Multiple back-and-forth movements are not surprising, and multidirectional migrations make pinpointing origins difficult.

By Patrick Scott Smith, M.A.

Writer and Researcher

Introduction

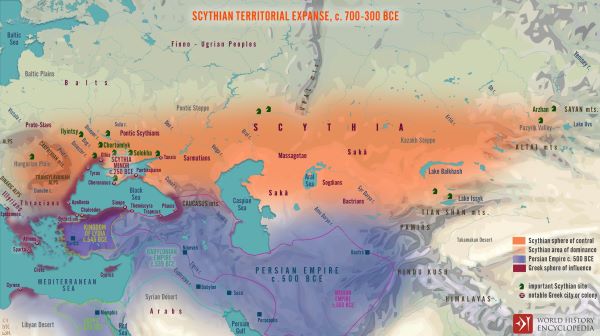

With 7600 perimeter miles (12,231 km), the Scythians roamed and ruled over an astonishing 1.5 million mi² (2.4 million km²) of territory between the 7th and 3rd centuries BCE. Although building an empire was never in their interest, Scythian territorial expanse was remarkable, and they were unconquerable due to several factors: their form of governance, social structure, and military machine.

Origins

While there is much debate concerning Scythian origins, “Herodotus claims, and most modern scholars agree: they moved [west] from Asia into Europe by way of the great steppe corridor” (Alexeyev, 23). Yet, in the 1st century BCE, the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus states the first Scythians moved north from the Araxes river of Armenia to the northern Black Sea area. A modern traditional view is that they were “descendants from the Scrubnaya culture which, between the middle of the 2nd millennium B.C. and the end of the 7th century B.C., moved [south] in several waves from the Volga-Ural steppes into the north Black Sea” (Melyukova, 99). Writing in the 5th century BCE, Herodotus also shows the Sarmatians, splitting from the Black Sea Scythians, moving east. Then recent archaeological discovery at Tuva in the Altai Mountains, which dates Scythian settlement to the 9th century BCE, suggests early origins in the east. However, as 1st-century CE Chinese chroniclers speak of their red hair and blue eyes, their Caucasian features and Indo-European language support earlier Bronze Age origins in the west, likely from the Celts.

Considering the fluidity of movement the Central Asian steppe allows, multiple back-and-forth movements are not surprising, and multidirectional migrations make pinpointing origins difficult. Finally, it is altogether possible that, after an early pervasive expansion from the west, there were subsequent migrations from all directions. While their origin is debated, a general consensus identifies Scythian cultures to be generally comprised of four main groups:

- Pontic Scythians around the Black Sea

- Sarmatians from the northern Caspian Sea and Don and Volga River areas, in present-day Russia

- Massagetae in the desert steppe of Central Asia

- Sakā in east Central Asia

Scythian Government

One of the things that made the Scythians able to hold on to a home territory so large in proportion was a form of governance that promoted group identity and tribal loyalty. Rather than a consolidated rule – like that practiced by the Persian Empire and Romans – Scythia’s governance was mainly a form of shared power. Although Herodotus refers to Scythian ‘kings’, and some by name, Scythian government was more a confederation of tribes and chiefs, a common form of social organization in Central Asia. Herodotus’ account reveals that while a high king or chief represented the Scythian nation in the messaging between notables, other subchiefs also voiced their opinion and had a significant say in implementing action.

Just as important as their tribal structure, their military’s communal organization would have been an unsung part of Scythia’s success. A golden beaker manufactured in the 4th century BCE from the Kul’-Oba kurgan in Crimea shows scenes of camaraderie among bivouacked soldiers. Another artifact in gold relief from the same kurgan demonstrates a common ritual where two warriors drink together from a horn. Such depictions reveal ways of life intended to instill a shared purpose where individuals fighting for friends against foe create a united, more resilient front. Nevertheless, while Scythian loyalty between soldiers was indeed robust, group loyalty was to their tribe and chief. Such cohesion was key in protecting territory against outside incursion.

