The Roman empire was a highly connected place with richly varied cultural traditions.

By Dr. Kimberly Cassibry

Associate Professor of Art

Wellesley College

Introduction

A vivid red cloak fastened by a gemstone pin. A creamy white cloak over a tunic with a purple stripe. A v-shaped face and an oval one. Curly hair, wispy and thick. Brown eyes, golden and dark. Facial hair above lips and along a jawline. When we look closely at these painted portraits from Egypt, we see the faces and clothes of individuals living in the Roman empire around 140 C.E. Scholars debate whether they are relatives, friends, or lovers.

The painting captures the cultural complexity of their world. Sketched above their shoulders are bronze statues of gods, with mixed Greek and Egyptian attributes. An Egyptian date (15 Pachon), written in Greek letters, can be seen on the left. One sleeve has an embroidered swastika, an ancient Eurasian symbol of unending prosperity.

At the time the portraits were painted, the Roman empire’s territory stretched across northern Africa, western Asia, and Europe. All of these places had art and architectural traditions older than the empire itself. Some, like Egypt’s, were far older. Egypt had become a Roman province around 30 B.C.E., when the great pyramid at Giza was already 2,500 years old and considered a wonder of the ancient world. Pyramids were far from being relics of the past, however, because they were still being built. In the city of Rome, Italy, a magistrate named Gaius Cestius constructed one around 12 B.C.E. Steep proportions make his Roman tomb look like the Pyramids of Meroë (in modern Sudan) just beyond the Roman empire’s southern border.

Despite such powerful cultural legacies, art histories of the Roman empire often focus on the might of one city: Rome.

This chapter tells a different story, one concerned with the empire’s geographic breadth and cultural plurality. Focusing on portraits and public architecture reveals how one of the world’s largest empires was experienced by real people like the ones in the painting above. Reintroducing the city of Rome and its emperors at key moments allows them to join an ensemble of characters and settings in an art and architectural history that stretches empire-wide.

Ancient Rome and Globalization

Overview

Historical records date Rome’s founding to 753 B.C.E., and leaders expanded the city’s territory for the next thousand years. Archaeology shows a more complex picture of habitation over time, but the historical records treat 753 B.C.E. as the founding date.

Scholars have divided this long history into three eras defined by different governments:

753–509 B.C.E.

This is the Monarchy or Regal period, with a king and a senate. The Latin word for king is rex. After the end of the Regal period, when aristocrats forced the last king out of office, leaders of Rome would never again be called kings. In Latin, senatus derives from senex, meaning “old man.” In contrast to modern senates, the Roman senate was not elected directly, but instead included men who had held elected offices, called magistracies.

509–27 B.C.E

This is the period of the Republic, with elected magistrates and a senate. Magistrates were elected officials who administered the Roman government.

27 B.C.E.–330 C.E.

This is the period of Empire with an emperor, elected magistrates, and the enduring senate. The Latin word for emperor is imperator. This term had been used for successful generals during the Republic, and was only one of the titles Romans used for the principal leader during the Empire. Although emperors typically chose their successors, who could be a relative or any capable leader, the senate technically had to confirm the transfer of power.

This essay addresses the third phase, when Rome’s territory reached its greatest extent. Road systems and sailing routes created an early phase of globalization in this era, with people, commodities, and ideas moving through highly connected territories on three continents. Theories of globalization allow rapidly increasing connectivity to be studied across time periods, even if the connectivity did not extend around the globe.

Peace, Plunder, and the First Emperor

After a period of civil war, an aristocrat called Augustus became Rome’s first emperor in 27 B.C.E. As emperor, Augustus had extensive military power and ruled alongside elected officials and the Roman senate. Monuments from his reign reveal the complicated backstory of ongoing imperial expansion.

Augustus was the leader responsible for annexing Egypt. He commemorated this feat by seizing two obelisks from Heliopolis (Cairo), transporting them to Rome, and rededicating them as victory monuments.

The kingdom of Kush in Sudan, Africa, contested Rome’s claim to Egypt. Its representatives captured and mutilated a portrait of Augustus: the severed bronze head was placed beneath the steps of a Kushite temple. At the same time, the Parthian army from Iran seized Roman military standards while fighting the empire’s expansion in the eastern Mediterranean. Augustus’ reclaiming of these standards was presented as a great victory on the armor of what has become his most famous portrait (the Augustus of Primaporta).

These acts of looting—Augustus’ claiming of Egyptian obelisks, the Kushite claiming of a portrait of Augustus, and the Parthian claiming of Roman military standards—demonstrate how much cultural violence occurred as the empire’s borders expanded.

