To whom did the princes’ and nobles’ ‘own entrusted lands’ truly belong?

By Dr. Duncan Hardy

Assistant Professor of History

University of Central Florida

Abstract

This article provides an overview of the historiography on the political composition of the late medieval Holy Roman Empire, especially regarding “territoriality” and the rival theories and criticisms that have since emerged. It also illustrates the complexities of political ideas and practices at multiple levels within the Empire, drawing on a selection of evidence from throughout the German lands, from the bishoprics and principalities of the North and Baltic Sea littorals to the kaleidoscopic lordships and communes of upper Germany. Building on the latest research into the intersection of local, regional, and imperial ideologies and structures of power, it concludes with some brief proposals about how a more nuanced understanding of “territorial” power can be understood within the Empire’s wider political culture.

Introduction

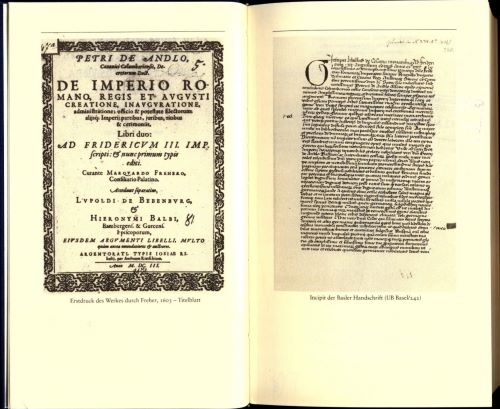

In 1460 Peter von Andlau, the illegitimate child of an Alsatian knight and a professor of law at the newly founded University of Basel, attempted to summarise the hierarchy of power and jurisdiction in the Holy Roman Empire. The resulting Libellus de Cesarea monarchia (‘little book on the imperial monarchy’) presented a history and juridical theory of imperial monarchy from Antiquity to his own time, highlighting the translation of the imperial dignity to the German people and the ideal form and functioning of the Romano-German body politic under the emperors’ oversight. Andlau drew on a rich array of authorities, from Gregory the Great to Poggio Bracciolini, harmonised to the best of his ability within a canonist and Thomist framework. These sources emphasised a Justinianic view of the imperial monarchy as enjoying a plenitude of power, delegated conditionally to princes and nobles. However, Andlau had to acknowledge in places the gulf between this monistic, top-down ideal and the realities of political structures and political life in the fifteenth-century German lands of the Empire. In his explanation of how the feudal order of nobles (Heerschildordnung) was supposed to assist the emperor in protecting and administering his realm, he recognised that they had landed possessions of their own to manage:

All the aforesaid princes and nobles were installed to assist and serve the Holy Empire, through which earthly monarchy may most perfectly be constituted. To them falls the obligation to govern political affairs in their own entrusted lands.1

To whom did the princes’ and nobles’ ‘own entrusted lands’ truly belong? In the sense that the emperor was the ultimate source of jurisdiction in the Holy Roman Empire, and presided over all ranks of aristocrats and cities within it, the Libellus seeks to give the impression that they stemmed from the monarchy. To the extent that this was true, the Empire resembled most other European kingdoms in which lands and powers were held by parties other than the monarch, but under his ultimate notional authority. Yet Andlau’s wry comments elsewhere about the failure of the nobility to live up to its assigned role within the Empire, and the corresponding weakness of the Roman kings and emperors, hint at an exceptionally sharp division between lands within the Empire (and specifically in Germany – Germania or Alamania) ruled by princes, nobles, and cities, and lands directly ap-pertaining to the monarchs.2 Traditionally, the power bases of these princes, nobles, and cities – what Peter von Andlau called their terrae – have been described by historians as ‘territories’.

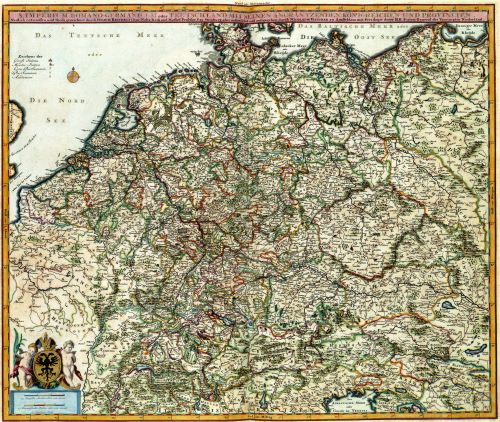

The aim of this article is to explore whether the concept of ‘territories’ is useful for making sense of the authorities below the monarchy that existed in the late medieval and early modern Holy Roman Empire. Before considering the applicability of the term to political elites’ terrae, it is important to establish how widespread Andlau’s division between these last and the monarchical layer of authority was. It is certainly evident in more prosaic narratives and legal documents. Already the mid-fourteenth century chronicle of Heinrich Taube von Selbach, a cleric in Eichstätt, drew an acute distinction between the lands of Emperor Ludwig IV (r. 1314-1347), of the Wittelsbach house of Bavaria, and the wider components of the Empire. ‘In the whole time of his reign’, claimed the chronicler, ‘his own land [terra sua propria] met his financial needs; the cities and lands of the Empire [civitates et terre imperii] provided very few funds’.3 As vernacular sources rendered this multivalent term terra(e) in German as Land(e), and developed a related web of labels for their owners and rulers, this cleavage deepened. From the second half of the fifteenth century, and throughout the sixteenth, documents produced by monarchs, princes, and cities customarily contrasted the ‘German land(s)’ (teutsche lande, Teutschsland), the imperial ‘estates’ or ‘members’ (stende, glider), or the ‘German nation’ (teutsche nation) on the one hand, and the emperors’ own power bases on the other.4 These were known by the time of Maximilian I (r. 1486-1519) as the ‘hereditary lands’ (erblande) – that is, the Habsburg patrimony located mainly in Austria and the Burgundian Low Countries.5 The power and pervasiveness of this conceptual divide has inspired historians of the late medieval and early modern Empire to speak of an ‘institutionalised dualism’ within its constitutional system.6

By the Late Middle Ages, then, and into the early modern period, there was a clear and constitutionally signif icant distinction in Germany between ‘lands’ belonging to the Romano-German monarch and those controlled by other elites in the Holy Roman Empire (German princes and prelates, nobles, and cities and communes). As noted above, the tendency in modern German historiography has been to describe the latter as ‘territories’ (Territorien), and the process by which a large proportion of the German lands became increasingly autonomous of the monarchy under their local rulers has been dubbed ‘territorialisation’ (Territorialisierung).7 Although adherents of this view have not always defined what they mean by ‘territory’, often implicit within it is eighteenth-century German jurists’ understanding of what they called a territorium clausum: an unambiguously spatially bounded zone, integrated under the undisputed jurisdiction of a single discrete administration.8 In recent decades, some historians within and beyond German-speaking scholarly circles have begun to criticise and unpick this well-worn narrative and theoretical framework. Mostly absent from this long-running discussion, among either proponents or opponents of territorialisation, is a consideration of whether any meanings of ‘territory’ could be applied to late medieval and early modern Germany that do not necessitate the existence of spatially delineated units. Here Stuart Elden offers a new perspective of potential relevance to the German debate, with his call to stop taking for granted that territory must be equated with a homogeneously governed ‘bounded space’, and instead to treat it as a contextually contingent ‘political strategy’.9 We will have occasion to consider the applicability of this more nuanced approach as we examine local and regional imaginings and configurations of power in the Holy Roman Empire.

