By Dr. Farah Karim-Cooper

Head of Higher Education and Research

Shakespeare’s Globe

Of all Shakespeare’s plays, it is Othello which reflects most vividly the multi-ethnic character of the Mediterranean basin in the 16th century. The Venetian army led by Othello, an African Moor, consists also of a Florentine (Cassio) and perhaps a Spaniard as well: the name ‘Iago’ is Spanish, and would have invoked for Shakespeare’s audience the name Santiago Matamoros, Saint James, the Moor-slayer, patron saint of Spain.

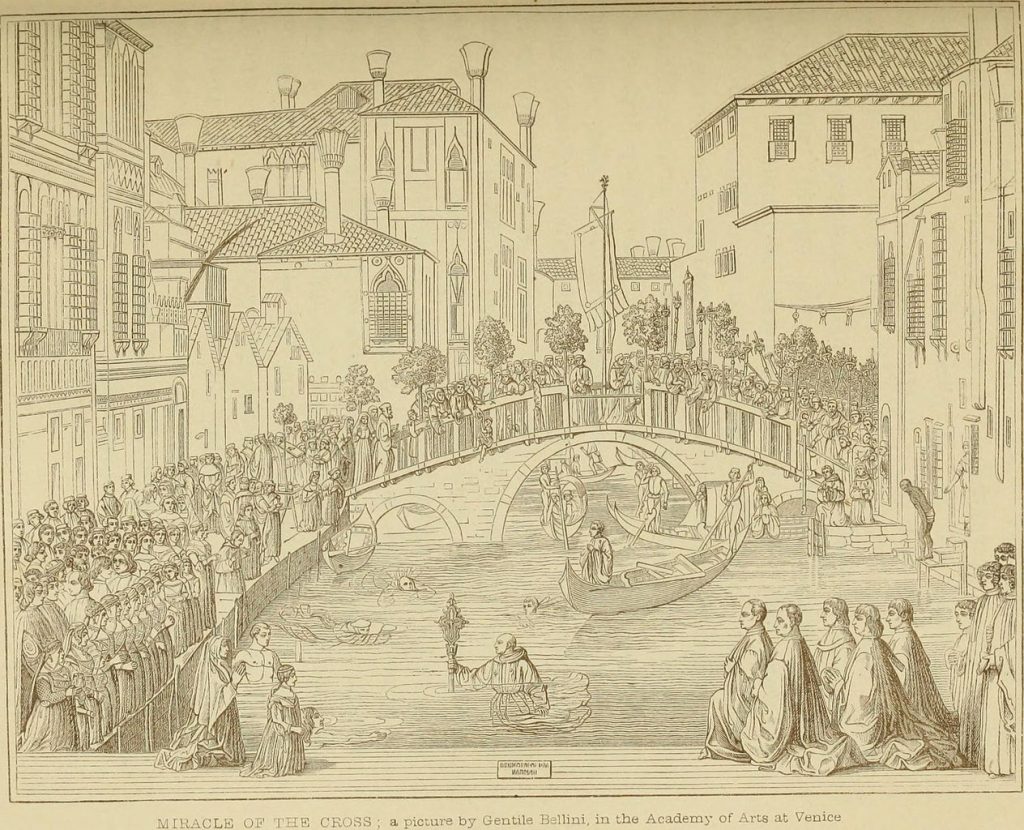

This shouldn’t surprise us, for Venice in the late 16th and early 17th centuries – the period in which Othello is set and when Shakespeare wrote his play – was still home to people of a wide variety of cultural and ethnic backgrounds. A detail from a late 15th-century painting by Vittore Carpaccio called ‘The Healing of the Possessed Man’ shows not only nobles, clerks and prelates, but also Turkish traders (in white turbans) and an African gondolier. The figures in the painting are gathered at the Rialto, which was the economic centre of the city and where a great variety of different ethnic communities lived and conducted business.

