Syncletica’s significance also lies in her contribution to the recognition of female ascetic authority. Her counsel circulated alongside that of well-known male teachers.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Syncletica in the Landscape of Early Christian Asceticism

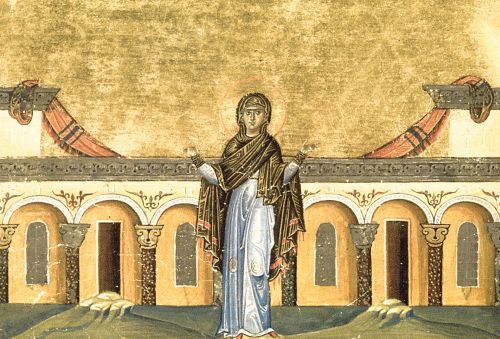

The figure of Syncletica of Alexandria occupies a rare place in the formation of early Christian asceticism. Her life is known through two bodies of material that survive from late antiquity. The first is the Life of Blessed Syncletica, attributed to Pseudo Athanasius, a Greek hagiographical work that circulated in monastic circles by the fifth century.1 The second is a series of sayings placed alongside those of the Desert Fathers in the Apophthegmata Patrum, which preserves the voices of early ascetic teachers in Egypt.2 Together, these sources provide the outline of a woman who renounced wealth, embraced enclosure with her blind sister, and became a guide for others seeking a disciplined spiritual life. They also reveal the highly selective and stylized ways early Christians remembered their ascetic exemplars.

Syncletica lived within the intellectual and spiritual ferment of fourth century Alexandria. The city was marked by theological debate, philosophical schools, and an expanding Christian presence that produced both urban ascetics and desert dwellers.3 Her withdrawal did not follow the pattern of figures like Antony, who sought the literal desert, but instead created a form of ascetic life at the margins of the city itself. The biographical tradition presents her separation as a deliberate movement into obscurity and silence, shaped by the broader culture of renunciation that took root in Egypt during this period.4

Her teachings survive only in fragments, yet they show a distinctive voice concerned with endurance, self mastery, and inner struggle. These sayings indicate an instructor who valued discipline more than spectacle and who reflected the theological and social tensions of her urban environment.5 Although the surviving texts cannot be read as straightforward biography, they illuminate the ways in which female ascetics participated in and shaped early Christian spiritual traditions. Syncletica stands at the intersection of gender, authority, and renunciation, offering a rare window into the religious imagination of late antiquity.6

Alexandria and Ascetic Culture: The World Syncletica Entered

Fourth century Alexandria was a city where intellectual, religious, and social forces collided with unusual intensity. Its Christian communities struggled over questions of doctrine and authority while sharing streets with philosophical schools that had existed for centuries.7 This environment offered aspiring ascetics a complex set of models. There were Platonists who sought purification through disciplined living, Jewish traditions shaped by scriptural study, and Christian thinkers who promoted renunciation as a path toward spiritual knowledge. Syncletica’s withdrawal took shape within this mix of influences, not in isolation from the urban patterns that shaped daily life.

Asceticism in Alexandria was never confined to the desert. A substantial number of renunciants lived within or just outside the city, forming networks of spiritual teachers who engaged with the concerns of urban Christians.8 The emergence of consecrated virgins created a recognized sphere in which women could claim forms of authority separate from family structures.9 The presence of these women within Alexandria’s religious life demonstrates that Syncletica’s decision to renounce wealth and retreat into obscurity had precedents, although her later influence suggests that she became one of the more prominent representatives of this path.

The pressures of the city helped define the kinds of renunciation that developed there. As theological conflict between supporters and opponents of Athanasius intensified, ascetic groups often became aligned with larger political and ecclesial movements.10 These tensions shaped the spirituality of renunciants, encouraging some to idealize withdrawal as a form of stability in a city marked by unrest. Syncletica’s enclosure with her blind sister reflects one version of this pattern. Her setting was neither the harsh solitude of the desert nor the structured life of a monastic community. It was instead a small domestic cell that echoed the urban asceticism already present in Alexandria.

Scholars have noted that Alexandria’s distinctive blend of philosophy and Christian devotion influenced the spirituality of its ascetics.11 This influence appears indirectly in the sayings attributed to Syncletica, which stress discernment, interiority, and endurance rather than dramatic feats. The intellectual environment of the city, with its long history of allegorical interpretation and disciplined study, offered tools that shaped ascetic self understanding. Her teachings reflect a sensibility formed within this context, drawing on traditions that valued inner transformation more than outward withdrawal.

