Slave trading in Europe from Late Antiquity to the twelfth century.

By Dr. Christopher Paolella

Professor of History

Valencia College

Introduction

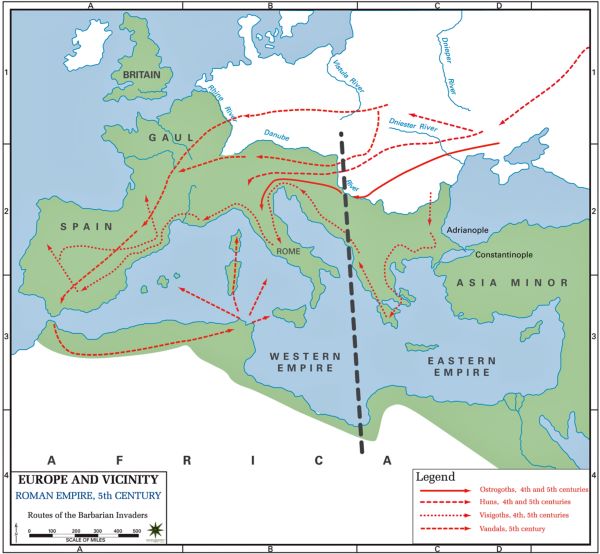

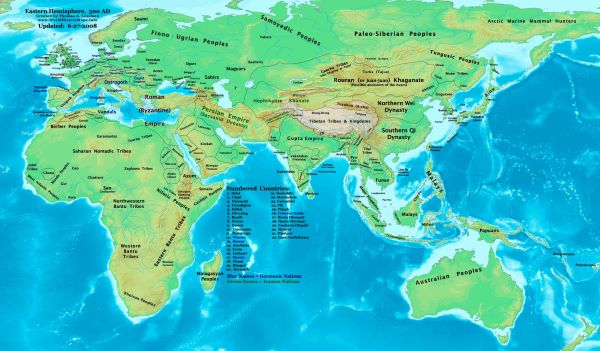

The image of the early medieval slave trade evokes the violence and terror of sudden raids, of slavers dealing in men, women, and children on Mediterranean beaches, and of the rancorous noise and abject humiliation of the market and the auction block. The commercial and communications networks that allowed human trafficking to flourish in Late Antiquity spanned the Mediterranean and Black Seas, but eventually fractured and regionalized over the course of the sixth and seventh centuries. This article will examine these trends in human trafficking patterns in detail, but before we begin, I propose two arguments. First, I argue that human trafficking is adaptive, allowing it to persist in many different socioeconomic and political environments. This adaptability is demonstrated in a number of ways. Human trafficking activity conforms to the socioeconomic systems and political environments in which it takes place, and historically traffickers were both raiders and merchants, which meant that raiding, trading, and trafficking blended and were difficult to disentangle. As the roles of raider, merchant, and trafficker merged, so too did trade routes and trafficking routes, and thus medieval efforts to suppress trafficking also meant the suppression of wider economic activity. Finally, although trafficking networks connected with one another to create wider and more intricate webs of operation, these networks could also operate independently of each other. For example, long-distance trafficking routes abated while local and regional routes persisted or even grew over the course of time, as I will demonstrate.

Second, I argue that centralized political authority is necessary to suppress trafficking; however, that centralized authority must actively commit to and maintain suppression efforts. Centralized political authority may actively engage in human trafficking activities, such as the Byzantine Empire between the eighth and eleventh centuries, or encourage human trafficking by sanctioning the slave trade, institutionalizing markets, regulating the trade to protect buyers, and by authorizing the support of bureaucratic, religious, and financial institutions for human traffickers, as the Roman Empire did at the height of its power. Conversely, a centralized political authority may encourage human trafficking by ignoring the problem or through passive acceptance, which might take the form of legislative inaction or of bureaucratic corruption or incompetence, as demonstrated by the Late Roman Empire in the fifth century. Finally, political decentralization allows human trafficking to flourish by fracturing political authority and thus suppression efforts, a dynamic we see in the post-Roman West. The fragmentation of society along political, cultural, and religious lines creates numerous ‘others’ who are considered outside of one’s own community and thus fair game for abduction and enslavement. The suppression of traffickers in a politically decentralized area becomes much more difficult because all polities must first agree to suppress traffickers, and then they must commit to suppression through sustained and coordinated effort.

I have outlined the different systems of medieval exchange and the mutable roles of chattel slaves within those different exchange systems; I also outlined a general typology of trade networks: long-distance, regional, and local. I now turn to a broad overview of human trafficking patterns across Late Antiquity and the early Middle Ages. In some periods, long-distance trafficking abated, while local and regional trafficking intensified. In other periods, long-distance trafficking intensified, while local and regional trafficking patterns remained robust and active. Trafficking networks, whether long-distance, regional, or local, may operate independently or cooperate with one another as circumstances permit. Authorities may alternatively aid and attempt to suppress traffickers, but it will become clear that human trafficking is dependent upon neither decentralized political authority nor strong centralized authority, but rather can adapt to either political climate. However, the suppression of human trafficking is in fact dependent upon a strong centralized authority.

For the sake of clarity, I have broken our time frame – from Late Antiquity to the twelfth century – into periods in which trafficking networks follow similar patterns. Thus we have a period of intense long-distance trafficking in the Late Empire, an abatement of long-distance trafficking and an intensification of local and regional trafficking networks from the sixth century through the eighth centuries, followed by a renewed period of intensification in long-distance trafficking operating, in conjunction with robust local and regional trafficking, from the ninth century through the first half of the eleventh. We then can observe a gradual decline in long-distance trafficking across Western Europe beginning in roughly the second half of the eleventh century that continues into the twelfth, when long-distance human trafficking patterns reoriented towards the Mediterranean. Nevertheless, local and regional trafficking networks persisted, albeit in attenuated form, across Western Europe.

The Late Empire: Rome in the Fourth and Fifth Centuries

The Roman Empire was rare in the history of ancient human civilization in that it represented a coherent political and economic system, although the degree to which that coherence affected everyday life differed in its many provinces. The Empire in the fourth century was characterized by integrated economies, long-distance exchange, and commercial production. As Kyle Harper observes, ‘it was a world built around money.’1 In general, the Roman political and economic system permeated everyday life in areas closely tied to the Mediterranean Sea, while outlying areas, such as northern Gaul, the high plateau of Anatolia, and inland Iberia, experienced Roman political power and the allure of its culture but maintained some cultural and economic autonomy from the distant capitals.2 Long-distance human trafficking networks in Late Antiquity involved local and regional trafficking networks, as well as long-distance trafficking that piggybacked on other long-distance trade routes and well-known sea lanes that supplied Rome (and later Constantinople) and the legions with regular grain and olive oil shipments.3 These long-distance grain shipments, known collectively as annona, supported long-distance trade because annona merchants and their contracted ship captains could use the extra storage space in their ships for goods destined for foreign markets. Laws governing imperial contracts with shippers stipulated that captains had to return to their home berths within two years of making their annona shipments in order to resupply for the next run.4

The long-distance sea lanes were thus established and maintained by these institutionalized supply runs, creating an integrated Mediterranean economy. For example, the Expositio totius mundi et gentium, written in the fourth century by an anonymous merchant, serves as a practical guide to the best markets for cheese, wine, oils, grains, textiles, and slaves, all of which were interwoven seamlessly into wider Mediterranean trade networks.5 The intensity of circulation, once cemented by the needs of the state, created its own patterns of commercial exchange.6 In the West, the annona shipments established the main commercial routes that then continued to operate between Rome and North Africa for some two centuries after the Vandal conquests cut off the grain shipments themselves.

