It was established in the Ottoman Empire in 1881 as a “Christian utopian society”.

Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Family Tragedy

Overview

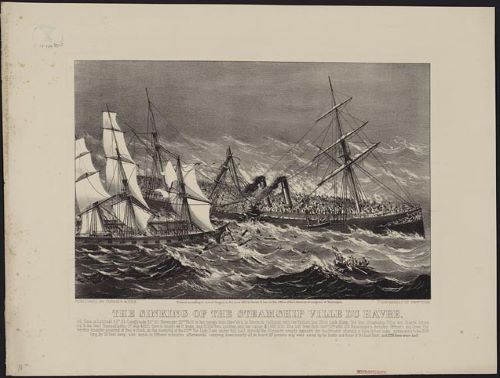

In 1871, Horatio Spafford, a prosperous lawyer and devout Presbyterian church elder and his wife, Anna, were living comfortably with their four young daughters in Chicago. In that year the great fire broke out and devastated the entire city. Two years later the family decided to vacation with friends in Europe. At the last moment Horatio was detained by business, and Anna and the girls went on ahead, sailing on the ocean liner S.S. Ville de Havre. On November 21, 1873, the liner was rammed amid ship by a British vessel and sank within minutes. Anna was picked up unconscious on a floating spar, but the four children had drowned.

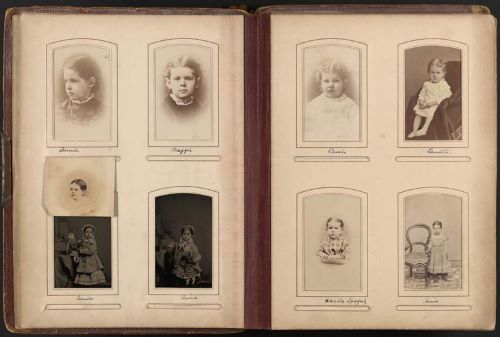

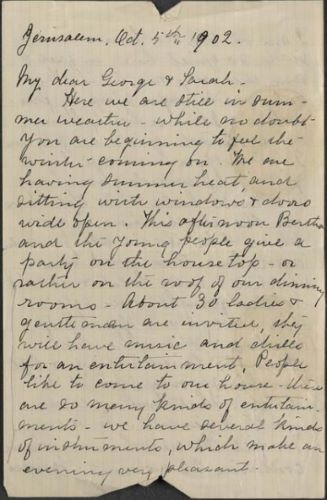

Spafford Family Album

The Spafford daughters, Annie, Maggie, Bessie, and Tanetta (top row, left to right) drowned when the S.S. Ville du Havre sank after it was hit by a British vessel en route to Europe in November 1873. A fellow survivor of the collision, Pastor Weiss, recalled Anna saying, “God gave me four daughters. Now they have been taken from me. Someday I will understand why.” The Spafford’s son Horatio (bottom row second from right), born three years after the tragedy, died in 1880 at age four.

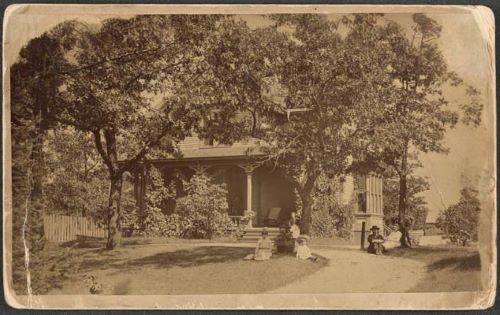

The Spafford Cottage at Lake View, Chicago

At their home in a north side suburb of Chicago, the Spaffords hosted and sometimes financially supported many guests. Horatio had been active in the abolitionist crusade and the cottage was a meeting place for activists in the reform movements of the time such as Frances E. Willard, president of the National Women’s Christian Temperance Union, and evangelical leaders like Dwight Moody, who ignited a religious revival in America and Europe.

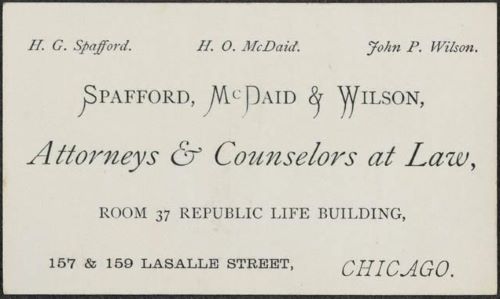

Spafford, a senior partner in a thriving law firm, invested in real estate north of an expanding Chicago in the spring of 1871. When the Great Fire of Chicago reduced the city to ashes in October of the same year, it also destroyed Spafford’s sizable investment.

Sinking of the Ville du Havre

In 1873, to benefit his wife’s health, Spafford planned an extended stay in Europe for his family. At the last moment Spafford was detained by real estate business, but Anna and the four girls sailed to Paris on the steamer Ville du Havre. Within twelve minutes on November 21, 1873, the luxury steamer sank in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean after being rammed by the British iron sailing ship the Lochearn.

