Christian apocalypticism has evolved from early Jewish eschatological roots.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The concept of apocalypse—derived from the Greek word apokálypsis, meaning “unveiling” or “revelation”—has been central to Christianity since its inception. Far from being merely a fixation on cataclysm or end-times speculation, apocalypticism in Christian history represents a rich theological, social, and political tradition. It encompasses visions of divine judgment, cosmic renewal, and the hope of deliverance for the faithful. Over centuries, Christian apocalypticism has evolved from early Jewish eschatological roots into a potent force shaping ecclesiastical doctrine, political movements, and cultural imagination. This essay explores the historical development of apocalypticism in Christianity from its Jewish antecedents through its role in early Christian writings, medieval thought, Reformation movements, and modern interpretations.

Jewish Roots of Christian Apocalypticism

Christian apocalypticism cannot be fully understood without a thorough appreciation of its Jewish antecedents, particularly those that developed during the Second Temple period (circa 516 BCE to 70 CE). During this time, Jewish communities experienced repeated conquests, exile, and foreign occupation—from the Babylonians and Persians to the Greeks and Romans. These traumatic historical events fostered an eschatological worldview in which history was understood as a cosmic struggle between divine and evil forces. Rather than viewing suffering through purely moral or covenantal lenses, Jewish apocalyptic literature increasingly interpreted adversity as part of a divine timetable that would culminate in divine judgment and the restoration of Israel. Apocalypticism offered a theological response to powerlessness, reasserting that God’s justice would ultimately triumph, even if it remained hidden in the present age. In this sense, the genre became a vehicle of both protest and hope, shaping Jewish expectation of divine intervention in history.1

Key texts exemplifying this genre include the Book of Daniel, portions of Isaiah and Ezekiel, and non-canonical works such as 1 Enoch and 2 Esdras. The Book of Daniel, likely composed during the Maccabean Revolt (circa 167–160 BCE), is paradigmatic of Jewish apocalypticism. It blends court legend with visionary prophecy, presenting a series of dreams and symbolic visions about successive empires culminating in the establishment of God’s eternal kingdom.2 Particularly notable is Daniel 7, which introduces the enigmatic “Son of Man” figure who receives divine authority and everlasting dominion—an image that would later be pivotal in Christian messianology.3 These texts rely on coded symbolism, pseudonymous authorship, and the promise of eschatological reversal—elements that would profoundly influence Christian apocalyptic writing, especially in the Book of Revelation.

In addition to canonical texts, pseudepigraphal literature such as the Book of the Watchers (part of 1 Enoch) played a significant role in shaping Jewish apocalyptic thought. This text elaborates on the myth of fallen angels (Genesis 6:1–4), introducing a cosmic conflict between angelic and demonic beings that disrupts human order. It emphasizes divine judgment, resurrection, and the ultimate vindication of the righteous, along with a heavily dualistic worldview.4 Such literature also introduces the notion of heavenly tablets or books recording human deeds—concepts that would later be adapted in early Christian eschatology. These ideas suggest a deterministic view of history, where God’s hidden plan is progressively revealed through visions and intermediaries, such as angels. By depicting a heavenly realm with its own order and narrative, Jewish apocalyptic texts offered assurance to suffering communities that God’s justice extended beyond earthly chronology and would eventually manifest through cosmic transformation.5

The late Second Temple period also saw the rise of sectarian groups—such as the Essenes and the Qumran community—whose writings at the Dead Sea further illuminate Jewish apocalyptic expectations. The War Scroll (1QM), found among the Dead Sea Scrolls, outlines a detailed eschatological battle between the “Sons of Light” and the “Sons of Darkness.”6 The community viewed itself as the elect remnant, called to preserve divine law in anticipation of God’s imminent judgment on a corrupt world. Their writings emphasize predestination, angelology, and a messianic hope that likely included two messianic figures: a priestly and a royal messiah.7 This dual messianism and their anticipation of a final battle would influence early Christian understandings of Christ’s identity and role, especially as a spiritual and political liberator. The continuity between these Jewish sectarian texts and early Christian writings reveals not only thematic similarities but also a shared apocalyptic consciousness rooted in resistance to imperial domination and religious corruption.