In the sections that follow, this article will consider whether the possessions and approaches to lordship and government of the imperial elite should indeed be considered ‘territories’ in any sense, in light of the surviving evidence and its implications for the vocabulary we might employ to apprehend the Empire’s political configuration in the fourteenth to sixteenth centuries. As this question is, at its heart, historiographical in nature, the first half of the article consists of a survey of the narratives and interpretations that have constructed the idea of late medieval and early modern German Territorien. We shall see how these have changed over time, and the criticisms that they have received from some quarters. Taking up some of the points made by recent scholarship, the article will then briefly explore the ways in which local and regional forms of authority and community did – or did not – correspond with possible notions of territory between about 1300 and 1600. It will examine this at the discursive level, through the terminology and connotations of ‘territory’-esque words found in primary sources. The more concrete underpinnings of lordship and government in all their forms will then be considered, including the financial resources and transactional systems available to political actors, the tenurial formats (pledges, fiefs, etc.)

through which they apportioned and held land-based authority, and the personnel involved in wielding power on a regional and local level. Finally, the article will highlight the interdependence among notionally autonomous actors that exercising authority over almost any defined ‘territorial’ space in the German lands entailed. Needless to say, an article of this length does not aspire to exhaustivity either in its treatment of the historiography or of the potentially relevant historical evidence. Rather, the point is to highlight where the debate about ‘territories’ in the German lands – or alternative models to them – stands in 2021, and to indicate through an unsystematic tour d’horizon of relevant themes and types of evidence how less plausible assumptions and narratives might be modified by alternative perspectives. Only then will it be possible to determine the applicability of ‘territorial’ vocabulary for this area of Europe in this period.

Narratives of German Territorialization and Their Discontents

Teleologies of Territorial Statehood to the Mid-Twentieth Century

On the eve of the Holy Roman Empire’s dissolution in 1806, political power within it was largely exercised by princes who claimed ‘territorial supremacy’ or quasi-‘sovereignty’ (superioritas territorialis, Landeshoheit), concepts popularised from the later seventeenth century onwards. The state-like character of these territorial entities was complicated only by their existence within the broader framework of the Empire – a situation that had already irritated the influential jurist Samuel von Pufendorf in the 1660s.10 Since the early nineteenth century, this post-Westphalian end point of German Kleinstaaterei has shaped the way in which historians write about the earlier political configurations in the Empire.

As we have already seen, the practical absence of central, monarchical authority over the Holy Roman Empire has been inextricably bound up with the notion that other actors held power over fragmented terrae or Lande within Germany. In the nineteenth and early twentieth century, this observation generally elicited despair and negativity in nationalist German scholars. It lay at the heart of the notion that Germany had followed a ‘special path’ (Sonderweg).11 The Empire, so the story went, had missed the opportunity to form the kernel of a German nation state. The splendour and might of the earlier medieval emperors presaged the centralisation of a Reich with a predominantly German character, but this project foundered on quixotic dreams of universal authority and the parochial greed of the princes. It had never been the case, of course, that any medieval emperors ruled directly and uniformly over a bounded imperial space. But through a combination of the alienation of prerogatives and assets attached to the monarchy, its reconfiguration as an elected office influenced by the seven prince-electors, and the rise of a wider princely elite, a devolution and layering of authority within the Empire became starkly apparent. The acquisition of power and resources by princes, nobles, and towns in the German localities – or at least the greater clarity with which we can observe their position as the source material becomes more abundant over time – is called ‘territorialisation’ in the historiography of the Holy Roman Empire.12 An important subset of scholars, beginning in the late nineteenth century and continuing into the late twentieth, even ventured to identify the subsidiary powers within the Empire as ‘territorial states’ (Territorialstaaten).13

A parallel scholarly tradition also adopted a territorial vocabulary to discuss social, political, and cultural dynamics in Germany – but, in contrast to the nationalist interpretation, tended to see ‘territorialisation’ as a positive development. This was regional history (Landesgeschichte, and its interdisciplinary counterpart Landeskunde). The very same Kleinstaaterei and cultural particularism bemoaned by nationalists stimulated the creation of a plethora of regional history societies and journals, often under the patronage of princes and kings (before 1871) and, subsequently, federal states.14 In this framework, the emergence of politically coherent territories was a process to be celebrated. LandeshistorikerInnen strained to identify markers of territorialisation that seemed to point to the subsequent rise of the princely territorial states or Bundesländer that existed in their own time, such as jurisdictional consolidation, the rise of fiscality, the creation of districts and off ice-holding administrators, and so on. Regional historians have therefore been even less hesitant to ascribe to medieval and early modern entities the characteristics of nascent statehood with territorial dimensions. As late as 1986, Alois Gerlich could discern in what he identified as medieval territories a ‘primitive statehood predicated on a defined area of land’ (‘flächenbezogener Primitivstaatlichkeit’).15

While most strands of German historiography have been united in placing territorialisation at the heart of their interpretations, there has been less agreement over when this process began in earnest. Some of the dominant historians of the nineteenth century – Leopold von Ranke and Heinrich von Treitschke, for instance – saw the pre-modern Territorium as lacking the trappings of true statehood, which it supposedly acquired in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, alongside the Reformation and other ostensible signs of incipient modernity.16 Others were less hesitant to read medieval sources teleologically, with the post-Westphalian sovereign states in mind. In a historical compendium of constitutional law published in 1872, Hermann Schulze situated Prussia’s origins in medieval Brandenburg, which he already termed a Territorialstaat, albeit one with an ‘unfinished form’. For Schulze, the putative jurisdictional supremacy of the medieval margraves already formed the ‘essential core of sovereignty [“Landeshoheit”]’.17

The view that territorial statehood developed in the Middle Ages gained in prominence into the middle of the twentieth century. In Theodor Mayer’s much-cited thesis, an early medieval Personenverbandsstaat (a state defined in relation to its ruling elite) gave way to a more territorialised form of statehood (defined by spatial boundaries under given authorities) in the eleventh and twelfth centuries.18 His interpretation elicited many criticisms. Most notably, Otto Brunner supported the regional basis for authority in the German-speaking lands, but rejected the abstract language of statehood as anachronistic, preferring to define the Land as the product of an aristocratic legal culture predicated on the right to feud in defence of one’s honour and patrimony and the rise of late medieval ‘territorial’ elite communities or estates (Landschaften, Landstände).19 Brunner’s landmark legal-cultural and communitarian insights have influenced virtually all subsequent historiography of politics in the late medieval German lands, but his radical rejection of étatiste concepts, and post-medieval vocabulary more generally, failed to gain much traction. The idea of the Territorialstaat persisted in the German scholarly conversation, despite disagreements about its applicability to specific time periods.