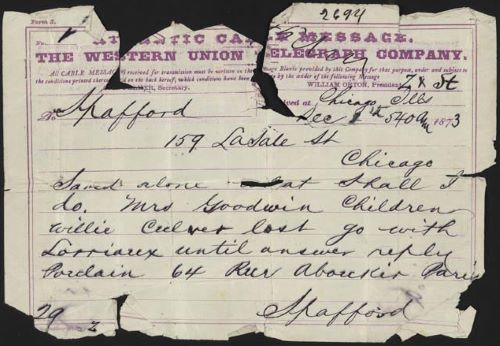

Anna’s Telegram to Horatio

Anna was picked up unconscious by the crew of the Lochearn, which itself was in danger of sinking. Fortunately, the Trimountain, a cargo sailing vessel, arrived to save the survivors. Nine days after the shipwreck Anna landed in Cardiff, Wales, and cabled Horatio, “Saved alone. What shall I do…”

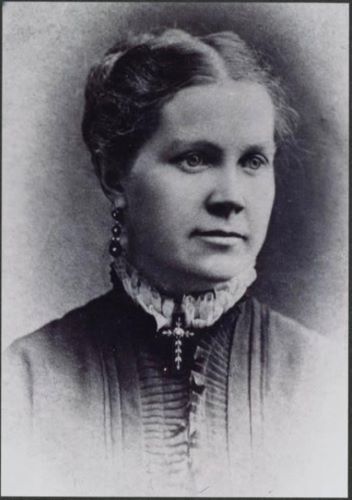

Horatio and Anna Spafford, ca. 1873

Anna Larssen, later Americanized to Lawson, was born in Stavanger, Norway, in 1842. Horatio was immediately attracted by Anna’s beauty and intelligence when she attended his Sunday school class in Chicago.

When Horatio realized that Anna, fourteen years younger than he, was only fifteen, he arranged for three years tuition at a boarding school near Chicago before the idea of marriage could be discussed. The couple married in 1861.

“It Is Well with My Soul”

After receiving Anna’s telegram, Horatio immediately left Chicago to bring his wife home. On the Atlantic crossing, the captain of his ship called Horatio to his cabin to tell him that they were passing over the spot where his four daughters had perished. He wrote to Rachel, his wife’s half-sister, “On Thursday last we passed over the spot where she went down, in mid-ocean, the waters three miles deep. But I do not think of our dear ones there. They are safe, folded, the dear lambs.”

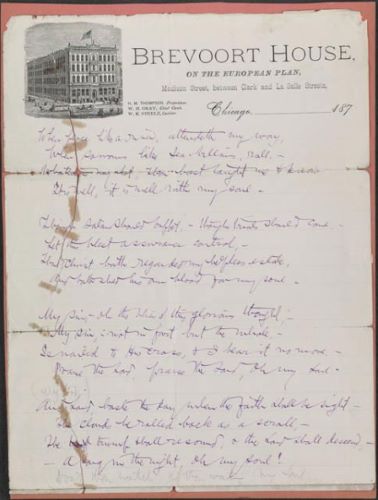

Horatio wrote this hymn, still sung today, as he passed over their watery grave.

On to Jerusalem

Overview

The Spaffords did their best to put together their shattered lives back in Chicago. In 1878, a daughter, Bertha, was born and, two years later, a son Horatio. After an epidemic of scarlet fever broke out and their baby son died, it seemed that the Spaffords were doomed to unhappiness. Rumors ran rampant through their church, “What had the Spaffords done that God could visit such misfortunes upon them?” Horatio left the Fullerton Presbyterian Church, which he had helped to build. In solidarity a group of Spafford’s friends also abandoned the Chicago church and together decided to seek solace and God’s guidance in the Holy City of Jerusalem. Delaying only until the birth of their daughter, Grace, in August 1881, the Spaffords set out for Jerusalem with a band of thirteen adults and three children.

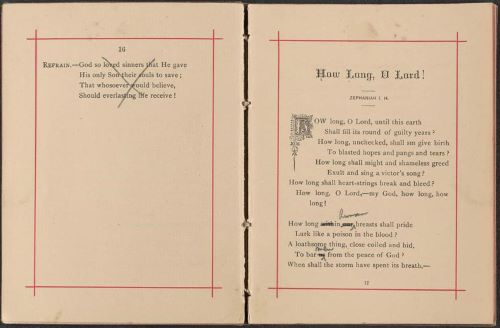

“How Long, O Lord!”

“How Long, O Lord!” is one of twenty poems by Horatio Spafford printed in a slim pamphlet entitled, Waiting for the Morning. These poems trace Spafford’s spiritual journey after the shipwreck, when he decided that material possessions and worldly success (“might and shameless greed”) were unimportant in the light of his loss. On the title page of this volume, Horatio is identified as the author of “Twenty Reasons for Believing the Coming of the Lord is Nigh,” a theme he continued to address in these poems.

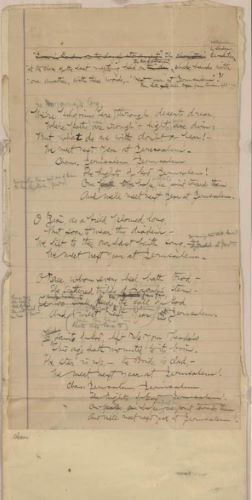

“Next Year in Jerusalem”

Horatio Spafford probably wrote this hymn in 1879. In it he explored the belief, held by some Christian sects, that the return of the Jewish people to Jerusalem was a sign of the imminent second coming of Jesus Christ. The corrections, most probably penciled in after he arrived in Jerusalem, give an insight into how Horatio’s supreme trust in God’s plan for him was reinforced by his experiences in the Holy Land. Notice the change from present to past in the first two lines and the addition of “join us herein.”