Jewish apocalypticism laid the theological, literary, and symbolic groundwork for Christian eschatological thought. The early Jesus movement, which emerged within this richly apocalyptic milieu, adapted these motifs to its own convictions regarding the death and resurrection of Jesus as the climactic event in salvation history. Jesus’ frequent use of Danielic language—particularly in his references to the “Son of Man coming on the clouds”—demonstrates this continuity.8 Paul’s epistles and the Book of Revelation continue this tradition, interpreting Jesus’ messiahship as both fulfillment and intensification of Jewish apocalyptic hopes. What began as a distinctly Jewish form of resistance literature evolved, in the Christian context, into a broader cosmic theology centered on the figure of Christ. Nevertheless, Christian apocalypticism remained deeply indebted to its Jewish roots in both form and content, preserving the conviction that divine justice would decisively reorder history in favor of the faithful.

Apocalypticism in Early Christianity

The earliest layers of Christian tradition are deeply steeped in apocalyptic expectation, a fact that is evident in both the sayings attributed to Jesus and the writings of the first Christian communities. Apocalyptic themes dominate the Synoptic Gospels, particularly in passages such as the so-called “Little Apocalypse” (Mark 13; Matthew 24; Luke 21), in which Jesus foretells cosmic upheaval, persecution, and the coming of the Son of Man. These discourses echo the imagery of Daniel and other Second Temple Jewish texts, revealing how early Christians understood their present trials within a larger eschatological framework. Jesus’ message that “this generation will not pass away until all these things have taken place” (Mark 13:30) illustrates the imminence of the expected end and God’s intervention.9 While interpretations of this passage vary, many scholars argue that Jesus himself, or at least the earliest Jesus followers, expected a radical transformation of history within their own lifetime.10 This sense of temporal urgency and divine judgment marked the foundation of early Christian apocalyptic consciousness.

Paul’s letters—the earliest surviving Christian texts—reveal a similar apocalyptic outlook. In his first epistle to the Thessalonians, Paul comforts believers with the assurance that “the Lord himself will descend from heaven… and the dead in Christ will rise first” (1 Thess. 4:16).11 Paul’s theology hinges on the idea of an imminent parousia (return of Christ), which would inaugurate the resurrection of the dead and the final vindication of the faithful. His writings also introduce the idea of being “in Christ” as a kind of eschatological state, where believers already participate in the new age even as they await its consummation. Though Paul would later moderate some of his earlier urgency in letters like Romans and Philippians, his conviction that the present age was giving way to the kingdom of God remained a central tenet.12 For Paul, the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus were not just redemptive acts but apocalyptic events that initiated the long-awaited reversal of cosmic and moral disorder foretold in Jewish apocalyptic literature.

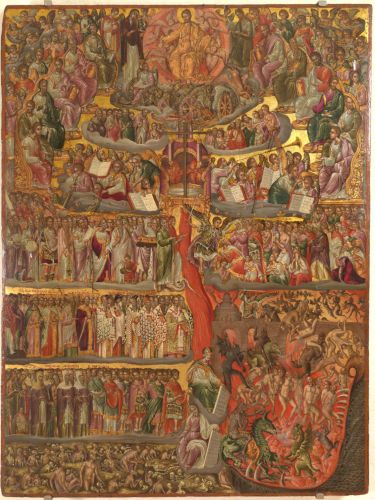

The Book of Revelation, or the Apocalypse of John, is the most overtly apocalyptic text in the Christian canon and provides a symbolic and theological climax to early Christian eschatology. Written near the end of the first century CE, likely during the reign of Domitian, Revelation reflects the social and political tensions faced by Christians under Roman rule.13 Employing vivid and often violent imagery, the text portrays a cosmic battle between good and evil, culminating in the destruction of Babylon (a coded reference to Rome), the final judgment, and the establishment of a New Heaven and New Earth. Revelation is deeply indebted to earlier Jewish apocalyptic works, especially Daniel, Ezekiel, and 1 Enoch, but it recasts their themes in a distinctively Christian mold—identifying Jesus as the sacrificial Lamb who is also the triumphant warrior.14 The work’s symbolic complexity and densely woven typology demonstrate the evolution of apocalypticism into a rich literary-theological form within early Christianity, capable of addressing both spiritual and political crises.

