Portrait of Thomas Jefferson, by Rembrandt Peale, 1800, oil on canvas / White House

Dr. Freeman lays out the logic of American resistance to British imperial policy during the 1770s. Prime Minister Lord North imposed the Intolerable Acts on Massachusetts to punish the radicals for the Boston Tea Party, and hoped that the act would divide the colonies. Instead, the colonies rallied around Massachusetts because they were worried that the Intolerable Acts set a new threatening precedent in the imperial relationship. In response to this seeming threat, the colonists formed the First Continental Congress in 1774 to determine a joint course of action. The meeting of the First Continental Congress is important for four reasons: it forced the colonists to clarify and define their grievances with Britain; it helped to form ties between the colonies; it served as a training ground for young colonial politicians; and in British eyes, it symbolized a step towards rebellion. The lecture concludes with a look at the importance of historical lessons for the colonists, and how these lessons helped form a “logic of resistance” against the new measures that Parliament was imposing upon the colonies.

Lecture by Dr. Joanne Freeman / 02.04.2010

Professor of History and American Studies

Yale University

Introduction: The Logic of Resistance

Cartoon depicting Lord North, with the Boston Port Bill extending from a pocket, forcing tea (representing the Intolerable Acts) down the throat of a female figure representing the American colonies. / Library of Congress

Today we are going to make our way to the logic of resistance, and what I mean by that is the mindset that contributed to some of the broad conclusions that the colonists were drawing as events were unfolding in the 1770s. But to get to the logic of resistance we first have to lay out another event that contributed to the building of that logic. And I mentioned it right at the end of the last lecture — and that event is a series of acts that were passed by Parliament in 1774, and Americans ended up calling them the Intolerable Acts, which will be an easy way to remember what they are, the Intolerable Acts. They also were called the Coercive Acts but intolerable would have been what Americans — what the colonists would have considered them.

They were a response to the destruction of the tea in Boston Harbor, which sort of dumbfounded Lord North who had assumed that his Tea Act, passed in 1773, was going to be seen as maybe a relief by the colonies; that North had been trying to save the East India Company from going under; he had reduced duties on East India tea so that people would be buying that tea, passed the act, thought this would be seen potentially as a good thing — only to find that the colonists saw it as an attempt of the British government to have a monopoly over what the colonists had assumed was free trade. And that’s where you get the broadsides that I was just talking about, telling people not to buy or sell East India tea and to act now, defend your liberties. And then eventually you end up with the destruction of tea in Boston Harbor. And as I mentioned in the last lecture, “Boston Tea Party” is actually later in the nineteenth century. They didn’t call it this at the time. They probably called it “the destruction of the tea,” but it was not a party [laughs] at the time. That was later they decided it was a tea party.

North’s Intolerable Acts and Colonial Solidarity

View of Boston Harbor, by Franz Xaver Habermann, 1770 / Boston Public Library

So now clearly, having had that happen, North felt that something really needed to be done about the colonies, or obedience to British law and order, in his mind, would collapse in the colonies. As he put it, and I think I quoted this right at the end of the lecture, that if they didn’t risk something, all is over. A dramatic statement. Thus you get the Intolerable Acts, which are passed in the spring of 1774, and although there were some in Parliament who protested against them, still they passed with a great majority. Those who did protest against them argued that the American colonists deserved the same rights as any other British subjects and, as I describe the acts to you, you will understand why these friends to America were making this argument. You’ll hear the details and see that their argument certainly made sense at that moment.

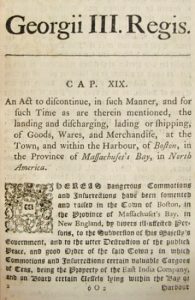

So there were four acts that get lumped together as the Intolerable Acts. The first one: the Boston Port Act, which closed the port of Boston to all shipping until the colonists paid for the tea that they had destroyed, and I suppose also hopefully showed some degree of remorse for having destroyed all that tea. Now clearly that’s a pretty extreme measure, right? — closing the port of Boston, period. And North assumed that it would pretty much crush the opposition in Boston and that other colonies would scramble for Boston’s lost trade and ignore what was happening in Boston. And we’ll see this again and again — that there is sort of a fundamental misunderstanding about when and what ends up seeming like a joint threat to the colonists so that they act together versus what doesn’t inspire them to act together. So here we see Lord North assuming that if Boston loses trade the other colonies will just sort of gobble it up and the Boston radicals will sort of get silenced and that’ll be the end of this matter, but he misjudges colonial sentiment, in this case really underestimating the sense of unity that arises from something that ends up being seen as a joint threat.