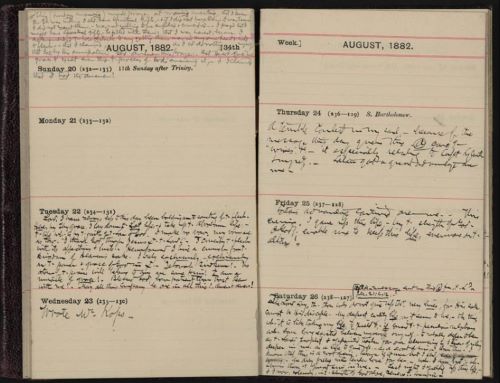

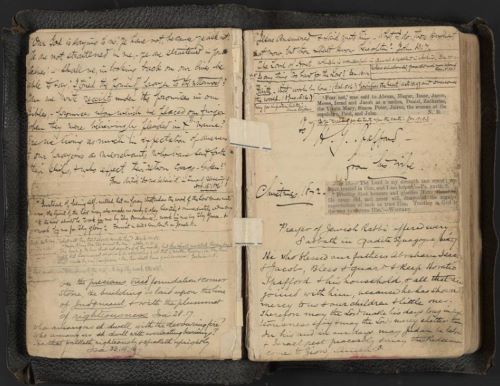

Horatio Spafford’s Diary, August 1882

Written almost a year after he left Chicago for Jerusalem, the two pages of this diary show Horatio dedicating himself to rely “exclusively on the power and grace of God in Christ.” It is an intimate glimpse into his spiritual quest. He writes: “Lord, I have always up to this day been holding on to something of the flesh. I crucify the flesh with its affections and lusts. Henceforward I live a eunuch for the Kingdom of Heaven’s sake. I rely exclusively, exclusively on the power and grace of God in [Christ]. I am a miracle of grace! Blessed God how patient thou hast been with me!”

Spiritual Struggle

In a letter sent from Jerusalem to relatives, Anna Spafford recalled the family’s spiritual struggles in the aftermath of their tragic loss and relocation to the Holy Land. She writes: “I wonder how long we shall hold this old house on the wall (pictured in photo). There is no place like it in all Jerusalem and here this work was started and held & all the battles fought over self & sin. Every stone speaks of victory and strength. Here Horatio lived and died & left us his strong spirit to copy.”

In the Holy Land

Overview

In a rented house in the Old City, the group quickly adapted to their new surroundings. Because they had no interest in proselytizing, they were warmly received by the local community, among whom they soon began philanthropic work. Called the “American Colony” by their neighbors, they sought to live a communal life on the model of the early Christian church. Horatio continued to search the Bible for guidance and for signs of the end of time when Jesus Christ would reappear in Jerusalem. Although the Colony was criticized and harassed by several of the American consuls in Jerusalem for their seemingly unorthodox religious life, the Colony survived and thrived as a religious community.

Letter to Piazza Smith

Horatio met the Scottish astronomer, Charles Piazza Smith, during a trip to London in 1870. Smith popularized the idea that each measurement of every passage, chamber, and gallery of the Great Pyramid in Giza, Egypt, indicated a historical event or prophecy and elucidated many mysteries referred to cryptically in the Bible. Horatio and Anna’s eldest daughter Bertha of their second set of children, believed that Smith instilled in Horatio an interest in the prophecies of the Old Testament that profoundly influenced him to turn to the Holy Land after he had suffered so many tragedies.

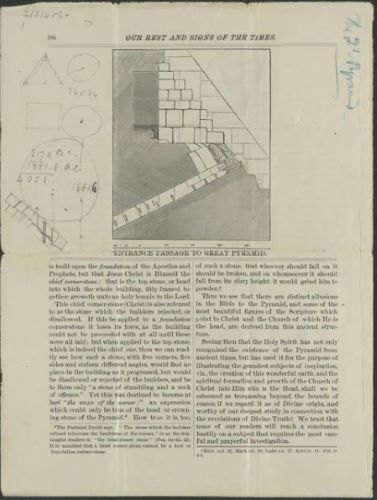

Our Rest and Signs of the Times

With a legal mind always searching for accuracy, Horatio subscribed to this popular journal, which contained in each issue “able articles on the Scientific and religious features of the Great Pyramid of Egypt…”

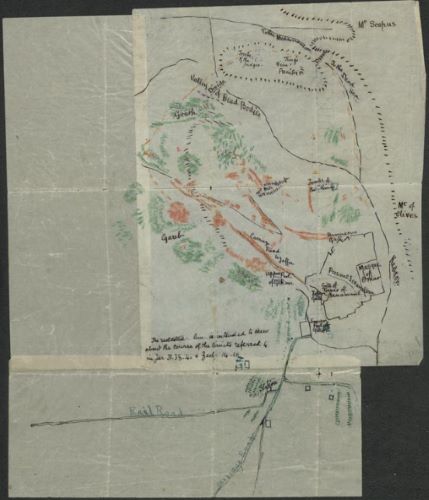

Prophetic Map of Jerusalem, ca. 1895

Searching the Bible, especially the Old Testament, for prophetic insight, members of the American Colony drew the boundaries of a future Messianic Jerusalem based on verses from the prophets Jeremiah and Zechariah:

‘The days are coming,’ declares the Lord, ‘when this city [Jerusalem] will be rebuilt for me from the Tower of Hananel to the Corner Gate. The measuring line will stretch from there straight to the hill of Gareb and then turn to Goah. The whole valley where the dead bodies and ashes are thrown… will be holy to the Lord…’

Jeremiah 31:38-40

Horatio’s Bible and the Prayer of the Gadites

In May 1882, the Spaffords met a group of impoverished Yemenite Jews recently arrived in Jerusalem. The Yemenites had come from their homes in southern Arabia because they believed that the time was right after thousands of years to return to the land that had been Israel. Impressed by their sincerity and claim to be descendants of Gad, a founder of one of the twelve tribes of Israel, the Spaffords housed and fed them until they could establish themselves in Jerusalem. In appreciation the Gadites bestowed a blessing on the Spaffords, which was recorded in Horatio’s Bible.