Apocalypticism also influenced Christian ethics and community structure in the early Church. Believing that the end was near, many early Christians adopted radical stances toward wealth, family, and social status. The Acts of the Apostles reports communal sharing of property, which many interpret as an expression of eschatological urgency and detachment from worldly possessions (Acts 2:44–45). Likewise, Paul counseled believers to remain in whatever state they were called—married or unmarried—because “the appointed time has grown short” (1 Cor. 7:29).15 This perspective shaped early Christian attitudes toward celibacy, martyrdom, and nonviolence, emphasizing fidelity and endurance in the face of suffering. Even as the Church institutionalized and expanded beyond its apocalyptic roots, these early values continued to inform monasticism, liturgy, and Christian hope, revealing how deeply the eschatological imagination had shaped Christian identity and moral life from the outset.16

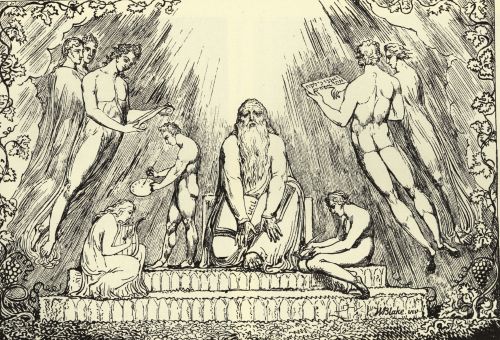

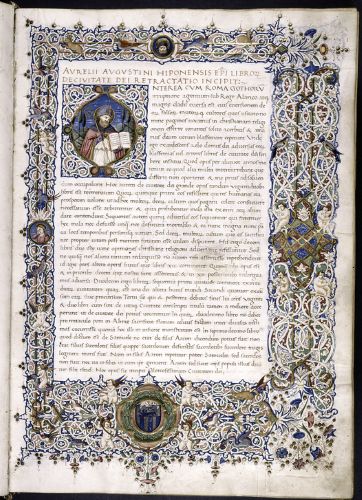

Despite the eventual delay of the parousia and the Church’s growing accommodation to the Roman world, apocalypticism never disappeared from Christian thought. Instead, it was spiritualized and reinterpreted. Augustine, for instance, in The City of God, argued that the true kingdom of God was not a temporal political event but a transcendent reality unfolding through the Church.17 Yet even in this transformed state, the apocalyptic imagination persisted—later fueling millenarian movements in medieval Christianity, Reformation-era eschatology, and modern fundamentalist thought. Early Christianity’s apocalypticism, then, was not a fringe phenomenon but a core expression of its theological, moral, and political self-understanding. It provided a language of hope and resistance, situating the crucified Messiah at the center of history’s cosmic drama. The expectation that history is moving toward divine judgment and renewal remains one of Christianity’s most enduring legacies, rooted deeply in its apocalyptic beginnings.

Medieval Christian Apocalypticism

Medieval Christian apocalypticism built upon the foundations laid in the early Church, evolving in response to new political, social, and religious dynamics. With the decline of the Roman Empire and the establishment of Christendom in Western Europe, Christian thinkers reinterpreted apocalyptic symbols to reflect the realities of their time. Saint Augustine’s reinterpretation of apocalyptic expectation had a profound impact. In The City of God, Augustine downplayed the idea of a literal and imminent end of the world and instead spiritualized the apocalyptic narrative, seeing the “City of God” as unfolding throughout history in the form of the Church.18 This theological pivot allowed apocalypticism to persist in a less urgent but still influential form. The idea of the Church as the present but imperfect manifestation of divine rule created space for a long view of salvation history, punctuated by moments of crisis, judgment, and renewal.

Despite Augustine’s moderating influence, popular apocalyptic fervor often surged in the face of instability, such as during the approach of the first millennium. The so-called “Millennium Fever” around the year 1000 CE, although likely exaggerated in modern historiography, reflects a recurring theme in medieval thought: the fear that widespread sin and corruption would provoke divine retribution.19 Chroniclers like Rodulfus Glaber and others recorded signs and wonders interpreted as omens of the End Times, linking them to apocalyptic texts like the Book of Revelation and Daniel.20 These expectations were amplified by social dislocation, famine, and war, which seemed to confirm prophecies of tribulation preceding the Second Coming. Importantly, these were not only elite anxieties but were shared widely among the laity, whose imagination was nourished by sermons, art, and religious festivals steeped in eschatological imagery.

One of the most influential figures in shaping medieval apocalypticism was Joachim of Fiore (c. 1135–1202), a Cistercian monk and mystic whose elaborate trinitarian theory of history had a profound impact on both orthodox and heterodox thought. Joachim proposed a threefold historical schema: the Age of the Father (Old Testament), the Age of the Son (New Testament Church), and the impending Age of the Spirit, a time of spiritual renewal and freedom that would transcend clerical authority.21 His exegesis of Revelation and other biblical texts was intensely symbolic and layered with numerical significance. While Joachim never directly challenged Church doctrine, his writings inspired numerous radical groups in later centuries, such as the Spiritual Franciscans, who believed themselves to be harbingers of the final age.22 The Church would eventually condemn many of these Joachite interpretations as heretical, yet his influence persisted in apocalyptic movements for generations.