The Life of Syncletica (Pseudo Athanasius): Genre, Purpose, and Limits

The Life of Blessed Syncletica survives as a hagiographical narrative whose authorship was attributed to Athanasius in antiquity, although modern scholarship identifies it as the work of an anonymous writer shaped by Alexandrian ascetic traditions.12 Its structure follows familiar patterns seen in other ascetic biographies of the period. These include descriptions of renunciation, spiritual struggle, and final perseverance through suffering. The presence of these motifs places the Life within a literary tradition that used exemplary figures to teach readers how to interpret ascetic discipline. This genre relied on stylized storytelling, which means that historical reconstruction must begin with caution rather than certainty.

The narrative presents Syncletica as a woman of aristocratic background who distributed her wealth and embraced a life of enclosure on the margins of the city.13 Her decision to withdraw alongside her blind sister forms one of the distinctive elements of the text. It highlights a variation of ascetic practice that did not depend on complete isolation but instead developed within a small domestic cell. This environment becomes the setting for her instruction to those who sought her guidance. The Life portrays her enclosure not as passive retreat but as a form of leadership grounded in restraint, patience, and physical hardship.

A comparison with the Life of Antony reveals how closely the author of the Syncletica narrative followed established hagiographical conventions. Antony withdraws into the desert and becomes the model of radical solitude, while Syncletica’s renunciation remains closer to the urban world.14 Yet both texts emphasize a progression from initial withdrawal to recognized spiritual authority. The author constructs Syncletica’s illness and long decline as the final stage of her spiritual struggle. The presentation of physical suffering as a means of purification is a recurrent theme in early ascetic literature, which suggests that the narrative aimed to reinforce familiar ideals rather than to document medical detail.

The text also shows how hagiographical writing shaped perceptions of female authority. Syncletica is portrayed as a figure whose wisdom emerged through endurance and whose influence rests on her ability to interpret spiritual difficulties for others.15 The framing of her speech patterns, the organization of her counsel, and the emphasis on discernment reflect the didactic goals of the author. Her death is described with imagery that emphasizes her constancy, which reinforces the narrative’s purpose as a model rather than a biography in the modern sense.

Modern scholars have paid close attention to the Life because it illustrates how early Christian writers constructed the spiritual identity of female ascetics.16 The narrative reveals the limits of hagiography as historical evidence, yet it remains indispensable for understanding how communities valued women who embraced renunciation. The interplay between literary convention and local urban setting suggests that the author sought to integrate Syncletica into a tradition dominated by male figures while preserving features that made her example recognizably distinct. This mixture of imitation and innovation provides essential insight into the development of female ascetic authority in late antiquity.

Syncletica’s Teachings in the Apophthegmata: Themes, Imagery, and Spiritual Pedagogy

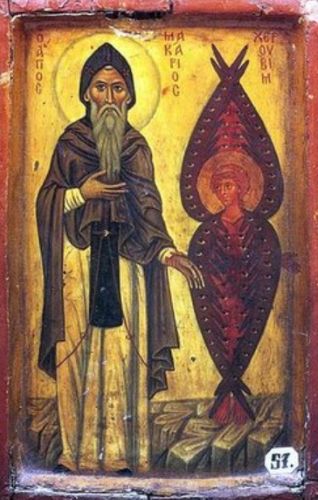

The sayings attributed to Syncletica in the Apophthegmata Patrum provide the clearest view of her spiritual instruction. They appear within the larger alphabetical collection that preserves the teachings of figures such as Antony, Poemen, and Macarius, yet they retain an identifiable voice shaped by her experiences of enclosure and endurance.17 Her sayings emphasize the inner landscape of struggle more than dramatic feats. This inwardness reflects a form of spirituality grounded in patience and self examination rather than the pursuit of isolation or physical extremes. The brevity of the sayings does not diminish their complexity, since many employ metaphors that encourage reflection rather than prescribe rigid solutions.

One of the dominant themes in her instruction is the cultivation of discernment. Several of her sayings encourage vigilance toward interior states, urging the practitioner to recognize how thoughts take shape and influence the soul.18 This approach aligns her with Alexandrian traditions that valued the disciplined interpretation of inward movements. The emphasis on discernment reveals a pedagogy in which spiritual progress requires careful attention to the gradual accumulation of habits. Her teaching style moves the reader toward steady transformation rather than sudden revelation.

Another recurring theme is the endurance of suffering. Syncletica’s sayings describe hardship not as an end in itself but as a condition that reveals the depth of commitment.19 Her reflections often turn toward images of fire, struggle, and labor that convey the effort required for purification. These metaphors echo the broader language of early monastic writers, yet they appear in her instruction with a distinct pastoral tone. The focus is not on heroic ascetic feats but on the slow work of perseverance. This emphasis reflects an environment where physical weakness, illness, and daily constraints shaped the spiritual journey.