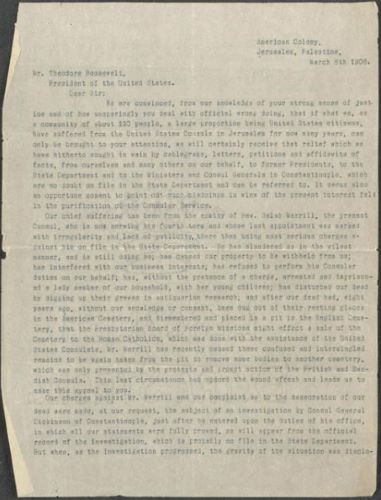

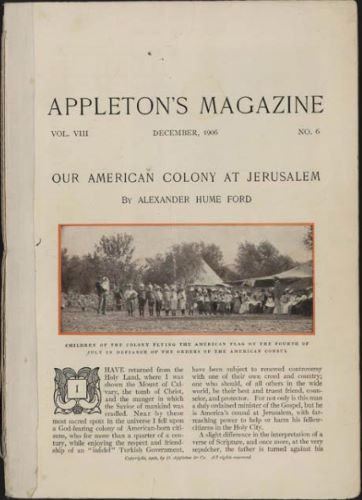

An Appeal to Theodore Roosevelt and Appleton’s Magazine

In March 1906, the American Colony petitioned President Roosevelt to address the malfeasance of the American consul of Jerusalem, Selah Merrill, who had also “slandered [the Colony] in the vilest manner.”

Over the years, the Colony had already lodged several formal complaints, in vain, about the actions of Merrill and another consul, Edwin Wallace. The publication of an article in the popular Appleton’s Magazine, which praised the Colony for its good works and Christian spirit and condemned the actions of the consuls, was the catalyst that finally led to the Colony’s total vindication.

The American Colony at Work

Overview

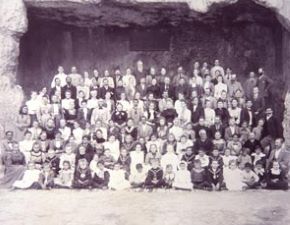

The community grew over the years. Visiting Chicago in 1894, Anna Spafford made contact with Olaf Henrik Larsson, the leader of the Swedish Evangelical Church. Inspired by Anna’s words and full of messianic fervor, the Swedes from Chicago decided to join Anna on her trip back to Jerusalem. Larsson also exhorted his relations and friends in Nas, Sweden, to go immediately to Jerusalem. As a result, thirty-eight adults and seventeen children sold all their possessions and set off for the Holy Land to join the Colony, arriving there in July 1896.

The Colony, now numbering 150, moved to the large house of a wealthy Arab landowner outside the city walls. The extensive land attached to the house was quickly put to use for the Colony’s support. Part of the building was used as a hostel for their frequent visitors from Europe and America. A small farm developed with cows and pigs, a butchery, a dairy, a bakery, a carpenter’s shop, and a smithy. The American Colony Store provided additional support through the sale of images, souvenirs, artifacts and archaeological objects worldwide.

The American Colony at Work

When the Swedes, who eventually joined the American Colony, left for Jerusalem, they brought their carpentry tools, hand looms, knitting machines and many farm implements with them.

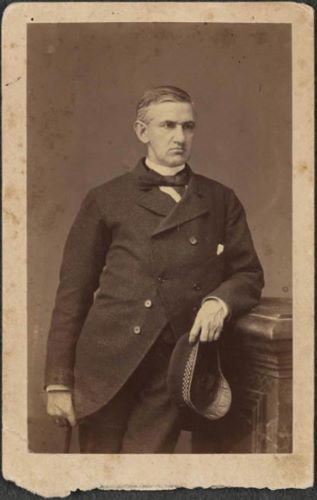

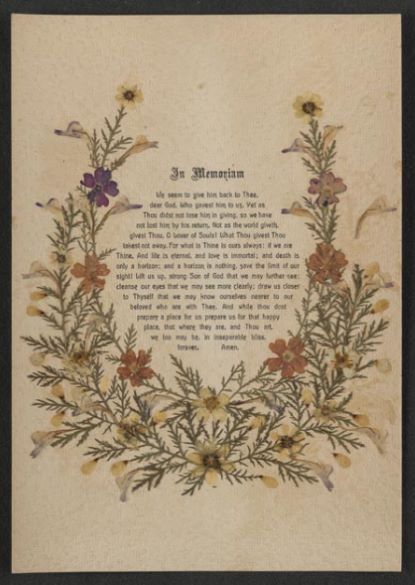

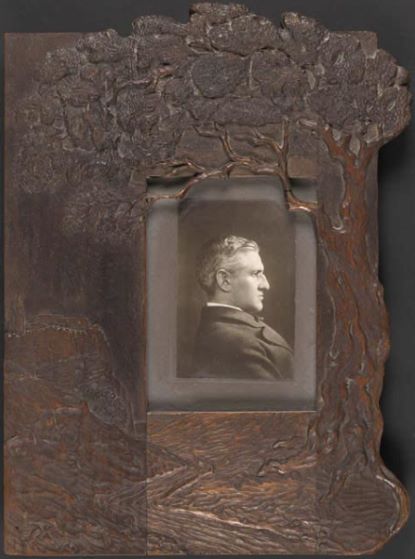

This photo of Horatio Spafford is encased in a frame crafted by the American Colony Carpentry Shop. Colony members also collected specimens of the flowers mentioned in the Bible that they pressed and pasted on cards and in albums and books to sell to tourists and pilgrims. Members fashioned this memoriam for Horatio when he died in 1888, at the age of sixty.