The Crusades, particularly the First and Second Crusades, were also steeped in apocalyptic ideology. The call to liberate Jerusalem from Muslim control was often cast in eschatological terms, framing the conflict as a prelude to the return of Christ. Crusade sermons and literature employed imagery of Revelation, portraying Saracens as agents of the Antichrist or Gog and Magog, enemies of the faithful whose defeat was necessary for the restoration of the Holy City and the coming of the New Jerusalem.23 Figures like Bernard of Clairvaux saw the Crusades not just as military campaigns but as a spiritual war against the forces of darkness.24 These associations were particularly vivid after the failure of the Second Crusade, when setbacks were interpreted as divine punishment for sin, echoing the prophetic tradition of warning and chastisement found in earlier biblical and apocalyptic writings.

Later in the Middle Ages, apocalypticism became intertwined with reform movements, heresies, and even proto-revolutionary ideologies. The Black Death (1347–1351) reignited apocalyptic fears on an unprecedented scale. With up to half of Europe’s population dead, many interpreted the plague as a sign of divine wrath and a harbinger of the Last Judgment.25 Preachers and visionaries reported revelations of doom, and flagellant movements arose, promoting repentance and purification to avert further judgment. Meanwhile, figures like John Wycliffe and later Jan Hus linked ecclesiastical corruption with apocalyptic prophecy, casting the institutional Church as Babylon or the Whore of Revelation.26 By the late medieval period, apocalypticism had become a powerful tool for both spiritual reflection and social critique, serving as a lens through which believers made sense of historical calamity, institutional decay, and the longing for cosmic justice.

The Reformation and Early Modern Christian Apocalypticism

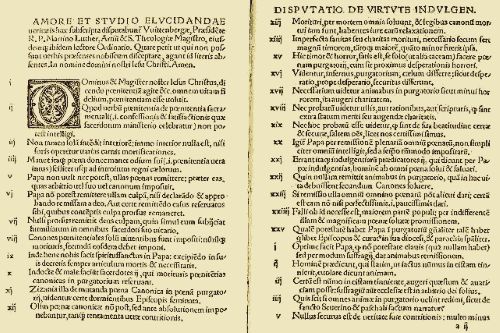

The Protestant Reformation marked a seismic shift not only in theology and ecclesiology but also in the development of Christian apocalyptic thought. Reformers such as Martin Luther and John Calvin inherited medieval eschatological traditions but reinterpreted them through the lens of their struggles against the Catholic Church. Luther, for instance, came to view the Papacy itself as the institution of the Antichrist.27 In his Smalkald Articles and other polemical writings, Luther interpreted Revelation not as a distant prophecy but as a living critique of his contemporary religious system, identifying the corruption of the Church with the Whore of Babylon.28 This eschatological framing gave the Reformation a heightened sense of urgency and cosmic importance. Apocalyptic imagery was used not just to interpret history but to motivate reform, embolden the faithful, and delegitimize Rome’s authority.

John Calvin was more restrained in his use of apocalyptic language than Luther, but he too contributed to a growing Protestant apocalypticism. Calvin focused less on the identification of historical actors with apocalyptic figures and more on the ethical and spiritual implications of divine judgment.29 Nevertheless, the spread of Calvinist thought in places like Geneva, Scotland, and the Netherlands accompanied the rise of millenarian expectations, especially during periods of persecution. Early Protestant exegesis often viewed history as a succession of epochs or dispensations that culminated in a final, purifying confrontation between the true Church and its persecutors.30 These interpretations were not just academic—they were preached from pulpits and disseminated through widely printed pamphlets and broadsides, democratizing apocalyptic ideas among a growing literate population.

The invention of the printing press dramatically accelerated the dissemination of apocalyptic texts and interpretations during the early modern period. Works like the Geneva Bible, with its extensive marginal notes, offered readers a distinctly Protestant framework for understanding prophecy.31 Apocalypticism also manifested in visual culture: woodcuts, engravings, and broadsheets depicted the Beast, the Whore of Babylon, and the heavenly Jerusalem, often with thinly veiled references to contemporary political and religious figures.32 This popular apocalypticism helped fuel social unrest, such as the Peasants’ War in Germany (1524–25), where some participants interpreted their revolt as a fulfillment of divine prophecy.33 The link between apocalyptic expectation and revolutionary impulse became increasingly common, particularly among radical reformers and sectarian groups who believed themselves to be the vanguard of God’s final kingdom.