Scythian Society

Perhaps more than anything else that defined the Scythian way of life and the limits of their terrain was the steppe topography over which they roamed. Moreover, their practice of a nomadic confederated tribalism and their close marriage to the steppe perhaps explains their reluctance to extend rule outside a territory with which they were familiar. Herodotus explains:

The Scythians have made the cleverest discovery: they have contrived that no one who attacks them can escape, and no one can catch them. For when men have no established cities or forts, but are all nomads and mounted archers, not living by tilling the soil but by raising cattle and carrying their dwellings on wagons, how can they not be invincible? They have made this discovery in a land that suits their purpose and has rivers as their allies; for their country is flat and grassy and well-watered. (Histories, 4.46.2-47.1)

While other sources also mention their houses on wheels, these wagons were not the American pioneer type to get to a settled place. Pulled by teams of oxen, some house-wagons could have two or three rooms. Depending on the rank of the dweller, floors and walls could be opulently adorned. Moreover, when gathered, the house-wagons would have the appearance of a city. Thus, compared to the urban centers of the more socially stratified agricultural societies, the very nature of their lifestyle – nomadism by house-wagon – may have engendered for the Scythians a higher degree of shared purpose and a more open society. Though there were chiefs, as a nation, everyone lived similarly and moved simultaneously. Though wagon size varied, for practical reasons, it was never extreme. When in their nomadic mode, there were no grand palaces with high walls requiring a protocol of social separation for the elite.

When they did settle, celebratory or ceremonial activity would have been events shared by all. Furthermore, the excessive hoarding of wealth by a few would have a socially discordant effect on an interdependent community of people on the move, and when it came to the everyday activity of animal husbandry, trade, crafts, hunting, and war, everyone’s contribution was visible and essential. Not only were they an extremely interdependent people sharing a common cause vigorously defending their own territory but the Scythians were also hard to beat because of their nomadism. Being on the move and difficult to locate, with no cities to conquer or agricultural interests to capture, an invading army would have to ask, why? Additionally, Scythia’s own war machine was consummate.

Scythian Warfare

In gaining and protecting their territory, the Scythians used military ware that included a wide array of weapons. Besides their horsemanship and skilled use of the bow, they used battle axes, maces, lances, swords, shields, and scale armor and helmets for personal protection, but it was because of their nimble cavalry and their collective ability to stay on the move that they were, as Herodotus said, “invincible and impossible to approach” (4.46.3). With such weapons and tactical ability on display, it is not surprising different nations often solicited Scythian military services. For example, in 490 BCE, Sakā mounted archers assisted the Persians against the Greeks at the Battle of Marathon and again at the Battle of Plataea in 479 BCE. Scythian warriors were similarly among the roll call joining Darius III (r. 336-330 BCE) against Alexander the Great at the Battle of Gaugamela in 331 BCE.

However, the Scythians were not just potent allies. In protecting and gaining territory, they had spectacular wins of their own. Thwarting a Persian invasion, Tomyris, the warrior-queen of the Massagetae, helped consolidate Scythia’s southeastern frontier in the Syr Darya river area by defeating Cyrus the Great (r. c. 550-530 BCE) in battle. Sharing a similar quadrant of territory with the Massagetae, Scythia’s southeasternmost flank was also protected by the more mercenary-like Sakā Scythians. Then as the Persians of the Achaemenid Empire came at them again from the north, Scythia’s northwestern frontier was firmly established when Darius I (r. 552-486 BCE) was forced to withdraw from Scythian territory by Idanthyrsus and his fellow chiefs. Adding to that, Ateas (c. 429-339 BCE), king of the Pontic Scythians, expanded Scythian territory into Thrace, establishing one of Scythia’s westernmost reaches, from the Don to the Danube. Finally, it was the Sarmatians who consolidated Scythia’s north-central frontier. Descended from the Amazons, who had warred then intermingled with the Pontic Scythians, the Sarmatians migrated northeast from the Black Sea to occupy the Volga and Ural Rivers area.

Territorial Expanse

Overview

In many instances, maps of the ancient world like that of Scythia are at best approximations. While Scythia’s wars and origin stories by the ancient sources help to determine general areas of dominance, archaeological discovery contributes to an improved estimate of territorial limits. Burial sites with the same cultural signifiers known as ‘Scythian’ can be used to represent the general geographical limits of cultural dominance. Moreover, the use of burial sites representing specific boundary markers can be relied on with the certainty that significant burial centers share the same geographical approximation with parent centers of power, as exampled in the north Black Sea kurgans and the Pontic Scythians area of power.