Shifting Post-War Interpretations of Territorialization

After 1945, the negative nationalist view of the division of the Reich into territories as a failure of central government mostly fell out of favour. However, the narrative of ‘territorialisation’ in Germany endured, and in some respects gained strength. There are several reasons for this. German historiographical debates tend to centre on long-standing abstract and ideal-typical concepts (Begriffe). Historians have expended great intellectual energy on preserving terms like Territorialisierung, albeit in modified form as new research challenges old assumptions. This is especially the case in legal and constitutional history (Rechts-/Verfassungsgeschichte). The focus on putative territories was also stimulated by a resurgence in interest in tracing and comparing pathways of state formation across pre-modern Europe.20 In this context, it has become a cliché of late medieval and early modern German scholarship that although the Holy Roman Empire itself did not ‘achieve’ centralised statehood on the Western European model, this process did occur at the devolved level of the princely territories or territorial states.21 Finally, Landesgeschichte – institutionalised in West German universities – flourished in the post-war decades. Sometimes it took on a more critical and self-reflective guise, applying new methodologies to local topics. Nevertheless, the ‘territorial’ paradigm has persisted in regional history, since it naturally lends itself to research at this scale. The words ‘territory’ (Territorium) and the more explicitly statist Flächen-/Territorialstaat therefore remain central (if sometimes ill-defined) components of the scholarly vocabulary of historians of the Holy Roman Empire in the fourteenth to the sixteenth centuries and beyond.22

Alongside this longevity, there have also been important changes in the scholarly orthodoxy about how the specificities of the territorial configuration of the German lands should be interpreted. In the 1970s-2000s a new wave of medieval and early modern scholarship, spearheaded by Peter Moraw and Volker Press, criticised the blinkered emphasis on the territorial level of politics alone, arguing that historians had ignored the importance of the Reich within which these territories were located, and artificially separated regional and imperial history.23 While maintaining an interest in the growth of territorial structures, Moraw in particular sought to integrate the history of the German localities within what he saw as the Empire’s evolving ‘constitution’ or ‘political system’. More recently, Barbara Stollberg-Rilinger has emphasised the importance of the early modern Reich as a symbolic fount of legitimacy for its constituent authorities.24

In light of this wider focus and new advances in regional case studies, late medievalists have begun in the last couple of decades to shy away from the idea that the Empire contained territorial states. (This is much less true of early modern historiography, not least because of the ‘confessionalisation’ schema in Reformation studies, which posits the emerging territorial state as a key actor in shaping and entrenching confessional identities in Central Europe.) Instead of territorial statehood, historians of regional powers have embraced the less anachronistic concept of Landesherrschaft (‘territorial/landed lordship’). In the earlier twentieth century this described the development of late medieval territories out of the power bases of the post-Carolingian nobility. Historians have broadened its meaning in recent decades, and redefined Landesherrschaft according to the specific entity under study, whether the fourteenth-century March of Brandenburg or the sixteenth-century archbishopric of Trier.25 In this respect its flexible usage anticipates a key criticism of the ‘territorial’ model, namely that it implies that all German political units had similar characteristics, whereas recent scholarship has emphasised the diversity of forms and pathways taken by the various ‘territories’. This extreme variation arguably throws into question the value of ‘territorial lordship’ as a catch-all label, but certain common characteristics are typically assumed within it. An oft-repeated definition of Landesherrschaft holds that it consisted of the ‘bundling’ (Bündelung) of rights and powers related to property, jurisdiction, and authority over hierarchies of subordinates and subjects in the hands of a specific lord (usually a prince). Crucially, these bundled rights and powers were exercised within a spatially defined and increasingly discrete and cohesive area (hence this form of lordship fits neatly within the narrative of German territorialisation over time).26

Critiques of Territorial Models

In recent years even the Landesherrschaft paradigm has been called into question from multiple perspectives. By far the most important critic is the late Ernst Schubert, whose seminal book Fürstliche Herrschaft und Territorium im späten Mittelalter (first published in 1996) remains the definitive overview of the themes and problems related to putative territorial authority in this period. Schubert’s critique dismantles some of the comfortable assumptions about the German territories from several angles. In the primary sources the word Land, which underpins so many ‘territorial’ concepts employed in the scholarship, rarely denoted a coherent political space that a German prince claimed to rule.27 Historians who hope to sidestep the anachronism of the word ‘territorial state’ must reckon with the unwieldiness of Landesherrschaft, which remains so broad and ill-defined as to be almost meaningless as an analytical category.28 Crucially, Schubert argues that fundamental elements of politics in the fourteenth to sixteenth centuries were not ‘territorial’/spatial in character. The unrelenting focus on territorialisation misses the significance of dynastic (i.e. interpersonal and biological) factors, for instance, while the undeniable bureaucratisation of princely government was more about the growth of courts and chanceries and their select personnel than the uncontested administration of spatially defined territorial zones.

Other more recent criticisms of territorial paradigms have also been proposed. Christine Reinle has highlighted the deterministic beliefs that underpin territorialisation, such as the notion that pre-modern actors always sought to maximise their power and property (Machtmaximierung), which ignores the many other complex and culturally specific values that motivated them.29 In an important study of the construction of borders within the pre-modern Reich, Andreas Rutz has shown that spatial conceptions of topographies, societies, and cultures certainly existed in Germany, including in the form of local administrative units. However, these were highly contingent, friable, and rarely amounted to cohesive delineations of princely territorial units as implied in conventional narratives of territorialisation.30

Where, then, does this leave the concept of ‘territory’ in the context of the late medieval and early modern German lands? Clearly, it has been taken for granted for too long, and the use of ‘territorial’ vocabulary and the assumptions that lie behind it is rightly being challenged. At the same time, some power wielders in the Empire undeniably were consolidating their authority in this period, and sometimes that consolidation had spatial dimensions. The second half of this article will therefore examine some of the specificities of politics in the Empire, and consider whether the term ‘territory’ is ever justified, even in the open-ended and context-sensitive Eldenian sense.

The Many Meanings of ‘Land’ and Contemporary Conceptualizations of Power Wielders

Many narratives of German territorialisation rely on the presence of a land-related discourse in the primary sources. This is true of the notion that terrae/Lande denoted princely territorial states-in-the-making, for example, and – from a rather different perspective – Otto Brunner’s argument that the pre-modern Empire was made up Lande defined by a mix of princely lordship and customary noble communities. But did the term Land and its cognates necessarily denote a discrete, politically delineated unit ruled by a prince? Recent research has dismantled this central plank of the territorialisation thesis.