Long-Distance, Regional, and Local Trafficking Networks

Long-distance trade and long-distance trafficking networks were indistinguishable at this time, as evidenced by Christian diatribes against the slave trade in the late fourth and early fifth centuries. For example, John Chrysostom (349–407) presumed that slavers lived in fear of being discovered and so sold their captives in distant markets, in order to minimize the chances of the victim finding a member of her kinship network.7 Cyril of Alexandria (376–444) excoriated not just slave traders but also their buyers, who he claimed simply feigned ignorance in order to buy foreign children whom they knew to be free.8 In 428, Augustine (354–430) bemoaned the plight of those abducted and channeled into long-distance trafficking networks in a pained letter to his friend Bishop Alypius of Tegaste (d. 430), in modern-day Algeria: ‘Many [trafficking victims] are bought back from the barbarians, but, transported to provinces across the sea, these [trafficking victims] have scant possibility of such a form of rescue.’9

Hippo had to contend with more than long-distance slavers. Even as the Vandals were conquering North Africa in the 420s, Augustine wrote that regional slave traders, displaced by unrest in their usual haunts on the frontiers of the Empire near Mauritania, had then descended onto his province to purchase slaves captured in the confusion of the Vandal invasions, who were marched down to the harbor, ‘like a neverending stream’ (perpetuo quasi fluvio).10 Regional traffickers may have been displaced from the southwest Mediterranean and the Balearic Islands, but they quickly adapted by moving farther eastwards towards Numidia. Now operating deeper inside the Empire, regional slavers turned from trafficking victims from outside the Empire to trafficking Roman citizens themselves. In effect, the Roman Empire’s slave trade had begun to cannibalize its own citizens instead of feeding on others from beyond the frontier.11 In his letter, Augustine observed with alarm the innumerable crowds of enslaved Africans waiting in the port of Hippo to be transported into the trade networks of the Empire. He gave a detailed account of the organization and violence inherent in human traff icking by describing how the demand of long-distance traffickers encouraged local suppliers. He writes,

There are so many of those in Africa who are commonly called, ‘slave dealers’ [mangones], that they seem to be draining Africa of much of its human population and transferring their ‘merchandise’ to the provinces across the [Mediterranean] sea […] Now from this bunch of merchants has grown up a multitude of pillaging and corrupting ‘dealers’ so that in herds, shouting in frightening military or barbarian attire, they invade sparsely populated and remote rural areas and they violently carry off those whom they would sell to these merchants.12

Regional and long-distance traffickers here played a pivotal role in supplying the Roman slave trade with bodies, by acting as middlemen who purchased these bodies from local raiders and then transported those victims to slave markets across the Empire, with a commensurate increase in price.13 More importantly, from a structural perspective, long-distance and regional trafficking networks depended upon (and thus inspired and encouraged) the activities of ‘homegrown’ sets of local traffickers, who used their local knowledge to determine the most vulnerable populations for abduction and exploitation. Local traffickers – those responsible for the actual home invasions and abductions – then sold their victims to regional and long-distance traders on the shores of the Mediterranean in ports such as Hippo. Augustine recognized the violent dynamics of supply and demand among local, regional, and long-distance traffickers, and he contended that regional and long-distance slavers from across the Empire created a demand for bodies that local traffickers then supplied by committing acts of aggression on isolated free peoples: ‘If there were not traders such as these [regional and long-distance traffickers], things like this [kidnapping, home invasion, and murder] would not be done. I don’t believe in the least that this evil that goes on in Africa is entirely unknown where you [Alypius] are.’14

Although trafficking networks increasingly relied on illegally abducted Roman citizens to supply the demand for slave labor in the late fourth and fifth centuries, regional traffickers continued to funnel human beings who were captured on the frontiers and in areas of instability into the more stable interior of the Empire. In order to expedite the sale of their victims, regional and long-distance traffickers worked in partnerships with local agents in provincial markets, who were more knowledgeable about the immediate political and economic conditions, the local demand for slaves, as well as the potential local supplies of slaves. These agents were thus well positioned to distribute their partners’ human cargo among vendors, buyers, and markets before the slave ships even arrived in port.15

Regional trafficking networks linked together in order to move slaves captured on the borders of the Empire into its vast web of regional and long-distance trade networks, which were linked by markets at Constantinople, Delos, Ephesus, Puteoli, and of course Rome itself.16 Ammianus Marcellinus (c. 330–395) reported that the Galatians were a major group of regional slavers on the northern borders of the Empire, operating along border-crossing zones between the Empire and Thrace. He writes that during the reign of Julian (r. 361–363), ‘Galatian merchants were equal to the Goths, by whom they were sold everywhere with no regard for their condition.’17 Augustine later named them as major players in the long-distance networks operating from North Africa.18 The Galatians were not the only regional and long-distance traffickers in the later Empire, however: as Ammianus records, in 372 a Roman officer under the Emperor Valentinian happened upon unidentified traffickers in Germanic territory, across the River Rhine. According to Ammianus, ‘because he [the officer] did not trust the guards [the traffickers] he happened to find there leading slaves to sale, who might quickly flee to report what they had seen, he, having seized their merchandise [the slaves], slaughtered them all.’19

Although numerous examples of regional and long-distance trafficking can be found in annals, sermons, and letters, local trafficking also features abundantly in transactions preserved on papyri across the Mediterranean basin. Widespread ownership of slaves, as well as natural reproduction, meant that owners did not necessarily need a middleman to find or to sell people, but could instead engage in direct transactions with other parties as household needs changed over time.20 Direct sale and exchange were so common within local urban economies or within wealthy social circles in the Empire that all extant sales records were transfers of one or a few slaves by private owners; slave traders are barely visible in the papyri.21 A middleman was unnecessary when slaves were born directly into households.

The Role of the Imperial Authorities

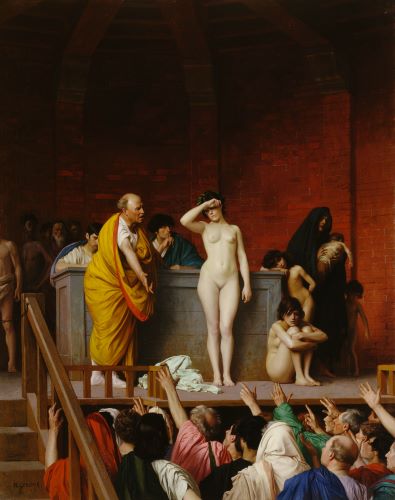

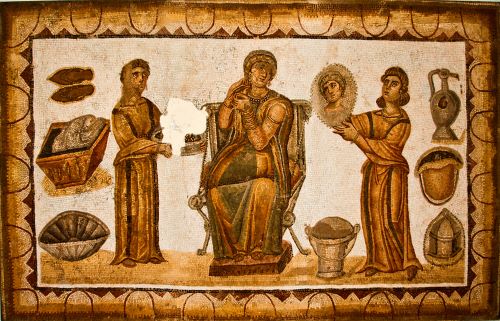

Human traffickers may operate within strong centralized states or politically unstable areas. A strong centralized state may actively aid traffickers through state-sanctioned social, legal, and commercial structures. For example, like the wine markets of Ostia, the slave markets of Rome had their own protective spirit; the Roman state religion recognized the genius venalicii, the spirit of the slave dealer to whom vendors made regular dedications, which gave the markets legitimacy through divine sanction. Religious festivals were prime opportunities to purchase slaves. Cassiodorus (490–585) remarked that during the Leukothea festival in southern Italy, the countryside became like a city because of the number of boys and girls of all ages who were for sale.22

The Edict of the Aediles, mentioned in extant sales contracts of the period, regulated the slave markets by stipulating information that the vendor was required to provide the buyer prior to purchase, protected the buyer against potential fraud, and set the conditions for return policies for purchased slaves.23 Financial institutions, such as the state bank of Rhodes, directly sponsored slave auctions or operated in conjunction with them, and offered credit and debit services for vendors and buyers who held accounts with the bank. For example, a papyrus document in the Oxyrhinchus collection details the sale of a North African girl by a certain Aurelius Quintus of Caesarea, in a slave auction at Rhodes sponsored by the bank. Kyle Harper interprets the document as evidence of institutional financial support of long-distance trafficking networks. In his view, Quintus is a trafficker from Mauritanian Caesarea who sold the girl at Rhodes, an important slave market in the Eastern Mediterranean. An Egyptian slave dealer bought the girl in Rhodes, and then sold her in Egypt.24 The state further legitimized the sale of human beings through a system of panels made up of minor bureaucrats who certified a person’s enslaved status and helped the new owner complete the paperwork necessary to finalize ownership.25

Particularly in cases where a centralized government encourages trafficking, or where local officials are corrupt, or in areas of political instability and decentralization, human trafficking flourishes. Rather than attempt to quash trafficking, Rome sought to regulate it and ensure that legally free Romans were not caught up in trade.26 However, as Moses I. Finley, Jacques Ramin, and Paul Veyne have all noted, there is a profound difference between regulations in theory and in practice. Corruption and poor access to the legal system helped insulate the trade from legal repercussions by ensuring that, once enslaved, the victims had little recourse to remedy their plight.27 For example, the slave himself, rather than an advocate for the slave, had to file suit in the case of wrongful enslavement, otherwise the state would not intervene; yet gaining access to the legal system and avoiding the wrath of the owner made legal relief for the enslaved difficult to obtain.28 Moreover, there was a layer of insulation between the illegal sources of slavery (such as the abduction of free citizens) and the slaveholder who purchased the slave. The slave trader acted as a middleman and was technically at fault, if the purchaser had made the transaction in good faith.29