Perhaps the most dramatic expression of apocalypticism during the Reformation was found in radical sects like the Anabaptists and the followers of Thomas Müntzer. Müntzer, unlike Luther, embraced a militant eschatology. He called for the violent overthrow of the godless order to usher in God’s kingdom on earth.34 His involvement in the Peasants’ War and his death at the hands of princely forces turned him into a martyr for later revolutionary movements. Meanwhile, the Anabaptist takeover of Münster in 1534–35 saw a bizarre and violent attempt to establish a New Jerusalem, replete with prophetic leaders, polygamy, and apocalyptic warfare.35 Though crushed, the Münster Rebellion lingered in European memory as a terrifying example of how apocalyptic fervor could turn into theocratic tyranny. These events underscored the capacity of apocalyptic ideas to both inspire utopian visions and incite chaos.

In England and the broader Anglophone world, apocalypticism remained potent well into the seventeenth century, particularly during the English Civil War and Interregnum. Figures like John Foxe, in his Acts and Monuments, presented a vision of Protestant history framed by martyrdom and eschatological struggle.36 The Puritans, influenced by both Calvinist theology and Joachite prophecy, often viewed their cause as part of a cosmic battle against Antichristian tyranny.37 Apocalyptic rhetoric found its way into sermons, political tracts, and colonial visions—especially in New England, where settlers like John Winthrop imagined their new society as a “city upon a hill,” playing a pivotal role in the unfolding of God’s plan.38 The early modern period, then, was not a time of apocalyptic decline but transformation—where prophetic imagination adapted to the new realities of print, reform, and revolution, shaping political ideologies and national identities across Protestant Europe and beyond.

Modern and Contemporary Christian Apocalypticism

The Enlightenment and subsequent rise of rationalism and scientific empiricism during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries challenged traditional Christian eschatology, yet apocalypticism did not vanish—it evolved. While many theologians and philosophers sought to demythologize religious belief, others responded by reaffirming a literal reading of biblical prophecy. One of the most influential developments was the rise of dispensational premillennialism, a theological system popularized by John Nelson Darby in the 1830s.39 Darby, a key figure in the Plymouth Brethren movement, introduced a new framework for interpreting scripture that included a secret “rapture” of the Church before a period of tribulation and Christ’s millennial reign on earth.40 His ideas gained widespread traction in the United States through the Scofield Reference Bible, first published in 1909, which provided accessible and systematized notes alongside the biblical text.41 This approach to prophecy interpretation not only shaped American evangelicalism but also became foundational to much of modern Christian fundamentalism.

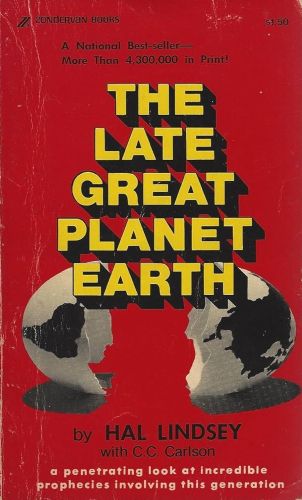

In the twentieth century, dispensationalist and apocalyptic themes permeated American religious life, especially during moments of global crisis. Events such as the World Wars, the Cold War, and later the Gulf War were interpreted by many evangelicals as signs of the end times.42 Apocalyptic rhetoric was not confined to pulpits but extended into popular culture, where prophecy conferences, radio broadcasts, and eventually television ministries reinforced the belief that the world was hurtling toward a divine climax.43 Figures like Hal Lindsey helped to popularize apocalypticism among a broader public through books like The Late Great Planet Earth (1970), which interpreted contemporary geopolitics—especially the formation of the state of Israel—as direct fulfillments of biblical prophecy.44 Lindsey’s work became one of the best-selling nonfiction books of the 1970s, illustrating the broad cultural appetite for eschatological narratives amidst political instability and nuclear anxiety.

The late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries saw Christian apocalypticism become a multimedia phenomenon, especially in the United States. The Left Behind series by Tim LaHaye and Jerry B. Jenkins, beginning in 1995, presented a dramatized fictional account of the rapture and the tribulation that followed.45 These books sold tens of millions of copies and spawned films, video games, and youth-targeted literature, embedding apocalyptic themes into the fabric of American evangelical subculture.46 At the same time, the rise of the Religious Right and its close alliance with conservative politics helped solidify a form of political apocalypticism, where domestic and foreign policies—particularly those related to Israel, abortion, and moral legislation—were viewed through the lens of spiritual warfare and eschatological necessity.47 This marriage of theology and politics continued to shape voter behavior and public discourse, especially in times of national trauma like 9/11, which was frequently framed in sermons and Christian media as a warning or judgment from God.

