Originally published by Newberry Digital Collections for the Classroom, 09.11.2017, Newberry Library, republished with permission for educational, non-commercial purposes.

Introduction

The city of Chicago provided a crucial battleground for a national struggle over the meaning of political radicalism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The term political radicalism refers to individuals and parties who advocate far-reaching political and social reform. During this period, writers usually applied the term radical to activists and parties on what is known as the left side of the political spectrum, such as Communists, socialists, and anarchists. Leftist radicals were also called Reds, after the color of their party flags. There were significant ideological differences between these parties and each party’s positions changed over time. But all of them rejected the concept of private property and promoted the rights of workers against those of the people for whom they worked, wealthy factory and business owners, known as capitalists.

From the 1880s through the 1960s, Chicagoans engaged in a passionate debate over how government should respond to political radicalism. On one side, were proponents of civil liberties, the freedoms and rights promised to every member of society by the U.S. Constitution. They argued that political radicals and their organizations were protected by the First Amendment, which guarantees freedom of speech. On the other side, were people primarily concerned with security. They wanted to maintain social order and protect the government from violence or radical change. These concerns increased during wartime. Many political radicals, like the workers they claimed to represent, were recent immigrants from northern and eastern Europe. Their opponents often raised alarms about foreign influences in the United States.

Adding to the complexity of these debates was the difficulty in defining who or what constituted a real threat to the United States. A small number of political radicals engaged in deliberately violent or overtly treasonous activities, such as bombings or espionage. But these people were affiliated with larger movements and parties that included many people committed to reforming, not overthrowing, the U.S. government and society. Many radicals sought workplace protections for laborers, African Americans, and women that are now widely accepted. They made important contributions, for example, to movements to prohibit child labor or to enforce an eight-hour workday. The documents that follow represent some of the milestones in Chicago’s history of political radicalism from the Haymarket Affair of 1886 through the Palmer raids of 1920 into the McCarthy era of the 1950s.

Anarchism and the Haymarket Affair

Nineteenth-century employers often expected workers to spend 12 to 14 hours a day, six days a week on the job. In the 1880s, anarchists, unionists, socialists, and reformers organized a national effort to demand an eight-hour workday. During the first week of May 1886, 35,000 Chicago workers walked off of their jobs in massive strikes to protest their lengthy work weeks. Some of these strikes involved violent skirmishes with the police. At least two strikers were killed on May 3.

In response, the next evening, roughly 1,500 people gathered at the West Randolph Street Haymarket, a market on the edge of the city where people bought hay for their horses. The May 4 rally featured fiery speeches from the city’s leading anarchists and labor leaders, but was a peaceful gathering. As the rally drew to a close, hundreds of policemen moved in to disperse the crowd. Someone threw a bomb at the police brigade, killing one officer instantly. The police responded with a barrage of bullets. An unknown number of demonstrators were killed or wounded. Sixty police officers were injured and eight eventually died.

Politicians and the press blamed anarchists for the violence. Although there was no evidence linking specific people to the bomb, eight men were convicted of murder on the basis of their political writings and speeches. Four men were executed; one committed suicide. The trial was later considered grossly unjust and, in 1893, the Illinois governor granted absolute pardon to the three, remaining, imprisoned defendants. The anarchist movement, however, never recovered from the trial.

These documents include passages and images from a history of the Haymarket Affair written by Captain Michael Schaak. Schaak commanded a Chicago Avenue police station in 1886 and played a large role in the arrests and prosecutions of anarchists following the Haymarket violence. Schaak included in his book the published principles and constitutions of several radical parties, such as the Workingmen’s Party of the United States, excerpted above. He also reproduced Judge Joseph E. Gary’s instructions to the jury, or guidelines on reaching a verdict.

Workers and Socialists during World War I

The International Workers of the World (IWW) is a radical labor organization that formed in Chicago in 1905 and still exists today. The IWW, whose members are known as Wobblies, encouraged workers across the country and around the world to unite to take control of economic resources such as factories and land. Like the anarchists involved in the Haymarket Affair, the Wobblies believed that economic resources should not be owned by individuals or private companies, but should belong to everyone. The organization urged direct action, such as strikes, rather than participation in the political process through elections. It was one of the first labor organizations to welcome women alongside men and to embrace people of all races and ethnicities.

The IWW became the target of federal raids as well as public animosity when it opposed the United States’ entry into World War I. These articles portray a 1915 strike by women garment workers and the 1917 federal raids of the IWW’s Chicago offices. In 1917 the U.S. Congress passed the Espionage Act, a law that made it a crime to interfere with military recruitment or operations or to support U.S. enemies during wartime. The following year, the federal government prosecuted over 100 IWW leaders on the grounds that their antiwar and labor organizing tactics violated the Espionage Act. All were convicted and sentenced to prison.

The First Red Scare

Anxiety about political radicalism and foreign influences further increased in the years following World War I as American politicians responded to events such as the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia and a series of bombings in U.S. cities. The period, known as the first Red Scare (1919-1920), culminated in coordinated raids of the offices and homes of political radicals, trade union militants, and immigrants. The raids were organized by U.S. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer and came to be known as the Palmer raids. Critics objected that the raids violated civil liberties, the freedoms protected by the U.S. Constitution. But officials defended their actions on the grounds that the radicals posed a real threat to the security of the U.S. government. Twenty members of the Communist Labor Party were among those arrested in January 1920. They were accused of plotting to overthrow the government.