So the British government ends up being rather stunned when the other colonies not only don’t ignore Boston but instead they actually support it in its time of need. So other colonies responded to the Boston Port Act and some of these other acts by sending goods. So Connecticut sent sheep, Charleston sent rice, Philadelphia sent flour. So the other colonies basically stepped up and did something in Boston’s time of need and a lot of colonies made June 1, which is the day that that act was supposed to take effect, a day of fasting and prayer.

Now clearly some of this was because people felt sympathy for what was happening in Boston; they saw and felt for Boston and its plight. But equally if not more important, people in other colonies assumed if it could happen in Boston, it could happen anywhere. So in a lot of ways, Boston’s cause was their cause. It wasn’t something happening far away. It was something that there was no reason why they couldn’t see it couldn’t happen anywhere else where the British government happened to be angry at something that happened.

So in essence Lord North’s actions did the precise opposite of what they were meant to do, because they really ultimately brought the colonies closer together in a shared sense of crisis. As George Washington put it in his typical kind of meandering, indirect way — Washington is not always the best wordsmith. Washington had very good people writing for him. He had good speech makers, that Washington, but he tends to write in kind of a meandering style, and this will be kind of a typical Washingtonian statement full of parenthesis and weird clauses, but his heart’s in the right place. Okay. So Washington says, “The ministry,” the British ministry, “may rely on it, the Americans will never be tax’d without their own consent[,] that the cause of Boston[,] the despotick Measures in respect to it I mean[,] now is and ever will be considerd as the cause of America (not that we approve their conduct in destroying the Tea),” this is all one sentence [laughs] — and that “we shall not suffer ourselves to be sacrificed by piece meals though god only knows what is to become of us.” It’s sort of a Washingtonian sentence but still, he’s making his point really clearly.

Boston Port Act of 1774 from Parliament and George III / Library of Congress

So the Boston Port Act, number one of the Intolerable Acts. The other three — still pretty largely focused on Massachusetts — included a Quartering Act, and the Quartering Act legalized the quartering of British troops not only in empty buildings or taverns but also in private homes; the Administration of Justice Act, which was an attempt to protect people who were trying to suppress revolts in the colonies. So the Administration of Justice Act said that if a fair trial for a British soldier or official couldn’t be had in Massachusetts, the trial could be transferred to another colony or to England. And in Massachusetts, the land of propaganda, this became known as the Murder Act. [laughs] Just in case you want to wonder what people are thinking about it. And as someone at the time put it, “Every villain who ravishes our wives [or] deflowers our daughters, can evade punishment by being tried in Britain, where no evidence can pursue him.” Okay. We’re not really talking so much about ravishing and deflowering. We’re really talking about [laughs] taxes and such — but still, you could understand the logic why people feel that — again — some fundamental liberties are being violated here.

And then finally the last of these acts is the Massachusetts Government Act, and in a lot of ways that ended up being the most controversial act of all, because it basically imposed a new charter on the colony of Massachusetts. From now on, the governor, who was appointed by the King, could appoint his own council rather than having the council be elected by the colonial assembly; the council could no longer veto the governor’s decisions; all town meetings besides the one annual meeting for electing officers now needed to be approved by the governor, and if the governor wanted he could simply forbid town meetings; and any additional meeting besides the one in which officers were chosen — that meeting needed to post an agenda in advance and stick to the agenda; and the governor also now could appoint or remove sheriffs, judges, attorney generals, marshals. So basically the governor is a royal official and the governor is now in Massachusetts being given a lot of power.

So I’ll repeat the four Intolerable Acts: the Boston Port Act, the Quartering Act, the Administration of Justice Act, and the Massachusetts Government Act. So having described those acts, you can see why there would have been some in Parliament who were sympathetic to what was going on in the colonies who would have protested that these acts were depriving colonists of some pretty basic British constitutional rights, but these protestors were in the minority.

Now on top of these acts the King sent a new governor to Massachusetts, Massachusetts General Thomas Gage, commander of the British forces in North America. Okay. So a military commander was sent to be the new governor — again, a pretty dramatic statement. So now in addition to all of those acts, you have the looming threat certainly to the colonies or the colonists in Massachusetts of a standing army as a source of tyranny staring them in the face. So certainly people in Massachusetts at this moment would have been justified in feeling as though they were under military occupation.

The First Continental Congress

Carpenter’s Hall in Philadelphia, meeting place of the First Continental Congress / Wikimedia Commons

Now we may look at these pretty drastic measures and assume that reconciliation is pretty impossible at this point. And I know a few of you came up to me after class on Tuesday and actually were already leaning in that direction — like, ‘when are we getting the independence, because how in the world can they get out of this?’ Right? [laughs] ‘It’s looking pretty bad. Look at these really extreme measures.’ Certainly it looks as though rebellion is on the horizon.