Perhaps the main resonance of the word Land in late medieval sources was in reference to the local customs (also called ‘lantsit’) of groups of people, with only a fuzzy connection to a defined space. German rulers employed the universal phrase ‘[our] land(s) and people(s)’ (Land und Leute) in charters and treaties to refer not to a territorial zone but a cluster of communities of custom under their authority.31 A related but larger-scale use for Land was to refer to cultural-linguistic zones such as Alsace, Westphalia, Swabia, or Franconia, which were fragmented among many autonomous rulers between 1300 and 1600, and can in no way be considered territories in any political sense of the word. Some of these had once been loosely encompassed within now-defunct – or, in the case of Saxony, much-reduced and displaced – duchies.32

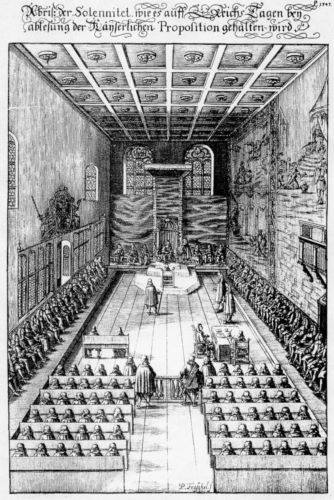

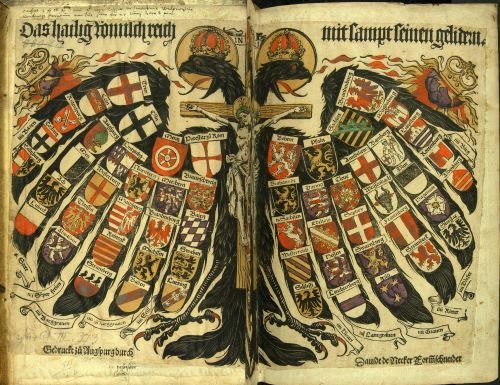

The rulers and entities that constituted the members and estates of the Holy Roman Empire, within and beyond these cultural-linguistic Lande, were almost never designated using a territorial or spatial vocabulary in this period. In ordinances issued at imperial diets by the monarchs and estates, the power wielders in the Empire were not addressed as rulers of ‘lands’ or ‘territories’, but as title-holding individuals or bodies under a collective imperial umbrella (electors, spiritual and secular princes, counts, barons, knights, cities, and communes, and their vassals, officers, and subordinates).33 A similar level of abstraction is evident in symbolic and idealised representations of the Empire’s head and members known as Quaternionen, that emerged in the fifteenth century and became ubiquitous in the sixteenth. Here the imperial body politic appears as an amalgam of its emperor, seven electors, and sets of four representatives of various types of imperially immediate status holders, from dukes to villages, each status holder embodied by its heraldic arms.34

The ‘territorialised’ understanding of the Empire as a patchwork of enclosed geopolitical spaces within the Reich’s borders was evidently alien to pre-seventeenth-century Germans. This is clear from the problems contemporaries faced when sub-imperial authorities had to be precisely defined in spatial terms, as in the attempts to resolve divisions between Lutherans and Catholics from the 1520s onwards. The solution of the 1555 Diet of Augsburg that subordinates and subjects should adhere to the confession of their ruler, distilled in 1586 in the phrase cuius regio eius religio, provoked decades of judicial and juridical disputes. Neither regio nor Land referred to uncontested administrative zones into which all Germans could be sorted, for the simple reason that the Empire did not consist of discrete territorial blocs or ‘states’.35

It is, however, clear that in some regional contexts terra, territorium, or Land could have a more clearly spatial and governmental resonance, and these resonances gradually increased over time. Through the modalities explored in the sections below, some princes and cities exercised authority over explicitly bounded districts in this period. Administrative and legal sources sometimes employed terra or Land to describe small districts around a castle or settlement (also called Ämter, Kreise, Zirkel, Flecken, and Vogteien, among other terms), which were ruled by one or more lords represented by local officials.36 Slowly and fitfully, this ‘landed’ vocabulary came to be deployed in specific circumstances to describe larger agglomerations of rights and properties in the hand of one ruler or set of rulers, symbolically anchored to a princely dynasty that identified itself with a local toponymic title. This was the case with the accumulated possessions of Albrecht ‘Achilles’ (1414-1486), margrave of Ansbach and Kulmbach and later elector of Brandenburg. In seeking to give coherence to his splintered archipelago of assets and jurisdictions in Franconia, he dignified it with the term ‘our “territorum”[sic]’ in a 1449 letter.37 His enemies, who disputed some of Albrecht’s rights in the region, contested the applicability of such language. In 1461 Duke Ludwig ‘the Rich’ of Bavaria-Landshut argued of Albrecht ‘that he has no “land” […] and if he purports to have a “land”, it would be seemly for him to clarify what it is called’.38 At this time, Duke Ludwig claimed to rule a large portion of a relatively well-delineated political space that was sometimes called the Land Bayern. Ludwig’s contention was that Albrecht could not make a similar claim about his possessions in highly fragmented Franconia.

Such usages offer insight into the gap between ideal and reality in claims to rule a Land in this sense, that is, a cluster of rights and powers exercised by princely administrations in at least an approximately defined space – in other words, something approaching a ‘territory’. Even the dukes of Bavaria, who could argue that their patrimony constituted a Land in a way that other princes’ did not, did not exercise anything approaching uncontested authority within the putative boundaries of a single Bavarian duchy until well into the sixteenth century. Before 1506, even Bavaria consisted in practice of multiple separate ‘part-duchies’ under different warring branches of the Wittelsbach family.39 The unqualified word Land thus appeared rarely even in Bavarian sources, which in this period favoured more abstract (and less explicitly spatial) terms like ‘duchy’ and ‘principality’ (Herzogthum, Fuerstenthum), reserving Land- as a prefix for vassals and estates (Landsessen, Landschaft).40 Even in the second half of the 1300-1600 period, then, the closest approximations we have of concepts of ‘territory’ as imagined in the territorialisation narratives were strategically deployed claims (in the sense suggested by Elden), valuable as arguments with rival power wielders but always open to contestation, rather than stable features of political discourse and political life.

‘Territorial’ Structures? Political Economy, Lordship, and Administration

In the classic model of territorialisation, two forms of lordship were united under ‘territorial lords’ (Territorialherren) in the fourteenth to sixteenth centuries, amounting to their increasingly coherent power bases. Grundherrschaft, seigneurial rights and property over land and its inhabitants at the local level, continued to be exercised by a variety of lords, but these were increasingly ‘mediatised’ under the authority of the highest-ranking rulers (mostly princes). Gerichtsherrschaft, meanwhile, consisted of a cluster of ‘higher’ jurisdictional powers and regalian rights wielded by princes and others over lower-ranking lords and communities. Through the coercive and centralising agency of local officers and courtly, judicial, and fiscal institutions, the imperial elites wove these assets and rights together within spatially delineated zones, turning the German political landscape into a patchwork quilt of increasingly discrete and intensely ruled territories.41

This narrative of cohering ‘territorial’ formations is paradoxical, be-cause there is abundant evidence that the period 1300-1600, and even the two centuries that preceded it, saw the disaggregation and dispersal of even the smallest-scale clusters of rights and properties in the German politico-seigneurial landscape. The unitary manors (Villikationen) of earlier medieval Germany, to the extent that they ever truly existed in this form, had crumbled and segmented by around 1300, with a diverse array of lords of vastly diverging wealth and status having some stake in Grundherrschaft for the rest of the late medieval and early modern periods.42 ‘Higher’ fiscal, jurisdictional, and regalian powers and privileges within a given zone could be similarly divided, albeit among a narrower range of potential exercisers (mostly princes, the upper nobility, cities, and cathedral chapters and monasteries). Well into the sixteenth century, therefore, assets and powers ranging from the revenues from a mill to the right of safe conduct (Geleit) that were located in the same area could be in the hands of multiple independent lords.43 Only a small number of princely administrations towards the end of our period, such as Saxony and Bavaria, could claim at least an indirect authority over the most significant lands and rights within a demarcated zone that could meaningfully be called a territory in the sense implied by the secondary literature.

