The foundation of ICE in 2003 marked more than a bureaucratic reorganization. It signaled the redefinition of immigration enforcement.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Bureaucratizing Fear in the Post-9/11 State

In March 2003, amid the swelling machinery of post-9/11 homeland security, the United States formally created a new agency under the Department of Homeland Security (DHS): Immigration and Customs Enforcement, more commonly known as ICE. On paper, the agency was a consolidation of existing enforcement powers (customs, immigration investigations, and interior policing) gathered from the once-monolithic Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) and U.S. Customs Service. But in function, ICE became something more: a symbol of the federal government’s reorientation of immigration as a matter of counterterrorism, domestic surveillance, and securitized identity.

The creation of ICE was not an administrative inevitability. It was a political act, born out of fear and framed through a lens of crisis. This essay traces the conceptual and institutional foundations of ICE, examines the tensions between immigration enforcement and civil liberties embedded in its structure, and reflects on the deeper historical shift that ICE both embodies and extends: the transformation of immigration policy from a system of regulatory governance to a theater of internal control.

The story of ICE is not merely about a federal agency. It is about the migration of security logic into civil life, the inheritance of bureaucratic tools from older enforcement regimes, and the emergence of a new moral vocabulary in which borders are imagined not as geographic lines, but as moving targets embedded within the national interior.

INS to ICE: From Management to Militarization – the Demise of the INS and the DHS Reorganization

Prior to 2003, the Immigration and Naturalization Service operated under the Department of Justice and had jurisdiction over both the administrative and enforcement aspects of immigration policy. The INS was a sprawling entity, responsible for border control, visa processing, refugee resettlement, naturalization, detention, and deportation. It had long been criticized for inefficiency, bureaucratic bloat, and conflicting mandates. Yet the attacks of September 11, 2001 provided the political catalyst for its dismemberment.

In November 2002, Congress passed the Homeland Security Act, which created the Department of Homeland Security and transferred 22 federal agencies under its control. The INS was dissolved, and its functions split among three new bodies: U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), responsible for processing lawful applications; Customs and Border Protection (CBP), in charge of ports of entry and border enforcement; and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), tasked with interior enforcement and criminal investigations.1

While all three agencies inherited elements of the INS, ICE was imbued with a distinct mandate. It was envisioned not as a facilitator of legal immigration, but as a hunter of threats, real or imagined, within the borders of the United States. Its dual focus on immigration violations and customs enforcement marked a conceptual fusion: immigrants were no longer merely subjects of administrative law, but of criminal suspicion. This fusion would have far-reaching implications.2

Constructing the “Interior Border”: ICE and the Logic of Inward Surveillance – the New Architecture of Enforcement

ICE was designed to enforce federal immigration laws within the interior of the United States, but its activities quickly expanded into complex realms of counterterrorism, cybercrime, and transnational criminal networks. The agency’s Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) division grew to include more than 6,000 special agents and took the lead on large-scale operations targeting everything from human trafficking to intellectual property theft. But the agency’s public identity came to be shaped most prominently by its Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO) arm, which focuses on detaining and deporting undocumented immigrants.3

With sweeping authority to conduct raids, execute administrative warrants, and access a growing array of federal databases, ICE became an instrument of interior border creation. Unlike CBP, which operates at ports and physical borders, ICE deployed its power in the workplaces, homes, schools, and courts of American cities. Deportation, once largely reactive, became proactive. National security became a rationale for interior visibility.4

The transformation was not only operational but cultural. Through rhetoric that linked immigration violations with terrorism and crime, ICE reframed the presence of undocumented immigrants as an existential threat. The immigrant ceased to be a neighbor or worker and became a suspect. This reconceptualization blurred distinctions between civil and criminal enforcement and introduced a surveillance logic to spaces far removed from traditional borders.5

Continuities of Control: ICE and the Inheritance of Past Enforcement

The Shadow of Operation Wetback and Cold War Logics

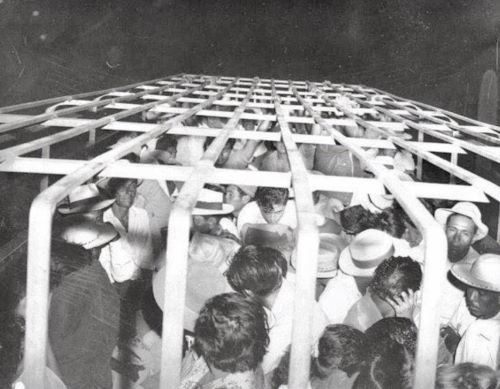

Though ICE was born in the post-9/11 era, it did not invent interior immigration enforcement. In 1954, the Eisenhower administration launched Operation Wetback, a mass deportation campaign that removed over a million people, primarily Mexican nationals, through tactics that included military-style raids, racial profiling, and forced removals with little due process. While ICE did not replicate this program outright, its structure revived its logic: that national security justified sweeping immigration enforcement untethered from judicial oversight.6

Similarly, during the Cold War, the INS and FBI cooperated on programs that surveilled immigrant communities suspected of communist sympathies. ICE, with its hybrid customs and immigration mission, inherited the same flexibility. It could pursue visa overstays, undocumented labor, or vague threats to “critical infrastructure” with equal vigor. The breadth of its mandate, coupled with limited public accountability, revived long-standing patterns of racialized policing under new banners.7