But independence is not the natural choice. That’s a really, really radical move that is not at this moment on the horizon. These are really — And I’m going to talk more about this in this lecture a little further on. These are British subjects trying to demand the rights of British subjects. That’s the logic that’s at play here. They’re not thinking independence. They’re thinking that they need to find a way to get the British imperial system to work in a way that they see as being right. They’re not trying to break away. They’re hoping that there’s a way to fix things, and that they will get what they feel they deserve as British subjects.

So in 1774, it was in the hope of maybe figuring out some way to settle things, some way to compromise, some way to come to some sort of a solution that the Massachusetts legislature sent a circular letter to the other colonies suggesting that it might be smart to have a joint congress from all the colonies to discuss their problems and to figure out a course of action that made sense. So what came to be known as the First Continental Congress, right? — the congress of the continent — met in Philadelphia at the end of August in 1774. Most of the delegates to that Congress already had some political experience in their separate colonies. None of them were absolute uncompromising radicals who wanted to rip everything apart. It was not a sort of dire radical body, and I’ll be talking a little bit more about the First Continental Congress in a lecture to come but for now, I’ll just state — I guess — four significant things about the meeting of the Congress.

Okay. First, and it’s actually kind of practical, the meeting of the First Continental Congress forced the colonists to make their beliefs clear to themselves — as people from a variety of different colonies — and to Great Britain, and to explain the motives behind their actions as they debated and drafted petitions and resolves and declarations. The delegates were clarifying and defining their thoughts, and they were doing it in a room full of delegates from other colonies that people didn’t necessarily know that well. So it was actually just in and of itself by collecting all these people together in a room and forcing them to sort of think things through, talk things through and come up with some kind of a resolution they were actually hashing out their problems on a broad level in a way that they had not done before.

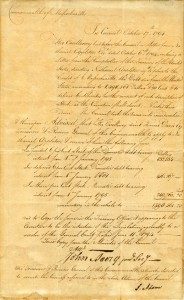

John Adams diary entry from December 18, 1765 / Library of Congress

Second, a Continental Congress forced people from very separate colonies — in a way, really sort of separate nation-states — to meet one another and stay with one another for an extended period of time. And for a lot of the people that were there, this was really their first extended period spent with people from faraway colonies. So not only did this contribute to a sense of colonial unity, but it actually on a really practical level, it gave people a chance to see how other colonies ran their colonial governments. And John Adams actually — He writes a great diary at the time, and in his diary he writes about how when he’s in this congress he spent a lot of time grilling people from other colonies, asking questions about their charters, their laws, the logic behind them. He really wanted to understand how other colonies worked.

And it’s interesting because in his letters — I think also in his diary but in his letters for sure — Adams refers to himself and his position in the Continental Congress as “our embassy,” right? And by “our embassy,” what he means is, he sees himself as a kind of diplomat representing Massachusetts in a sort of — today you might say — international body, but he sees the Continental Congress as a sort of grouping of representatives of other provinces or other countries or nations, and he’s a delegate from our embassy of Massachusetts. So in a way we put a lot of baggage into the word “congress” as though, ‘oh, it’s a bunch of Americans joined in a congress,’ but it’s not a Congress in our modern sense of the word. It really is in their mind a sort of delegation of people representing different nation-states, which is why it was so interesting for them to collect together and get to exchange thoughts.

And then third, to John Adams and some others, the fact that now this Congress existed seemed to be, or at least to hold the potential for being, some kind of a training ground for American statesmen. And Adams put it at the time, said that the Congress was quote, “to be a School of Political Prophets I suppose — a Nursery of American Statesmen. May it thrive, and prosper and flourish and from this Fountain may there issue Streams, which shall gladden all the Cities and Towns in North America, forever.” John Adams always has a way of saying the big, broad quotable thing, which is why I keep coming back to him. Hello. I will provide you the historian with the big, broad, wonderful quote about the Continental Congress. Thank you, John Adams. “I am for making. . . [the congress] annual, and for Sending an entire new set [of delegates] every Year, that all the principal Genius’s may go to the University in Rotation — that We may have Politicians in Plenty. . . Our Policy must be to improve every opportunity and Means for forming our People, and preparing Leaders for them in the grand March of Politicks.” So he’s drawing a lot of big hopes for the future from the meeting of this Congress, but certainly he’s thinking — the fact that it exists and that these people will be meeting and talking in this way on this level will be in and of itself a sort of educational colonial experience.