The fragmented character of lordship in the German lands was enabled by a financialised political economy in which any asset, revenue, or jurisdiction could be treated like a commodity and isolated, transferred to another party, and recombined within a new patrimony. The exchange of components of lordship was facilitated by sophisticated credit networks, in which not only urban patricians and merchants but also nobles played prominent roles as lenders to one another and to princes.44 There is growing evidence that a commercialised credit economy even extended to the level of tenant farmers.45 In this context, the building blocks of lordship could be transferred between and divided among any number of potentially autonomous owners and exercisers, in transactions ranging from simple sales to exchanges of loans for tenure of pledged assets, rights, or offices (Pfandschaften) or of fiefs (Lehen), not to mention transfers within elite familial networks through vehicles such as inheritances, dowries, and jointures.

Consequently, even at a very local level, the notion that the Holy Roman Empire was divided into political spaces ruled evenly by individual lords with growing monopolies of jurisdiction seems questionable. A perusal of registers of possessions and/or incomes (Urbare) compiled by princely and monastic regimes in these centuries underlines this point. For example, in 1427 the priory of Reichenbach in southern Germany produced an Urbar. Few of its possessions were entire villages. Instead, it owned hundreds of tiny fragments of land and buildings, with or without appertaining lower jurisdictions, often held in f ief by prominent villagers.46 Some of these holdings were co-ruled with otherwise autonomous authorities. The entry for Hochdorf near the river Neckar, for instance, states that the village court should hold two annual sessions, and that jurisdiction over them was held jointly (‘dieselben […] zway gericht seind gemein’) with the minor noble lords of Enzklösterle, such that they and the prior of Reichenbach wielded the judicial rod together (‘den stab gemein hand’).47 To complicate matters further, Reichenbach was a dependency of the imperial abbey of Hirsau, and advocatial rights over it were disputed between the counts of Eberstein, the margraves of Baden, and the counts (later dukes) of Württemberg.48 Who, then, was the ‘territorial lord’ of Hochdorf? The limitations of the territorialisation paradigm are clear in such situations.

Arguably the less densely populated north-eastern regions of Germany, which also had less developed traditions of communal government at the village level, tended to enable the f ief-holding nobility to exercise more cohesive and intensive control of spaces in and around settlements and their increasingly servile inhabitants, exploited under a regime dubbed Gutsherrschaft. Yet this did not translate automatically into unitary territorial power for the princes from whom these nobles held their fiefs. In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries more and more higher (e.g. capital) jurisdictions were alienated from the dukes of Mecklenburg to their noble estates, for instance.49 A recent study of Brandenburg has argued that the margraves’ authority over their putative northern possessions was largely symbolic, and would not rest on jurisdictional and fiscal structures buttressed from below by an obedient nobility until late in our period.50

Forms and configurations of tenure and off ice holding under secular and spiritual princes (and, less often, under city councils) could also mitigate against the formation of spatially coherent political authority, rather than contributing to ‘territorialisation’. Fiefs and pledges (Pfandschaften) issued by a prince could be held by vassals or subordinates who might simultaneously hold other parts of their patrimony from a different lord – a particularly common situation in regions such as the Upper Rhine and Franconia, where many imperially immediate actors existed in close proximity. In 1428 Count Palatine Ludwig III noted that ‘we and other princes, counts, barons, knights, and squires, and also urban communes, rub up against each other on many sides, and in places are almost mixed together’.51 A unitary and areal conception of power – an essential prerequisite of territorial authority as exercised within an enclosed and uncontested space – was difficult to maintain when one’s vassals or officers were simultaneously independent imperial nobles embedded in power-sharing leagues and knightly societies and serving other princes in similar capacities. Over time some noble families in the orbit of some princes (such as the dukes of Saxony) came to benefit from service at one specific court, exerting a centripetal effect within their networks, but this was by no means the case everywhere.52 Recent research has noted that some princes welcomed pluralistic tenure and office holding by their noble clients, since this opened informal opportunities for advantageous interpersonal contact with peers mediated through common vassals and officers.53

The most unambiguous trend towards greater coherence and consolidation can be detected in the ‘central’ institutions and organisms that developed around princely regimes. The court (curia, Hof) has been intensively studied as a social, political, and cultural entity that emerged in the Late Middle Ages and became the focal point of institutional continuity and expansion for German princely governments.54 High-ranking prelates led the way: the archbishops of Trier had advisory councils (Räte) and permanent chancery personnel by the fourteenth century, courtly ordinances and officers by the early fifteenth, and, by c. 1450, aulic courts of appeal (Hofgerichte) with increasing popularity among litigants in lower courts connected in some way to the ecclesiastical principality.55 Similar institutions crystallised around the dukes of Bavaria, Saxony, and Württemberg and the counts palatine on a slightly later timeline.56

These central institutions, particularly through their capacity to outlive individual princes, undoubtedly made it possible to think in the abstract about principalities and other political entities within the Holy Roman Empire, such as ‘the Palatinate’ (Pfalzgrafschaft) or the ‘Duchy of Bavaria’ (Herzogtum Bayern). These abstractions could have spatial content. For example, princely personnel sometimes defined the jurisdictions of higher courts or the applicability of tolls and irregular taxes in relation to topography and the borders of (typically piecemeal) districts and settlements.57 This partially ‘zonal’ authority was never uncontested, and was often in tension with the plural and overlapping nature of local power noted above; yet its existence at a conceptual level is undeniable. But did these political abstractions that developed out of central institutions equate to ‘territories’, as the territorialisation narratives have def ined them? We have seen that this was not straightforwardly the case in contemporary terminology. For secular principalities, dynastic dynamics and the need to provide for heirs, often by dividing patrimony, repeatedly entailed the partition of ‘central’ jurisdictional and fiscal regimes and the spaces in which they were supposed to hold sway, leading to multiple princely courts with their own institutions.58 Treaties and alliances of inheritance, partition, or condominium within a dynastic zone could be brokered, often with input from councillors or estates, and to this extent we can see that the abstractions of Land, Herzogtum, etc., had some purchase as labels for groups of elites with a stake in a princely regime. These were, however, interpersonal (we might say ‘corporative’, ‘multilateral’, or ‘associative’) conceptions of the political units created by German princes, rather than spatial/territorial ones.