Her teachings also reveal an attentiveness to community and relational responsibility. Although she lived in enclosure, the preserved sayings show concern for those who sought her counsel.20 She warns against pride in ascetic accomplishments and encourages humility toward those who struggle differently. These elements indicate a form of leadership that did not depend on public authority or institutional office. Instead, the sayings present her as a guide whose wisdom emerged from lived experience and careful observation.

Scholars have noted that Syncletica’s voice stands apart from male counterparts in the collection because her imagery often draws upon domestic and embodied experiences.21 The use of metaphors related to illness, household tasks, and ordinary labor creates a vocabulary accessible to a wider audience of ascetics. This feature suggests that her instruction resonated with those whose renunciation unfolded within or near urban settings. Her teachings demonstrate that early Christian asceticism included a range of pedagogical styles shaped by gender, environment, and daily circumstance.

Gender, Authority, and the Desert: The Significance of Syncletica as a “Desert Mother”

Syncletica’s presence within the ascetic tradition complicates the assumption that early Christian spiritual authority was primarily male. Her inclusion in the Apophthegmata Patrum demonstrates that the compilers recognized her instruction as part of the same teaching world that valued the voices of Antony, Macarius, and other prominent figures.22 Although she did not withdraw into the arid wilderness that shaped the ideal of the Desert Father, the narrative traditions surrounding her life show that authority could emerge from withdrawal practiced in an urban fringe. This demonstrates a broader range of ascetic models than the solitary desert anchorite.

Female ascetics in late antiquity negotiated their renunciation within social systems that placed strong expectations on women regarding domestic roles, kinship networks, and propriety.23 Syncletica’s withdrawal with her blind sister fits within this context by providing an enclosure that preserved both separation and responsibility. Her enclosure did not sever social ties entirely, since visitors sought her counsel, yet it created a boundary that allowed her to construct an identity centered on discipline and spiritual discernment. Her practices show how women integrated ascetic life into the social and architectural spaces available to them.

The sayings attributed to other Desert Mothers, such as Sarah and Theodora, reveal themes similar to those found in Syncletica’s instruction.24 These women became teachers through the interpretive labor of addressing spiritual difficulties, not through formal office or institutional authority. The presence of their sayings within the same collections as male teachers indicates that the tradition valued their insight. Syncletica’s voice, with its attention to perseverance and inward struggle, demonstrates that women participated in shaping early monastic pedagogy in meaningful ways.

Syncletica’s authority was constructed through the perception of her sanctity rather than through public acts of leadership.25 The hagiographical narrative emphasizes her gradual acceptance of visitors who sought guidance, suggesting that discipleship formed around her through reputation and personal encounter. This model of influence mirrored patterns seen elsewhere in Alexandrian asceticism, where spiritual teachers gained authority through counsel rather than through hierarchical appointment. Her withdrawal created a threshold that controlled access to her presence, reinforcing the ascetic value placed on silence and discernment.

Her example also shaped later understandings of female ascetic life in the Byzantine world. Scholars have traced the reception of her teachings in monastic literature that drew upon the sayings tradition to articulate the virtues of constancy, humility, and endurance.26 Her presence in these texts demonstrates that later ascetic communities preserved her instruction as part of the memory of early Christian spirituality. This continuity shows that her authority extended beyond the immediate setting of her enclosure and shaped theological reflection long after her death.

Syncletica’s significance lies not only in her preserved sayings but also in the broader cultural understanding of what a woman could become within early Christian asceticism.27 She embodied a form of leadership grounded in experience rather than institutional power, and her practices illustrated how renunciation could adapt to urban environments. Her life demonstrates that early Christian spirituality did not rely on a single model of holiness but developed through multiple forms of withdrawal and instruction. Her role as a Desert Mother remains a crucial part of that diversity.

Conclusion: Syncletica’s Legacy and the Shape of Christian Ascetic Thought

Syncletica’s legacy cannot be separated from the fragmentary nature of the sources that preserve her memory. The Life attributed to Pseudo Athanasius provides a narrative shaped by ascetic ideals, while the sayings in the Apophthegmata Patrum reflect the concise instruction that circulated among early monastic communities.28 Together, these texts reveal a figure whose authority was rooted in personal discipline and spiritual discernment rather than the institutional roles available to men in late antiquity. Her life demonstrates the porous boundary between urban and desert asceticism, showing that withdrawal could occur within varied environments without losing its transformative purpose.

Her teachings highlight an interior spirituality that valued patience, humility, and endurance as central practices. The metaphors present in her sayings, often drawn from daily tasks and physical experience, offer a distinct approach to the ascetic life.29 These images allowed her instruction to reach those who sought a form of renunciation adapted to the constraints of ordinary settings. Her spiritual pedagogy reveals a concern for gradual transformation rather than extraordinary feats, which sets her teaching apart within a tradition known for dramatic narratives of isolation.