However, bringing charges against slave traders who operated across the Empire was challenging, because even when the state acted to regulate the trade, its success ebbed and flowed with the political fortunes of the imperial authorities. For example, Augustine waxed nostalgic about the ability of imperial efforts to curb illegal trafficking networks in earlier times. ‘It was infinitely less serious earlier, when Emperor Honorius sent a decree to Prefect Hadrian, repressing traffic of this sort [the abduction and sale of free persons into slavery], sentencing such wicked ‘businessmen’ to be flogged with leaden thongs, proscribed, and sent into perpetual exile.’30 ‘Less serious’ is a relative term, and trafficking had been a problem even at the height of imperial power, but as centralized control over the Empire weakened, the effort to regulate traffickers became ever more dependent upon local officials who, because of their local roots and connections, were likely to know local traffickers and were thus susceptible to bribery, if they did not participate in the trade themselves. Augustine observed that the political conditions surrounding the regulation of human trafficking had deteriorated and that widespread corruption among local officials necessitated episcopal intervention to combat the slave trade. He continues in his letter to Alypius, ‘Now, if we do nothing for them [trafficking victims], who can easily be found (if he has some authority in coastal areas) who does not sell them more advantageously for the cruelest sea voyages, rather than take even one of these unfortunates off a ship or even not allow them to be put on a ship in the first place?’31 He then describes a clash of competing interests that resulted when local prelates intervened to protect their congregations from traffickers by jointly issuing a letter to the slavers, ordering a cessation of their activities against members of the Church of Hippo. Episcopal authority without firm imperial backing meant little, however, and the slavers apparently had their own official support from local administrative officials. Faced with intransigence among local slavers and corrupt officials, the Church of Hippo then organized a vigilante raid and freed 120 slaves in the immediate environs of the city. However, the slavers immediately counterattacked to recapture their chattel. Augustine writes,

For these Galatians do not lack advocates, with whose support they demand back from us those whom the Lord has freed, restored through the action of the Church, even those already restored to their own families who had been seeking them and who came to us with letters from bishops […] Despite the fact that a letter has come from an authority whom they should fear [i.e. episcopal authority], they have in no way halted their efforts to retrieve their captives.32

Official corruption was a problem across the Empire, not just in Numidia. In a panegyric to Emperor Valens (364–378) delivered before the Senate, Themistius (c. 317–388) observed that along the Danube, ‘The Goths could see that our fort commanders and garrison leaders were actually merchants and slave dealers, since this is essentially their only occupation, to buy and sell as much as they could.’33 In the aforementioned accounts of Ammianus Marcellinus we may recall that, according to the author, Roman generals were responsible for the deal in which Goth children were exchanged for dog meat, and that Julian’s officer assumed custody of the murdered traffickers’ captives. Whether these Roman officers were actually guilty of the charges Ammianus puts forth is not as important as the fact that this sort of local corruption was apparently so endemic that such behavior was considered perfectly believable by the author and his audience.

Rome never managed to exert complete control over all areas of its empire at any one time, and the danger of abduction was ever-present. Nearly all of the individual slaves whose origins are specified in literary or epigraphical sources were either from Italy or from provinces within the Empire.34 The Greek words for ‘kidnapper’ and ‘slave trader’ are semantically equivalent,35 and Church fathers railed against slave traders who lured children away with sweets and dice games, a constant worry of vigilant fathers. Athanasius (d. 373) observed that slavers waited for parents to leave their children alone in order to snatch them away.36 Augustine feared for runaway children who fled their parents in anger only to fall into the hands of slave traders, as well as for isolated village communities whose men were murdered in slavers’ search for women and children.37 While the language was meant to be rhetorical and proverbial, it nevertheless spoke clearly to the anxiety of the age, or such rhetoric would have failed to sway parental behavior.38

However, if the dangers of abduction were real and immediate within the Empire, the scale of the sale of children and infants is nevertheless difficult to determine since such activities have left little evidence in the extant records. Romans viewed the sale of children as barbaric, a crime against decency that demarcated Roman civilization from the ‘barbarian other’ beyond the frontiers. Nevertheless, Roman rescripts demonstrate that the sale of children within the Empire did in fact produce court cases, even if Roman literary references regarding the sale of youths appear to be indictments against foreign peoples in general, as opposed to concrete individual cases. As John Boswell has observed, there was an inherent tension between official imperial policy, which refused to allow for the reduction of free Romans into slavery, and the reality that parents could and did sell their children into servitude as circumstances dictated.39 As time went on, in the fourth century a growing focus on the plight of the poor by prominent Christians such as John Chrysostom, Augustine, and Cyril of Alexandria thrust the sale of children into the public discourse.40 In sermons and letters from this period, some culprits were Roman parents rather than barbarians. As Augustine observed, ‘Only a few are found to have been sold by their parents and these people buy them, not as Roman laws permit, as indentured servants for a period of 25 years, but in fact they buy them as slaves and sell them across the sea as slaves.’41 Roman law seems to have followed public concern over the practice of child sale, but it struggled to accommodate the practice in the legal structures of the Empire.42

From Centralization to Decentralization

Long-distance trafficking may have flourished in the first decades of the fifth century, but the annona shipments, the lynchpin for long-distance trade that also facilitated long-distance human trafficking, could only be maintained as long as Rome perpetuated its hegemony over the Mediterranean Sea and its surrounding provinces. Long-distance patterns of trade were already shifting gradually in the fourth and fifth centuries as the legions regionalized in the West and were increasingly supplied from their own hinterlands.43 The first blow to pan-Mediterranean commerce came in 439 CE with the Vandal conquest of Carthage in North Africa. From then on, the annonashipments to Rome ceased,44 but while the overall intensity of trade appears to dwindle over the course of the fifth and sixth centuries, by the end of the fifth century African wares were again growing in proportion to Eastern wares in excavation sites such as the port of Marseilles.45 North Africa seems to have re-established trade connections across the Western Mediterranean, even if the volume of that trade had diminished over the course of Vandal rule. Consequently, we may say that although the engine of long-distance trade in the Western Mediterranean was cut in 439, long-distance trade across the Mediterranean continued to coast for two centuries thereafter, a testament to the endurance of the trade routes the Empire had established and perpetuated.

For the city of Rome, however, this century – between Carthage falling to the Vandals and Carthage subsequently falling again to Justinian’s forces in 533– witnessed the continuing depopulation of the Eternal City. Economically, the West was characterized by growing regionalization of commercial activity. Long-distance trade still occurred in the former western provinces of the Empire, but more and more frequently such activity now involved a relay of merchants operating within interlinking commercial zones. The earlier age of exchange involving massive, centralized, and regularized shipments of goods between major ports across the Mediterranean was over. Long-distance trade moved one way: from east to west. Yet local and regional traffic within the Western Mediterranean, which connected smaller centers of consumption and production and had never disappeared even at the height of Roman imperial power, continued; the importance of this traffic intensified as long-distance trade with the Eastern Mediterranean abated, as demonstrated by the increasing amount of local and regional pottery wares present in the archaeological record of the sixth and seventh centuries.

With the demise of Roman political hegemony in the West, the socioeconomic contours of change broadly follow a pattern of decentralization. The economic integration of the peripheral Western Roman provinces and the Mediterranean, as well as the widespread use of common currencies and a uniform law code, were all lost over the course of the late fifth and sixth centuries.46 The volume and geographical scale of trade, state-subsidized movements of goods, and taxation all contracted and regionalized. This regionalization affected different areas in different ways but, broadly speaking, areas most closely tied into the Mediterranean economy were most affected, with the major exception being southern Italy, which was still tied into the trade routes of Byzantium. Areas that were less tied into the Mediterranean world were less affected, thanks to localized exchange networks that had remained integral to local economic life. However, there were major exceptions: these included inland Iberia (outside of Byzantine control) and Britain, where the collapse of Roman culture was swift and nearly complete.47

This understanding of the Roman economic trajectory from integration and centralization to regionalization and decentralization is key to understanding human trafficking networks during the transition from Late Antiquity to the early Middle Ages. With decentralization and regionalization, the rates of consumption and market production had diminished, and as they went so, too, did the Roman slave system. Endemic warfare meant that enslaved peoples still periodically flooded the markets, even as political instability weakened the very economy that created the demand for slave labor in the first place, and this led to crashes in prices. Writing after an attempted coup by Goth foederati, Synesius of Cyrene (c. 370–413) expressed his fear of Roman dependency upon Goth slaves and the danger of revolt in Constantinople and in the provinces. ‘Every house, however humble, has a Scythian [Goth] for slave. The butler, the cook, the water-carrier, all are Scythians, and as to retinue, the slaves who bend under the burden of the low couches on their shoulders that their masters may recline in the streets, these are all Scythians also.’48 Rhetorical embellishment and Synesius’ intense personal disdain for the Goths aside, the passage nevertheless suggests that upheaval along the frontier had created a buyer’s market for Goth slaves by the beginning of the fifth century. Herwig Wolfram makes a similar observation about the state of the slave market following the 406 defeat of the rebel Radagaius, a Goth and aspiring king, by the Roman general Flavius Stilicho (d. 408). He writes, ‘When the captured Radagaius Goths were sold into slavery, the slave market collapsed.’49 Simply put, the supply of slaves overwhelmed the demand for bodies and the ability of the market to absorb such a sudden glut. This dynamic only intensified over the course of the fifth century as the increasing political instability decreased the demand for slaves, since ‘both the consumption power of the middling classes and the elite’s ability to control market-oriented production were eroded in the early medieval world in which there was far less exchange.’ Thus the political and economic conditions changed across the Roman Empire over the course of the fifth century to such an extent that the fourth and early fifth centuries represents the last phase of a politically united and economically integrated Mediterranean.50