Indeed, far from constituting bureaucratised organs intent on demarcating and controlling territorially conceived spaces, the courtly and representative institutions of late medieval and sixteenth-century principalities were largely ad hoc meeting points between princes and other regional elites. In contemporary terms (often found in the treaties that framed relations between the ‘members’ or ‘estates’ of principalities), these institutions underpinned reciprocal ties between prominent political actors justif ied in relation to the common good, custom, and justice, and functioned as sites for the performance of social and ritual processes through which these ties were maintained.59 Often the political actors who participated in regional diets and princely councils and other courtly institutions were not straightforward subjects whose actions fit the narrative of cohesive territorialisation. In this respect a tendency to focus disproportionately on the appointment of small numbers of jurists educated in civil law, ostensibly as harbingers of rationalisation and territorial state formation in these centuries, has missed the enduring importance of princely institutions as nodal points in aristocratic networks.60

Princes’ staff and councillors could be nobles with substantial autonomy, or even imperially immediate neighbours who, though less powerful and influential and lower in the social hierarchy, were de jure peers of the princes they counselled. The Rat (council) of the fifteenth-century counts and dukes of Württemberg, for instance, included at various times the prince-bishops of Constance and Augsburg and members of the independent comital houses of Helfenstein, Zollern, and Oettingen.61 The counts palatine signed repeated ‘protection treaties’ (Schirmverträge) with the bishops of Speyer in this period, some of whom even served as chancellors of the Palatinate, yet the properties and jurisdictions of the prince-bishopric remained formally independent until the nineteenth century.62 To describe the political entities in the Holy Roman Empire primarily in the language of geographical or political space – as ‘territories’ – risks missing these fundamental interpersonal ties and their attendant socio-economic and cultural contexts, which structured lordship and administration into overlapping and dynamically disaggregating-then-recombining configurations rather than discrete units, at both local and central levels.

Conclusion: The Limitations of Territorial Concepts and the Importance of the Imperial Framework

In the abundant sources that survive from the fourteenth- to sixteenth-century German localities, it is clear that the authority of political actors could be conceived in theory and wielded in practice in ways that related explicitly to spatially defined zones. Mostly these were small in scale: long-standing customary village jurisdictions, or official districts (Ämter, etc.) that became fitfully more consolidated for fiscal and judicial purposes. We have also seen that even at this very local level, such notional units could in practice be fragmented and governed through a plurality of lords and agencies. By the mid-fifteenth century, a larger-scale sense of terra, territorium, or Land could also be deployed to refer to and claim coherence for the accumulated possessions of a powerful prince. Again, however, the unity and integration claimed for such political spaces was more rhetorical than tangible in practice, and always had to be negotiated with subsidiary actors, who might have stakes in multiple other princely or urban power bases. Because these recognisably spatial aspects of government below the level of the imperial monarchy did exist in the German lands, and because of the long tradition of applying ‘territorial’ concepts to them, the term ‘territory’ is likely to endure as a label for the constituent parts of the Empire, particularly in general-audience and synthetic literature.

Yet, abstract concepts that encapsulated an array of dynastic, noble, or custom- or estate-based solidarities and relationships predominate in the sources over unqualifiedly territorial vocabulary – for good reason, as we have seen from this brief survey of the complex contours of Germany’s political landscape in this period. As the impossibility of reconciling the evidence of disaggregation and overlap with the Territorialstaat paradigm has become more apparent, it has come under sustained scholarly attack. Before we consider whether any definition of ‘territory’ is helpful, it has to be acknowledged that the long-standing narrative of territorialisation as a kind of unitary state formation simply does not take account of the fragmented-yet-overlapping configuration of the German lands in this period, nor of the variety of religious, aristocratic, and communitarian logics that motivated their inhabitants. A neat territorium clausum as imagined by eighteenth-century jurists and subsequent historians cannot be found even in the more consolidated principalities such as Brandenburg, Saxony, or Bavaria before 1600.

This lack of exclusively spatially defined power begs the question of what other frameworks, conceptual and material, gave coherence to local and regional politics in the German lands in this period. Here the renewed focus on the Holy Roman Empire as an overarching polity since the 1970s, liberated from some of the nationalist baggage that had accompanied its study in earlier eras, furnishes persuasive answers and models. Many of the governmental functions managed ‘internally’ within a conventionally defined political territory operated at ‘trans-’ or ‘supra-territorial’ levels in Germany.63 In particular, new research has emphasised the plethora of interactions that princes, nobles, and cities engaged in with each other, often within treaty-bound leagues, alliances, and other associations with varying degrees of connection to the Empire’s overarching institutions. These could regulate spheres of joint governmental activity as diverse as troop provisioning in times of war and the value of coinage.64 Landfrieden (peacekeeping) is a clear example. While stemming in theory from the monarchy’s obligations and prerogatives, and increasingly also from ordinances issued at imperial diets, late medieval defence of travellers and prosecution of certain kinds of criminals or troublemakers (particularly declarers of feuds) was organised within regional alliances of imperially immediate authorities. From the early sixteenth century these alliances were supplemented or supplanted by the horizontally organised imperial circles (Reichskreise) that transcended any individual lord.65 Similarly, judicial activity involving princes, nobles, and cities, and sometimes even their more humble subjects, tended to take the form of arbitration by political peers, later formalised and juridicised in collectively managed imperial courts like the Reichskammergericht.66

Even the wealthiest princes from the most prestigious houses in Germany were also members and estates of the Empire and vassals of its monarch. The Reich was not only the ultimate symbolic source of the political legitimacy that they claimed, but a dynamic superstructure within which they had to engage with other imperial estates, particularly when problems arose (such as the security of shared roads, external invasions from the east and west, and internal confessional strife) which were insurmountable for any individual lord. The ties between the authorities in the Empire’s heartlands thus became increasingly enmeshed within its developing institutions as this period wore on, crystallising a multilayered and multilateral structure for a variety of governmental functions that mitigated against the formation of unitary territorial states, as the less subtle territorialisation narratives posit.67

What vocabulary should we use to apprehend the subsidiary components of a pre-modern polity of this kind, in which forms and configurations of authority could legitimately be claimed – and jointly exercised – by a diverse cast of actors at multiple intersecting levels, from portions of villages and castles to the imperial diets and judicial bodies, via princely courts and municipal governments? The present author’s preference, unwieldy though it may seem to some, is to employ generic terms such as ‘status holders’, ‘political actors’, ‘entities’, or ‘imperial elites’, which can encompass the power bases of every rank of prince, and a spectrum of nobles, towns, and communes too. This leaves open the possibility of specifying that claims to authority could have spatial, even geopolitical (and hence potentially ‘territorial’) dimensions in specific situations, without overriding the many non-space-contingent ways in which the inhabitants of the German lands conceived of and exercised power. If, following Stuart Elden, we seek to move beyond viewing territorial power as a matter of ‘bounded space’ and see claims to rule a territorium, such as that made by Margrave Albrecht Achilles in 1449, as deployments of a ‘calculative category’ that was situationally useful but not the only or primary understanding of authority in this period, the word ‘territory’ can find a meaningful place in the terminology of the historian of pre-modern Germany.68 But, in the case of the German-speaking regions of the Holy Roman Empire at least, even an emerging calculated discourse of the Land/terra/territorium qua ‘political technology’ was only one of several logics of power within a broader framework, whose constituent parts cannot be studied in isolation from it.

Appendix

Endnotes

- ‘Omnes autem predicti principes nobilesque in auxilium ministeriumque sacri imperii sunt instituti, ex quibus terrena perfectissime constituitur monarchia. Quorum proprium est of f icium rempublicam in terris sibi commissis […] regere.’ Andlau, Kaiser und Reich, p. 258.

- Ibid., pp. 150-168.

- Die Chronik Heinrichs Taube, p. 58.