And then finally a fourth significant aspect of the meeting of this Congress was that at least to some back in England the Continental Congress symbolized a move towards rebellion. And indeed more about this to come, but in February of 1775, Lord North passed a resolution in Parliament declaring that Massachusetts was in a state of rebellion. And part of the reason why it’s Massachusetts that he’s focusing on is because really still in Parliament, they are assuming that Massachusetts is the ringleader of all the trouble; the real reason for the Congress is Massachusetts; Massachusetts is the problem; Massachusetts is moving towards rebellion; and to some people back in England looking on, this Continental Congress looks treasonable.

So you can see how things are evolving here. You can see how mutual misunderstandings are growing. Colonists and the British administration are grappling with the real meaning of British sovereignty in the colonies. The British government isn’t really clear on some of the logic of colonial thinking on such matters. Colonists see an ongoing attempt to violate their fundamental rights as British subjects as they have come to understand them, which brings us to the perfect segue into a discussion of the logic of colonial resistance, the logic driving the colonial mindset during the passage of the 1770s.

Jefferson’s Dinner Party and the Influence of Enlightenment Thought on the Colonists

Dinner Party Compromise of 1790 / Library of Congress

And what I’m going to do now — I’m going to introduce this subject by doing something that’s a little bit illogical but I just can’t resist it basically, so you are going to be subject to it. There actually is a logic to it, but to talk about the logic of resistance in the Revolution, I’m going to use a story that actually dates to a period significantly after the Revolution, which kind of doesn’t make sense but it does because the story actually really wraps up a lot of stuff in it.

And this story relates to a conversation that took place in 1791, so it’s after the Revolution. The United States has only been in existence for a few years when this story takes place. And Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, who is almost newly arrived as Secretary of State, not there for that long, decides he’s going to have a little dinner party to discuss a political question that’s come up, and he invites James Madison and he invites Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton. The reason why we know this story is because Jefferson told it a lot, right? Because as we’ll see, Jefferson draws great, deep significance to this little dinner conversation and he repeated it over and over again in letters and in journals. It’s like the story that reveals the meaning of everything — but you’ll see why. It won’t sound too dramatic now that I’ve set it up that way, but to Jefferson it was earth-shaking.

So a little dinner party, Madison, Jefferson, Hamilton — and Jefferson, who tells the story, says that after they’re done with their meal, quote, “our questions agreed and dismissed, conversation began on other matters. . . . The room, being hung around with a collection of the portraits of remarkable men — among them were those of Bacon, Newton, and Locke — Hamilton asked me who they were.” So this is Jefferson’s home and in his home are these portraits, Bacon, Newton, and Locke, and Hamilton, sitting there as a dinner guest, looks up, sees the portrait and says, ‘Who are they?’ Okay. Jefferson says, “I told him they were my trinity of the [three] greatest men the world had ever produced” (this is Professor Jefferson in full gear) “naming them.” Lord Francis Bacon, the philosopher of science, Sir Isaac Newton, the scientist who defined the laws of gravity, John Locke, the philosopher of — I suppose you could say, the philosopher of liberty, and as Jefferson recalled hearing this, quote, Hamilton “paused for some time. ‘The greatest man,’ said he, ‘that ever lived was Julius Caesar.'” Okay. Now for reasons that will become clear in this lecture, this shocked Jefferson, shocked Jefferson, so that he told the story again and again and again, remembered it for decades. In the 1820s, he’s still like, ‘I remember that story, the dinner with Hamilton 30 years ago [laughs] in which he said, ‘The greatest man who ever lived was Julius Caesar.’ He repeated it.

To him it was a sign of the amazing dangerous implications of Hamilton’s policies, but I want to pull this story apart. I want to look at this a little bit as a way not really of getting at Jefferson and Hamilton, but to get at something of the intellectual mindset of Americans during this period and some of this has to do with Enlightenment thinking, and some of this has to do with constitutional thinking, but you’ll see why both men said what they said.

Now to start with, I’m not saying that every single colonist is sitting around at this point discussing Bacon, Newton and Locke. Okay. That’s not what I mean. This is very much a Jeffersonian parlor with these portraits up on the wall, but those three men — Bacon, Newton, Locke — and others, did contribute to an intellectual atmosphere that the American colonists tapped into that shaped their thoughts about rights, about resistance, and then eventually about revolution.

So let’s start by looking at Jefferson’s trinity of great men. Who were they? Okay. Sir Francis Bacon, man of science who believed that truth discovered by reason through observation could promote human happiness as well as truth communicated through God’s direct revelation. So basically Bacon’s work suggested that it was in humankind’s power to discover truth by reason and that by doing that, humankind could better itself. Okay. So that’s Bacon.

