One of the most serious problems of emerging nations is the handling of competing interests.

By Dr. Alison G. Olson

Professor Emerita of History

University of Maryland

The history of the eighteenth-century English Board of Trade has hardly been regarded as a success story by the historians who have written it. Created in 1696 to make recommendations on questions of imperial administration, nominate colonial officials to carry out their recommendations, and back up the provincial officials in office, the Board is commonly agreed to have failed at all its jobs. Either (by one set of accounts) power-hungry ministers did it in by overriding or ignoring its recommendations, stripping it of its important nominations, and appointing second-raters to the Board itself or (by another set of accounts) the Board’s heavy-handed mercantile approach and indolence in backing up the officials charged with implementing it brought on it the hostility of colonists and royal officials alike. In either case the question seems not to have been whether the Board failed, but why.1

Recent studies of administration in developing countries (as Great Britain certainly was in the eighteenth century) suggest that it might be time for at least a partial rehabilitation of the Board’s reputation. They suggest, by comparison, that the Board was performing a function that has hitherto been little emphasized, namely the accommodation of various pre-modern and modern interest groups that were emerging in eighteenth-century England.

The Board’s establishment coincided in time with a period of rapid proliferation of London interest groups with American connections. There were three main types of these London-American groups, mercantile, ethnic, and ecclesiastic, each with its own political leverage, and since the Board was to specialize in mercantile and imperial problems the work of accommodating these London-American groups fell heavily upon it. In handling its work the Board sought their advice, often acceded to their demands, and built up a comfortable working relationship with each of them.

One of the most serious problems of emerging nations is the handling of competing interests; domestic political stability depends upon their doing so effectively.2 By the standards of developing nations Britain was remarkably successful in accommodating interest groups in the early eighteenth century, and the Board of Trade appears to have contributed substantially to its success. The years of greatest British success, 1700 to 1760, coincided with the period of the Board’s greatest activity. In the later eighteenth century after 1760, British success was considerably more limited and interest groups became increasingly dissatisfied with the status quo. This period, in turn, was coincident with a period of declining activity and influence for the Board of Trade.

Such an interpretation must begin with a definition of ‘interest group’. Eighteenth-century writers like Edmund Burke identified increasingly differentiated interests within the governing community-a landed interest, a mercantile interest, a professional interest, and so on. But such broad, ‘fixed’ categories bore little relation either to the way men acted or to the kinds of groups that lobbied at various levels of government. Recent writers have laid more stress on interest groups functioning outside the centres of political power but have not developed a commonly accepted definition. Recognising, therefore, that any definition will be arbitrary, we may suggest ‘a group that accepts the political system and attempts through bargaining with political authorities to improve its own position in it, operating from the borders of power, influencing but not directly making political decisions.’ By this definition there were few transatlantic interests in existence before the Board’s establishment in 1696: towns, guilds and chartered commercial companies had all functioned as interests in England but none (including the Hudson’s Bay Company and the Royal African Company, surprisingly) was to develop American associations.3 Among the groups that did come to be ‘Anglo-American’ as opposed to ‘Anglo’, a few dated back to the 1670s but in that early decade they lacked either American connections or an efficient lobbying organisation, or both. The Quaker Yearly Meeting, established in 1675, had by 1678 appointed a clerk to take down the heads of bills which might affect Quakers. Evidently the custom soon fell into abeyance, though after the settlement of Pennsylvania the meeting began regular correspondence with the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting on political as well as theological questions.4 The Bishop of London had been given the administration of the Anglican church in the colonies in 1675, and began taking a fuller interest in them after 1689 when James Blair went to Virginia as the Bishop’s first commissary, authorised to convene the local clergy and send back reports of their local grievances to the Bishop.5 But by the early 1690s Virginia represented the only colony to have such relations with the Anglican church in England. General Baptists began meeting regularly after 1686 but by the early 1690s had not yet concerned themselves with American issues.6 In the thirty-six years between the restoration of Charles II in 1660 and the Board’s establishment in 1696, the Privy Council had received petitions from three interest groups; between 1686 and 1696 the old Lords of Trade, predecessors of the Board of Trade, had received four petitions from what might be called English interest groups, but two were from the would-be organisers of companies that never formed and one was from the proprietors of New Jersey.7 Indeed, by the time the Board was created only two groups, the French Committee of London, set up to aid Huguenot refugees (and on occasion to help them get to America), and the London merchants trading to Virginia, could truly be said to constitute organised Anglo-American interests.8

