The idea of the “people” as a united force suffused the imagery of the New Deal era.

By Dr. Michael Kazin

Professor of History

Georgetown University

In 1941, director Frank Capra and scriptwriter Robert Riskin, a passionate New Dealer, created Meet John Doe, an allegory of a failed fascist takeover of the United States. The film concludes with perhaps the purest expression of populist defiance ever seen on screen. A group of “ordinary Americans”—members of the John Doe Clubs—has just convinced their hero, played by Gary Cooper, not to commit suicide. Their unofficial spokesman, a tough newspaper reporter, turns to the would-be Mussolini—a wealthy publisher named D. B. Norton—and declares: “There you are, Norton! The people! Try and lick that!”

Meet John Doe reflects a cultural shift that owes a good deal to FDR and the New Deal—and to the people and movements that thrived in their shadow during the 1930s and early 1940s. The idea that Americans constituted a united or nearly united “people” who came together across religious and ethnic boundaries, and that this people formed a bulwark of opposition to economic elites who threatened democracy, was essential to the building of the New Deal coalition.

Of course, there’s seldom, if ever, a clear cause-and-effect relationship between culture and politics. Cultures change more slowly and in different ways than do political parties and electoral majorities. And the conventional wisdom that groups that have “conservative values” tend to vote for conservative politicians has little basis in U.S. history. For example, it wasn’t until the 1980s that regular churchgoers began to vote more for Republican candidates than Democratic ones.

But there’s little doubt that the idea of the “people” as a united force—often beset by elite groups more powerful than themselves, and responding sometimes timidly, sometimes with righteous determination—suffused the imagery of the New Deal era.

Here are some examples of how “the people”were represented in this imagined New Deal community:

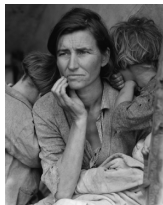

- the migrant mother by Dorothea Lange

- the CIO’s ordinary working man—Joe Worker

- Aaron Copland’s “Billy the Kid”—the eternal cowboy

- Dr. Seuss’s tough bald eagle—fighting fascism

- Paul Robeson, the great actor and singer

All these images and artistic works were created by liberals and radicals who, at the time at least, were strong supporters of the New Deal.We know how important the organized left was to the “folk revival”and to other projects dedicated to recovering the traditions of a diverse set of Americans. The broad coalition the Communist Party sponsored was called “the People’s Front,” and its aura stretched far beyond the rather small membership of the Party itself,which would have been positively minuscule if the CP hadn’t tacitly endorsed the New Deal from 1935 until the Hitler-Stalin pact in 1939.

Much of what we think of as New Deal culture was actually created by men and women who considered themselves part of the People’s Front. From the mid-30s on, few writers, artists, and folklorists thought they had to choose between their work in a cultural sphere shaped and dominated by radicals and their support for liberal Democrats in both the nation and their individual states.For many radicals, FDR was as much a hero as Earl Browder or Joe Stalin. All seemed to be on the same side in the epic battle against fascism and for democracy.

The culture of the People’s Front was one of the more significant subcultures in U.S. history.It helped unleash the creativity of men and women from immigrant backgrounds and minority races who wanted to claim America—its culture, its history, its tremendous economic opportunities—for themselves. This included novelists like Richard Wright, Tillie Olsen, Henry Roth, Pietro di Donato, and Thomas Bell—none of whom was a white Protestant.

Popular Front culture was varied, rambunctious, and full of confidence. It included songs like “Ballad for Americans,” written by Earl Robinson, a member of the Communist Party, and sung by Paul Robeson on a national radio broadcast in 1939.

A chorus asks Robeson, “Say, will you please tell us who you are?” And he answers, in part:

Well, I’m an

Engineer, musician, street cleaner, carpenter, teacher,

How about a farmer? Also. Office clerk? Yes sir!

That’s right. Certainly!

Factory worker? You said it. Yes ma’am.

Absotively! Posolutely!

Truck driver? Definitely!Miner, seamstress, ditchdigger, all of them.

I am the “etceteras” and the “and so forths” that do the work.

Now hold on here, what are you trying to give us?

Are you an American?

Am I an American?