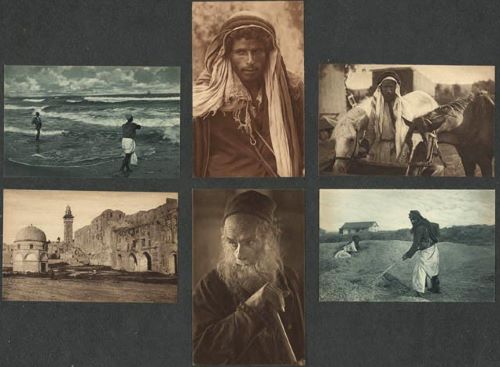

Photographic Department of the American Colony

In 1898, the Colony bought an old camera to document the visit of Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany to Jerusalem. From this humble beginning, the photographic studio became world famous for the thousands of images it produced of the Holy Land and the Middle East. Among the Colony members who worked in the studio were Lewis Larsson, Lars Lind, John Whiting, Frank Baldwin, and Eric Matson, whose photographic archive is housed in the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

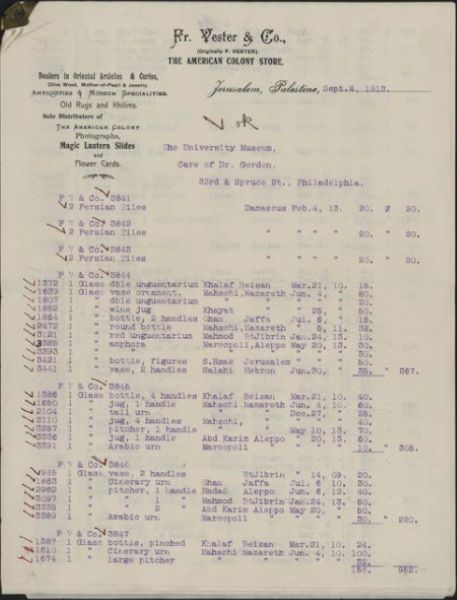

Inventory of Antiquities

In 1904 Bertha Spafford married Frederick Vester, whose father’s curio shop in Jerusalem had recently been bought by the American Colony. Renamed “Fr. Vester & Co., The American Colony Store,” the business greatly expanded its clientele and range of offerings to include photographs and collections of antiquities as shown in this inventory of ancient glass and pottery sold to the University of Pennsylvania Museum.

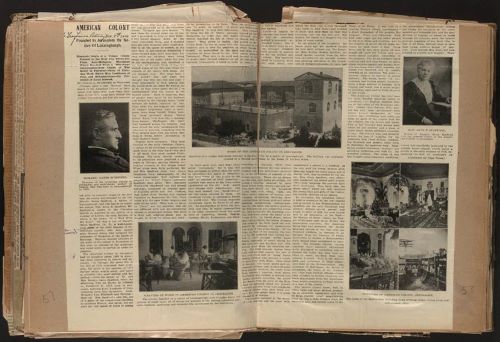

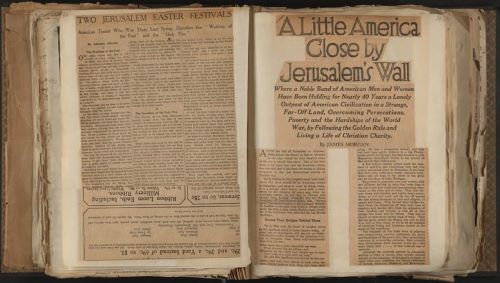

American Colony Scrapbook

In this scrapbook the Colony collected articles and stories that were published about its members between 1881 and 1930. In this article from the Troy Times (New York) dated December 9, 1916, the history of the Colony’s settlement in Jerusalem and the various activities of the Colony are described. As a new addition to the Library’s collections, this scrapbook, like many items in the American Colony-Vester Collection, will receive conservation attention to preserve it for posterity.

The Locust Plague

Overview

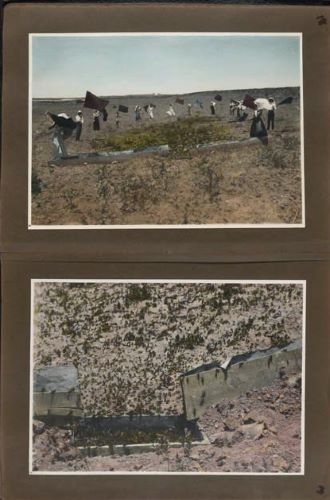

From March to October 1915, a plague of locusts stripped areas in and around Palestine of almost all vegetation. This invasion of biblical proportions seriously compromised the already depleted food supply of the region and sharpened the misery of all Jerusalemites. Djemal Pasha, Supreme Commander of Syria and Arabia, who mounted a campaign to limit the devastation, asked the American Colony photographers to document the progress of the locust hordes.

