The regulation of technology in the medieval world was multifaceted.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The popular imagination often characterizes the Middle Ages as a period of technological stagnation and unregulated mysticism. Yet the medieval world was far from a technological vacuum. From the invention of mechanical clocks and improved plows to the expansion of water-powered mills and the refinement of metallurgical techniques, medieval Europe witnessed a variety of technological innovations. These developments did not occur in an unregulated vacuum. Rather, technological diffusion and usage were deeply embedded in social, religious, and political frameworks that exerted control through guild systems, feudal privileges, ecclesiastical decrees, and civic ordinances. Regulation in the medieval world was diffuse, localized, and often moral in character—but it was nonetheless real, exerting tangible influence on how and where technologies could be used, who could access them, and under what terms they could be shared or replicated.

Guilds and the Regulation of Technological Knowledge

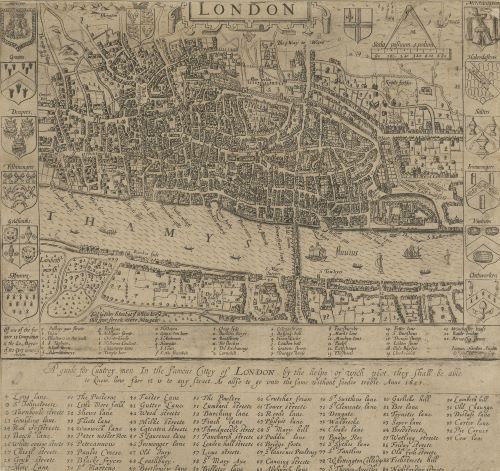

One of the most significant mechanisms for regulating technology in medieval Europe was the urban craft guild. Guilds emerged in increasing numbers between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries, particularly in growing urban centers such as Paris, Florence, and London. These associations of artisans and merchants controlled access to trades, dictated the terms of apprenticeship, and enforced standards of quality and conduct within their professions.

Regulation of technological knowledge was central to guild function. Mastery of tools, processes, and specialized materials was passed down through rigidly structured apprenticeship programs. Guilds could require up to seven years of apprenticeship before a craftsman could achieve journeyman status, followed by years of work under a master before being permitted to produce a “masterpiece” and apply for full membership.1 This process ensured not only the technical competence of artisans but also the containment of trade secrets. For example, glassblowing techniques in Venice were guarded so fiercely by the glassmakers’ guild of Murano that craftsmen were forbidden from emigrating, under penalty of death.2

Guilds also enforced technical standards in production. Tools had to conform to accepted models, weights and measures were often standardized, and deviations could result in fines or expulsion.3 Thus, guilds regulated both the dissemination and the operation of technological knowledge, forming a decentralized but effective system of quality control and innovation management.

Feudal Privileges and Manorial Monopolies

Beyond urban centers, technological regulation often rested in the hands of feudal lords and manorial authorities. Many critical technologies—especially those related to agriculture and processing—were tied to rights of ownership and obligation. Lords frequently held monopolies over the use of mills, wine presses, and ovens, and peasants were required to use these facilities for a fee.4 The widespread deployment of watermills during the High Middle Ages, for example, was deeply entangled with manorial privilege. Unauthorized construction of a mill could be considered a violation of the lord’s economic rights and be met with legal action or force.

This form of regulation was economic as well as territorial. Manorial lords derived income from their monopolistic control over essential technologies, and any technological development that threatened this income—such as a peasant installing a hand mill—was often suppressed.5 Such controls could extend even to land use: innovations like the heavy plow and the three-field system were sometimes regulated not by legal code but by customary law and communal agreements under the supervision of the manor court.

Ecclesiastical Regulation and the Moral Dimension

The Church exerted enormous influence over technological development and its limits, both as a landowner and as a moral authority. Monasteries were often sites of innovation, especially in the use of water power for grinding grain, tanning leather, and irrigating fields.6 But ecclesiastical approval could also constrain certain technological practices—particularly those seen as encroaching upon divine or moral boundaries.

Medical technologies such as dissection were intermittently banned or discouraged, depending on local interpretations of Canon law.7 Similarly, mechanical automata—like those crafted by engineers in Islamic Spain and later in Europe—were sometimes regarded with suspicion, particularly if they mimicked living beings too closely.8 Alchemy and astrology, both reliant on complex tools and techniques, walked a fine line between sanctioned science and condemned sorcery, depending on ecclesiastical interpretation.

The Church also acted as a regulator of time through its promotion of mechanical clocks in monasteries. This technology, emerging around the thirteenth century, was developed in part to regularize the hours of prayer.9 As such, ecclesiastical sponsorship facilitated both the development and dissemination of this highly influential technology—while simultaneously controlling its social meaning and use.