The Post-Roman West: Britain in the Sixth through the Eighth Centuries

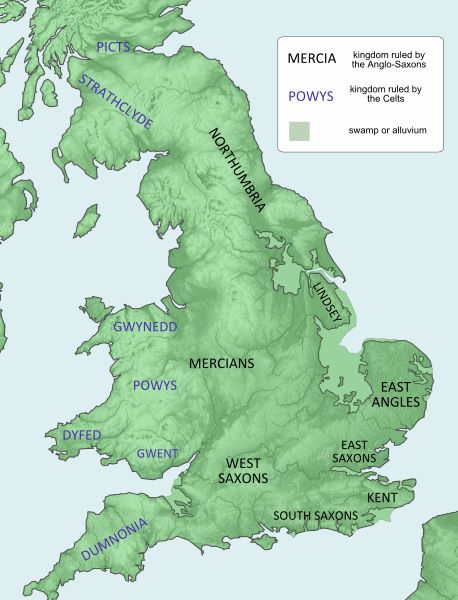

With the exception perhaps of inland Iberia, no region of the Roman Empire in the West appears to have suffered as swift and as complete a collapse of Roman culture as Britain. Within the span of 60 years, from the 360s to the 420s, Roman life in the province disintegrated. Britain had a modest production economy and organized industry under the Empire, but its economic vitality was founded upon mass commercial exchange of low-value agricultural and manufactured goods. This exchange was only viable so long as there was a dense network of small towns that provided access to wider imperial trade networks through their local markets.

As it happened, a series of internal political disasters (themselves tied into larger imperial political upheavals) befell the province at the same time as pressure from external raids and incursions was increasing. The combination of internal and external pressures fractured the political peace and stability of the province in the latter half of the fourth century and required more resources to repair than either Britain or the Empire could afford.51 Robin Fleming argues that at some point in the 360s or early 370s, the gradual socioeconomic erosion of Britain – ongoing since the 340s – passed a tipping point. Roman social and economic life unraveled completely before the end of the 420s. The household economies of Roman villas began to collapse the 360s; urban life disappeared, towns and villages ceased to exist in the early decades of the fifth century.52 Old Roman fortifications and Bronze and Iron Age earthenwork structures were reoccupied; cities and towns of stone and tile withered, while small villages of timber houses with packed earthen floors grew at the junctions of overland local and regional trade routes, as well as at the confluences and fording points of major rivers and streams.53 As in the Mediterranean basin, in Britain, too, herders and their animals had already established these overland routes long before the Romans had arrived, and in some cases these became the main arteries of transport and communications and remained in use for centuries.54 The arrival of the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes into England was clearly not the cause of Britain’s collapse, and their settlement was marked by local warfare in some areas, cooperation and assimilation in other areas, and by reoccupation of abandoned lands in still other places.55

Regional and Long-Distance Trafficking Networks in Britain

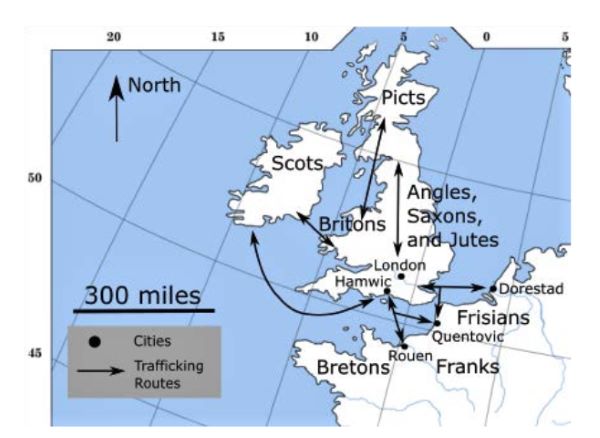

The late fifth and sixth centuries are almost devoid of sources for Britain, but not entirely: we may yet glimpse some activity regarding regional trade and, in turn, regional human trafficking. For example, in the latter half of the sixth century, Germanus of Paris (c. 496–576) attempted to redeem enslaved Picts (among others) in France, indicating that cross-channel trafficking had not disappeared even as Britain’s links with other former Roman provinces withered.56

Similar details of regional trafficking across the English Channel emerge in the mid-sixth-century De Exicidio Britanniae, roughly contemporary with the life of Germanus of Paris. Authored by the monk Gildas (c. 500–570), probably in the 540s, it describes the coming of the pagan Angles and Saxons and their conflicts with the native Britons. De Excidio Britanniae is a scath-ing polemic against the native Britons: Gildas repeatedly accuses them of forsaking their Christian faith, to the ruin of their island at the hands of the pagans, who by the 540s were expanding into Roman Briton territory once more after a period of relative peace in the early sixth century. He writes,

Some [Britons], therefore, of the miserable remnant, being taken in the mountains, were murdered in great numbers; others, constrained by famine, came and yielded themselves to be slaves for ever to their foes, running the risk of being instantly slain, which truly was the greatest favor that could be offered them: some others passed beyond the seas with loud lamentations instead of the voice of exhortation.57

Although Gildas was mainly concerned with demonstrating the punishments of neglecting one’s Christian faith, as a warning to readers in his own day (particularly as greater numbers of Angles and Saxons settled in Britain), nevertheless the picture of peoples being carried off into captivity ‘beyond the seas’ is certainly plausible. Saxon raiders had repeatedly attacked Roman Britain in the late fourth century, and they had been harrying its coasts and taking captives since the fifth century, as Sidonius Apollinarius (d. 489) makes clear in his letter to Namatius, a Gallo-Roman naval officer under the Visigothic King Euric (d. 484).58 We may presume that travel – and thus trade – between settlers in Britain and their kinship networks in northern Germany and Denmark had remained constant enough for news of current events in Britain to return to those areas and encourage further emigration to the island.

Only 50 years after Gildas wrote, the Angles themselves had become victims of cross-channel trafficking networks between Britain and the Continent, possibly via Bordeaux, Quentovic, or Frisia.59 In a letter dated to September 595, Pope Gregory I (r. 590–604) instructed his representative, a priest named Candidus, to buy Angle boys (pueri Angli) who were for sale in southern Gaul.60 David Pelteret suspects the likely market was Marseilles, which was still an important commercial center for the slave trade.61 Regardless of where the boys were sold, Gregory’s letter confirms that knowledge of Angle slaves available for purchase deep within the Continent had reached as far as Rome by the end of the sixth century. Moreover, the traffic in Angle youths within southern Gaul was apparently so consistent that not only could word of it reach Rome, but also that Gregory could reasonably assume that his representative would be able to journey to the slave markets after having received his letter and would still be able to find some children available for purchase. Furthermore, this letter allows us to view the famous anecdote of Gregory in the Roman slave markets as more than just a whimsical tale spun by Bede (c. 672–735).62 The story itself may be apocryphal, but the pope was nonetheless aware that Angle children were being trafficked into Mediterranean markets. These few scraps of information available to us for the fifth and sixth centuries, paltry although they are, nevertheless indicate that regional human trafficking networks between Britain and the Continent were not ad hoc exchanges occurring as chance dictated. Instead, they were a part of regular cultural and economic cross-channel exchange taking place by the middle of the sixth century.63

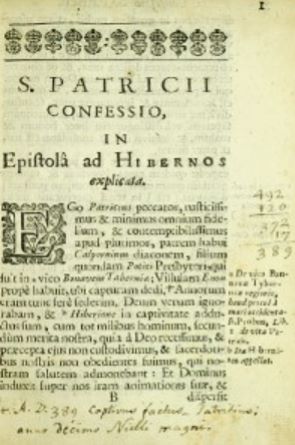

In the late fifth century and throughout the sixth, insular trafficking networks appeared to have run north into Pict territory and west across the Irish Sea, as Adomnan of Iona (c. 628–704) relates much later in his seventh-century Life of Saint Columba.64 The early life of Saint Patrick (died c. 460) sheds light on these insular trafficking networks. Patrick tells us in his Confessio of his capture in Britain by Irish raiders in the early fifth century:

