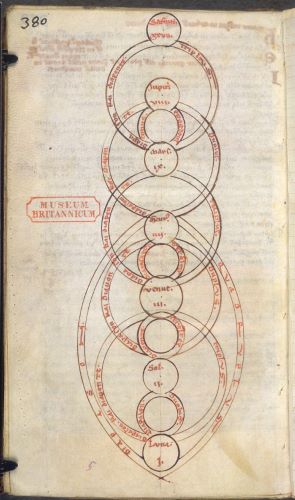

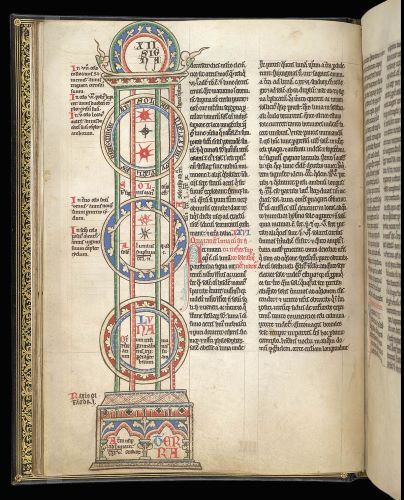

Today, planets are often depicted with a diagram which shows their orbits as a series of concentric circles. This type of diagram may have ancient roots, stretching back to Greek philosophers and astronomers like Ptolemy and Heraclides. Such models illustrated excerpts from the Roman thinker Pliny’s Natural History in some early medieval manuscripts. Over time, some copies were elaborated to take into account planets’ apparent retrogrades, leading to some spectacular models where planets are given overlapping or even zig-zagging paths. Diagrams using concentric circles were incorporated into medieval authors’ works, too. Such a diagram illustrates a copy of Isidore of Seville’s influential text, De Natura Rerum (On the Nature of Things), made in England in the 10th century. These diagrams reverse the positions of the Earth/moon and the sun, and some of the names of the planets are different from the names we use today, but otherwise they are largely recognizable to modern viewers.

In some cases, diagrams illustrating Pliny and other classical texts were also combined with theories attributed to Pythagoras about the relationship between musical tones, mathematical ratios and planets’ orbits. Hence, a 9th-century diagram includes notes about tonus (tones) in between the planets. These diagrams could be rather elaborate, as in the 13th-century example above.

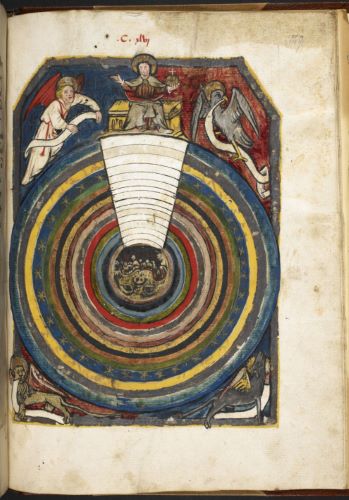

The concentric model was expanded in later medieval art to include the seven planets and the earth encircled by a layer of ‘fixed stars’ which was held up by angels. The elements of fire, air, water and earth were given their own layers, under the moon.

Other depictions of the ‘spheres’ could be even more elaborate, with Hell at the centre and the throne of God at the outermost layer.

But concentric circles were not the only way of depicting star systems in medieval manuscripts. By contrast, the model of the sun, moon and earth, from a 13th-century copy of Bede’s De temporibus, might look a bit alien to modern viewers.

Earth is represented by a house-/ tomb-/ reliquary-shaped box at the bottom of the diagram, while the moon is labelled in a roundel above it. According to the annotations on the side, the other roundels include Mercury, Venus and other planets, all the way up to Saturn, ‘in the 7th heaven’. The diagram accompanies a passage explaining ‘why the moon, though situated beneath the sun, sometimes appears to be above it’ (translated by F. Wallis, Bede: The Reckoning of Time (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1999), p. 77). While these diagrams look rather different from modern textbook representations of the sun, moon and earth, some of Bede’s text, updating to previous models of the universe, still stands. In particular, Bede is notable for being the first European to observe and record the connection between phases of the moon and the tides of the ocean.

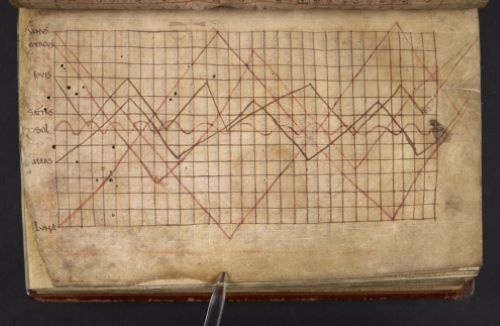

The diagram in a scientific miscellany made in the late 11th or early 12th century takes yet another approach, mapping planets’ orbits onto a sort of graph. The sun’s regular appearance in the sky here contrasts with the other planets’ (and the moon’s) more variable appearances over days, months and years.

Other depictions of cosmology and the stars prioritised artistic creativity over mathematical calculations.

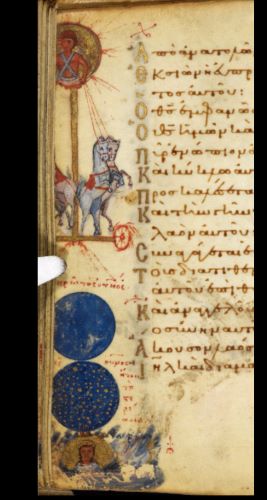

Byzantine manuscripts provide some stunning examples of the planets as personified, depicted containing tiny portraits.

Like the concentric model, these personified models were also based on classical sources, which meant that these common themes emerged even in manuscripts produced in distant regions. For example, 11th-century manuscripts from as far apart as Constantinople and England depict the sun as a charioteer.

Maps of the constellations were another way of representing the stars that was classically inspired and widespread in the Middle Ages: see our earlier blog post on Cicero’s ‘map to the stars’. Although the image of a night sky teeming with mythical monsters, ships and heroes contrasts with the model of orderly concentric orbits that began this post, we also use some of the same imagery of constellations today. See the similarities between an early medieval map of the constellations below and an advertisement for Air France which features in the British Library’s exhibition on Maps and the 20th Century (on until 1 March 2017).

This is just a small sample of the ways the planets and stars were portrayed in medieval manuscripts. It does not even begin to touch on diagrams outlining specific celestial events, like eclipses, phases of the moon and zodiac cycles. Hopefully, however, this post gives a small taste of the myriad of ways medieval people thought about and depicted the heavens.

Originally published by the British Library, 01.24.2017, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.