Additionally, as Scythian territory depends on what defines ‘Scythian’, specific cultural markers come into play: art style, war style, religious beliefs, subsistent techniques, and everyday cultural markers such as fashion, dress, and forms of entertainment. Ethnic markers are significant as well. As far east as Mongolia and China lived the Scythians of European descent. The qualifying factor these people certainly shared was their cultural characteristics as they were copied by others and at the same time intermingled with others. Thus, the interred at Pazyryk though primarily of European origin, used luxury items from China and have Mongolian DNA. Finally, therefore, while what it means to be ‘Scythian’ is, to a degree, relative, Scythian cultural and boundary markers can at the same time be fairly defined.

Southern Boundary

From west to east, the southernmost Scythian boundary would have been defined by the Balkan Mountains west of the Black Sea in Bulgaria, the Black Sea, the Caucasus, the Caspian Sea, the desert area east of the Caspian Sea to the Aral Sea, and east from there, the Syr Darya River area to the southeasternmost burial site at Issyk, by Issyk Lake. While the Scythians may have maintained some temporary dominance south of the Caucasus and to a degree south of the Black Sea, the mighty Achaemenid Empire, then the Seleucid Empire and Parthia impeded permanency in these areas. The Sakā Scythians dominated the vicinity of the Aral Sea, but the Syr Darya River area east of there remained a natural area of dispute with the Sogdians and Bactrians to the south.

Eastern Boundary

The easternmost boundary is defined by the Sayan-Altai-Dzhunger-Tian Shan Mountain ranges, or what we will call the greater Altai Mountain range, at the Mongolian/Chinese western borders. Multiple settlements have been found along this north/south path defining Scythia’s eastern boundary. In the Tuva region, one of the northernmost sites, Arzhan – 35 miles (56 km) from the Yenisei River and 100 miles (161 km) north of Uvs Lake – helps determine the northeast corner of Scythia’s boundary. Southwest a bit from Arzhan is the famous Pazyryk site. While the easternmost range, from the northeast corner at Arzhan to Issyk at the south, angles from east to west as it follows the greater Altai Mountain range, the distance between the Arzhan settlement to the north and the Issyk settlement to the south is approximately 1000 miles (1609 km).

Northern Boundary

From east to west, the steppe defines the northernmost boundary (Kazakhstan, Russia, and Ukraine today) and the rivers flowing south through the steppe, emptying into the Caspian and Black Seas. As the Scythians were primarily nomadic warriors, the steppe transitioning into forest determines their northernmost boundary and how far up these river areas the Scythians ranged. At the southern end of the Ural Mountains, where the Ural River bends and flows west for 300 miles (483 km), at the western bend, before flowing south again to empty into the Caspian Sea, “an unusual concentration of Kurgan burials” was found. This corridor, determined by the Ural Mountains to the north, “links the Pontic steppe and Kazakh steppe” and marks the middle of Scythia’s northern border. (Cunliffe, 26).

The distance from this east/west bend of the Ural River to the Caspian Sea is approximately 300 miles (483 km). West of this corridor is the Volga River, also emptying into the Caspian Sea. The distance between the Volga and Ural Rivers varies from 150 to 300 miles (241 to 483 km). Cunliffe mentions the Sarmatian territory extending to “the lower reaches of the Volga” (121). It is natural the Scythians would have maintained a similar northern range from the Ural River west to the Volga River. West of the Volga, to the Don River area, Herodotus says the Sarmatian Scythians traveled 15 days journey from the upper reaches of the Sea of Azov. (4.21) The accepted view for a day’s journey of the ancient world is 20 miles (32 km). Interestingly, 300 miles (483 km) north of the Sea of Azov maintains a similar degree of latitude for the Scythian northern border, as at the Volga and Ural Rivers.