The English traveller Thomas Coryate’s early 17th-century account of his travels to Venice reveals that in the intervening century the city’s multi-cultural atmosphere had not diminished – rather the reverse. Venetian relations with the Ottomans may have been fraught with conflict (the war with the Turks is a constant presence in the background of the play), but there remained a rich exchange of material goods, culture and ideas with Turkish lands. Other European nations were growing more commercially confident, and maritime trade (as well as international piracy) in the Mediterranean basin flourished. The influx of immigrants into the city throughout the 16th century helped to reinforce an already well-established reputation for cosmopolitanism, which wasn’t limited to the city itself. Venetian dominions such as Cyprus (where most of the action takes place) were also peopled with representatives of diverse nations. We know from contemporary accounts that Venetians, Cypriots, Greeks, Jews and Turks lived on the island, which had been culturally diverse since the medieval period. This exciting cross-cultural dialogue contributed to a global impression of Venice as a city of great opportunity, wealth and magnificence.

Venetians themselves recorded the confluence of ‘strangers’ in their city. The historian and man of letters Francesco Sansovino writes about the ‘Florentine, Genovese, Milanese, Spanish, Turkish, and other merchants from different nations of the world’, who frequented the heart of Venice, St Mark’s Square. A traveller in Venice in the 1570s would observe ‘in this city an infinite number of men from different parts of the world, with diverse clothing, who come for trade; and truly it is a marvellous thing to see such a variety of persons, dressed in diverse habits’.

Indeed, what many contemporary commentators tended to notice about the foreigners in Venice was their clothing. The city was slightly paradoxical since it had sumptuary laws governing dress according to social hierarchy, but such laws were rarely enforced and a newly rich mercantile class clothed itself according to its financial, rather than social status. Coryat remarked that you will see ‘all manner of fashions of attire’, and that in St. Mark’s Square, ‘you may see many Polonians, Turkes, Jewes, Christians of all the famous regions of Christendome, and each nation distinguished from another by their proper and peculiar habits’. Foreigners often dressed in their own habits, creating, as Carpaccio’s painting suggests, a socially and multiculturally rich atmosphere that finds its way into Shakespeare’s play.

‘Strangers’ in Venice might live peaceably amidst Venetians, but that is not to suggest that racial tensions did not exist. Contradicting accounts of Venice from the period describe a city that ghettoised its ethnic minorities, while other accounts, such as those of Coryate and Sansovino, and images such as Carpaccio’s, describe a quite integrated and racially diverse society. Sansovino says of the Jewish community in Venice, that ‘as a result of trade, the Jews are extremely opulent and wealthy, and they prefer to live in Venice rather than in any other part of Italy. Since they are not subject to violence or tyranny here as they are elsewhere’.

So this multi-ethnic society and the blurring of social boundaries that accompanied it did not come without a sense of anxiety, whether in the Venice or the England of that time. Othello’s relationships with himself and to those around him reflect Renaissance imaginings of the exotic – of the cultural ‘other’ – that were at once glamorous and dangerous. In Shakespeare’s England the abhorrence of ‘otherness’ was profound, and this anxiety ripples upon the surface of Othello. The play opens with language that creates an extraordinarily ethnocentric atmosphere, but is this racial malevolence Venetian or English? The answer is both. What Shakespeare’s play gives us is a complex mixture. The Venetian civic, military and economic tolerance of foreigners is combined with a patrician aversion to people from outside the city contaminating their pure lineage (dramatised in Brabantio’s emotional response to Desdemona’s marriage). On top of that, Shakespeare introduces the pathological fear of ‘otherness’ and dark complexions that he had witnessed in his own culture. Just how much Shakespeare’s audience saw of itself and London reflected back at them through his representation of Venice will never be known. But what is clear is Shakespeare’s sense that the world he was living in resembled the one he was portraying: a diverse city full of arresting contradictions.

Originally published by the British Library, 03.15.2016, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.