By the end of the 19th century, Americans had begun to see water as a matter of public policy.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Water as Necessity and Crisis

From the colonial era through the 19th century, American communities faced persistent struggles to secure safe, reliable water supplies. These challenges were shaped by geography, climate, technological limitations, and rapid urban growth. Water was essential not only for individual survival, but for agriculture, sanitation, fire control, and industrial development. Yet for much of early American history, systems for sourcing and distributing clean water remained fragile, improvised, and dangerously inadequate.

Colonial Realities: Drawing from the Land

In the 17th and 18th centuries, most colonial settlements depended on natural water sources such as rivers, streams, springs, and shallow wells. These sources were often shared by entire communities and vulnerable to seasonal variability. Colonists frequently settled near waterways for convenience, but proximity to water did not guarantee its cleanliness. Runoff from animal pens, human waste, and refuse often fouled wells and streams, especially in densely packed urban settlements like Boston and Williamsburg.1

In rural areas, families dug their own wells, but the lack of standardized construction often led to shallow, unprotected sources easily contaminated by surface runoff. Moreover, early settlers had little understanding of waterborne disease. Epidemics of dysentery, typhoid, and cholera were commonly traced to impure water, though causation was often misunderstood.2

Access to water could also provoke conflict. In contested frontier regions, disputes between colonists and Native American communities often included competition for reliable water sources, exacerbating tensions and contributing to broader struggles over land and resources.3

Engineering Solutions: Early Urban Infrastructure

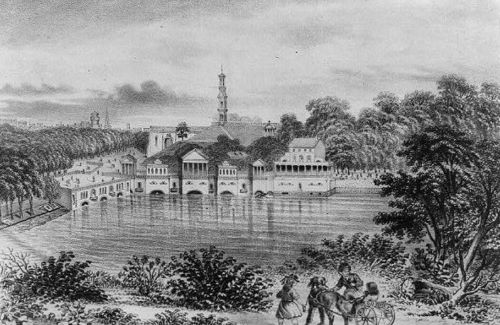

As cities grew in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the inadequacy of natural sources became acute. The response was a new era of municipal waterworks. The most ambitious early project was Philadelphia’s Fairmount Water Works, begun in 1799 and operational by 1815. Initially powered by steam engines, the system pumped water from the Schuylkill River into elevated reservoirs, allowing gravity-fed delivery to homes and hydrants.4

New York followed with the Manhattan Company in 1799, a private venture that laid wooden water mains throughout lower Manhattan. Yet contamination remained rampant, and the company’s dual function as a bank (it eventually became Chase Bank) compromised its investment in public health.5 Boston, Baltimore, and other growing cities launched similar projects, often using hollowed logs as pipes before the widespread adoption of iron mains.

These projects represented a shift toward public health infrastructure, but they also reflected rising social stratification. Wealthier neighborhoods received better service and cleaner water, while poorer districts continued to rely on polluted wells and street pumps.6

Industrialization and Urban Growth

The 19th century brought rapid industrial growth, urbanization, and the emergence of public health reform movements. Cities such as Chicago, Cincinnati, and St. Louis ballooned in size, but water systems struggled to keep pace. Rivers once used for drinking became open sewers.

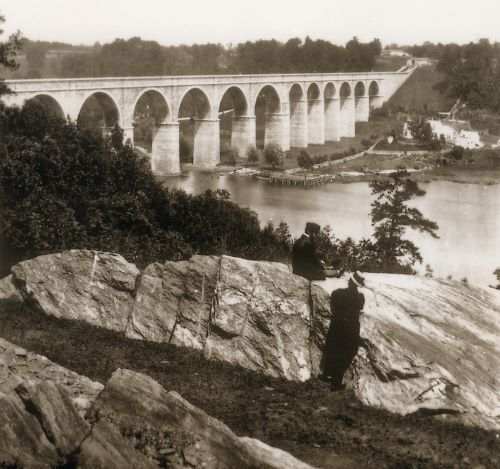

The most iconic response to these challenges was New York City’s Croton Aqueduct, completed in 1842. It brought water from 40 miles north via a masonry conduit into a city of over 300,000. The aqueduct enabled cleaner public water, extensive fire hydrants, and eventually modern indoor plumbing.7 But even Croton faced strain by the 1860s, requiring expansions and eventual replacement with the New Croton Aqueduct in the 1890s.

Chicago offers another case study. Drawing drinking water from Lake Michigan, the city found itself recycling its own sewage by the mid-19th century. In response, engineers undertook a massive earth-moving feat: reversing the flow of the Chicago River away from the lake in 1900.8 This required years of canal-building and remains one of the largest engineering projects in American municipal history.

Water in the Countryside: The Drought Problem

Outside urban centers, Americans continued to rely on wells, springs, and rain catchment through much of the 19th century. Western expansion introduced new obstacles. Arid climates across the Great Plains and Southwest made water access precarious. Settlers in these areas often dug cisterns, built windmills to pump groundwater, or transported water by wagon from distant sources.

In California, the Gold Rush strained both surface and groundwater sources. Hydraulic mining polluted rivers, and demand from booming cities like San Francisco led to the creation of large-scale aqueducts and reservoirs later in the century. These water wars would culminate in battles like the Owens Valley conflict in the early 20th century, but their roots lay in the 19th century.9

Conclusion: Water as Public Good and Political Challenge

By the end of the 19th century, Americans had begun to see water not merely as a private resource or natural gift, but as a matter of public policy. Cities developed sanitation departments and passed laws to regulate wells, reservoirs, and piping. Yet water access remained uneven, shaped by class, race, and geography. While water systems advanced dramatically from colonial improvisation to industrial infrastructure, their effectiveness and fairness remained ongoing struggles—ones that continue to echo in the twenty-first century.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Jack Larkin, The Reshaping of Everyday Life, 1790–1840 (New York: Harper & Row, 1988), 71.

- Charles E. Rosenberg, The Cholera Years: The United States in 1832, 1849, and 1866 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962), 21–23.

- Colin G. Calloway, The Scratch of a Pen: 1763 and the Transformation of North America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), 84–86.

- Martin V. Melosi, The Sanitary City: Urban Infrastructure in America from Colonial Times to the Present (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000), 42–45.

- Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 368–72.

- Melosi, The Sanitary City, 49.

- David Soll, Empire of Water: An Environmental and Political History of the New York City Water Supply (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2013), 24–28.

- Harold L. Platt, The Electric City: Energy and the Growth of the Chicago Area, 1880–1930 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991), 68–70.

- Norris Hundley Jr., The Great Thirst: Californians and Water—A History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), 112–115.

Bibliography

- Burrows, Edwin G., and Mike Wallace. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Calloway, Colin G. The Scratch of a Pen: 1763 and the Transformation of North America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Hundley, Norris Jr. The Great Thirst: Californians and Water—A History. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001.

- Larkin, Jack. The Reshaping of Everyday Life, 1790–1840. New York: Harper & Row, 1988.

- Melosi, Martin V. The Sanitary City: Urban Infrastructure in America from Colonial Times to the Present. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000.

- Platt, Harold L. The Electric City: Energy and the Growth of the Chicago Area, 1880–1930. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991.

- Rosenberg, Charles E. The Cholera Years: The United States in 1832, 1849, and 1866. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962.

- Soll, David. Empire of Water: An Environmental and Political History of the New York City Water Supply. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2013.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.04.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.