- E.g. Deutsche Reichstagsakten. Ältere Reihe, vol. 22, p. 250; Deutsche Reichstagsakten unter Kaiser Karl V., pp. 115-117.

- E.g. Urkunden zur Geschichte des Schwäbischen Bundes, vol. 1, p. 213.

- Notably Moraw, Von offener Verfassung, pp. 161, 236.

- Bahlcke, Landesherrschaft, pp. 7-8, 56-58.

- See ‘Territorium’, in Grosses vollständiges Universal-Lexikon, vol. 42, cols. 1139-1140.

- Elden, ‘Land, Terrain, Territory’, pp. 810-812.

- See Whaley, Germany, vol. 2, pp. 96-102.

- For what follows, see Scales, The Shaping of German Identity, pp. 1-97.

- For a recent overview, see Reinle, ‘“Meistererzählungen”’, pp. 61-64.

- On the Territorialstaat narrative, and for a critique of these scholarly traditions, see Groten, ‘Erforschung’, pp. 192-195.

- See Werner, ‘Zur Geschichte des Faches’.

- Gerlich, Landeskunde, p. 284.

- Rutz, Beschreibung, p. 59.

- Schulze, Staatsrecht, pp. 233-235.

- Mayer, ‘Ausbildung’.

- Brunner, Land und Herrschaft.

- For instance, the European Science Foundation funded the comparative ‘Origins of the Modern State in Europe’ programme from the 1980s, yielding several comparative volumes: https://global.oup.com/academic/content/series/o/the-origins-of-the-modern-state-in-europe-13th-to-18th-centuries-omse (accessed 12 January 2020).

- Bahlcke, Landesherrschaft, pp. 1-8, 56-76.

- For some influential post-war studies within this model, see Patze, Territorialstaat.

- A perspective summarised in Moraw and Press, ‘Probleme’. See also Moraw, Von offener Verfassung.

- Stollberg-Rilinger, Emperor’s Old Clothes.

- Winkelmann, Brandenburg; Eiler, Landesherrschaft.

- For overviews, see Schubert, Territorium, pp. 19-26; Heinemeyer, Reich und Region, pp. 20-46; Rutz, Beschreibung, pp. 58-75.

- Schubert, Territorium, pp. 59-61.

- Ibid., pp. 52-58.

- Reinle, ‘“Meistererzählungen”’, pp. 62-64.

- Rutz, Beschreibung, esp. pp. 58-104, 222-229, 456-464.

- Schubert, ‘Begriff “Land”’, pp. 22-23.

- Bünz, ‘Landesbegriff’.

- See, e.g., Deutsche Reichstagsakten. Ältere Reihe, vol. 16, p. 401.

- Hardy, Associative Political Culture, pp. 256-259, with further references.

- Bahlcke, Landesherrschaft, p. 61.

- Schubert, ‘Begriff “Land”’, pp. 17-21.

- Quoted in Zeilinger, ‘Anwesenheit’, p. 173.

- Quoted in Schubert, ‘Begriff “Land”’, p. 17.

- Schubert, Territorium, pp. 23-24; Bahlcke, Landesherrschaft, pp. 78-79.

- E.g. Krenner, Landtags-Handlungen, vol. 15, passim, esp. pp. 338-381.

- See, e.g., the contributions in Jeserich, Verwaltungsgeschichte.

- Rösener, ‘Grundherrschaft’, pp. 62-68.

- For examples from Upper Germany, see Hardy, Associative Political Culture, chap. 4. For a specific example of safe conduct and other rights held by others in Nuremberg’s sphere of influence, see Rutz, Beschreibung, p. 428.

- Zmora, ‘State-Making’.

- Ghosh, ‘Commercialisation’.

- Das älteste Urbar, passim.

- Ibid., p. 140.

- Ibid., pp. xiii-xiv.

- Scott, Society and Economy, pp. 182-188.

- Winkelmann, Brandenburg, pp. 314-321.

- Quoted in Schubert, Territorium, p. 6.

- Schneider, ‘“Erhbare Mannschaft”’.

- Heinemeyer, Reich und Region, pp. 529-534.

- See the long-running Residenzforschung series edited by the Residenzen-Kommission der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Göttingen: https://www.thorbecke.de/residenzenforschung-c-310_138_248.html (accessed 12 January 2020).

- Holbach, ‘Trier’.

- See Schubert, Territorium, pp. 67-70.

- For examples of this in the Prince-Bishopric of Basel, see Weissen, ‘An der stuer’.

- Spieß, Familie.

- See Hardy, Associative Political Culture, chaps 7-8.

- See Widder, Kanzleien, esp. chap. 2.

- Hardy, Associative Political Culture, p. 171.

- E.g. Bishop Matthias Ramung; see Widder, Kanzleien, pp. 400-419.

- Bahlcke, Landesherrschaft, p. 101.

- Hardy, Associative Political Culture, chaps 5-6, 8.

- Ibid., pp. 102-104, 148-150, 240-243, with further references.

- Ibid., pp. 244-252.

- See Moraw’s influential concept of gestaltete Verdichtung in the Empire: Moraw, Von offener Verfassung, pp. 411-421.

- Elden, ‘Land, Terrain, Territory’, pp. 799, 810-812.

Bibliography

- Andlau, Peter von, Kaiser und Reich. Libellus de Cesarea monarchia, ed. by Rainer Müller (Frankfurt a. M.: Insel, 1998).

- Bahlcke, Joachim, Landesherrschaft, Territorien und Staat in der Frühen Neuzeit (Munich: Oldenbourg, 2012).

- Baierische Landtags-Handlungen in den Jahren 1429 bis 1513, ed. by Franz von Krenner, 18 vols (Munich: F.S. Hübschmann, 1803-1805).

- Brunner, Otto, Land und Herrschaft. Grundfragen der territorialen Verfassungs-geschichte Österreichs im Mittelalter, 5th ed. (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1965 [first published 1939]).

- Bünz, Enno, ‘Das Land als Bezugsrahmen von Herrschaft, Rechtsordnung und Identitätsbildung: Überlegungen zum spätmittelalterlichen Landesbegriff ’, in Spätmittelalterliches Landesbewußtsein in Deutschland, ed. by Matthias Werner (Ostfildern: Thorbecke, 2005), pp. 53-92.

- Das älteste Urbar des Priorats Reichenbach von 1427, ed. by Regina Keyler (Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 1999).

- Deutsche Reichstagsakten. Ältere Reihe, ed. by Julius Weizsäcker et al., 22 vols (Gotha: Perthes/Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1867-2013).

- Deutsche Reichstagsakten unter Kaiser Karl V. Der Reichstag zu Augsburg 1555, ed. by Rosemarie Aulinger et al. (Munich: Oldenbourg, 2009).

- Die Chronik Heinrichs Taube von Selbach, ed. by Harry Bresslau, Monumenta Germaniae Historica. Scriptores rerum Germanicarum. Nova series, vol. 1 (Berlin: Weidmann, 1922).

- Eiler, Klaus, Stadtfreiheit und Landesherrschaft in Koblenz: Untersuchungen zur Verfassungsentwicklung im 15. und 16. Jahrhundert (Wiesbaden: Steiner, 1980).