My name is Patrick […] My father was Calpurnius. He was a deacon; his father was Potitus, a priest, who lived at Bannavem Taburniae. His home was near there, and that is where I was taken prisoner. I was about sixteen at the time […] I was taken into captivity in Ireland, along with thousands of others […] The Lord brought his strong anger upon us and scattered us among many nations even to the ends of the earth. It was among foreigners that it was seen how little I was.65

Muirchu’s Vita sancti Patricii, a seventh-century hagiographical work based upon Patrick’s Confessio, gives further details of the slave trade between Ireland and England. The vita likely reflects more accurately the reality of Muirchu’s own century than that of the fifth, but generally Muirchu follows the contours of the Confessio while emphasizing the religious divides within society that promoted mass enslavement and trafficking:

Patrick, also named Sochet, a Briton by race, was born in Britain. His father was Cualfarnus, a deacon, the son (as Patrick himself says) of a priest, Potitus, who hailed from Bannauem Thaburniae, a place not far from our sea […] As a boy of sixteen he was taken captive together with others, was brought to this barbarian island, and was held in servitude by a harsh pagan king […] After many hardships that he endured in that country[…] he left the pagan ruler […] and […] at the age of 23, sailed in the ship that was awaiting him, together with strangers – aliens and pagans, who worshipped many false gods – to Britain.66

The Confessio of Patrick and his later seventh-century vita provide a fair amount of information about insular trafficking patterns. We know that Patrick grew up near the old Roman road known as Watling Street, and his community was therefore vulnerable to domestic and foreign raiders, who do not appear to have operated in isolation among the Isles of Britain and Ireland. Roman transportation arteries allowed traffickers to strike inland communities quickly and move their captives to the shore with ease. The passage, ‘The Lord brought his strong anger upon us, and scattered us among many nations even to the ends of the earth. It was among foreigners that it was seen how little I was,’ suggests that these seaborne raids were part of much larger regional trafficking webs across northwest Europe.

As a teenager, Patrick was a prime target for raiders because he could fetch a high price; slaveholders could put adolescents immediately to work, unlike children who had to be raised to a certain age before their labor could turn a profit. Patrick was part of a large group of individuals who had been acquired by the raiders, but we do not know if these others were captured in the same raid as Patrick or in previous raids during the same expedition, or if the raiders had purchased them from former owners or other dealers. Nevertheless, the fact that there were several large groups of captives indicates that Patrick’s capture was a part of wider patterns of mass abduction. We may reasonably conclude that the demand for slave labor was great enough in Ireland and elsewhere to absorb groups of people periodically flooding the market. During his escape six years later, Patrick was able to find passage back across to Britain along with many other ‘aliens’ and ‘strangers,’ suggesting that insular commerce was widespread and regular; overall then, Patrick’s experiences do not appear in any way extraordinary.

The fact that the vita mentions ‘aliens’ and ‘pagans’ in the same breath suggests that the religious divide was a major fault line in seventh-century insular society and helped define the ‘other’ for the purposes of enslavement. Yet the religious divide was not insurmountable when it came to enslavement, because Christian religious identity was not strong enough to create a sense of taboo in enslaving members of one’s own community of faith. Patrick himself gives us evidence for Christians trafficking fellow Christians between Wales and the Picts in a harshly worded letter to a Romano-British king named Coroticus, who had allowed his Christian subjects to raid the coasts of Ireland and to then sell captured and newly baptized coreligionists to the Picts. As for the enslaved Irish Christians, the men were destined for hard labor and the women for sexual exploitation as well as for labor.67 Moreover, by demonstrating the differences in perceived religious solidarity between the Isles and the Continent, Patrick also demonstrates, through his knowledge of continental trafficking activity and ecclesiastical redemption efforts, that the Isles were by no means isolated from trafficking networks on the Continent. He writes, ‘The Roman Christians in Gaul behave quite differently [than you, Coroticus]: it is their custom to send holy, capable men to the Franks and other nations with several thousand solidi to redeem Christian prisoners.’68

By the seventh century, the beginnings of urban development were under-way in Britain, after a century and a half of absence. London, Hamwic (part of modern-day Southampton), Ipswich, and York show evidence of expanding populations, year-round craft and artisan production, regional trade, and the presence of foreign merchants in both written and archaeological records.69 It is also in the middle of the seventh century that regional human trafficking networks become increasingly clear. Bede tells us that during the conversions of the Anglo-Saxons, Bishop Aidan (d. 651) used the wealth he received from pious donations to ‘ransom any who had been unjustly sold into slavery,’ whom he met in his wandering throughout northern and central England.70 The ransoming of slaves is a trope in medieval hagiography, and as such, this behavior was expected of saints by their cults. Nevertheless, the fact that these manumissions occurred as Aidan wandered England suggests that the slave trade as well as both barter and monetary exchange were all widespread across Anglo-Saxon England, since Aidan ransomed captives using the wealth he had received as pious donations from patrons.

In one of his most famous passages, Bede relates that in 679, during a battle between Ecfrith of Northumbria (r. 664–685) and Elfwin of Mercia, Imma, a young thane under Elfwin, was struck in the melee and, falling unconscious, was mistaken for the dead upon the battlefield. After he had regained consciousness and then his strength, he sought out his allies but was discovered by the Northumbrian forces and taken prisoner by one of their nobles. When the Northumbrian discovered that Imma was in fact a thane and a noble of Elfwin, he then sold him to a Frisian merchant in London.71 This story yields some detail of regional trafficking during the late seventh century in England. We can discern that London was already not just an important administrative and economic center, but also a hub of regional slave trading between England and the Continent. The fact that a Northumbrian was aware of foreign merchants in London and opted to bring Imma there, as opposed to York, suggests that London had apparently already acquired a reputation within the Heptarchy as a trading center, and as a town in which this young noble captive’s full value in currency and in kind might be obtained.72

Let us turn from London to Hamwic in Sussex, another center for trade and trafficking in seventh-century England. Bede relates that after Bishop Wilfrid (c. 634–709) had received a substantial holding of land in Selsey from King Aethelwalh of Sussex, sometime in the 660s, the bishop manumitted 250 men and women from slavery: ‘Wilfrid instructed and baptized them all in the Faith of Christ. Among them were 250 male and female slaves, all of whom he released from the slavery of Satan by baptism, and by granting their freedom, released them from the yoke of human slavery as well.’73 Selsey is on the southern shores of England, approximately 40 miles to the southeast of modern-day Southampton (known as Hamwic in the seventh century), and is known from archaeological records to have been an important and growing emporium for regional trade and craft production.74 It is not certain that the slaves manumitted by Wilfrid were chattel slaves bought in Hamwic’s market, nor is it certain, in fact, that 250 slaves were even to be found in the area of Selsey. Nevertheless, we should not be surprised to find a relatively large number of slaves within several days’ travel of one of the four most important ports of seventh-century Anglo-Saxon England.

The growth of Hamwic as a center for regional trade had important socioeconomic consequences for those who lived in its hinterlands, since the inhabitants of the surrounding area had convenient access to the emporium’s market and hence to regional trade and trafficking routes, which thus encouraged local human trafficking activities. For example, according to Stephanus, the hagiographer of Bishop Wilfrid, the bishop was blown off course during a storm as he left Gaul on his way to visit the Archbishop of York. When they were beached by the waves, they found themselves in Sussex, where the local inhabitants attacked the bishop and his party, ‘intending to seize the vessel, loot it, carry off captives, and slay without more ado all who resisted.’75 Through divine intervention, the bishop and his party were saved and eventually made their way back to Sandwich in Kent.