Many Gods, Many Temples

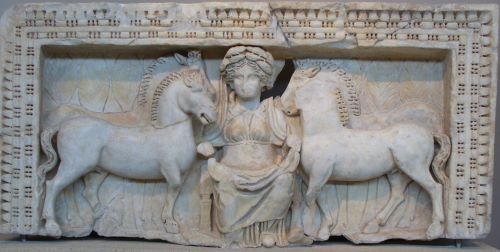

Most of the empire’s communities believed that there were many gods, and their polytheistic religions were open and fluid. Gods favored in one region could be worshiped anywhere. A good example is Epona, a Celtic goddess associated with horses. Honored extensively in France (Gaul), she became popular with Roman cavalry troops who spread her worship to many different regions of the empire. New gods could also be invented to address emerging concerns, and emperors and their heirs were sometimes honored as gods after their deaths.

A shared belief in reciprocity—that help from the gods should be rewarded with gifts—generated much of the empire’s art and architecture. Many religious sites pre-dating the empire’s expansion remained in use with new offerings. Amun’s sanctuary in Karnak, Athena’s Parthenon in Athens, and Sulis’ sacred spring at Bath all continued to attract worshippers.

In newly constructed temples, design and decoration varied widely. Nîmes (Nemausus, France) had a temple that resembled many in Rome, with a podium, central stairway, and encircling columns. This temple was dedicated to Augustus’ deceased grandsons, but altars and art throughout the city honored a wide range of deities, including Celtic ones and those favored by immigrants from distant lands.

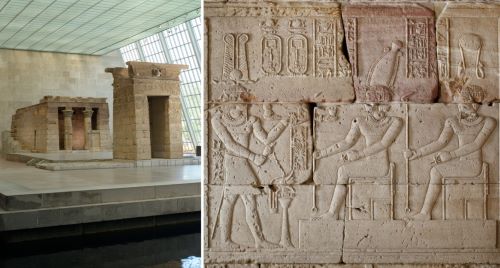

In Egypt, traditional building plans, column styles, and imagery persisted in many areas. One of the best examples is a small temple from Dendur, which honored the Egyptian goddess Isis and the deified sons of a local Nubian ruler. In the temple’s relief sculptures, Augustus appears as an Egyptian king wearing a ceremonial kilt and headdress and presenting offerings to Isis and other deities. This is one of many temples in Egypt where Roman emperors are shown fulfilling the king’s duty to the region’s gods.

Sports and Entertainment

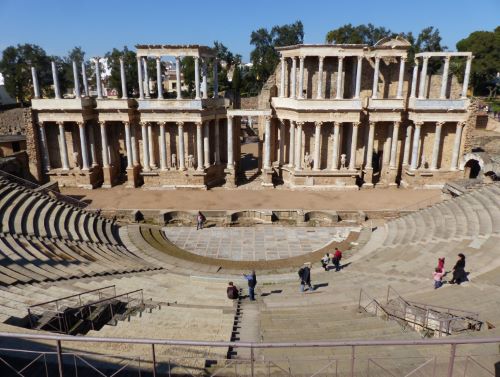

The empire’s residents could go to an amphitheater to attend gladiatorial fights and animal hunts; a circus for chariot races; a stadium for track and field events; a theater for comedies, tragedies, and mimes; and an odeum for concerts and poetry readings. Of these buildings, only the amphitheater developed in Italy; the rest arose in Greece, but were popular in many of the empire’s cities.

When Rome’s Colosseum was dedicated around 80 C.E., it became the empire’s largest gladiatorial venue. At least 273 amphitheaters eventually stood around the Mediterranean world, one of the most visible ways that cities changed during the era of Roman rule. Locally elected magistrates typically paid for these buildings and their events.

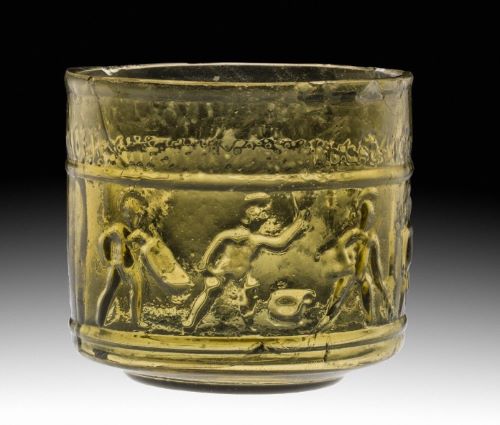

The gladiators who fought in them had low social status and short lives, and they were celebrated as sports heroes in art. The Latin term gladiator derives from gladius, meaning sword.