Locust Album

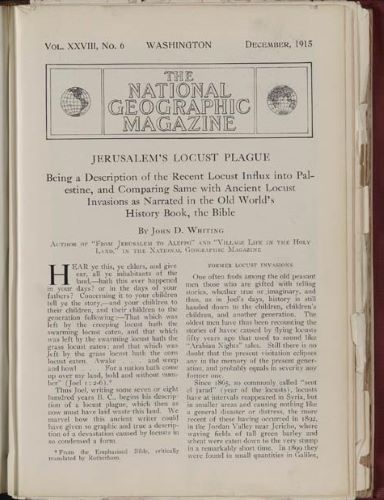

The Colony created the “locust album” that documented the course of the plague of 1915 at the request of Djemal Pasha. On these pages, a fig tree photographed just before and after the locusts attacked is graphic proof of the destruction wrought by the insect invasion. In his account of the devastation in The National Geographic, Colony member John Whiting wrote that the locusts were so voracious and numerous that they could swarm over an unguarded infant and devour its eyes within a few minutes.

Specimen of a Locust

This locust, from the 1915 invasion, is in its adult winged stage. It has hung on the wall of the American Colony Hotel for many years. After the locusts laid their eggs, Djemal Pasha ordered all adults and youth in and around Jerusalem to dig up half a kilo of locust eggs in order to contain the next onslaught. This proved an impossible task as the female locusts burrowed their eggs into the hard stony soil.

John Whiting Describes the Locust Invasion

Born in Jerusalem after his parents arrived with the Spaffords in 1881, John Whiting spoke fluent Arabic and was an expert on the topography, history, and local customs of the Holy Land. He served as American Vice-Consul of Jerusalem from 1908–1910 and from 1915–1917. The National Geographic published several of his articles on Palestine including his account of the locust plague of 1915. John Whiting married Grace, a daughter of Horatio and Anna Spafford.

Djemal Pasha at the American Colony

Two-year-old Louise Vester sits on the lap of Djemal Pasha and beside her mother Bertha and brother John. The cordial relationship that existed between Djemal Pasha, Supreme Commander of Syria and Arabia and military governor of Jerusalem, and the Colony facilitated its members’ relief work during World War I.

World War I

Overview

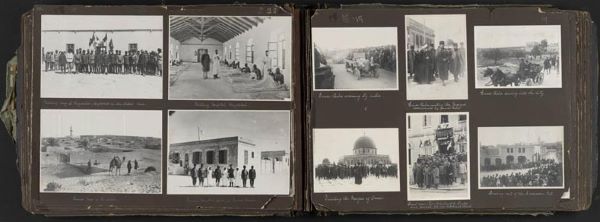

When the Ottoman Empire entered World War I as an ally of Germany in November 1914, Jerusalem and Palestine became a battleground between the Allied and the Central powers. The Allied forces from Egypt, under the leadership of the British, engaged the German, Austrian and Turkish forces in fierce battles for control of Palestine. During this time the American Colony assumed a more crucial role in supporting the local populace through the deprivations and hardships of the war. Because the Turkish military commanders governing Jerusalem trusted the Colony, they asked its photographers to record the course of the war in Palestine.

The Colony was permitted to continue its relief efforts even after the United States entered the war on the side of the Allies in the spring of 1917. As the German and Turkish armies retreated before the advancing Allied forces, the American Colony took charge of the overcrowded Turkish military hospitals, which were inundated by the wounded.

World War I Photographs

The American Colony photographers produced two albums documenting the war in Palestine. As this album demonstrates, Colony members photographed close to the front lines (left page) and recorded official occasions such as the visit of Enver Pasha, Turkish Minister of War, to Palestine and the Sinai Front in 1916 (right page). As a new addition to the Library’s collections, this photographic album, like many items in the American Colony-Vester Collection, will receive conservation attention to preserve it for posterity.

“A Little America Close by Jerusalem’s Wall”

This scrapbook is open to an article that appeared in the Minneapolis Sunday Tribune on July 4, 1920, which chronicles the history and survival of the American Colony. The author characterized the Colony as a “noble band of American men and women [who] have been holding for nearly 40 years a lonely outpost of American civilization in a strange far-off land, overcoming persecutions, poverty, and the hardship of the World War by following the Golden Rule in living a life of Christian charity.” As a new Library acquisition, this scrapbook, like many items in the American Colony-Vester Collection, will receive conservation attention to preserve it for posterity.

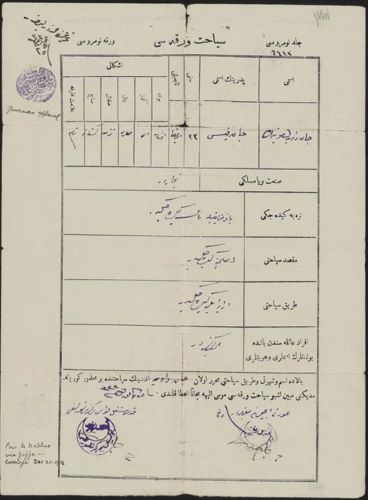

The Occupying Turkish Government

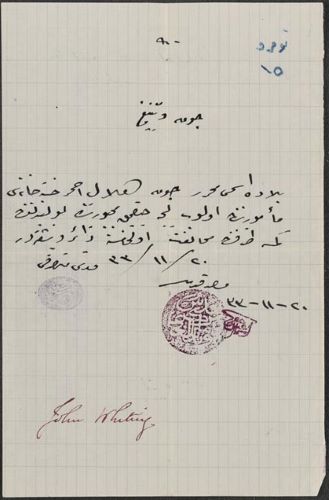

As the occupying force during World War I, the Turks imposed a strict system of wasikas, or travel permits, for movement within Palestine during the war. This travel permit gives a Colony member permission to travel.