From Continental sources, we f ind corroborating evidence for brisk seventh-century regional trade and trafficking. The importance of Frisian merchants as middlemen and traders appears in two letters sent from Pope Gregory I in 599 to Queen Brunichild (r. 575–613) and to the Merovingian kings Theuderic II (r. 587–613) and Theudebert II (586–612).76 Amandus (c. 584–675), a missionary bishop from the region of Anjou, reportedly ‘redeemed captives and even youths from across the sea’ in the course of his work in Frisia; we may assume these captives were from England because of the proximity and close socioeconomic and cultural exchange between the two regions.77 There is reference, furthermore, to slavery among the Frisians themselves. The ninth-century Miracula Sancti Goaris, authored by the monk Wandalbert of Prüm, contains a scene in which slaves pull the boat of a Frisian merchant upstream along the Rhine from its banks.78 More concretely, the Frisian law code specifically addresses the export of human beings from Frisia (extra patria vendere): ‘If someone sells a man abroad, whether a noble man selling a noble man or freeman, or a freeman a freeman, or a freeman a noble man, he pays for him, as if he had killed him, or he must attempt to get him back from his exile.’79

The aforementioned Frankish queen, Balthild, an Anglo-Saxon ‘from lands across the seas’ (de partibus transmarinis), had been sold to Erchinoald, Mayor of the Palace of Neustria, before she was given as a gift from Erchi-noald to King Clovis II.80 The Frankish Bishop of Noyon, Eligius (588–660), according to his biographer, Dado, the Bishop of Rouen (c. 610–684), made it a point to purchase and free slaves he found in Neustria, and native Britons were included among the diverse lot to be found for sale there.81 Dado’s biography sheds light on the extent of human trafficking activity in seventh-century Merovingian Francia, which will be explored in the next section. He writes, ‘He [Eligius] freed all alike, Romans certainly, Gauls and also Britons, as well as Moors, but especially Saxons who were as numerous as sheep at that time, expelled from their own land and scattered everywhere.’82

Exchange assumes two-way traffic, and indeed we find evidence for slaves from the Continent for sale in English markets in the seventh century. For example, in the first half of century, Richarius (d. 645) attempted to redeem Frankish captives when he was in England, and Filibert (d. 684), Abbot of Jumieges and Noirmoutier, sent monks from his monasteries to England to do likewise in the latter half.83

The Role of the Authorities in Britain

Anglo-Saxon law codes and the decrees of church councils promulgated in the late seventh and early eighth centuries began to confront the problem of human trafficking directly. The laws of Aethelbert (r. 560–616), written at the beginning of the seventh century, make no mention of kidnapping and sale, but by the last two decades of the century the laws of the kings of Kent and Wessex reference the ‘stealing’ of other human beings. For example, in the laws of Hlothere (d. 685) and Eadric (d. 686), kings of Kent, dated to between 673 and 685 roughly, subsection 5 stipulates that, ‘If a freeman steals a man, if the latter is able to return as informer, he is to accuse him to his face,’ at which point the trial proceedings could begin.84 The law does not tell us anything about whether the victim was sold or kept by the perpetrator, but the wording acknowledges the possibility of return, which suggests that the law was envisioned to cover circumstances involving distant transport and sale. The laws of Ine, King of Wessex (r. 688–726), drafted sometime between 688 and 694, specifically address abduction and cross-channel human trafficking in subsection 11: ‘If anyone sells his own countryman, bond or free, even if he is guilty, across the sea, he is to pay for him with his [own] wergild.’85 However, the law is quite limited in its scope. Although it specifically protects both legally free and unfree, it makes no mention of any foreign-born persons, an example of a general social taboo observed across societies against enslaving members of one’s own community, however that community is defined.

The Church in some instances encouraged human trafficking by using overseas trafficking networks as a means of maintaining law and order, or by intervening in the market in order to protect purchasers from fraud in the case of local trafficking. For example, the English Synod of Berkhampstead in 697 sanctioned transmarine trafficking in specific cases, decreeing that if a slave had been stolen, then his master, at the discretion of the king, was to either pay a fine of 70 solidi as compensation or else sell the slave beyond the sea.86 The ‘master’ in this context is the thief or the new owner of the slave, and the decree uses regional trafficking to punish the thief by depriving him of his new property.

In the seventh-century church councils of Wales, ecclesiastical officials set down regulations by which purchasers could return their slaves to the former masters. ‘If a man has bought a male or female slave, and within the year some unsoundness is found in them, we order the slave to be handed back to the former master; but if a year has elapsed, whatever defect may be found in the slave, the buyer has no claim.’87 Yet beyond regulating return policies of faulty merchandise, the Church rarely intervened in the slave trade except to protect the bonds of marriage. For example, if a man married his female slave and then later attempted to sell her, the woman was to come under the protection of the Church and the man faced eternal perdition.88

In these Welsh decrees the scope of the rulings is narrow and immediate. The regulations involving purchasers and former masters, or the sales of wives by husbands, refer primarily to small-scale local trafficking between parties that could easily be accomplished without a middleman such as a trader. The church councils made no claim to wider authority over regional trading, probably because enforcing return policies on transmarine traffickers would have been highly problematic in politically decentralized seventh-century Wales. Instead, the church councils, when they did intervene in the slave trade, did so at a level where they could reasonably expect their authority to be respected in the lands under their jurisdiction. These rules applied not to itinerant traders, but instead to local inhabitants of the communities under the authority of local prelates and their representatives.

Local Trafficking Networks

The decrees of seventh-century Welsh church councils provide an excellent opportunity to shift our focus from regional to local human trafficking within the islands. Local trafficking is generally more challenging to illuminate because of the fragmentary nature of early medieval sources. References to slave sales are scattered and laconic, and when they do appear, regional human trafficking is referenced most frequently. Slave origins are mentioned when the enslaved are foreigners, but not when they are local people. Nevertheless, we can glimpse trafficking activity, presumably local, from several of the examples previously mentioned. The gifting of island inhabitants after Wulf here’s raid on the Isle of Wight, noted in the Introduction, take on monetary implications when we consider the importance of Hamwic as a regional commercial hub. The inhabitants of the hinterlands of Hamwic attacked Wilfrid and his party intending to capture victims, presumably to enslave. While it is possible that, had the assailants been successful, they would have kept their victims as their own property, their proximity to Hamwic suggests that these local raiders had regional markets in mind. The wording of the law of Hlothere and Eadric suggests that a victim might be either kept or sold to buyers within the kingdom, and hence there was greater potential for the victim to return. In the case of Imma, the unfortunate Mercian youth was in the hands of a noble from neighboring Northumbria before he was sold to Frisian merchants in London.

These examples, tenuous although they are, suggest a couple of characteristics of local traffickers. First, many local traffickers in early medieval England do not appear as professionals but rather as opportunists who capture or abduct as circumstances permit, unlike the local traffickers Augustine observed, who meticulously planned their systematic mass abductions with the intention of supplying regional and long-distance traffickers in the port of Hippo. Nevertheless, even in medieval England I suspect that local trafficking in aggregate was brisk and steady enough to account for the volume of Anglo-Saxon slaves regularly available for purchase on the Continent. This hypothesis leads us to our second observation regarding the extended relationship between regional trade and trafficking networks and local traffickers: regional trade encouraged regional trafficking, and regional trafficking encouraged local trafficking, similar to Augustine’s observations of the attacks and abductions in the hinterlands of Hippo. At least some local slave raiders and traders in Anglo-Saxon England were aware of regional trade networks and actively sought to connect to those networks through contacts with established regional traffickers in the markets, as the stories of Bishop Wilfrid and Imma suggest.

The Post-Roman West: Continental Western Europe in the Sixth through the Eighth Centuries

Across Western Europe, the great river systems of the Rhône, Saone and Meuse, Rhine, and Danube bustled with traffic in the fourth and fifth centuries, and they served as transport arteries for commerce as much as physical barriers to invasion. These river systems connected with Roman road networks and together formed networks of communication, transportation, and trade that spanned the length and breadth of Western Europe, while farther east the Rhine and Danube connected the imperial centers at Cologne and Constantinople. Long-distance trade continued to move into and out of Western Europe through ports on the north shore of the Western Mediterranean, such as Arles and especially Marseilles, which connected with the fluvial and overland routes of the interior. Seated at the confluence of the Rhône and Saone river systems, Lyon was considered a port with ‘direct’ access to Mediterranean commercial networks. The Rhône was such an important artery for traffic that Arles was considered the port of landlocked Trier in the middle of the fourth century.89 Overland routes linked the Rhine to the Saone and Rhône river systems, which continued to supply Merovingian Gaul and Visigothic Septimania with a dwindling supply of goods from across the Mediterranean and simultaneously increased in importance as arteries for local and regional travel. For example, circa 471 Bishop Sidonius praised his fellow ecclesiastic, Patiens, Bishop of Lyon (475–491), for sending a substantial load of supplies down the Rhône to cities in Provence after the area’s trade networks had been disrupted by war. The Vita Caesarii describes the Burgundian kings doing likewise around 510.90 As time went on, however, river systems such as the Rhône and the Danube lost their importance as the territories through which they flowed became increasingly hostile. Peter Spufford and other scholars observe that the main axis of communications between Gaul and the Mediterranean shifted eastwards away from the Rhône and towards the Alps between the sixth and eighth centuries, and Bavaria and the Rhine gained in importance as Provence and the Rhône lost it.91

Beginning in the middle of the sixth century, overland routes between Western and Eastern Europe – particularly between Merovingian Francia and Constantinople – were disrupted, initially because of the Avars and later, in the seventh century, because of the Bulgars, both of whom occupied the middle and lower Danube regions and cut off access to Constantinople via land routes. In the Balkans, major thoroughfares such as the Via Egnatia fell out of use between 550 and 650, possibly because of Slavic settlement in the area. Although sea routes were still available to carry communications, goods, and people between the eastern and western portions of the former Roman Empire, the rapid closure of fluvial and overland transportation arteries nevertheless exacerbated the regionalization of the period.92