Emperors from Spain in Rome

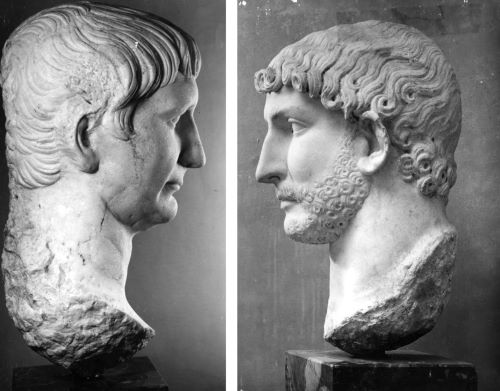

People from the empire’s provinces gradually took the lead in culture, politics, and the military. The territory of the empire was divided into administrative provinces called provinciae in Latin. The emperors Trajan and Hadrian hailed from Italica (an ancient Roman city in Spain), and came from mixed families of Italian colonists and Spanish elites.

The ground-breaking architect for these emperors was Apollodorus, a Greek-speaking Syrian from Roman Damascus.

In Rome, relief sculptures on a monumental column depict the emperor Trajan leading military campaigns in Romania (Dacia). One scene represents a bridge that Apollodorus designed for the Roman army to cross the Danube river. The bridge, made of masonry pillars and wooden archways, dominates the top of the scene. A religious ceremony led by Trajan takes place on the shore.

Another scene shows a military strike by a cavalry troop recruited from Roman Morocco (Mauretania). This troop (on the left) stands out because of its careful hairstyling with long ringlets. Dacian soldiers make a different impression. They appear (on the right) with unstyled hair and long messy beards, signs of barbarism in the eyes of the Roman elite.

While the relief sculptures celebrate the imperial work of many individuals from the provinces, they stereotype Dacians as barbarians to justify the invasion.

The Senate and Roman People (Senatus Populusque Romanus, SPQR) dedicated this sculpted column to Trajan to honor him for financing a new forum (town square) in Rome. Apollodorus was responsible for designing the forum, which required a hill to be scaled back. He also designed the neighboring market complex, where he used concrete to create curved spaces with vaulted ceilings. These advances in engineering culminated in the Pantheon, the magnificent domed temple now thought to have been initiated by Trajan, completed by Hadrian, and designed by Apollodorus. In these and many other ways, people from the provinces shaped the empire’s frontiers as well as Rome’s cityscape.

Cities, Forts, and Communities

Many of the empire’s cities and forts survive as archaeological sites, and each offers a different perspective on daily life.1 Pompeii, for instance, reveals how one of Italy’s oldest cities changed under Roman rule. The forts along Hadrian’s Wall in Britain preserve sculpted tombstones honoring people from as far away as Morocco. And at Dura-Europos, Syria, art and architecture document the coexistence of polytheism, Judaism, and Christianity on a border contested by the Parthian and Sasanian empires of Iran.

Portraits and Identities

Many of the empire’s residents encountered portraits in their daily lives. These images appeared in public squares, temple precincts, cemeteries, and homes. They were made in a range of media including statues, relief sculptures, paintings, cameos, and gems. Portraits also defined the empire’s coin-based monetary system, legitimized by images of the emperor and his family.

Some portraits prioritized recognizable resemblance (a realistic likeness), with flaws emphasized (verism) or minimized (idealism). Alternatively, some used generic bodies to emphasize social roles more than individuality. These approaches co-existed, and many portraits combined symbols, poses, and inscriptions to communicate complex identities.

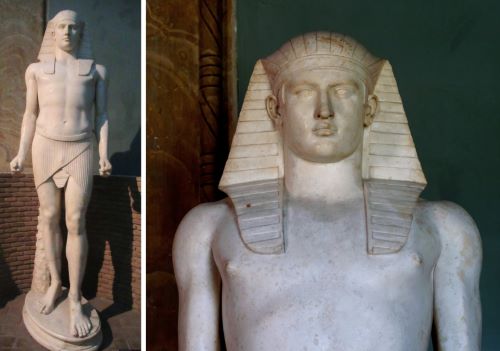

This statue, from Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli, presents an idealized likeness of the emperor Hadrian’s lover Antinous, who is shown in the imagined clothing of Osiris (the Egyptian god of the dead), an allusion to his untimely death in the Nile river and subsequent recognition as a god.

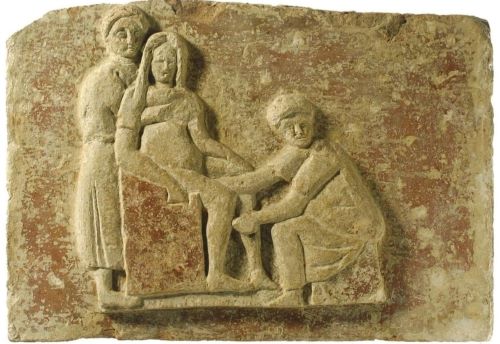

Although elites like Antinous were rarely depicted doing physical labor, people who worked for a living often emphasized professional pride in their tomb portraits. Scribonia Attica, a midwife at Ostia, showed herself at work.