Apocalypticism has also been transfigured in the digital age, expanding beyond traditional religious institutions. Social media, YouTube, and podcast platforms have enabled independent preachers, conspiracy theorists, and charismatic influencers to spread end-times narratives with unprecedented speed and reach.48 Often blending biblical prophecy with political ideology and conspiratorial thinking, these messages have contributed to the spread of what scholars call “improvised eschatologies.”49 The COVID-19 pandemic, global climate change, and geopolitical tensions have only intensified the proliferation of these narratives, with many online communities interpreting events through the lens of Revelation or Daniel. Some fringe movements have even blended evangelical apocalypticism with elements of QAnon or other nationalist ideologies, forming a hybrid theology that is difficult to disentangle from broader sociopolitical unrest.50 In this way, contemporary apocalypticism often serves as both a religious worldview and a psychological coping mechanism in an era of global uncertainty.

Despite the dangers of extremist forms, Christian apocalypticism in the modern era is not uniformly destructive or reactionary. Progressive Christian movements have also reinterpreted apocalyptic themes, seeing in the Book of Revelation not a call to escape the world but a prophetic critique of empire and injustice.51 Liberation theologians and social justice advocates have pointed to Revelation’s imagery of Babylon and the New Jerusalem as metaphors for economic oppression and human flourishing, respectively.52 In this light, the apocalyptic is not the end but a radical unveiling of the world’s true moral condition and a call to transformative action. Thus, modern apocalypticism remains deeply ambivalent—capable of inspiring both fear and hope, sectarianism and solidarity. It persists not only because of its religious authority but because it continues to offer meaning in a rapidly changing and often destabilizing world.

Conclusion

Apocalypticism in Christian history is more than a fixation on doomsday scenarios; it is a dynamic and multifaceted tradition that has shaped theology, ethics, politics, and culture for two millennia. From its Jewish roots to its modern iterations, Christian apocalypticism has functioned both as a theology of hope and a critique of power. It has inspired both quietistic withdrawal and revolutionary action, both consolation and confrontation. Understanding this tradition provides not only insight into the past but a critical lens for interpreting the present. In a world beset by uncertainty, the apocalyptic imagination continues to challenge, comfort, and call communities to account.

Appendix

Endnotes

- John J. Collins, The Apocalyptic Imagination: An Introduction to Jewish Apocalyptic Literature, 3rd ed. (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2016), 1–25.

- Lester L. Grabbe, An Introduction to Second Temple Judaism: History and Religion of the Jews in the Time of Nehemiah, the Maccabees, Hillel and Jesus (London: T&T Clark, 2010), 125–128.

- Daniel 7:13–14, New Revised Standard Version.

- George W. E. Nickelsburg, 1 Enoch: A Commentary on the Book of 1 Enoch, Chapters 1–36; 81–108 (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2001), 1–10.

- Matthias Henze, Jewish Apocalypticism in Late First Century Israel: Reading Second Baruch in Context (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2011), 67–84.

- Florentino García Martínez and Eibert J.C. Tigchelaar, eds., The Dead Sea Scrolls Study Edition, vol. 1 (Leiden: Brill, 1997), 111–118.

- Gabriele Boccaccini, Roots of Rabbinic Judaism: An Intellectual History, from Ezekiel to Daniel (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2002), 179–182.

- N.T. Wright, Jesus and the Victory of God (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1996), 340–378.

- Mark 13:30, New Revised Standard Version.

- Dale C. Allison Jr., Jesus of Nazareth: Millenarian Prophet (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1998), 110–129.

- 1 Thessalonians 4:16, New Revised Standard Version.

- Paula Fredriksen, Paul: The Pagans’ Apostle (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017), 150–173.

- Adela Yarbro Collins, Crisis and Catharsis: The Power of the Apocalypse (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1984), 69–95.

- Richard Bauckham, The Theology of the Book of Revelation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 58–76.

- 1 Corinthians 7:29, New Revised Standard Version.

- Wayne A. Meeks, The First Urban Christians: The Social World of the Apostle Paul (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983), 139–145.

- Augustine, The City of God, trans. Henry Bettenson (London: Penguin Classics, 2003), Book XIX.

- Augustine, The City of God, Book XX.

- Richard Landes, Heaven on Earth: The Varieties of the Millennial Experience (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 69–94.

- Rodulfus Glaber, The Five Books of the Histories, trans. John France (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989), 45–58.