The principle evidence against the men was, simply, their membership in the CLP. The well-known civil liberties attorney Clarence Darrow defended them in court. These documents include an editorial published by the Chicago Federation of Labor responding to the Palmer raids and an excerpt from Darrow’s courtroom defense of the Communists.

Union Organizing and Union Busting

Some owners of private companies feared that labor organizers would harm their businesses. They engaged in tactics, such as spying, to prevent workers from forming unions or joining radical political parties. Following World War II, federal and state governments as well as many private companies adopted a “loyalty-security program.” The program required employees to swear, not only that they had never committed treason or espionage, but also that they had never been a member or an associate of the Communist Party. These documents represent an early incarnation of these Cold War loyalty oaths.

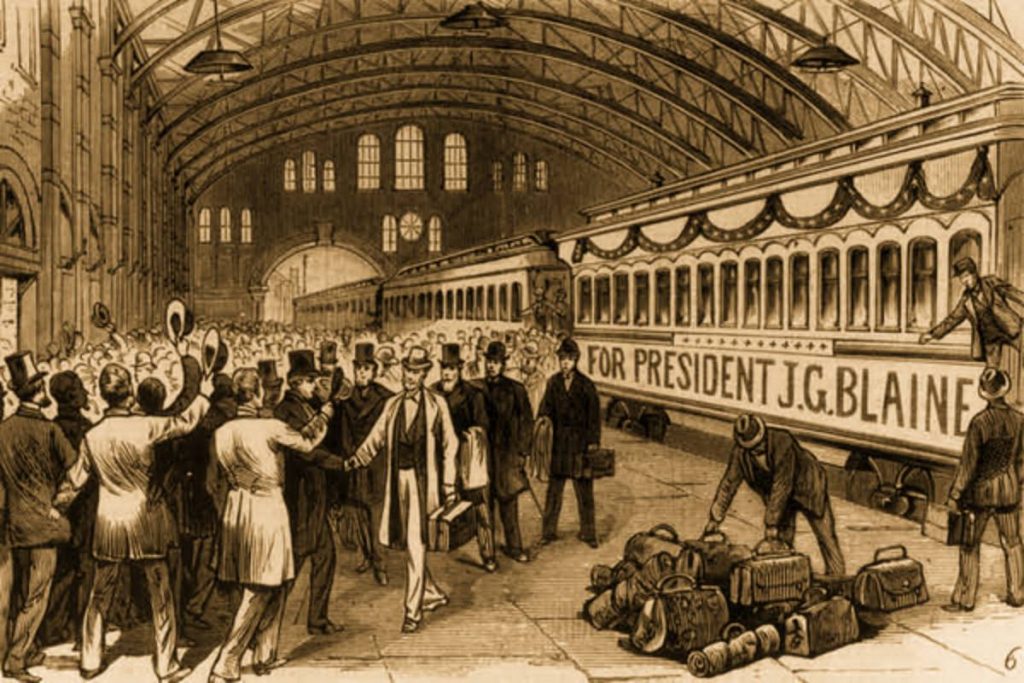

The Chicago-based Pullman Company was a leading manufacturer and operator of passenger coach railroad cars in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The company consistently opposed unionizing efforts on the part of its workers and urged them, instead, to participate in a company-controlled “employee representation plan.” Nevertheless, in the 1920s, Pullman’s African American porters and maids organized the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), under the leadership of A. Philip Randolph.

The union fought racial discrimination at the company and demanded treatment and wages for its members that were equal to those of white employees. The Pullman Company responded by requiring employees to sign loyalty oaths, such as the one included here, and by recruiting informants to report on union activities. The Pullman Company agreed to recognize the union in late 1937.

The Second Red Scare

These two books represent examples of post-World War II anticommunist thought. This period, extending from 1946 into the 1960s, is known as the second Red Scare. We know now that Soviet espionage did occur in the United States, primarily during World War II. However, many prominent Cold War anticommunists, such as Wisconsin senator Joseph McCarthy, did not limit their investigations to evidence of treason or spying. They singled out people simply for membership in or affiliation with the Communist Party. Americans from a variety of professions and trades were investigated and pressured to provide names of others who would become targets of investigation.

The books excerpted here offer ways of detecting Communists in the United States. Karl Baarslag had served as chairman of the Radio Officers Union in the American Federation of Labor (AFL) in 1931. His frustration in that position prompted him to write this advice manual on how to identify and counteract Communist influences in American labor unions. Anthony Trawick Bouscaren was a Wisconsin political science professor who specialized in United States-Soviet relations. He opened this guidebook with a 1956 quote from J. Edgar Hoover, warning that “the threat of Communist tyranny has not been lessened.” Bouscaren urged readers to “Know the enemy, then attack him.”

By Dr. Hana Layson

Manager of School and Educator Programs

Portland Art Museum

By Dr. David F. Krugler

Professor of History

University of Wisconsin-Platteville