Portraits also represented people with different levels of freedom: the empire’s population included free, enslaved, and formerly enslaved individuals. Enslaved persons often came from active war zones, especially in Europe, because generals could sell defiant populations for profit. Emancipation, the granting of freedom, was also widely practiced.

Much of our knowledge about freed people comes from the tombstones that they commissioned for themselves and their loved ones. They typically note their status in inscriptions, with libertus meaning a freedman and liberta meaning a freedwoman in Latin.

An Emperor from Libya and and Empress from Syria

In the late 2nd century C.E., another dynasty from the provinces claimed power. Septimius Severus came from an old family in Khoms (Lepcis Magna), Libya, where the Punic language was still spoken. His wife Julia Domna came from an old family in Homs (Emesa), Syria, where Syriac and Greek were still spoken. Although the empress’ role was ceremonial, Julia Domna traveled more than any of her predecessors, and her portraits survive in great numbers. The couple’s son Caracalla left a lasting mark on Rome’s cityscape by constructing a spectacular public bathing complex with soaring curved ceilings, colorful mosaic floors, and a statue collection.

Emperors Defeated in Iran

After the fall of the Severan dynasty in 235 C.E., emperors struggled to assert control over the empire’s vast territory. The Roman military suffered defeats, especially in battles against the Sasanian empire of Iran.2 Sasanian kings drew on their region’s long history of monumental art to commemorate their victories. Sasanian images of vanquished Roman emperors offer an important counter-narrative, because the Roman military is never shown losing in Roman art.

From Rome to Istanbul

To counter the chaos of the 3rd century, the Roman emperor Diocletian led an experiment in shared rule. Two senior emperors and two junior emperors divided the empire into quadrants and developed capital cities away from Rome. Portraits of this Tetrarchy, meaning the “rule of four,” emphasize visual similarities among the emperors sharing power.

The emperor Constantine I began as a tetrarch, but eventually re-established sole rule. He also acknowledged Christianity as one of the empire’s official religions and developed Constantinople (Istanbul, Türkiye) as his primary capital. Scholars consider his reign a turning point from the Roman Empire to the Byzantine Empire. These modern terms are misleading, however, because leaders based in Constantinople continued to call themselves Roman and their realm the Roman empire.

The word Byzantine comes from Byzantium, which was the city of Istanbul’s original name. When Constantine transformed Byzantium into his capital, he renamed it Constantinople, meaning “the city of Constantine.” This name persisted into the early 20th century, when Istanbul became the city’s official name.

Like all of the empire’s cities, Constantinople drew inspiration from Mediterranean-wide precedents. Rome’s own multicultural cityscape offered one model. The Byzantine emperor Theodosius I transported an ancient obelisk from Egypt to Istanbul, just as Augustus and other emperors had done for Rome.

The Politics of Cultural Heritage

Archaeological sites from the Roman era can be found in more than thirty modern nations, where they have been shaped by changing cultural traditions, archaeological practices, and heritage laws. In all of these lands, policies of reconstruction or destruction have served political movements aiming to build or break connections to the past.

To promote preservation, many places from the Roman empire are now recognized as UNESCO World Heritage sites. Yet Europe is over-represented on UNESCO’s list, and the empire’s territories are still unevenly addressed in teaching and learning resources. Emerging scholars can make an important contribution by developing expertise across the many fascinating regions that defined the Roman empire’s connected world.

Endnotes

- Other places well-preserved as archaeological sites include Herculaneum in Italy; Glanum and Vaison-la-Romaine in France; Baelo Claudio and Italica in Spain; Sarmizegetusa in Romania; Gamzigrad in Serbia; Ephesus and Aphrodisias in Turkey; Apamea and Palmyra in Syria; Dendera, Edfu, and Philae in Egypt; Lepcis Magna and Sabratha in Libya; Bulla Regia and Dougga in Tunisia; Djémila and Timgad in Algeria; and Volubilis in Morocco. Scattered remains from the era of Roman rule exist throughout these regions in cities and rural areas.

- Touraj Daryaee, “Persia and Rome: the Historical and Ideological Gaze,” Persia: Ancient Iran and the Classical World, edited by Jeffrey Spier, Timothy Potts, and Sara Cole (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2022), pp. 283–91.

Originally published by Smarthistory, 01.16.2024, under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.