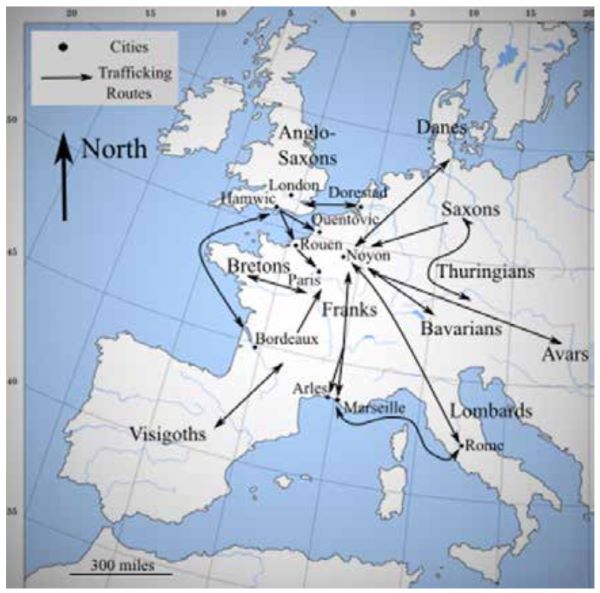

Regional Trafficking Networks

Endemic warfare on the Continent during the Merovingian and early Carolingian periods ensured the consistent traffic of human bodies in local and regional trade networks, and there has been a fair amount of research on the trade routes that human traffickers used.93 According to medieval authors, oftentimes the source of bodies came from the dramatic wholesale reduction of populations to captivity by conquering armies. Generally, mass enslavements that involved regional trafficking activity occurred in the border zones of major ethnic groups such as the Franks,94 Lombards,95 Aquitani,96 Danes,97 Bretons,98 Burgundians,99 Visigoths,100 and Avars101 in the sixth and seventh centuries, and later the Slavs and Muslims in the eighth.102 Yet what became of these people is difficult to say, because our sources often describe their capture in a litany of other tribulations including rapine, wholesale murder, the destruction of fields, and so on. Some of these victims of war were surely ransomed, but those who could not afford their ransom or who were unable to escape faced the prospect of enslavement for the foreseeable future. In a telling confrontation in the early 580s between King Childebert II (570–596) and the men mustered for his army from the ranks of the peasantry, the ‘lower ranks’ (minor populus) shouted (vociferare and proclamare) at the king to ‘dismiss those [the royal advisors] who are betraying his [Childebert’s] kingdom.’ They continued to shout, ‘Down with those who are handing his cities over to an enemy power! Down with those who are selling Childebert’s subjects into foreign slavery!’103 From these protests we can glimpse a likely future for many who could not afford to pay for their release, since the protesters were from the lower ranks of Childebert’s army: the very peasants who were most likely to suffer the fate of mass enslavement in the endemic warfare of the period, and who were acutely aware of their own vulnerability to depredation.

The mass enslavements described in narrative sources thus give us the context surrounding the passage in the seventh-century Life of Eligius, cited above and repeated here: ‘He [Eligius] freed all alike, Romans certainly, Gauls and also Britons, as well as Moors, but especially Saxons who were as numerous as sheep at that time.’104 While Britons and Anglo-Saxons, such as Balthild, were trafficked into Francia from the northwest, from the southeast came native Italians in the wake of the Lombard conquests. In 595, Pope Gregory I related to the Byzantine Emperor Maurice (r. 582–602) how the Lombards under Agiulf (r. 590–616) had enslaved natives in the environs of Rome to be transported to markets in Francia. He says that, after the arrival of Agiulf, ‘thus I saw with my own eyes Romans, bound with ropes around their necks like dogs, being led to sale in Francia.’105 Simply put, mass enslavement of different ethnic groups was an expected consequence of defeat in the chronic warfare in early medieval Western Europe.106

Long-Distance Trafficking Networks

Regional trafficking brought these enslaved groups of people into market towns like Noyon from across the ethnic and political divides of the region, yet Merovingian Francia by all accounts did not possess a strong enough economy to absorb all those enslaved. The remainder were trafficked, as William D. Phillips Jr. contends, along the broad contours of trade routes that passed from the borders that divided these ethnic groups and moved through Francia towards the Mediterranean basin via overland, river, and shoreline transportation networks. Marseilles was the most important nexus of the Western European slave trade in the sixth and seventh centuries due to its access to regional marine trade routes,107 which were probably the source for the Moorish slaves in the account of Eligius, and to fluvial routes that led into the interior of Merovingian Francia. Overland routes running north to south across the Merovingian heartland, through Arras and Tournai, also terminated in Marseilles.108 The life of Bishop Bonitus of Clermont (c. 623–710) demonstrates the central position of Marseilles in early medieval trafficking. Before his episcopal career, Bonitus had served as a royal Merovingian administrator for Marseilles and later all of Provence. According to his vita, ‘Men were being sold into exile as was the custom there [Marseilles], so he [Bonitus] condemned that this penalty ever be given, but rather those they could find who had been sold, as he had always been accustomed to do, he redeemed and sent them home.’109

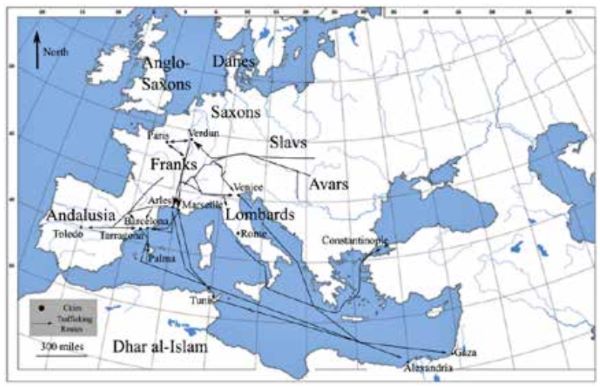

By the latter half of the eighth century, Frankish traffickers were expanding eastwards into Central Europe, once again following fluvial routes such as the Danube as well as overland routes that started in Slavic lands and ran west through Bavaria. In Bavaria, the routes forked. North and west, traffickers crossed Germany and entered France, following the river valleys of the Moselle and Meuse to Verdun, a slaving hub and a center for castration. From Verdun, traffickers moved their cargo down the river valleys of the Saone and the Rhône to Arles and Marseilles for shipment to Muslim North Africa, and to Iberia via transmarine or overland routes across the Pyrenees. In Iberia, slaves were imported and exported in markets in Barcelona, Tarragona, Palma, and Toledo, either for domestic labor or for resale farther into Muslim lands in North Africa and Egypt.110

The southern fork in Bavaria crossed the Alps at major passes that con-ducted trade through arteries such as the old Roman mule track connecting Lake Leman to the Great St. Bernard Pass, or the wagon route that crossed the Alps along the Little St. Bernard. Near the source of the Rhine in the Alps, another mule road ran over the Spulgen Pass (although it was an ancillary route in the eighth century), while wagon routes led to Italy via the Septimer and Julier–Maloja passes.111 Once across the Alps, trade routes again forked, turning south towards Rome and southeast towards Venice; the Venetians transported their captives by sea down the Adriatic towards Byzantium and the Muslim markets of the Levant, particularly to ports like Gaza and Alexandria. While Byzantium maintained some degree of control over the Italian coast of the Adriatic, emperors like Leo V (r. 813–820) were nevertheless unable to prevent the Venetians from trafficking people across the Mediterranean into the Abbasid Caliphate, the enemy of Constantinople.112

The Role of the Authorities in Continental Western Europe

In sixth-century Western Europe, the vulnerability of peasants to mass enslavement via conquest was exacerbated by the Merovingian kings’ need for political support. Captives were a recognized part of the spoils of war, and as such the promise of taking captives – and the wealth they represented in their bodies – served to secure the loyalty of a king’s retainers and retinues, which were the bases of his power.113 Authorities in sixth-century Merovingian Francia thus offered the promise of wholesale enslavement as a reward for steadfast loyalty and support, and they encouraged the practice among their retinues. For example, when Lothar I (c. 497–561) and Childebert I (c. 498–558) decided to attack the Burgundians, their brother Theuderic I (c. 487–534) declined their invitation, hoping instead to attack the inhabitants of Clermont-Ferrand, whom he suspected of treason. His men threatened to depose him if he declined the Burgundian campaign, unaware, as they were, of his ulterior motives. Theuderic is reported to have said to them, ‘Follow me, and I will lead you to a land [his own Clermont-Ferrand] where you will be able to lay your hands on so much gold and silver that even your lust for loot will be satisfied. If only you agree not to go off [into Burgundy] after my brothers, in this other land you may capture as many cattle and slaves and seize as much clothing as you wish.’ Theuderic succeeded in convincing his men to remain loyal to him, and on the border of Clermont-Ferrand he again reminded them that, ‘they had his permission to bring home with them not only every single thing they could steal in the entire region that they were about to attack, but also the entire population.’114 Such was the price of betrayal, real or imagined. The population of Clermont-Ferrand became the ‘other’ to Theuderic and thus fair game for mass enslavement, as well as a gift from the king to his retainers in order to secure their loyalty at a time when he felt vulnerable and threatened by the possibility of revolt.

