The North American Colonies and the British Empire

The European countries of Spain, France and Britain all had important interests in North America, not least because these colonies promised future wealth and were strategically important to the sugar, tobacco and coffee islands of the Caribbean.

By the mid-eighteenth century, the British North American colonies were well-established settlements, closely tied into Atlantic and Caribbean trading networks. Although religious beliefs provided the motivation for many settlers, others also saw the colonies as an opportunity to own their own land, work for themselves or find their fortune. From fish and furs to tobacco and timber, it seemed that great wealth could be made from securing exclusive mercantile access to these lands, which also traded closely with the sugar isles of the Caribbean.

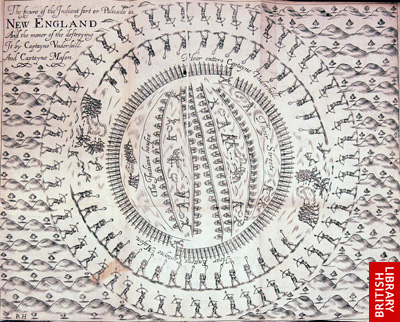

Competition over these resources intensified the conflict between Britain, France and Spain (the major European powers in the Americas), and the British colonies had to be defended from French and Native American attacks.

Who should meet these costs became the question of the day.

The Pamphlet War and the Boston Massacre

‘Being master of my time, I spend a good deal of it in a library, which I think the most valuable part of my small estate’

John Dickinson

Colonists had thought of themselves as part of the extended British nation, but by the outbreak of Revolution, many came to see themselves as Americans, with different interests to the colonial powers. The ideas behind this transformation were spread by pamphlets of all kinds.

The Stamp Act Crisis underlined the differing interests of the colonists and Parliament and helped to reinforce a growing sense of American identity. Although the government repealed the Stamp Tax, the Townshend Revenue Acts (1767), which placed duties on tea, glass, lead, paper and paint, and the Tea Act (1773) added to the colonists’ grievances.

Wildly popular pamphlets such as John Dickinson, Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania (1767) gave voice to these complaints. Patriots founded circulating societies, helping to spread news and revolutionary comment.

On 5 March 1770, harassed British troops guarding the Boston Custom House fired a volley into crowd that had gathered. Five men died. The incident, soon called the Boston Massacre and depicted in patriotic prints, came to symbolise British tyranny.

In 1774 the ‘Intolerable Acts’, which removed Massachusetts’ right to self-government, further radicalizing dissent. Men such as Sam Adams and Paul Revere called for complete independence from the British Crown. The Library holds several examples of such items (and many more in surrogate as part of the Early American Imprints series).

Such writings helped to define American Republicanism, helping to justify calls for independence and to conceptualise the new American nation state. According to contemporary political theory, republics were preferable to monarchies, but they were also easily corrupted and prey to powerful vested interests. To counter this danger, the new nation required a virtuous citizenry. This quality of ‘virtue’ was to be found in the independent and self-sufficient hearth of the craftsman or farmer, rather than in the large houses of merchants or plantation owners.

Thomas Paine’s Common Sense (1776) encapsulated the American argument, vigorously arguing in an accessible style for a nation in which the people were sovereign and the aristocracy had no place. Paine believed that a democracy government could take root in the North American continent because of the virtuousness of the American people.

The American Republic

Victory brought questions about the nature of the American state, including the relationship between individual colonies and national government. These and other issues, particularly slavery, remained fissures within the new body politic

The Revolutionary Wars left the colonies in a wretched state. For many Americans, the war brought hardship and suffering even if they were not fighting; more died of disease than from enemy fire. 60,000 Loyalists left the United States. Many settled in Canada, while others had their property confiscated. Popular protest within the States, such as Shay’s Rebellion (1786) against high taxes in Massachusetts, also challenged the old colonial power structures, demanding wider property ownership and more political representation.

These conflicts also took place at the federal level, as the second Continental Congress (1775-1781) and Confederation Congress (1781-1788), wrestled with the question of how the new nation should be governed and what powers the individual states should retain. Fearful of replicating the ‘tyranny’ of centralized authority represented by British colonial rule, the initial Articles of Confederation (ratified 1781) enshrined the sovereignty of individual states.