I’m just an Irish, Jewish, Italian,

French and English, Spanish, Russian, Chinese, Polish,

Scotch, Hungarian, Swedish, Finnish, Greek and Turk and Czech . . .

It included labor-oriented musicals like The Cradle Will Rock and Pins and Needles, as well as dramas produced by Harold Clurman’s Group Theater and Orson Welles’ Mercury Theater. Welles’ great film Citizen Kane was inspired by the battles of leftists and liberals with William Randolph Hearst, the powerful publisher who was a vigorous foe of both FDR as well as socialism and communism.

Meet John Doe itself shows the influence of the pro-Roosevelt left’s definition of who were the enemies of “the people.” Riskin’s script focuses on an incipient American fascist movement, led by D. B. Norton, a vicious newspaper tycoon. The negative view of corporate America, particularly the press, echoed that of FDR as well as the reigning Marxist view of fascism as a conspiracy by big business.

But “the people” did not just resonate for the secular left during the 1930s.At the end of Meet John Doe, Barbara Stanwyck’s character, Ann Mitchell, tells John that he doesn’t have to die for the people because“the first John Doe” “already died for that”ideal—and “he’s kept” it “alive for nearly 2000 years.” And, the ending of the film takes place at midnight on Christmas Eve.

Religious populists hostile to the New Deal also claimed to represent “the people.” Gerald L. K. Smith, national organizer for Huey Long’s “Share the Wealth”campaign, declared that the only people who sincerely wanted to carry out a massive redistribution of resources were those true Americans who believed in “Santa Claus,Christmas trees, the Easter bunny, [and] the Holy Bible.” Father Charles Coughlin attracted a huge radio audience with attacks on “wicked men who . . . concentrated wealth into the hands of a few”—ungodly men who violated the truth “that all this world’s wealth of field and forest, of mine and river has been bestowed upon us by a kind Father” who wanted it enjoyed in roughly equal shares. Coughlin soon turned against the New Deal in 1934, claiming it was controlled by Jews and Communists. Like other conservatives at the time, he was quite radical in his fears.

Meanwhile, radicals in the People’s Front sounded quite conservative as they identified themselves comfortably with some of the iconic figures and moments in American history.Communist Party bookstores and schools were often named after Thomas Jefferson. In 1937, the Young Communist League (YCL) chided the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) for neglecting to celebrate the anniversary of Paul Revere’s ride. They marched up Broadway in New York City with a sign that read, “The DAR Forgets but the YCL remembers.”

But New Deal image-makers managed to dominate both the populist left and right. They coopted the left, since most of the same “people” whom radicals wanted to reach were already strong supporters of FDR. And they marginalized the right by initiating what historian Leo Ribuffo has called “a brown scare”—identifying Smith and Coughlin and Huey Long as incipient fascists, foes of democracy occupying a “lunatic fringe.”[1]

New Dealers appeared not so much to be fighting against ethnic and racial discrimination as to have pushed it to the margins of public discourse or, better, having transcended it altogether.There were good political reasons for this avoidance. FDR needed the strong support of white Southerners, and so he famously refused to endorse efforts to pass a federal anti-lynching bill in Congress. And Roosevelt himself never quite transcended prejudices he had imbibed as a privileged young man in rural New York state. In 1942, he told New Deal economist Leo T. Crowley,an Irish-Catholic, “Leo, you know this is a Protestant country, and the Catholics and Jews are here under sufferance. It is up to you to go along with anything I want.”

But anyone—right or left—who wanted to gain influence among discontented Americans had to cope with FDR’s mighty rhetorical powers. As William Allen White, the famous journalist who was a leading progressive Republican, commented in 1934, “He [FDR] has been all but crowned by the people.”

Roosevelt began his presidency with words that both comforted and energized Americans—even if they had a great deal more to fear than simply “fear itself.” Throughout his 12 years in office, FDR effectively communicated a fighting sympathy for their problems. He always seemed able to defang his opponents with a nonchalant aside or an everyday metaphor—like the deadpan 1944 story of his little dog Fala’s ire at Republican attacks or his 1941 equation of Lend-Lease to loaning a garden hose to a neighbor whose house was on fire.