Detention, Contracting, and the Expansion of the Carceral State

ICE’s approach to immigration detention also built upon older legacies. The federal government had long relied on detention as a tool of immigration control, but ICE institutionalized it through contracts with private prison corporations and local jails. The agency’s daily detention population exploded from around 20,000 in the early 2000s to over 50,000 by the end of the decade.8

These facilities, often located in remote areas, operated with minimal transparency and were plagued by allegations of abuse, medical neglect, and due process violations. Civil detention in ICE custody came to resemble criminal incarceration, even though immigration offenses are civil infractions under U.S. law. The convergence of enforcement and punishment underscored the deeper ideological shift: immigrants were not being regulated, but punished.9

Politics of Visibility: ICE in the Public Imagination – from Administrative Agency to Political Symbol

ICE’s emergence coincided with a broader transformation in the politics of immigration. It became a lightning rod in debates over national identity, race, labor, and sovereignty. Public raids, high-profile removals, and viral videos of separated families made ICE one of the most publicly visible federal agencies, despite its largely bureaucratic origins.

Supporters hailed ICE as a bulwark against lawlessness and porous borders. Detractors described it as a rogue agency, immune to oversight and animated by xenophobia. Activist campaigns such as “Abolish ICE” emerged in response to the agency’s high-profile role in family separations under the Trump administration. Yet even under earlier presidents, ICE’s reach and authority had expanded steadily.

Its visibility became its paradox. Unlike the FBI or CIA, which operate largely in secrecy, ICE was both everywhere and exposed. Its actions could be filmed, its failures documented, its agents confronted. But its bureaucratic design insulated it from rapid reform. The result was a structural impasse: a deeply politicized agency nested within a vast federal hierarchy, subject to fierce scrutiny but also embedded in national security orthodoxy.10

Conclusion: The Homeland Turn and the Future of Enforcement

The foundation of ICE in 2003 marked more than a bureaucratic reorganization. It signaled the redefinition of immigration enforcement as a core component of homeland security. The agency was constructed in the image of a state that viewed mobility as threat, identity as suspicion, and borders as internal lines to be defended rather than managed.

In this framework, the immigrant body became a site of governance, not through integration or adjudication, but through surveillance, detention, and removal. ICE fused old enforcement tools with new security rationales, inherited practices of racialized control, and operated under statutory authorities that often blurred the lines between civil and criminal power.

The challenge for scholars and citizens alike is not simply to debate ICE’s legality or efficiency. It is to interrogate the vision of national belonging and control that its structure reflects. ICE was not inevitable. It was chosen. And its future depends not only on politics, but on the public’s willingness to imagine immigration enforcement as something other than a war fought within.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Department of Homeland Security, Homeland Security Act of 2002, Pub. L. No. 107-296, 116 Stat. 2135.

- Doris Meissner et al., “Immigration Enforcement in the United States: The Rise of a Formidable Machinery,” Migration Policy Institute (January 2013), 11–15.

- U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, “Overview,” https://www.ice.gov/about-ice.

- César Cuauhtémoc García Hernández, Migrating to Prison: America’s Obsession with Locking Up Immigrants (New York: The New Press, 2019), 32–38.

- Naomi Paik, Rightlessness: Testimony and Redress in U.S. Prison Camps Since World War II (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016), 121–135.

- Mae M. Ngai, Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004), 167–172.

- Kelly Lytle Hernández, Migra!: A History of the U.S. Border Patrol (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010), 205–210.

- Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC), “Immigration and Customs Enforcement Detention,” https://trac.syr.edu/immigration/detention/.

- Emily Ryo and Ian Peacock, “The Landscape of Immigration Detention in the United States,” American Immigration Council (December 2018), 5–8.

- Tina Vasquez, “Abolish ICE: Beyond a Slogan,’” The New York Review of Books, October 10, 2018.

Bibliography

- Department of Homeland Security. Homeland Security Act of 2002. Pub. L. No. 107-296, 116 Stat. 2135.

- García Hernández, César Cuauhtémoc. Migrating to Prison: America’s Obsession with Locking Up Immigrants. New York: The New Press, 2019.

- Hernández, Kelly Lytle. Migra!: A History of the U.S. Border Patrol. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010.

- Meissner, Doris, et al. “Immigration Enforcement in the United States: The Rise of a Formidable Machinery.” Migration Policy Institute, January 2013.

- Ngai, Mae M. Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004.

- Paik, A. Naomi. Rightlessness: Testimony and Redress in U.S. Prison Camps Since World War II. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016.

- Ryo, Emily, and Ian Peacock. “The Landscape of Immigration Detention in the United States.” American Immigration Council, December 2018.

- Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC). “Immigration and Customs Enforcement Detention.” https://trac.syr.edu/immigration/detention/.

- U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. “Overview.” https://www.ice.gov/about-ice.

- Vasquez, Tina. “Abolish ICE: Beyond a Slogan” The New York Review of Books, October 10, 2018.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.23.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.