Left: Portrait of Francis Bacon, by Paul van Somer, 1617 / Palace on the Water (Royal Baths Museum)

Center: Portrait of Isaac Newton, by Barrington Bramley / Institute for Mathematical Sciences, University of Cambridge

Right: Portrait of John Locke, by Godfrey Kneller, 1697 / State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Isaac Newton, a second man of science who studied gravity and the laws of motion, and Newton’s work demonstrated that it was possible through reason and study to discover the laws of nature and of nature’s God. So Newton’s work suggested that the world is governed by laws that you could discover and understand; that there’s a cause and effect, and that through reason and study you can figure out the cause and effect of nature’s laws.

So then on to the third man, John Locke, whose Second Treatise on Government from 1683 [correction: 1689] suggested that you could apply nature’s laws to the political world as well, and determine and understand natural and political rights. And I’m going to offer here a really woefully brief summary of Locke’s thoughts that’ll just be enough to give us a sense of what it is that Jefferson’s getting at here. Basically, Locke believed that people were born free, unhampered by government and with certain natural rights — life, liberty, and property — and that to protect these rights people decided to voluntarily leave this state of nature to form a civil government, contracting some of their natural rights to this government when they did so. So civil society was created to protect humankind’s three natural rights — life, liberty, property. So you could refer to this as social contract theory, a logical enough summing up of it. If you think about it, if a civil government is a kind of voluntary contract, this suggests that people have a right to pull out of that contract if their rights are being violated, and obviously that will have an important logic down the road.

Now if you take all of that together — Bacon, Newton, Locke, and the logic of their thoughts — you can see the empowering aspect of Jefferson’s trinity. Right? All of those men in one way or another are preaching ideas that are empowering humankind. They’re suggesting that there are laws of the universe that could be determined by people and applied to nature, to government, to science, to society in the hope of bettering things. They suggested that civil government is a contract created by and maintained by people, not some kind of a divine creation. And if you step back and consider the implications of these really broad ideas, you can see that they share an underlying conviction that humankind could solve God’s riddles by dissolving — dissolving? dissolving his laws, chaos — discovering and applying his natural laws.

And in a sense this is the idea that’s the spirit of the Enlightenment — that the world is governed by natural laws that can be detected, they can be studied, they can be applied, and in a sense the practice of deism stems from this idea. There were some Founder types who were basically deists at heart, believing that God was a sort of divine clockmaker who made a world of logic and natural laws and then stepped back and allowed it to operate without intervening, and this kind of God was omniscient and all powerful but it was natural forces that governed daily existence. And things that were governed by understandable and predictable natural laws could be detected, analyzed, critiqued and applied by man. So in this sense you really can see how some of the spirit of the Enlightenment would have been a kind of empowering philosophy.

Jefferson’s Reflection on Hamilton’s Favorite Hero

The Tusculum portrait, perhaps the only surviving sculpture of Caesar made during his lifetime / Louvre Museum, Paris

So Jefferson’s trinity of portraits reveals a lot about this kind of general Enlightenment spirit and some of its intellectual implications, but what about the other half of the story? What about Hamilton’s comment about Julius Caesar and Jefferson’s I’m-going-to-be-shocked-for-three-decades response? Well, this aspect of the story reveals another related aspect of the Enlightenment mentality. It shows how immediate and relevant the ancient world — and actually history generally — was to Enlightenment thinkers, and I suppose, just in the eighteenth century generally. An idea that’s — again — related to this idea that humankind can detect patterns and then apply them for all time. Because basically, if you think about it, if you believe in ongoing natural patterns, you’re also going to believe that the study of history, all of history, is one way to determine laws and patterns of human nature that apply across all time.

So basically to people at this period, all of history was like a big grab bag of lessons about humankind and civil society: ancient Greece, ancient Rome, modern nations, modern peoples and more. If you study them, if you look at rules and patterns, you could find things to apply to modern times that ideally would allow you to better things for the present by learning from the past. And in a way the ultimate example of this — I think I’ve mentioned it once before in here; I’m not sure — is James Madison preparing for the Constitutional Convention and he’s very much — he’s right in line with this kind of thinking. He basically says, ‘I’m going to study republics across all time,’ right? All of human time — I will study republican government — and thinking, if he could figure out the rules, if he could figure out what works and what doesn’t work and see the patterns and get the rules, he can then apply that knowledge to the creation of a new republic that hopefully then would benefit from that kind of knowledge. I love the fact that Madison sets out to do that, writes it all down on paper.

So you can see how in this sense — If you’re thinking along these lines, you can see how ancient history could be really immediate to this sort of whole founding generation, because it had real lessons for the present. And actually one of the most influential books in educating young gentlemen at the time was Plutarch’s Lives. Plutarch’s Lives is basically a collection of brief biographies of great statesmen and leaders, ancient Greece, ancient Rome, and it was aimed at teaching rules of leadership, teaching young men how to model themselves into great leaders, or certainly that’s how it was used in the eighteenth century. Any young man would have read Plutarch’s Lives and would have learned — the greatest thing I can do is to be a great statesman and found a nation, and here are great examples for me to follow.