He also had a knack for reassuring audiences who were wary of greater federal power that both the government and the future were on their side. In 1936, FDR visited a throng of North Dakota farmers afraid the government was about to move them off their drought-ravaged lands. “I have a hunch that you people have your chins up,” he told them, “that you are not looking forward to the day when the country would be depopulated . . . I say you are not licked.” FDR’s open and generous manner, his sure grasp of the civil religion, and his use of populist phrases like “economic royalist” and “the forgotten man” framed the rhetorical limits for most politicians and movement activists.

Roosevelt was not just fluent in the idioms of the civil religion; he often spoke in the idioms of Christianity—more so than any prominent liberal since his death. FDR sprinkled references to the Bible and Pilgrim’s Progress into many of his speeches. “The money changers have fled from their high seats in the temple of our civilization,” he announced at his first inaugural. “We may now restore that temple to the ancient truths . . . social values more noble than mere monetary profit.” “WE CANNOT READ the history of our rise . . . as a nation,without reckoning with the place the Bible has occupied in shaping the Republic,” he said in 1935.Accepting the Democratic nomination in 1940, he declared, referring to fascism, “WE FACE ONE of the great choices of history—religion against godlessness.”

Most Americans welcomed such language as displays of confidence—both self-confidence in his own decisions and confidence in the future of the nation. Eleanor Roosevelt’s frequent trips to show her solidarity with working people and the destitute closed the deal.

The New Deal did scare a lot of people. A majority of Americans often disagreed with a given FDR policy, and many were troubled by the growth of state power the New Deal represented. In the early summer of 1936—the year FDR won re-election in a landslide—the Gallup Poll reported that 45 percent of Americans agreed with the statement that “the acts and policies of the Roosevelt administration may lead to a dictatorship.”

But while that might occur in the future, in the present, most people were hungry for caring,protective leadership, and they trusted the Roosevelts’ concern for their plight. FDR’s most skillful demonstration of this kind of leadership was in his Fireside Chats, those seemingly informal but closely scripted radio broadcasts. The Chats gained huge audiences, larger than those for any individual radio broadcasts at the time. For example, the two fireside chats in the months following the attack on Pearl Harbor were heard or read by 80 percent of all adult Americans. FDR was literally speaking to all, or nearly all of “the people.” In the middle of one Chat in 1933, he invited the audience to “tell me your troubles.” Over the next week, the White House mail office received 450,000 letters, postcards, and telegrams.

With such means, FDR and his fellow New Dealers set the terms of political debate for 12 long years. No group could blaze a more radical path—drawing strict class lines, endorsing either communist or fascist aims, or flagrantly appealing to racism or anti-Semitism—without suffering a sharp and permanent decline in popular support.

Of course, the image of a united “people” was always a myth. The Depression had not quite healed the traumas of what historian John Higham called “the tribal Twenties”: harshly restrictive immigration laws, the bitter clash over the passage and enforcement of prohibition, the clash over the KKK’s role in public life. But in the 1930s, most Americans wanted to believe that those wounds had largely closed. They wanted to believe there was unity in suffering and, for some,resistance to greedy economic elites.

In fact, the old “Nordic” supremacy lived on, in imagery if not in New Deal rhetoric. As many scholars have pointed out, the dominant images of “the people” in the 1930s were usually white and implicitly Western or Northern European. Think of the migrant woman and the CIO’s Joe Worker. Americans with black or swarthy skin or kinky hair were largely ineligible for such symbolic spots. Everybody in the group of John Doe Club members at the end of Capra’s film is white, nicely dressed, and speaks English without the trace of an accent. Their Christianity is assumed.

But such ethnic and racial exclusions were hardly new in American cultural and political iconography. During the New Deal years, the ends for which these images were being used were new.And that mattered a great deal.

The supposed unity of “the people” helped maintain support for the U.S. effort in World War II. The Second World War was far more popular among Americans than was World War I.And this was not only because of the attack on Pearl Harbor. FDR and his spokesmen and allies were able to attack the enemy as a group that was trying to divide Americans by race and religion. In PM,the pro–New Deal daily, Dr. Seuss depicted foes of FDR such as Charles Lindbergh and Gov. Eugene Talmadge of Georgia as unpatriotic bigots.