Syncletica’s significance also lies in her contribution to the recognition of female ascetic authority. Her counsel circulated alongside that of well-known male teachers, demonstrating that early Christian spiritual instruction was not confined to a single gendered model.30 The respect accorded to her sayings in later monastic literature shows that women played a meaningful role in shaping ascetic ideals. Her life and teaching add dimension to the study of late ancient Christianity by illustrating how women adapted renunciation to the spaces available to them while cultivating forms of leadership grounded in wisdom and experience.

Modern scholarship continues to return to Syncletica as a figure who broadens the understanding of how ascetic life developed in Alexandria. Her example challenges the notion that the desert was the only significant site of spiritual formation and instead underscores the importance of the urban fringe as a setting for disciplined renunciation.31 Her memory persists because it demonstrates the range of ways early Christians sought holiness and the variety of voices that shaped the foundations of monastic spirituality. Syncletica remains a vital witness to the diversity and depth of early Christian ascetic thought.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Elizabeth A. Clark, trans., The Life of Blessed Syncletica in Women in the Early Church (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 1983).

- Benedicta Ward, trans., The Sayings of the Desert Fathers (Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, 1975).

- David Brakke, Athanasius and the Politics of Asceticism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), 8–15.

- Derwas J. Chitty, The Desert a City (Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, 1977), 17–28.

- Ward, Sayings of the Desert Fathers, 201–203.

- Susanna Elm, Virgins of God: The Making of Asceticism in Late Antiquity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994), 252–258.

- David Brakke, Athanasius and the Politics of Asceticism, 3–12.

- Derwas J. Chitty, The Desert a City, 19–24.

- Elm, Virgins of God, 42–55.

- Philip Rousseau, Ascetics, Authority, and the Church (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1978), 87–103.

- Kate Cooper, Band of Angels: The Forgotten World of Early Christian Women (London: Atlantic Books, 2013), 36–44.

- Clark, trans., The Life of Blessed Syncletica, 1–3.

- Clark, Life of Blessed Syncletica, 5–7.

- Athanasius, Life of Antony, trans. Robert C. Gregg (New York: Paulist Press, 1980), 5–12.

- Clark, Life of Blessed Syncletica, 14–17.

- William Harmless, Desert Christians: An Introduction to the Literature of Early Monasticism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 174–178.

- Ward, trans., The Sayings of the Desert Fathers, 201–203.

- Jean-Claude Guy, ed., Les Apophtegmes des Pères: Collection Systématique (Sources Chrétiennes 387, Paris: Cerf, 1992), 416–420.

- Ward, Sayings of the Desert Fathers, 202.

- Graham Gould, The Desert Fathers on Monastic Community (London: Mowbray, 1993), 54–57.

- Elm, Virgins of God, 263–268.

- Clark, trans., The Life of Blessed Syncletica in Women in the Early Church, 1–2.

- Elm, Virgins of God, 42–55.

- Ward, trans., Sayings of the Desert Fathers, 209–214.

- Gould, The Desert Fathers on Monastic Community, 54–60.

- Harmless, Desert Christians, 174–180.

- Cooper, Band of Angels, 37–45.

- Clark, trans., The Life of Blessed Syncletica in Women in the Early Church, 1–7.

- Ward, trans., The Sayings of the Desert Fathers, 201–203.

- Elm, Virgins of God, 252–268.

- Harmless, Desert Christians, 170–181.

Bibliography

- Athanasius. Life of Antony. Translated by Robert C. Gregg. New York: Paulist Press, 1980.

- Brakke, David. Athanasius and the Politics of Asceticism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995.

- Chitty, Derwas J. The Desert a City. Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, 1977.

- Clark, Elizabeth A., trans. The Life of Blessed Syncletica. In Women in the Early Church, 1–31. Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 1983.

- Cooper, Kate. Band of Angels: The Forgotten World of Early Christian Women. London: Atlantic Books, 2013.

- Elm, Susanna. Virgins of God: The Making of Asceticism in Late Antiquity. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994.

- Gould, Graham. The Desert Fathers on Monastic Community. London: Mowbray, 1993.

- Guy, Jean-Claude, ed. Les Apophtegmes des Pères: Collection Systématique. Sources Chrétiennes 387. Paris: Cerf, 1992.

- Harmless, William. Desert Christians: An Introduction to the Literature of Early Monasticism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Rousseau, Philip. Ascetics, Authority, and the Church. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1978.

- Ward, Benedicta, trans. The Sayings of the Desert Fathers. Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, 1975.

Originally published by Brewminate, 11.27.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.