So given this kind of a logic, there’s a good reason why Hamilton’s comment about Caesar might have been shocking to Jefferson. It’s not just a little interesting intellectual sort of “ha” on the part of Hamilton: ‘oh, I think the greatest man that ever lived was Julius Caesar, pass the cherries.’ It’s not — He didn’t see this as a sort of random idle throwaway intellectual comment. It was a declaration about present day policies to Jefferson, and it wasn’t a declaration that made Jefferson happy because think about the historical lesson that Jefferson logically pulled from Hamilton’s comment about Julius Caesar. Who was Julius Caesar? In short, he was the man who destroyed the Roman republic. Okay. He’s the guy who marched his army against the republic, who seized power, who made himself emperor. So there we are in 1791 and Alexander Hamilton in the middle of this experiment to create a new republic — no one knows if it’s going to work; it might collapse at any second — and Alexander Hamilton says, ‘The greatest man who ever lived is Julius Caesar,’ the man who destroyed the Roman republic.

Okay. This is why Jefferson was like [laughs]: ‘oh, my God. What does this mean?’ What does this mean? This is the truth to Hamilton. Right? This is a bad moment as far as relations between Jefferson and Hamilton are concerned, the Jefferson dinner party. Hamilton never lived it down. So to Jefferson this is — to him this was like he — the scales were lifted from his eyes. Right? Hamilton wants to be a kind of Caesar. He’s dangerously ambitious. He wants to destroy the republic. Maybe he wants to make it back into a monarchy and then put himself into some kind of a position of power. He could just see the pathway laid, all with that one little comment that Hamilton tossed out at a dinner. You had to be careful how you talked [laughs] in an age where history meant that much.

Now let’s stop for a moment also to think: why did Hamilton say that? Why did he say that? It’s unlikely that what he meant to say was, ‘Hi. I’m going to be the next Julius Caesar. [laughs] I’m out to destroy the republic. Nice to meet you.’ Okay. He probably wasn’t intending to signal some big threat to the American republic.

Portrait of Alexander Hamilton, by John Trumbull, 1806 / Washington University Law School

I think that there are probably two explanations for it. No one actually ever absolutely knows why he said this and that says more about Hamilton than anything else. He’s a wonderfully self-destructive individual, Alexander Hamilton, but in this case I think there are two possible reasons why he said this. One is he actually just liked to say things to upset Thomas Jefferson. [laughter] He really did and this was a good one, [laughs] better than he thought, but he liked to push Jefferson’s buttons, get Jefferson all sort of sputtering and mad, and it worked. Aaron Burr did the same thing to Alexander Hamilton. He would say sort of shocking, outrageous things and then watch Hamilton sputter, and then Hamilton would repeat them for years and years and years. ‘Do you know what he said at the dinner party?’ Dinner parties were tricky places to maneuver in the early republic.

So part of it might have been just Hamilton being deliberately irritating, or equally possible, it’s possible that Hamilton was referring to Caesar as a statesman, a leader, a founder of a nation. Hamilton would have admired military ability, so he would have actually seriously admired that in Caesar too, but he really could have been more thinking of Caesar as great statesman, great leader, depicted in Plutarch as a model. And certainly in the mind of an educated gentleman like Hamilton, being the founder of a nation, being someone who’s shaping a nation, would have been seen as an admirable thing, so he could have been thinking along those lines. It’s interesting when you look through all of Hamilton’s writings — he doesn’t really speak in praise of Caesar anywhere else, which might lead you to theory number one. [laughter] ‘Okay, T.J., see how you deal with this one. [laughs] I’m all for Julius Caesar. [laughs] What are you going to do?’ No.

It’s hard to know, but at any rate it’s unclear what Hamilton’s logic is, but you can certainly understand Jefferson’s shocked response, and either way, both the comment and the response reveal the power of the classical heritage on this early American world. Both men are applying the past to the present in some way. And one of the lessons that Caesar certainly suggested to Thomas Jefferson as suggested by his response is a powerful lesson that a lot of people were focused on in the early years of the American republic and in this colonial period as well, and that is the fragility of liberties — and in the republic also obviously how fragile republics are. So the ancient world held really valuable lessons but so did the semi-recent past as well, particularly for the American colonists.