- Marjorie Reeves, The Influence of Prophecy in the Later Middle Ages: A Study in Joachimism (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969), 23–56.

- Bernard McGinn, Visions of the End: Apocalyptic Traditions in the Middle Ages (New York: Columbia University Press, 1979), 125–148.

- Jay Rubenstein, Armies of Heaven: The First Crusade and the Quest for Apocalypse (New York: Basic Books, 2011), 155–170.

- Bernard of Clairvaux, In Praise of the New Knighthood, trans. Conrad Greenia (Collegeville, MN: Cistercian Publications, 2000), 31–38.

- Norman Cohn, The Pursuit of the Millennium: Revolutionary Millenarians and Mystical Anarchists of the Middle Ages (New York: Oxford University Press, 1970), 92–110.

- Michael Frassetto, Heresy and the Politics of Community: The Jews of Medieval Normandy (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2001), 137–152.

- Martin Luther, The Smalkald Articles, trans. Charles M. Jacobs, in Luther’s Works, Vol. 2 (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1959), 289–312.

- Bernard McGinn, Antichrist: Two Thousand Years of the Human Fascination with Evil (San Francisco: Harper, 1994), 150–155.

- John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, trans. Henry Beveridge (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2008), IV.xix.

- Bauckham, The Theology of the Book of Revelation, 138-145.

- Christopher Hill, The English Bible and the Seventeenth-Century Revolution (London: Penguin, 1994), 41–58.

- Margaret Aston, Apocalypse and Reform from Late Antiquity to the Middle Ages (London: T&T Clark, 1990), 205–225.

- Cohn, The Pursuit of the Millennium, 187-202.

- Peter Blickle, The Revolution of 1525: The German Peasants’ War from a New Perspective, trans. Thomas A. Brady Jr. and H. C. Erik Midelfort (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1981), 103–118.

- R. Po-Chia Hsia, The German People and the Reformation (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1988), 134–149.

- John Foxe, Acts and Monuments of the Christian Martyrs (London: John Day, 1563; reprint, New York: AMS Press, 1965).

- William Haller, The Rise of Puritanism (New York: Columbia University Press, 1938), 215–240.

- Sacvan Bercovitch, The American Jeremiad (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1978), 7–19.

- Ernest R. Sandeen, The Roots of Fundamentalism: British and American Millenarianism, 1800–1930 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970), 63–78.

- John Nelson Darby, The Hopes of the Church of God (London: G. Morrish, 1840), 1–22.

- C. I. Scofield, ed., The Scofield Reference Bible (New York: Oxford University Press, 1909).

- Paul Boyer, When Time Shall Be No More: Prophecy Belief in Modern American Culture (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1992), 137–171.

- Susan Harding, The Book of Jerry Falwell: Fundamentalist Language and Politics (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000), 87–101.

- Hal Lindsey and Carole C. Carlson, The Late Great Planet Earth (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1970).

- Tim LaHaye and Jerry B. Jenkins, Left Behind: A Novel of the Earth’s Last Days (Wheaton: Tyndale House, 1995).

- Amy Johnson Frykholm, Rapture Culture: Left Behind in Evangelical America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 19–45.

- Matthew Avery Sutton, American Apocalypse: A History of Modern Evangelicalism (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014), 233–259.

- Christopher Partridge, The Re-Enchantment of the West, Vol. 2 (London: T&T Clark, 2005), 211–228.

- Michael Barkun, A Culture of Conspiracy: Apocalyptic Visions in Contemporary America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013), 87–102.

- Elizabeth Neumann, “Conspiracy Theories, QAnon, and Evangelicals: A Dangerous Mix,” Religion & Politics, March 3, 2021.

- Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza, Revelation: Vision of a Just World (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1991), 68–85.

- Miguel A. De La Torre, Reading the Bible from the Margins (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2002), 173–190.

Bibliography

- Allison, Dale C., Jr. Jesus of Nazareth: Millenarian Prophet. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1998.

- Aston, Margaret. Apocalypse and Reform from Late Antiquity to the Middle Ages. London: T&T Clark, 1990.

- Augustine. The City of God. Translated by Henry Bettenson. London: Penguin Classics, 2003.

- Barkun, Michael. A Culture of Conspiracy: Apocalyptic Visions in Contemporary America. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013.

- Bauckham, Richard. The Theology of the Book of Revelation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- Bercovitch, Sacvan. The American Jeremiad. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1978.

- Bernard of Clairvaux. In Praise of the New Knighthood. Translated by Conrad Greenia. Collegeville, MN: Cistercian Publications, 2000.