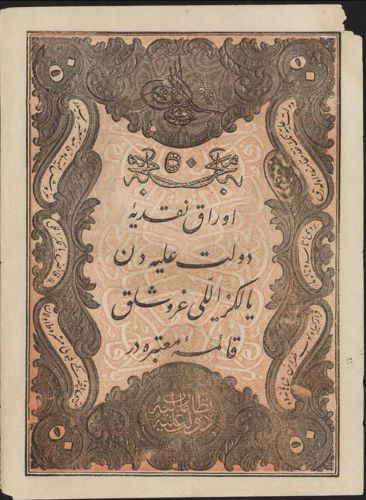

The paper currency, like the sample above, issued by the Turkish government during the war quickly became worthless. Gold coins were necessary to purchase goods or secure favors from government officials.

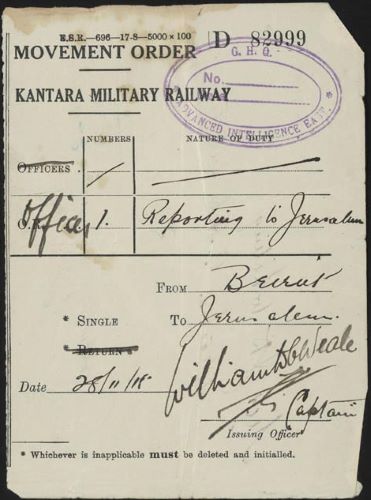

British Travel Pass

After they assumed control of Jerusalem on December 11, 1917, the British military command appointed John Whiting of the American Colony as Deputy Chief of Intelligence. This pass authorized him to travel from Nablus via Jaffa on December 25, 1916.

The American Colony Nurses

In April 1917 , the American Colony volunteered to administer six Turkish military hospitals in Jerusalem. This offer helped to save the Colony’s members from being deported after the United States joined the Allies.

Izzet Pasha, the last Turkish military governor of Jerusalem, provided the nursing corps with all necessary assistance, including night passes, such as this one issued to John Whiting (then serving as a Colony nurse), to move freely throughout the city.

Wartime Aid

Overview

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 brought great suffering to the country. All young men were conscripted into the army, while the older men were drafted into work brigades. Food supplies dwindled as the Allies sustained a blockade of the Palestinian coast, and the Turkish army confiscated provisions. Weakened by malnutrition, people died of typhus and other epidemics. As famine, disease, and death ravaged the people of Jerusalem, the Colony, struggling for their own survival, engaged in relief work. With money from friends in the United States, the American Colony ran a soup kitchen that fed thousands during these desperate times. When the British Allied commander, General Allenby, entered Jerusalem on December 11, 1917, the Colony offered their philanthropic services to the new rulers of Palestine and continued to serve their fellow Jerusalemites.

Relief Work

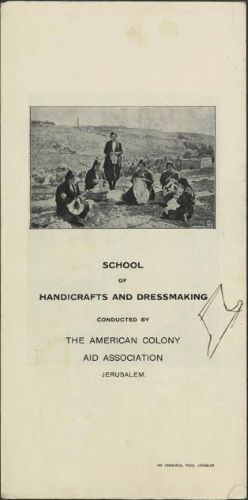

During the war the Colony opened an embroidery industry that sustained about 300 women whose husbands, fathers, and brothers were in the army or forced labor corps. When the food scarcities during the war became insurmountable, the Colony closed this workshop because the women became too hungry and emaciated to work.

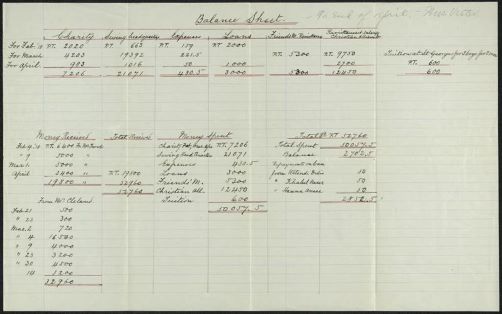

After the British conquered Jerusalem in December 1917, the Colony became the conduit of funds for organizations such as the Syrian and Palestine Relief Fund and the Christian Herald Relief Fund, which allowed them to open a new embroidery and dressmaking school. This account book and balance sheet records the Colony’s expenses, remittances, and other charitable allocations to the destitute living in Jerusalem during 1918.

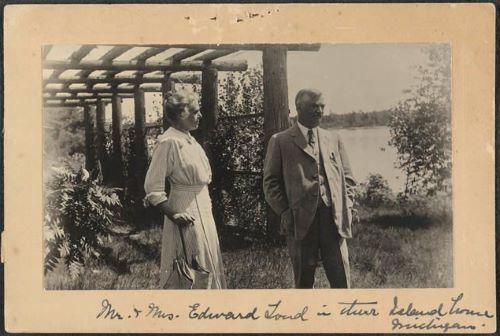

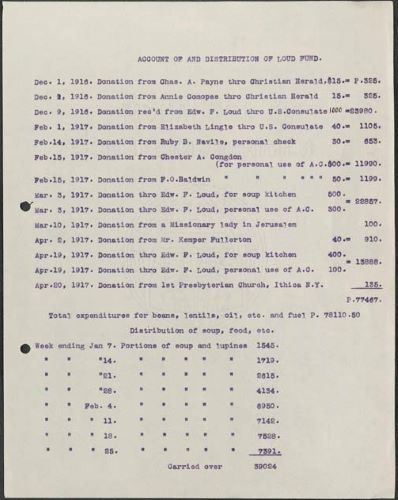

The Loud Soup Kitchen

In December 1915, Edward Loud of Oscoda, Michigan, offered to organize funds to send to the Colony for relief work. Loud had visited the Colony before the war, and, like many visitors and guests, he maintained close contact with members of the Colony when he returned home.