There was another period of time that seemed to hold special lessons for them, the period of the Glorious Revolution in Britain, which would have been a period when opposition to the King’s Court and ministers was on the rise in Britain along with a growing tradition of praise for English liberties and the glories of representation in Parliament. So political rhetoric from the era of the Glorious Revolution would have focused on attacking corruption and corrupt influence, as when a monarch would try to bribe legislators or ministers with high office or pensions granted from the Crown, thereby subverting the balanced British constitution, which is supposed to be balanced between Crown, Lords and Commons. That would have had some real bearing on this revolutionary period as well But whether talking about history ancient or history relatively modern, history did teach some overriding lessons that British subjects would have taken as their own throughout this period and that at this moment in time would seem really relevant in the American colonies.

The Logic of Colonial Unity from the British Perspective

Prince of Orange Landing at Torbay in the Glorious Revolution, engraving by William Miller after J M W Turner (Rawlinson 739), published in The Art Journal 1852 (New Series Volume IV). George Virtue, London, 1852 / British Library

You’ll see really clear lessons that history would appear to be teaching generally and that the colonists would be listening to really attentively. So history taught basically that arbitrary power is the ultimate threat to good government. Okay. So the 1770s is a moment when that’s certainly going to be something that people hear. History taught that political liberties were fragile. History taught that constitutional principles defended customary contractarian rights against government assertions of arbitrary power. So arbitrary power is the ultimate threat to good government; political liberties are fragile; and it’s constitutional principles that defend against government asserting arbitrary power. So yes, Rome had been great, but arbitrary power had sent it spiraling into tyranny. The Glorious Revolution had been a moment where ancient liberties had been restored by restraining the power of the monarch. So clearly history taught liberty is fragile, and power is the natural enemy — arbitrary power — and power naturally grows, by nature power grows, and as it does it encroaches on liberties in a free society.

So power has to be restrained; British liberties must be defended; and British liberties, as defined by generations of constitutional precedents. Now it’s important to remember that the British constitution is not a written document like American state and federal constitutions. It’s a way of thinking about authority largely based on precedent, based on existing institutions, based on laws and customs, and it was a means of limiting power and defending rights.

So when British colonial policy began to change in the mid-eighteenth century and precedents seemed to be abandoned and new precedents perhaps were being set, when Parliament seemed to be asserting what certainly to some colonists felt like arbitrary power, colonists logically began to worry about protecting their fundamental British liberties against seemingly increasingly arbitrary parliamentary power. They felt defensive. They worried about the seeming inevitability of a rise of arbitrary power.

Now of course people in Parliament did not see themselves as exercising arbitrary power. They saw themselves as behaving constitutionally, asserting their constitutional power to govern over the colonies, but as we’ve seen in this course so far, there were some fundamental disagreements on both sides about the precise meaning of Parliament’s constitutional power to govern over the colonies, about the precise way in which this imperial system was supposed to work. So acts like the Stamp Act, which Parliament basically intended as a way to raise revenue, or the Tea Act, same idea, could logically seem to the colonists like a way of establishing a new precedent, right? — a new precedent that ultimately would be making some kind of inroad against liberty and property rights. And particularly, given that the Stamp Act was not ultimately raising enormous sums of money to the colonists, that was a real sign that it must be about a precedent. Right? It can’t really be about raising enormous sums of money. It must be a trap, a precedent-setting trap, that if they can get us to accept this precedent then the government will be able to set future taxes along similar lines because the precedent will have been set. If your constitution — If you understand your constitutional rights as based on precedent, when you see new precedents potentially being set that’s a potentially scary thing, so you can kind of get a sense of why the colonists are reacting as they do to a lot of events in this period.

Image of the first page of John Dickinson’s Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania / Dickinson College

As John Dickinson wrote in — I’ve mentioned before his really well-known pamphlet from 1768 called Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania. Dickinson wrote, “Nothing is wanted at home” — and by home he means Britain — “but a precedent, the force of which shall be established by the tacit submission of the colonies. . . . If the parliament succeeds in this attempt, other statutes will impose other duties. [A]nd thus the parliament will levy upon us such sums of money as they chuoose to take, without any other limitation, than their pleasure.” Right? He says it’s just about the precedent; it’s all about precedent. That’s what we’re looking at here. The fact that small amounts of money are being raised in a sense is the ultimate proof that what really matters to Parliament is the precedent that they’re setting.

The same holds true for the Vice-Admiralty courts I’ve mentioned before, that were being used as venues for trying certain crimes committed in the colonies. Vice-Admiralty courts were composed of a single judge, they had no jury, and they were becoming responsible for enforcing parliamentary legislation and new legislation. Logically, many colonists would have seen this — again — really dangerous precedent violating fundamental British constitutional rights, violating past precedents.