- Blickle, Peter. The Revolution of 1525: The German Peasants’ War from a New Perspective. Translated by Thomas A. Brady Jr. and H. C. Erik Midelfort. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1981.

- Boccaccini, Gabriele. Roots of Rabbinic Judaism: An Intellectual History, from Ezekiel to Daniel. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2002.

- Boyer, Paul. When Time Shall Be No More: Prophecy Belief in Modern American Culture. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1992.

- Calvin, John. Institutes of the Christian Religion. Translated by Henry Beveridge. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2008.

- Cohn, Norman. The Pursuit of the Millennium: Revolutionary Millenarians and Mystical Anarchists of the Middle Ages. New York: Oxford University Press, 1970.

- Collins, Adela Yarbro. Crisis and Catharsis: The Power of the Apocalypse. Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1984.

- Collins, John J. The Apocalyptic Imagination: An Introduction to Jewish Apocalyptic Literature. 3rd ed. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2016.

- Darby, John Nelson. The Hopes of the Church of God. London: G. Morrish, 1840.

- De La Torre, Miguel A. Reading the Bible from the Margins. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2002.

- Fiorenza, Elisabeth Schüssler. Revelation: Vision of a Just World. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1991.

- Foxe, John. Acts and Monuments of the Christian Martyrs. London: John Day, 1563. Reprint, New York: AMS Press, 1965.

- Frassetto, Michael. Heresy and the Politics of Community: The Jews of Medieval Normandy. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2001.

- Fredriksen, Paula. Paul: The Pagans’ Apostle. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017.

- Frykholm, Amy Johnson. Rapture Culture: Left Behind in Evangelical America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- García Martínez, Florentino, and Eibert J.C. Tigchelaar, eds. The Dead Sea Scrolls Study Edition. Vol. 1. Leiden: Brill, 1997.

- Glaber, Rodulfus. The Five Books of the Histories. Translated by John France. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989.

- Grabbe, Lester L. An Introduction to Second Temple Judaism: History and Religion of the Jews in the Time of Nehemiah, the Maccabees, Hillel and Jesus. London: T&T Clark, 2010.

- Haller, William. The Rise of Puritanism. New York: Columbia University Press, 1938.

- Harding, Susan. The Book of Jerry Falwell: Fundamentalist Language and Politics. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000.

- Henze, Matthias. Jewish Apocalypticism in Late First Century Israel: Reading Second Baruch in Context. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2011.

- Hill, Christopher. The English Bible and the Seventeenth-Century Revolution. London: Penguin, 1994.

- Hsia, R. Po-Chia. The German People and the Reformation. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1988.

- LaHaye, Tim, and Jerry B. Jenkins. Left Behind: A Novel of the Earth’s Last Days. Wheaton: Tyndale House, 1995.

- Landes, Richard. Heaven on Earth: The Varieties of the Millennial Experience. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Lindsey, Hal, and Carole C. Carlson. The Late Great Planet Earth. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1970.

- Luther, Martin. The Smalkald Articles. Translated by Charles M. Jacobs. In Luther’s Works, Vol. 2. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1959.

- McGinn, Bernard. Antichrist: Two Thousand Years of the Human Fascination with Evil. San Francisco: Harper, 1994.

- McGinn, Bernard. Visions of the End: Apocalyptic Traditions in the Middle Ages. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979.

- Meeks, Wayne A. The First Urban Christians: The Social World of the Apostle Paul. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983.

- Neumann, Elizabeth. “Conspiracy Theories, QAnon, and Evangelicals: A Dangerous Mix.” Religion & Politics. March 3, 2021.

- Nickelsburg, George W. E. 1 Enoch: A Commentary on the Book of 1 Enoch, Chapters 1–36; 81–108. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2001.

- Partridge, Christopher. The Re-Enchantment of the West, Vol. 2. London: T&T Clark, 2005.

- Reeves, Marjorie. The Influence of Prophecy in the Later Middle Ages: A Study in Joachimism. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969.

- Rubenstein, Jay. Armies of Heaven: The First Crusade and the Quest for Apocalypse. New York: Basic Books, 2011.

- Sandeen, Ernest R. The Roots of Fundamentalism: British and American Millenarianism, 1800–1930. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970.

- Scofield, C. I., ed. The Scofield Reference Bible. New York: Oxford University Press, 1909.

- Sutton, Matthew Avery. American Apocalypse: A History of Modern Evangelicalism. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014.

- Wright, N.T. Jesus and the Victory of God. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1996.

Originally published by Brewminate, 06.06.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.