Urban Ordinances and Civic Regulation

As European cities expanded in the later Middle Ages, municipal governments began to assume more active roles in regulating technological activity. City councils passed ordinances regulating the placement and operation of forges, tanneries, and other industrial sites, particularly when these posed fire or sanitation risks. In thirteenth-century Paris, for example, tanneries were restricted from operating near water sources used for drinking.10 Similarly, in London, laws were passed to limit noise pollution from metalworking shops during nighttime hours.11

Municipal authorities also standardized infrastructure-dependent technologies. Aqueducts, sewer systems, and bridges were communal resources, and cities invested in both their construction and upkeep. Regulations governed the use of public wells and the disposal of waste, showing that even non-mechanical technologies like sanitation systems were tightly controlled.12 In these ways, urban technology was shaped not only by engineering capacity but by public health, urban planning, and social order.

Technological Secrecy and the Politics of Innovation

Technological secrecy was itself a regulatory mechanism. In the absence of modern intellectual property laws, knowledge was often protected by custom, oath, or physical containment. The aforementioned Venetian glassmakers are a prominent example, but similar patterns existed across Europe. Certain metallurgical techniques—especially those involving bronze casting and coin minting—were tightly controlled by royal or episcopal authorities.13 In some cases, royal privileges granted inventors or workshops exclusive rights to a process for a limited time, functioning as an early form of patent. These privileges were not always permanent but served to both encourage innovation and limit its diffusion.14

The control of knowledge extended to books and manuscripts as well. Scriptoria in monasteries limited who could access technical manuals, and scribes were sometimes forbidden from copying certain texts without approval.15 Thus, the regulation of technology in the Middle Ages extended beyond tools and processes into the realm of literacy and intellectual access.

Conclusion

The regulation of technology in the medieval world was multifaceted, operating across religious, economic, legal, and social spheres. It was not centralized in the modern sense, but it was systematic, persistent, and often deeply embedded in local power structures. Guilds protected the integrity of crafts and guarded trade secrets. Lords enforced monopolies on essential processing technologies. The Church imposed moral limits and promoted timekeeping. Urban governments regulated industry for public safety. Across all these domains, technology was never free of oversight. Innovation in the Middle Ages proceeded within a dense web of constraint—some protective, some suppressive, but all deeply intertwined with the fabric of medieval life.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Epstein, Steven A. Wage Labor and Guilds in Medieval Europe (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991), 35–39.

- Carlo M. Cipolla, Before the Industrial Revolution: European Society and Economy, 1000–1700, 3rd ed. (New York: Norton, 1993), 169.

- Richard Holt, The Mills of Medieval England (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1988), 72–75.

- Marc Bloch, Feudal Society, vol. 1, The Growth of Ties of Dependence (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1961), 232–36.

- Lynn White Jr., Medieval Technology and Social Change (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1962), 44–46.

- Jean Gimpel, The Medieval Machine: The Industrial Revolution of the Middle Ages (New York: Penguin, 1976), 19–22.

- Katharine Park, Secrets of Women: Gender, Generation, and the Origins of Human Dissection (New York: Zone Books, 2006), 61–65.

- E.R. Truitt, Medieval Robots: Mechanism, Magic, Nature, and Art (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015), 102–107.

- Gimpel, The Medieval Machine, 104–106.

- Georges Duby, The Three Orders: Feudal Society Imagined (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980), 181.

- Sylvia L. Thrupp, The Merchant Class of Medieval London, 1300–1500 (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1989), 117.

- Martha C. Howell and Walter Prevenier, From Reliable Sources: An Introduction to Historical Methods (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2001), 84.

- Pamela O. Long, Openness, Secrecy, Authorship: Technical Arts and the Culture of Knowledge from Antiquity to the Renaissance (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001), 92.

- Joel Mokyr, The Lever of Riches: Technological Creativity and Economic Progress (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 47.

- Elizabeth Eisenstein, The Printing Revolution in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 14.

Bibliography

- Bloch, Marc. Feudal Society. Vol. 1, The Growth of Ties of Dependence. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1961.

- Cipolla, Carlo M. Before the Industrial Revolution: European Society and Economy, 1000–1700. 3rd ed. New York: Norton, 1993.

- Duby, Georges. The Three Orders: Feudal Society Imagined. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980.

- Eisenstein, Elizabeth. The Printing Revolution in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

- Epstein, Steven A. Wage Labor and Guilds in Medieval Europe. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991.

- Gimpel, Jean. The Medieval Machine: The Industrial Revolution of the Middle Ages. New York: Penguin, 1976.

- Holt, Richard. The Mills of Medieval England. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1988.

- Howell, Martha C., and Walter Prevenier. From Reliable Sources: An Introduction to Historical Methods. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2001.

- Long, Pamela O. Openness, Secrecy, Authorship: Technical Arts and the Culture of Knowledge from Antiquity to the Renaissance. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001.

- Mokyr, Joel. The Lever of Riches: Technological Creativity and Economic Progress. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

- Park, Katharine. Secrets of Women: Gender, Generation, and the Origins of Human Dissection. New York: Zone Books, 2006.

- Thrupp, Sylvia L. The Merchant Class of Medieval London, 1300–1500. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1989.

- Truitt, E.R. Medieval Robots: Mechanism, Magic, Nature, and Art. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015.

- White, Lynn Jr. Medieval Technology and Social Change. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1962.

Originally published by Brewminate, 06.30.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.