The presence of a standing army in the colonies: also, same kind of threat, same kind of fear, something new is happening here, and certainly history ancient and modern taught about the dangers of a standing army. And Samuel Adams summed up prevailing ideas about standing armies in a newspaper essay that he wrote in 1768 and he wrote,

“It is a very improbable supposition, that any people can long remain free, with a strong military power in the very heart of their country: Unless that military power is under the direction of the people, and even then it is dangerous. — History, both ancient and modern, affords many instances of the overthrow of states and kingdoms by the power of soldiers, who were rais’d and maintain’d at first under the plausible pretense of defending those very liberties which they afterwards destroyed.”

So in the colonies the fear of a standing army was bad enough at the end of the French and Indian War when the crown sent troops to protect the colonists against the French, the Spanish and the Native American populations — but a few years later when troops began to arrive in Boston in response to Stamp Act demonstrations, it certainly seemed to many colonists as though it might be the first step in what could be the destruction of their liberties, their colonial charters, their constitutional rights. This seemed to be — again — a scary precedent.

Now in a way it’s really tempting to look at this way of thinking like, these people are worried about precedents — ‘What’s happening? What does it mean? It must be a sign that they’re going to do worse’ — and think of these people as being really paranoid and illogical like, ‘oh, come on. [laughs] What if it’s just a little gesture to raise some money, colonists? Why do you seem so paranoid?’ And there — In the past there actually have been some historians who suggested that the colonists were to some degree being paranoid, were seeing threats of tyranny where there actually wasn’t any tyranny at all. But as I’ve just described, precedents are a fundamental part of British constitutional thought. And Enlightenment theory backed up that idea, because Enlightenment science promised the capacity to understand and control nature and society. You’re supposed to be looking for patterns of behavior to understand what things mean.

So the British government seemed to be setting new precedents and the colonists were looking for the pattern, trying to figure out the logic of what was happening. What was Parliament up to? What were they thinking? Why were they seemingly violating fundamental constitutional rights? And you can see this logic again in Dickinson’s pamphlet, in hisLetters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, which he argued was premised on his desire, quote, “to discover the intentions of those who rule over us.” Why are they doing what they’re doing? There’s a pattern. What is the pattern? What does it mean?

Colonists ultimately resisted what they saw as the approach of tyranny, and their resistance stiffened the British government’s resolve, which in turn provoked more of a reaction in the colonies. And eventually down the road, the colonists would come to see their social contract with the British government broken, a conclusion which would seem to then give them the right of community resistance, but as I’ve said before it’s important to recognize that the colonists at this point see their actions not as revolutionary but just the opposite. They’re fighting for their British rights. They’re not trying to figure out how to stage a revolution. I think when we hear the phrase “Continental Congress,” we’re like: ‘ooh, one more Continental Congress and we’re there, [laughs] wow, almost at independence,’ — but that’s obviously not the way that they’re thinking at the time. They see themselves as fighting against arbitrary power in defense of British liberties, not as rabid revolutionaries, and thus far in the course, it’s Parliament that seems to be the main source of arbitrary power to the colonists.

A logical response to this conclusion would be for the colonists to next turn to the King to solve their problems. Okay. If Parliament is exercising arbitrary power we will now turn to the King and appeal to him to solve our problems. So more has to happen before the colonists begin to consider the ultimate act of resistance. Actual rebellion would seem to them as the last resort, the last resort of a people unable to protect their lives, liberties and properties by normal constitutional methods, and there were some Members of Parliament that could foresee this looming threat.

Edmund Burke’s Warning

Portrait of Edmund Burke, by Joshua Reynolds, 1768 / National Portrait Gallery, London

In early 1775, Edmund Burke gave one of his best known speeches in Parliament. It was a three-hour speech and he argued in his speech that Parliament should try to be conciliatory towards the colonies or risk pushing them to extremes. And he laid out in this speech some of the points that actually have come up just in the course of this lecture. He said Americans loved their liberties. Why? Because they’re descendants of liberty-loving English citizens. To those who argued that giving concessions to the colonists would encourage them to demand even more concessions, Burke said, he doubted whether, quote, “giving. . . two millions of my fellow citizens, some share of those rights, which I have always been taught to value,” would bring down the empire. And he had a dramatic conclusion. He said, “Let the colonies always keep the idea of their civil rights associated with your government; — they will cling and grapple to you; and no force under heaven will be of power to tear them from their allegiance But let it once be understood that your government may be one thing, and their privilege another; that these two things may exist without any mutual relation; the cement is gone; the cohesion is loosened; and everything hastens to decay and dissolution.”

So to the colonists then in a sense — you can hear, to Burke as well — rebellion would be a drastic action only to be exercised by an overwhelming majority of the community against rulers who so completely ignored the terms of the original social contract as to make further allegiance a crime against God and reason. And it’s really only by grasping this mindset and really taking it seriously that we can begin to understand events to come that ultimately will lead to what is seen at the time as that last dire step towards revolution.