With the funds marshaled by Loud, the Colony created a soup kitchen that fed more than 1,100 people a day. Bertha Vester wrote to Loud that, “We make no distinction in nationality or creed, the only requirement being if they absolutely need the help. We have Syrians and Arabs… Latins and Greeks, and Armenians, Russians, Jews, and Protestants.”

Continuing Relief Work

Overview

The Colony also administered an orphanage to provide refuge for the many children torn from their parents during World War I. The charitable work begun by the Spaffords continues today in the original Colony house abutting the walls of the Old City of Jerusalem. The Spafford Children’s Center provides medical treatment and outreach programs for Arab children and their families in Jerusalem.

Inner tensions within the American Colony led to the final demise of this utopian Christian community in the 1950s. Since then the second home of the American Colony, outside the city’s walls, has functioned as a hotel—one of the most famous and beautiful in the Middle East—where members of all communities in Jerusalem can meet.

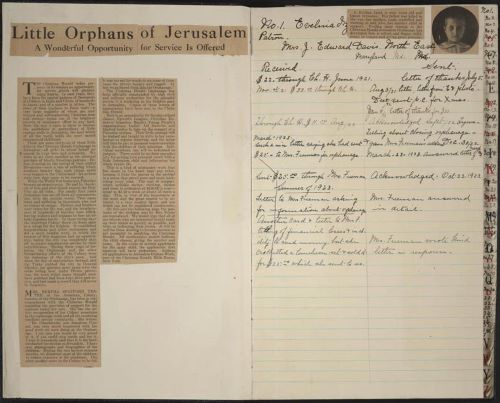

The Christian Herald Orphanage

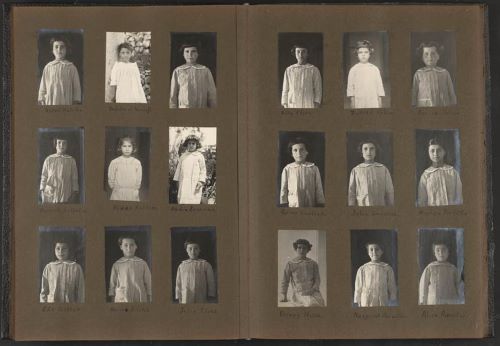

From 1918 to 1922 the American Colony ran an orphanage under the auspices of the newspaper, Christian Herald, to provide material and spiritual succor to Jerusalem’s orphans of war.

This register includes biographical details of children in the Christian Herald Orphanage and the photographic album documents the daily life of children at the orphanage and includes children’s portraits such as those displayed here.

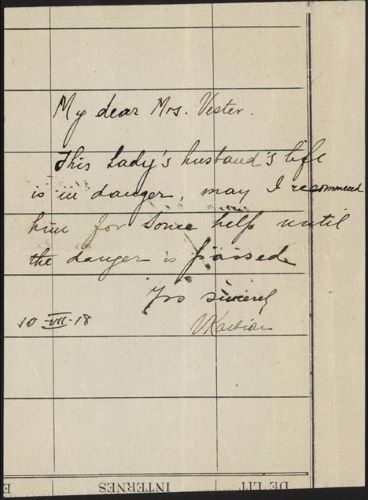

Appeals for Aid

These notes are two examples of urgent appeals sent to Bertha Vester in war-torn Jerusalem. Here two residential Jerusalem doctors (Dr. Haddad on July 20, 1921, and Dr. Kalbian in July 10, 1918, make a direct plea to Bertha for patients in dire need of assistance from the American Colony.

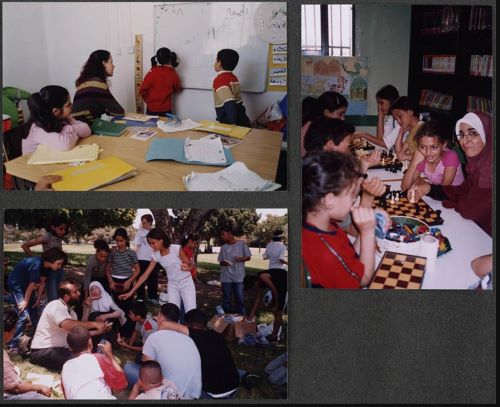

The Spafford Children’s Center

Created by Bertha Vester in 1925, to honor her mother Anna who died in 1923, the Spafford Children’s Center today cares for more than 30,000 children each year. The Center, located within the walls of Jerusalem’s Old City in the American Colony’s first house, provides for the physical and mental health needs of the disadvantaged children of Jerusalem and the West Bank.

The Center’s activities include preventive care programs, counseling for children and their families on social and psychological problems, a special education program, and a cultural department that organizes heritage outings and summer camps.

Originally published by the United States Library of Congress, January 12-April 2, 2005, to the public domain.