Lacking the means to enforce its decisions, national government soon broke down, and the Constitutional Convention, which met in 1788 at Philadelphia, chose to replace the Articles with the Constitution of the United States. The Constitutional Convention favoured a strong, national government over a loose federation of states. The constitution was guided by the Enlightenment principle of a separation of powers, with the presidency, congress and supreme court provided with their own areas of responsibility, but able to restrain the other branches of government.

Fearful of the concentration of power and influence of the larger states, Antifederalists successfully campaigned for ten amendments to the constitution, known as the Bill of Rights and which guaranteed basic freedoms such as of speech and worship (the ‘First Amendment’) and the right to a ‘speedy and public trial’ (the ‘Sixth Amendment’).

Finally, slavery played an important role in the debate on the balance of power between the smaller states and the larger, southern ones. Enslaved black population were counted proportional as three fifths of state population to determine number of representatives and also counted as property for tax purposes. Abolition of the importation of slaves was barred until 1808.

The British Revival

The loss of the colonies rocked the ship of state, but did not cause it to capsize, despite hyperbolic talk of civil war or rebellion at home and a growth in radical agitation. Indeed, some historians argue that support for the crown grew. Political life quickly settled into much the same patterns as before the war, albeit with a greater emphasis placed on public opinion, a stronger sense of political parties and more concern with economic reform and corruption. Demobilisation caused temporary difficulties, but low tariffs helped to stimulate trade and the economy recovered rapidly: by the 1790s, Americans were purchasing twice as much from Britain as they had as colonists in the 1760s.

Ironically, perhaps, the war bolstered British self-image, seeing itself as a beleaguered nation attacked facing alone an unprecedented alliance of America, the French, the Spanish and the Dutch. News of Admiral Rodney’s victory in the Saints Isles off Guadeloupe and the successful defence of Gibraltar was received euphorically, pointing to a growing sense of national identity and pride.

Attitudes towards empire also shifted. In the long term, imperial ambition did not decline, despite the loss of the thirteen colonies, and British interest and influence in India continued to increase. Arguably, Britons began to think of empire more in terms of conquest and annexation rather than white colonies and in consequence imperial structures became more authoritarian. America also continued to attract British settlers.

The Revolution also had unexpected and far-reaching consequences. Deprived of a dumping ground for British convicts (Franklin remarked that Americans should send back rattlesnakes in return for the 50,000 men and women Britain had resettled there), from 1787 Botany Bay became a convict camp, helping to found British Australia. France’s relative weakening through the costs of war enhanced Britain’s strategic position; France’s embattled finances would also precipitate the French Revolution in 1789, leading to even greater challenges to the British nation.

Peace of Paris

Peace negotiations in 1782 led to the ‘Peace of Paris’ and a famous map with borders marked in red.

The red line was used by the British negotiating for peace with the Americans to demonstrate their interpretation of the boundary between the United States and the provinces which later formed Canada. The map was presented to George III to show him how the proposed boundaries might work.

As Britain recognized its military failure, it successfully pursued peace negotiations with France, Spain and the United States, and later came to terms with the Netherlands. Although Britain lost the United States, it maintained much of its international influence. Britain also reassessed its relationship with its army and empire.

On 5 March 1782, twelve years after the Boston Massacre, Britain entered into peace negotiations with the French and Americans. The former North American colonies were not at the centre of the major powers’ strategic concerns, and the United States negotiators, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin and John Jay, took full advantage of France and Britain’s fears of growing Russian influence over the Ottoman Empire and need for rapprochement in order to secure the greatest advantage to their young nation. The French and British ministers, Vergennes and Shelburne, also believed that a United States of America offered lucrative opportunities for trade and that a generous treaty would encourage economic links.

In the resulting Peace of Paris (1783) Britain recognised US independence and agreed to cease hostilities and withdraw her troops. The United States recognised the debts owed to British creditors and promised to ‘earnestly recommend’ the restitution of property seized from those who had remained loyal to Britain. Much of the US-Canadian border was confirmed, and Britain renounced its Mississippi claims and returned East and West Florida to Spain. The last British troops sailed from New York City on 25 November 1783.

Despite the British negotiators’ belief that they had gained the benefits of North American commercial relations without the cost of defending colonies, the treaty attracted popular and political hostility. Numerous pamphlets attacking the king and his ministers can be found in the British Library’s collections, as well as loyalist publications. Shelburne’s personal and political papers are also held by Manuscripts Collections. Papers relating to John Jay’s Treaty, which helped to normalise Anglo-US relations and liberalise trade can also be consulted.

Originally published by the British Library under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.