Even if sixth-century rulers did not openly encourage mass abduction, at times they were powerless to stop the practice among their own men or their more powerful retainers. For example, during a particularly brutal period of civil war among Sigibert I (d. 575), Chilperic I (c. 539–584), and Theudebert I (d. 547), the armies of King Sigibert pillaged the Île de France despite his protestations, which resulted in the mass enslavement of the local peasant population.115 In a later period of war between Guntram (c. 532–593) and Chilperic I, Chilperic’s forces besieged Bourges and ‘stole so much booty that, as they evacuated it, the entire area seemed empty of inhabitants and cattle.’116 The patrician Mummolus attempted to carry off the inhabitants of Albi, but the bishop Salvius (r. 574–584) persuaded him to release them.117

As time went on, over the course of the seventh and eighth centuries, Western Europe became increasingly concerned about the sale of Christians to non-Christians.118 Christian religious identity appears to have taken on greater importance in relation to local or ethnic identities, at least within the upper echelons of society, but this transition did not represent a complete substitution of one identity for another, and local identity remained strong enough that successive church councils repeatedly found it necessary to issue decrees against the sale of Christians by Christians to heathens and Jews. There were, of course, periodic exceptions to this ecclesiastical trend. For example, the Fourth Council of Toledo in 633 reiterated earlier decrees that the concubine of a priest was to be enslaved and sold beyond the sea as a means of ensuring clerical discipline and morality,119 and we can cite the previously mentioned English synod of Berkhampstead in 697 as another notable exception. Nevertheless, over time the Church generally inclined towards regulating and restricting the sale of Christians by their coreligionists to members of other ethnic and religious groups. For example, the Tenth Council of Toledo in 656 decreed that Christian slaves were not to be sold to Jews, as part of the wider concern among late Visigothic rulers about the potential conversion of Christians to the Judaism of their masters.120 In Merovingian Francia, the Council of Chalons in 644 restricted the sale of Christians to the domestic market only and prohibited their sale beyond the dominions of Clovis II, in order to prevent the sale of Christians to Jewish owners.121 After the death of Clovis, Queen Balthild, acting as regent, reissued the council’s decree as a royal edict. According to her vita, ‘She [Balthild] forbade Christian men to become captives, and she issued precepts throughout each region that absolutely no one ought to transfer a captive Christian in the kingdom of the Neustrians.’122 The queen took the Council of Chalons edict a step further, clamping down on the enslavement of Christians in general by forbidding their sale within the kingdom as well, despite the impossibility of enforcement.

However, Balthild seems to be extraordinary among seventh-century authorities in her determination to suppress human trafficking. Most proclamations only prohibited the sale of Christians to non-Christians or to foreigners. Other rulers perpetuated human trafficking in order to enforce the social order, regardless of the victim’s religious identity. For example, under the Lex Rothari of 643, a body of Lombard laws promulgated by Balthild’s contemporary King Rothair (r. 636–652), a woman who had married her slave was to be enslaved herself by her family members, who were then allowed to kill her or sell her overseas with no regard for where or among whom she might be sold.123 Rothair used regional and long-distance human trafficking as a means to discourage interclass mixing among the Lombards, but he disregarded the fact that the woman in question was likely Christian and her sale overseas would potentially be among unbelievers.

Balthild may have been unique among seventh-century rulers, but by the middle of the eighth century the inclination towards regulation and restriction appears to have been more widely held among rulers and ecclesiastical officials than it had been earlier. For example, in 743 a church council at Liftina, presided over by Boniface (c. 675–754), decreed it unlawful for a trafficker to sell a Christian to the heathens, presumably the Slavs and Saxons.124 Pope Zacharias (r. 741–752) in 748 attempted to halt sale of Christians to unbelievers by banning the Venetian sale of Christians to North African Muslim slavers in the Roman slave markets, and by redeeming the captives there in Rome.125 By 772, the Duke of Bavaria, Tassilo III (r. 748–788), had decreed, with the endorsement of major prelates, that the sale of slaves beyond the boundaries of the province was henceforth illegal, regardless of whether the slave was purchased as property or had been taken during a flight from justice.126 Six years later in 778, Pope Hadrian I (r. 772–795) defended himself and the city of Rome against charges of selling Christian captives to Muslim slave traders in the Roman markets in a letter addressed to Charlemagne (742–814). The pope vigorously denied the allegations, but notably he did not deny that Christians in Italy were in fact being sold to Muslims. He instead placed the fault for such activities on the Byzantines, whom he claimed had made a treaty with the ruling Lombard families of northern and central Italy, and had thus procured their human cargo through these official connections.127 Charles himself forbade the sale overseas among pagans of those who had voluntarily sold themselves into slavery because of debt or poverty, and he found it necessary to explicitly emphasize the freedom of any of their family members in order to ensure that they were not also sold into slavery to cover the debts of their kin.128

The change in attitude among rulers over the course of the sixth to eighth centuries is noteworthy. In the sixth century, rulers such as Theuderic treated mass abduction as a matter of political expediency, to be used as a means of securing the loyalty of their armed retinues; in other cases, they were simply unable or unwilling to effectively ban the practice. By the middle of the eighth century, however, both rulers and ecclesiastical bodies generally sought to limit human trafficking, however minimally, rather than to encourage it for political gain, motivated as they were by a fear of losing coreligionists to conversion among the Muslims, Jews, and pagans.129 The process was slow, taking over two centuries, and as the Synod of Berkhampstead, the laws of Rothair, and the Visigothic Church councils all demonstrate, it was neither inexorable nor uniform.

Local Trafficking and the Authorities

If regional and long-distance trafficking came more and more under the scrutiny of secular and ecclesiastical authorities, local trafficking seems at best overlooked and at worst tolerated. Local trafficking took less dramatic forms than the wholesale enslavement of entire populations, and (as had been the case in the Late Roman Empire) it often did not require an intermediary, such as a slave trader, to facilitate the transaction. Local trafficking of abandoned children was apparently so consistent in northwestern Francia that it necessitated legal standardization. A sixth-century formulary from Anjou, written in the colloquial Latin of the day, regularizes the sale of abandoned children by their finders as well as the expected remuneration:

In the name of God. Whereas, I, brother _____ , one of the dependents of the parish of St. _____ , whom Almighty God sustains there through the offerings of Christians, found there a newborn infant, not yet named, and was unable to find relatives of his among any of the populace, it was agreed to and permitted by the priest _____ , that I could sell the child to _____ , which I have done. And I have received for him, as is our custom, a third plus food.130

Gregory of Tours (c. 538–594) relates that a certain young nobleman named Attalus, from the family of Bishop Gregory of Langres (c. 450–539), had been exchanged as a hostage to ensure peace between kings Childebert I and Theuderic I in the late 530s. When the peace failed, Attalus was enslaved and sent to Trier to groom horses. His family rescued their son and heir with the help of the family cook, a man named Leo, who allowed the family to sell him into slavery to the family who owned Attalus. Over the course of time, Leo earned his new master’s trust, and with the help of divine intervention, he was eventually able to escape with the boy.131

Even as attitudes towards regional trafficking changed over the course of the seventh and eighth centuries, local leaders did not address the problem of local trafficking within their own borders. They may not have openly encouraged such activity, but their silence implies a tacit acceptance of the practice, or at least of their inability to suppress it. Only the proclamation of Balthild appears to have targeted local trafficking activity in any way. Church councils and off icial edicts, such as that of Duke Tassilo in 772, only banned trafficking beyond religious or territorial boundaries, and did not address traffic within the borders of kingdoms or bishoprics. The sale of Christians to pagan and Jewish buyers was restricted, but the sale of unbelievers does not appear in any of the edicts, nor does the traffic of Christians among fellow Christians. I suggest that the primary reason why local trafficking remained outside the scope of ecclesiastical and royal decrees was not so much an oversight on the part of local and regional authorities as it was a lack of concern. In areas that were relatively Christianized, the dangers of Christians falling into the hands of unbelievers were minimal. The community of faith was threatened by the sale of enslaved coreligionists abroad, because it was impossible to ensure the victim would be purchased by a coreligionist, which thus presented the possibility of conversion to their new owner’s faith. Royal and ecclesiastical suppression efforts were motivated by concern over the losses of Christians to competing religions, not over the sales of human beings.