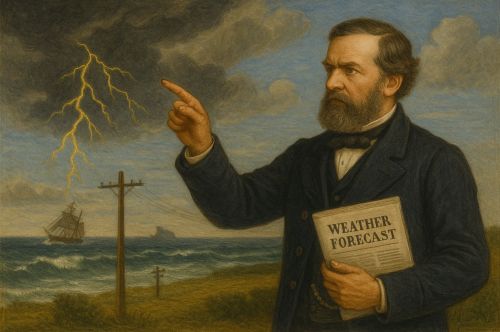

Robert FitzRoy was not only the first popular weather forecaster; he was an architect of the very idea that weather knowledge could be a public good.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: A New Science for a New Public

When Robert FitzRoy began publishing daily weather forecasts for the British public in the 1860s, he was not merely communicating scientific data. He was reframing the relationship between ordinary citizens and the natural world. For centuries, weather prediction in Britain had belonged to the realm of sailors’ lore, farmers’ proverbs, and astrological tables. FitzRoy, armed with barometers, wind charts, and a network of telegraph stations, offered something radically different: a science that claimed to predict tomorrow’s weather based on measurable patterns, not inherited superstition.1

This was more than a technical achievement. It was a cultural intervention, carried out in the very decades when Victorian Britain was learning to think of the sea, the skies, and the seasons as subjects for organized knowledge. FitzRoy’s work, celebrated by some and mocked by others, was as much an exercise in public persuasion as in meteorology. The “forecast,” a word he popularized, entered the public vocabulary as a promise that knowledge might temper nature’s dangers.

FitzRoy Before the Forecast: From the Beagle to the Board of Trade

Robert FitzRoy’s path to meteorology was anything but direct. Born in 1805 into an aristocratic family, he first came to prominence as captain of HMS Beagle during Charles Darwin’s famous voyage. His naval career immersed him in the discipline of reading the sea and the sky, where barometric changes could mean the difference between safety and shipwreck.2 This experience sharpened his conviction that weather signs could be systematized.

By the time he became head of the Meteorological Department of the Board of Trade in 1854, FitzRoy had already established himself as a meticulous observer and a cautious innovator. His charge was to improve safety at sea, especially for fishing communities along the British coast. To that end, he initiated a network of stations to collect simultaneous weather observations, transmitted via the electric telegraph. The novelty lay in the speed: data could now be gathered across hundreds of miles and analyzed in a matter of hours.3 This infrastructure laid the foundation for public weather forecasting as a real-time enterprise rather than a retrospective compilation.

The First Forecasts: Science Meets Public Curiosity

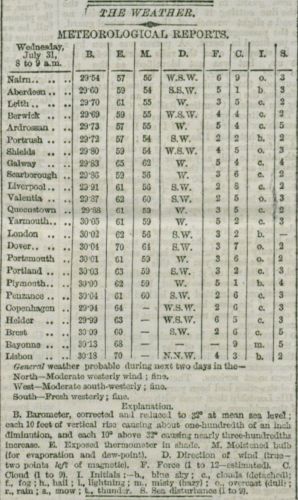

In August 1861, FitzRoy published the first daily weather forecast in The Times. It was brief, written in plain language, and aimed at a readership unaccustomed to seeing the future weather in print. The move was bold. Meteorology was still a fledgling science, and its predictive claims were vulnerable to both ridicule and disappointment. FitzRoy’s forecasts were based on patterns of barometric pressure, wind direction, and cloud formation, interpreted with an experienced sailor’s intuition.4

The public response was mixed. Some found the forecasts invaluable, especially those in maritime professions, while others mocked their occasional inaccuracies. Newspapers delighted in pointing out failed predictions. Yet FitzRoy persevered, refining his methods and expanding the scope of the forecasts. In time, the idea that the government could and should provide such information began to take root in the public mind.

It is here that FitzRoy’s role as a popularizer becomes evident. He was not merely disseminating data; he was building trust in a new kind of authority, one rooted in instruments, charts, and networks, rather than in personal weather lore. Each forecast was a small act of persuasion, inviting the reader to believe that tomorrow’s conditions could be anticipated through reasoned analysis.

Instruments, Warnings, and the Maritime Public

FitzRoy’s public meteorology was inseparable from his efforts to protect life at sea. He distributed barometers to fishing ports, often accompanied by instructions on how to interpret sudden drops in pressure as warnings of storms.5 These “FitzRoy barometers” became fixtures in coastal communities, their brass faces as much a part of the maritime landscape as lifeboats and lighthouses.

His storm warning system, inaugurated in 1861, used visual signals, cones and drums hoisted at port, to alert mariners of approaching gales. The combination of localized warnings and printed forecasts marked a decisive shift toward a proactive relationship with the weather. No longer was the sailor left to his own devices; the state had taken a hand in the management of atmospheric risk.

Here again, the social dimension is as important as the technical. FitzRoy’s warnings represented a form of paternal care from the Victorian state, an intervention in the dangerous, often fatal uncertainties of working life. That care, however, rested on the public’s willingness to believe in the science behind the signals.

Controversy, Strain, and Tragic End

Despite his achievements, FitzRoy’s position was fraught with pressures. Forecasting was inherently uncertain, and the science of the 1860s could not guarantee perfect accuracy. Critics accused him of overreaching and wasting public funds. Newspapers lampooned his missed predictions, undermining public confidence. FitzRoy, deeply sensitive to criticism, felt these attacks acutely.

His work was also hampered by the limits of contemporary meteorological theory. Without satellite imagery or global data networks, his forecasts relied on fragmentary information, and weather systems could develop beyond the reach of his observational grid. The strain of constant public scrutiny, coupled with personal and financial difficulties, contributed to his suicide in 1865.6

In the aftermath, the Meteorological Office continued his work, but the forecasts were temporarily discontinued. Only later would FitzRoy’s pioneering role be fully recognized, and his name reclaimed as that of a founder rather than a failed experimenter.

Legacy: Forecasting as a Public Right

Today, weather forecasts are so embedded in daily life that it is easy to forget how radical FitzRoy’s project was. He took meteorology from the specialist’s desk to the breakfast table, from the ship’s log to the printed page. His insistence that the state bear responsibility for public warning systems set a precedent for modern disaster preparedness.

FitzRoy’s forecasts were imperfect, but their cultural impact was profound. They invited ordinary people to imagine themselves as participants in a national conversation about the weather, one grounded not in folklore but in an emerging science. In this sense, Robert FitzRoy was not only the first popular weather forecaster; he was an architect of the very idea that weather knowledge could be a public good.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Katharine Anderson, Predicting the Weather: Victorians and the Science of Meteorology (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005), 113–118.

- Charles Darwin, The Voyage of the Beagle (London: John Murray, 1839), 5–8.

- John Gribbin, The Scientists: A History of Science Told Through the Lives of Its Greatest Inventors (New York: Random House, 2004), 336–339.

- Anderson, Predicting the Weather, 132–134.

- Peter Moore, The Weather Experiment: The Pioneers Who Sought to See the Future (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015), 211–215.

- Moore, The Weather Experiment, 295–298.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Katharine. Predicting the Weather: Victorians and the Science of Meteorology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

- Darwin, Charles. The Voyage of the Beagle. London: John Murray, 1839.

- Gribbin, John. The Scientists: A History of Science Told Through the Lives of Its Greatest Inventors. New York: Random House, 2004.

- Moore, Peter. The Weather Experiment: The Pioneers Who Sought to See the Future. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.11.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.