Western Limits

As we move west, establishing a sense of margins for Scythia’s northern boundary, as the steppe narrows on reaching Eastern Europe, the north/south boundaries taper as well. Yet, boundaries were not just an indication of political and military limits but served as buffer zones of protection meant to absorb and repel incursion. Therefore, for the Scythians, one would assume an attempt at similar margins at the northwest part of the Black Sea as they did along their northern boundary. Thus while the royal burials of Chertomlyk and Solokha are on the east/west section of the Dnieper, which is approximately 100 miles (161 km) north of the Black Sea, the Ilyintsy, Zhurovka, and Melgunov burials, between the Dnieper and Bug Rivers, are in the vicinity where the Sula River empties into the Dnieper. At this confluence lies the modern city of Zhovnyne, Ukraine, 120 miles (193 km) downstream from Kiev. Zhovnyne is 200 miles (322 km) north of the Black Sea’s northern shore and around 400 miles (644 km) to a line approximately parallel with the Balkan Mountains to the west and the Caucasus to the east.

While no ancient sources confirm Scythian presence in the Carpathian basin west of the Black Sea, with the passable Carpathian Mountains to the north archaeological survey has found “all the main attributes of Scythian material culture” in the Carpathian Basin, itself of steppe topography, also known as the Great Hungarian Plain. (Cunliffe, 150) This represents Scythia’s westernmost boundary. This area is 400+ miles (644+ km) west of the Black Sea. The southwestern-most extent of Scythia’s western territorial expanse was likely impeded by the Balkan Mountains west of the Black Sea, and the Caucasus between the Black and Caspian Seas.

Conclusion

While the Scythians were more a confederation of tribes sharing common cultural characteristics, their nomadic lifestyle also encouraged a high degree of shared purpose. Being on the move and having no urban centers to conquer, such social cohesion combined with the hit-and-run tactics by their consummate cavalry made the Scythians formidable defenders of their homeland. Since theirs was a nomadic horse-culture dependent on plains settings, two things defined the extent of Scythian territory: steppe topography and natural boundaries enclosing the steppe. Thus, the Scythians flourished where the flat plains of Eurasia facilitated the migrations of their house-wagons and the quick and nimble movement of their horse archers.

Starting at the northwest corner burial area where the Sula River empties into the Dnieper, a natural enclosure to the north is where the steppe of Eurasia transitions into the forest belt of Eastern Europe and Siberia. To the east, it is enclosed by the greater Altai Mountain ranges, from the Arzhan burials in the north to the Lake Issyk burials in the south. The distance between these two corners of Scythia’s eastern frontier is 1000 miles (1609 km). Moving west from Lake Issyk, Scythia’s southern boundary would have been generally defined by the Syr Darya River as it empties into the Aral Sea, the desert areas east of the Caspian Sea, and more specifically defined by the Caucasus between the Black and Caspian Seas and the Balkan Mountains west of the Black Sea. If we include the Hungarian Plain as a Scythian abode, Scythia’s westernmost reach would have been 400 miles (644 km) west of the Black Sea. Thus, while the length of Scythian territory would have been 3000 miles (4828 km) from Arzhan to the Hungarian Plain, its width was 1000 miles (1609 km) in the east, tapering to 400 miles (644 km) width in the west.

Bibliography

- A. Yu Alexeyev. “The Scythian in Eurasia.” Scythians, edited by Simpson, St. John & Pankova, Svetlana. Thames & Hudson, 2017.

- Appian of Alexandria. Delphi Complete Works of Appian. Delphi Classics, 2016.

- Cassius Dio. Delphi Complete Works of Cassius Dio. Delphi Classics, 2014.

- Cernenko, E.V & McBride, Angus. Scythians 700-300 B.C. Osprey Publishing, 1983.

- Cunliffe, Barry. The Scythians. Oxford University Press, 2019.

- David C. Braund. “Scythia.” The Oxford Classical Dictionary, edited by Hornblower, Simon & Spawforth, Antony & Eidinow, Esther. Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Farkas, Ann, Et Al; Metropolitan Museum of Art. From the lands of the Scythians. Metropolitan Museum of Art : distributed by New York Graphic Society, 1975.

- Herodotus. Delphi Complete Works of Herodotus. Delphi Classics, 2013.

- Melyukova, A.I. “The Scythians and Sarmatians.” The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, edited by Sinor, Denis. Cambridge University Press, 1990.

- Renate Rolle. “The Scythians: Between Mobility, Tomb Architecture, and Early Urban Structures.” The Barbarians of Ancient Europe, edited by Bonfante, Larissa. Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- Tacitus, Publius Cornelius. Delphi Complete Works of Tacitus. Delphi Classics, 2014.

Originally published by the World History Encyclopedia, 10.05.2021, under a Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.