- Elden, Stuart, ‘Land, Terrain, Territory’, Progress in Human Geography 34, no. 6 (2010), 79 9 – 817.

- Gerlich, Alois, Geschichtliche Landeskunde des Mittelalters. Genese und Probleme (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1986).

- Ghosh, Shami, ‘Rural Commercialisation in Fourteenth-Century Southern Germany: The Evidence from Scheyern Abbey’, Vierteljahrschrift für Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte 104, no.1 (2017), 52-77.

- Grosses vollständiges Universal-Lexikon aller Wissenschaf ften und Künste, 64 vols (Halle/Leipzig: Johann Heinrich Zedler, 1732-1754).

- Groten, Manfred, ‘Die Erforschung des hochmittelalterlichen Adels im Rheinland. Bilanz und Perspektiven’, in Verortete Herrschaft. Königspfalzen, Adelsburgen und Herrschaftsbildung in Niederlothringen während des frühen und hohen Mittelalters, ed. by Jens Lieven et al. (Bielefeld: Verlag für Regionalgeschichte, 2014), pp. 191-210.

- Hardy, Duncan, Associative Political Culture in the Holy Roman Empire: Upper Germany, 1346-1521 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018).

- Heinemeyer, Christian, Zwischen Reich und Region im Spätmittelalter. Governance und politische Netzwerke um Kaiser Friedrich III. und Kurfürst Albrecht Achilles von Brandenburg (Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, 2017).

- Holbach, Rudolf, ‘Trier, Erzbischöfe von’, in Höfe und Residenzen im spätmittelalter-lichen Reich. Ein dynastisch-topographisches Handbuch, ed. by Werner Paravicini et al., 2 vols (Ostfildern: Jan Thorbecke, 2003), vol. 1, pp. 421-427.

- Jeserich, Kurt, ed., Deutsche Ver waltungsgeschichte. Band I. Vom Spätmittelalter bis zum Ende des Reiches (Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1983).

- Mayer, Theodor, ‘Die Ausbildung der Grundlagen des modernen deutschen Staates im Mittelalter’, in Herrschaft und Staat im Mittelalter, ed. by Hellmut Kämpf (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1956 [first published 1939]), pp. 284-331.

- Moraw, Peter, Von of fener Verfassung zu gestalteter Verdichtung. Das Reich im späten Mittelalter 1250 bis 1490 (Berlin: Propyläen, 1985).

- Moraw, Peter, and Volker Press, ‘Probleme der Sozial- und Verfassungsgeschichte des Heiligen Römischen Reiches im späten Mittelalter und in der Frühen Neuzeit (13 .-18 . Jahrhundert)’, Zeitschrift für historische Forschung 2 (1975), 95-108.

- Patze, Hans, ed., Der deutsche Territorialstaat im 14. Jahrhundert, 2 vols (Sigmaringen: Thorbecke, 1970-1971).

- Reinle, Christine, ‘“Meistererzählungen” und Erinnerungsorte zwischen Landes- und Nationalgeschichte. Überlegungen anhand ausgewählter Beispiele’, in Handbuch Landesgeschichte, ed. by Werner Freitag et al. (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2018), pp. 56-71.

- Rösener, Werner, ‘Die Grundherrschaft als Forschungskonzept: Strukturen und Wandel der Grundherrschaft im deutschen Reich (10.-13. Jahrhundert)’, Zeitschrift der Savigny-Stiftung für Rechtsgeschichte: Germanische Abteilung 1 29 (2012), 4 1- 75.

- Rutz, Andreas, Die Beschreibung des Raums. Territoriale Grenzziehungen im Heiligen Römischen Reich (Cologne/Weimar/Vienna: Böhlau, 2018).

- Scales, Len, The Shaping of German Identity: Authority and Crisis, 1245-1414 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012).

- Schneider, Joachim, ‘“Ehrbare Mannschaft”: Die Beziehungen zwischen den sächsischen Herzögen und dem Niederadel’, in (Un)Gleiche Kurfürsten? Die Pfalzgrafen bei Rhein und die Herzöge von Sachsen im späten Mittelalter (1356-1547), ed. by Jens Klingner and Benjamin Müsegades (Heidelberg: Winter, 2017), pp. 207-220.

- Schubert, Ernst, ‘Der rätselhafte Begriff “Land” im späten Mittelalter und in der frühen Neuzeit’, Concilium medii aevi 1 (1998), 15-27.

- Schubert, Ernst, Fürstliche Herrschaft und Territorium im späten Mittelalter, 2nd ed. (Munich: Oldenbourg, 2006).

- Schulze, Hermann, Das preussische Staatsrecht auf Grundlage des deutschen Staatsrechts (Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1872).

- Scott, Tom, Society and Economy in Germany, 1300-1600 (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2002).

- Spieß, Karl-Heinz, Familie und Verwandtschaft im deutschen Hochadel im Spätmittelalter 13. bis Anfang 16. Jahrhunderts, 2nd ed. (Stuttgart: Steiner, 2015).

- Stollberg-Rilinger, Barbara, The Emperor’s Old Clothes: Constitutional History and the Symbolic Language of the Holy Roman Empire, trans. by Thomas Dunlap (New York/Oxford: Berghahn, 2015).

- Urkunden zur Geschichte des schwäbischen Bundes (1488-1533), ed. by Karl Klüpfel, 2 vols (Stuttgart, 1846-1853).

- Weissen, Kurt, ‘An der stuer ist ganz nuett bezalt’. Landesherrschaft, Wirtschaft und Verwaltung in den fürstbischöf lichen Ämtern in der Umgebung Basels (1435-1525) (Basel: Helbing & Lichtenhahn, 1994).

- Werner, Matthias, ‘Zur Geschichte des Faches’, in Handbuch Landesgeschichte, ed. by Werner Freitag et al. (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2018), pp. 3-23.

- Whaley, Joachim, Germany and the Holy Roman Empire, 2 vols (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012).

- Widder, Ellen, Kanzler und Kanzleien im Spätmittelalter: eine Histoire croisée fürstlicher Administration im Südwesten des Reiches (Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 2016).

- Winkelmann, Jan, Die Mark Brandenburg des 14. Jahrhunderts: markgräf liche Herrschaft zwischen räumlicher ‘Ferne’ und politischer ‘Krise’ (Berlin: Lukas, 2011).

- Zeilinger, Gabriel, ‘Anwesenheit und Abwesenheit. Hof feste, Kriege und die “Verdichtung” des Reichs im 15. Jahrhundert’, in Stand und Perspektiven der Sozial- und Verfassungsgeschichte zum römisch-deutschen Reich. Der Forschungseinf luss Peter Moraws auf die deutsche Mediävistik, ed. by Christine Reinle (Affalterbach: Didymos, 2016), pp. 165-176.

- Zmora, Hillay, ‘Princely State-Making and the “Crisis of the Aristocracy” in Late Medieval Germany’, Past & Present 153, no. 1 (1996), 37-63.

Chapter 1 (29-52) from Constructing and Representing Territory in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe, edited by Mario Damen and Kim Overlaet (Amsterdam University Press, 12.08.2021), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported license.