Many of the features of New Deal/Popular Front culture survived, even flourished into Cold War America, even as liberals and radicals were forced on the defensive politically.This was true for Aaron Copland’s music, which came to seem as patriotic as “God Bless America.” It was also true for folk music, from the Weavers to the early songs of BobDylan, and for the ethnic fiction that survived in novels like Howard Fast’s The Immigrants and was transmogrified into such 1950s TV sitcoms as The Honeymooners and The Goldbergs (based on the popular radio show of the 1930s and 40s), and in such movies as On the Waterfront and The Godfather. It was also true for one of the most significant events along the hard road to a racially integrated America—Jackie Robinson’s breaking the color line in major league baseball in 1947. For years, black newspapers, PM, and The Daily Worker, had led the attack on the Jim Crow order in the nation’s most popular sport. On opening day of the 1945 baseball season,some communists even picketed Yankee Stadium. What’s more, Dr. Seuss kept writing and illustrating children’s books with thesame left-populist message he had adopted in the 1930s—from Yertle the Turtle to Horton Hears a Who to The Lorax to the Butter Battle Book.

The creativity and flexibility of New Deal/Popular Front culture enabled its practitioners to tap into certain veins of dissent and resistance that run deep in American history: its anti-authoritarian spirit, its celebration of hard work, and its romance with the land and with regional vernaculars in language and performance. But this flexibility also meant that cultural forms that first blossomed on the left could also work for those who grew hostile to the political causes that helped to spawn them.One of the best examples is On the Waterfront, written to justify Elia Kazan’s naming of names to a congressional committee.In other words, “Try and lick that!” could have promiscuous applications.

The aggrieved populism captured by the New Deal had always been a malleable concept. Until its conclusion, Meet John Doe is not a romantic statement about the people’s ability to resist tyrants and organize themselves to build a better nation. Gary Cooper’s character—Long John Willoughby—is an amoral drifter who agrees to play the central role in a publicity stunt created by Stanwyck’s character to save her newspaper job. D. B. Norton organizes the John Doe clubs as an ostensibly “apolitical” front for his own independent,right-wing presidential campaign. When John realizes he’s being manipulated, he decides to commit suicide to show he was sincere about the purpose of the Clubs, after Norton has exposed him as a fraud. So one message of the film is that “the people” can be easily fooled—and used. Or to put it less cynically, definitions of the “elite” and “the people” are not tethered for long to the benefit of any one political force or cultural movement.

After World War II, conservatives like Sen.Joseph McCarthy reaped great benefits when the popular image of elites who despised the values of ordinary Americans switched from figures like D.B.Norton, Talmadge, and Hitler to that of Stalin, Alger Hiss, and the Hollywood Ten. “The people” now seemed morally opposed to any American who had ever said a good word for such evil men or had been affiliated, however briefly,with a movement that praised them in word and deed. Frank Capra himself switched from being a mild supporter of the New Deal to being a conservative anti-Communist.

In 1980, Ronald Reagan—the conservatives’ Roosevelt—rose to power partly by adapting the New Deal praise for “the people” that he had once deployed as a liberal and a union leader. And Reagan managed this feat with an avuncular tone and a common touch that was unmatched by any politician since FDR.

In his first inaugural address, Reagan called up a rhapsodic roster of working Americans that echoed Paul Robeson’s list from 40 years before—one that any New Deal spokesman would have happy to repeat: “men and women who raise our food, patrol our streets, man our mines and factories, teach our children, keep our homes, and heal us when we’re sick . . . this breed called Americans.” In a Labor Day address Reagan gave in 1985, he promoted an income tax plan that he said “the special interests” opposed: “Our fair tax program,” he declared, “is a good deal for the American people and a big step toward economic power for people who’ve been denied power for generations.” Actually, the proposal he was advocating cut rates dramatically for the wealthiest five percent of Americans while raising, slightly, the taxes most families had to pay.

So conservatives rose to dominate the nation’s politics in the late 20th century with language that often echoed that which FDR and his allies had used half-a-century earlier to put liberalism in command. I suppose the lesson of is that one should never underestimate the significance of irony as a force in history. New Deal culture was powerful enough to serve many masters.

Originally published by the Federal History Journal, 2009, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.