Victoria Woodhull amassed a raft of “firsts” in her long and varied career.

Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

One brisk January morning in 1871, feminist leader Susan B. Anthony stepped off the train in Washington. She was in town for a huge suffrage convention and arrived early to buttonhole Congressmen beforehand. A scan of the newspapers confirmed what Anthony’s fellow lobbyist, Isabella Hooker, rushed up to tell her: scandalous Victoria Woodhull, spiritualist, stockbroker, and presidential candidate, would testify on women’s suffrage before the House Judiciary Committee, the very next day.

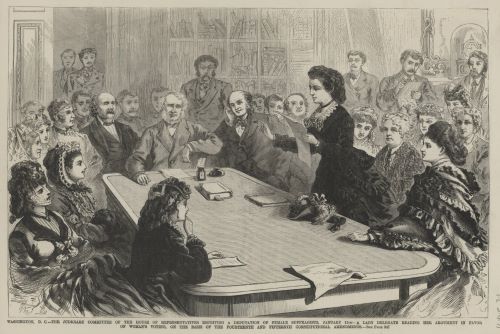

Victoria Woodhull amassed a raft of “firsts” in her long and varied career, and at that January 11 hearing, she added not one but two milestones. When she rose to address the Judiciary Committee, beginning in a shaky voice but soon with gathering power, Woodhull became the first woman to testify before a House committee. When her image appeared in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, she also became the subject of the first known image of a House committee hearing. The testimony marked a shift in how women lobbied Congress, while the print marked a turning point in newspapers’ depiction of “public women.” A closer look at the image shows how Leslie’s representation of a woman testifying before a committee of the House of Representatives gave credibility to Woodhull and women’s rights.

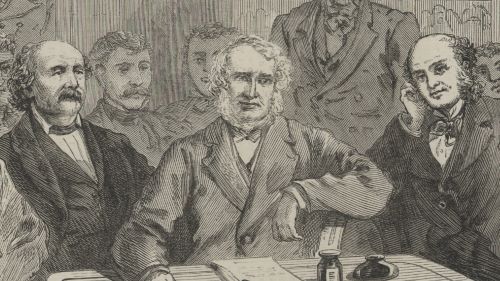

Reporters and diarists alike set down their accounts of the Judiciary Committee’s hearing that day. “The appearance of the motley assemblage,” gasped one, “was simply imposing.” The Leslie’s print provides portraits of the major players, giving the illustration a sense of authenticity. Three men at the end of the table are identifiable as major players in the hearing: Representatives Benjamin Butler of Massachusetts, John Bingham of Ohio, and William Loughridge of Iowa.

Butler, brilliant and famously radical, had arranged for the hearing, chaired by Bingham. Loughridge joined Butler as one of the few Representatives who agreed with Woodhull’s argument for women’s enfranchisement on the basis of equal protection provided all citizens and the right to vote provided by the 14th and 15th Amendments, respectively. Other committee members sat behind them, crammed into the small hearing room with observers and reporters, including perhaps the artist himself, who sketched the scene from his perch near the mantelpiece and clock.

Scores of suffragist convention-goers came to the hearing, too. One newspaper listed the names of 17 prominent women’s rights advocates in the room. The Leslie’s artist has given identifiable features to a few of the most important. Woodhull’s sister and fellow lobbyist, Tennie Claflin, sits at the hearing room table next to her sibling. Suffrage matriarch Elizabeth Cady Stanton, with her recognizable white curls, observes behind Woodhull. Across the table, Isabella Hooker, in profile, sits just past three anonymous, poised young women.

Woodhull, Claflin, and the three young women are the most interesting elements in the print, because rarely were middle-class, “respectable” women depicted appearing in public or engaged in civic affairs. The Leslie’s print of Woodhull’s committee testimony stands in stark contrast to other portrayals of women in public. Reputable female figures tended to be anonymous or illustrious, but rarely industrious. Representative Butler, in helping Woodhull and other suffragists through the portals of Congress, opened the door to validating the public discourse of women and legitimizing their new portrayal in popular news journals.

American women had been quietly (and then noisily) petitioning Congress for generations, but with this 1871 hearing, something changed. Woodhull’s voice, testifying before a House committee, meant that Congress recognized it as legitimate speech. Respectability followed suit. Dozens of reporters covered the convention. Woodhull, Butler, and Anthony knew the press would report the electrifying sight of a notorious woman giving testimony, too. Journals found themselves cloaking the suffragists with the legitimacy of Congress. Leslie’s complimented Woodhull for occupying “far higher ground than has usually been assumed by her coadjutors.” After the hearing, so many activists were in the Capitol that week that one reporter wrote that Congress was inundated with suffragists and “Washington became one grand conversational salon.”

Although images of Woodhull’s testimony in popular publications legitimized the work of women’s rights advocates, full citizenship came harder and more slowly, nearly 50 years later. The first woman in Congress arrived in 1917 and spoke early and often in favor of suffrage. For decades after Woodhull’s testimony, suffragists were still ignored, ridiculed, and generally shunted around the Capitol. Coverage in news journals wavered, sometimes portraying them as brave little ladies, sometimes as harlots or harpies, and very occasionally as real members of the congressional working world.

Until 1920, when the 19th Amendment to the Constitution granted women the right to vote nationally, the attitude to women in politics changed little from the day of Woodhull’s testimony. When Judiciary Committee Chairman Bingham greeted her that day in early January 1871, he was repulsed by her presence before the committee, and in fact, her life’s work. “Madam, you are no citizen,” he snorted, “you are a woman!”

Bibliography

- Josh Brown, “‘The Social and Sensational News of the Day’: Frank Leslie, The Days Doings, and Scandalous Pictorial News in Gilded Age New York,” New-York Journal of American History, 66:2

- Holly Pyne Connor, Off the Pedestal: New Women in the Art of Homer, Chase, and Sargent, Newark Museum (Newark, 2006)

- Amanda Frisken, Victoria Woodhull’s Sexual Revolution: Political Theater and the Popular Press in Nineteenth-Century America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004)

- Myra MacPherson, The Scarlet Sisters: Sex, Suffrage, and Scandal in the Gilded Age (New York: Hachette, 2014)

- Allison Sneider, Suffragists in an Imperial Age: U.S. Expansion and the Woman Question, 1870—1929 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008)

- Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan Brownell Anthony, Matilda Joslyn Gage, History of Woman Suffrage, Volume 2, (New York: Fowler & Wells, 1887)

- Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 4 February, 1871; New York Times, 11 January, 1871.

Originally published by the Office of the Historian, United States House of Representatives, 02.26.2018, to the public domain.