Within a few years of the Board’s establishment, however, this was no longer true. By 1701 the Quakers had established a committee to lobby members of Parliament, and by 1704 the London Meeting for Sufferings had begun corresponding regularly with yearly meetings in New England and the southern colonies as well as Philadelphia.9 After 1701 the Anglican church began sending commissaries to every colony; and it also established the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel to work with Anglican communities overseas, mainly in the northern mainland colonies10 The same year the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge was established, developing continental connections which led them to focus their attention on helping non-English communities in America.11 In 1702, also, after a false start ten years earlier, ministers of the Three Denominations in London (Baptist, Presbyterian, Congregational) began meeting; in their first few years they did little but present formal addresses to the king but by 17 I 5 they were intermittently becoming more active.12 In 1706 American Presbyterians established a Presbytery in Pennsylvania and began corresponding with English Presbyterians as well as the General Assembly of Scotland.13 Again in 1702, the Sephardic Jewish congregation at Bevis Marks established a Committee of Deputies to ‘attend to the business of the nation which is before Parliament’.14 The Huguenot Society, with connections in the Threadneedle Street Church, initiated its correspondence with American churches between 1699 and 1702;15 the Lutherans were slow to organise as an interest but the first Lutheran chaplain was appointed to the royal chapel early in Queen Anne’s reign, establishing political influence for the Lutheran communities at court.16 Finally, our first record of three mercantile coffee houses, the Pennsylvania, New England, and Carolina coffee houses, dates from 1702, and the New York Coffee House was probably established shortly before this.17 By 1706 English coffee house leaders were in informal correspondence with merchant groups in Charleston, Philadelphia, New York City, and Boston. The cumulative growth of Anglo-American interests is suggested by the fact that the Board received fifty-one petitions from such groups before 1709.

Though the actual circumstances surrounding the development of different groups varied, there were at least two general explanations for the development of Anglo-American interests. One was the rapid growth of London towards the end of the seventeenth century.18 Interest groups, before 1760, at least, represented local interests, not national ones. But Londoners soon demonstrated a remarkable (by eighteenth-century standards) ability to speak for men of similar interests in provinces of England and the empire. The London Meeting for Sufferings, the Dissenting Deputies in and about London, the organisation of French churches in London, the Bevis Marks Committee, the network of Lutheran chaplains around the court and the SPCK, were composed of Londoners, but their role as spokesmen for the interests of all their co-religionists was rarely challenged by local associations. Similarly the London merchants, though at times competitors with the outport merchants, were with few exceptions their spokesmen in national politics, at least on American issues. It is significant here that London merchants could speak for Charleston merchants in much the same way that they spoke for merchants in Bristol and Norwich; London church lobbyists could speak for New York or Philadelphia church groups in the same way they spoke for church groups in the English provinces. The absence of national interests and the predominance of London over provincial interests in England and America allowed the Americans to fit easily into the pattern of English lobbying.19

Part of the importance of London lay simply in its proximity to the machinery of government. Londoners could respond more quickly than provincials to legislative or administrative threats, and they could be called upon more quickly for consultation. Part lay in the fact that Londoners developed a genuine acceptance of a pluralistic society long before the more homogeneous ‘island communities’ of the provinces were able to do so.20 But the largest part came from sheer numbers: interest groups in London were more likely than those in the provinces to have the numbers and wealth sufficient to produce surplus resources which could be used to help colleagues elsewhere. Rapid growth was not always an asset: the influx of thousands of French refugees into London after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 (eighteen French churches were established in the 1690s alone) greatly complicated the work of the Huguenot committee,21 and the influx of hundreds of Axkenzim Jews into an area of a few blocks in London in the same decade presented an enormous challenge to the leadership of the existing Sephardic community.22 But at the worst, a rapid growth in numbers could force a community to tighten its organisation to distribute evenly the available resources, and at best, when newcomers were assimilated and employed, large communities could tap resources beyond the immediate needs of their members. London’s congregations and non-English com-munities supplied their provincial colleagues with bibles, books, even ministers; London’s ethnic, ecclesiastical, and mercantile groups could use their surplus towards lobbying, supporting political agents, entertainment for politicians, legal fees, carriage fare, and the like.

A more general reason for the emergence of interests was the establishment of the eighteenth-century ‘political nation’ if, again being arbitrary, we define ‘political nation’ as the elite who governed England in the aftermath of the Glorious Revolution. For an interest group to operate from the ‘borders of power’ those borders must be defined, and it was in the reigns of William III and Anne that such a definition became possible (for England, though not for America). By Anne’s death, or at least shortly afterwards, it is arguable, some people were clearly ‘in’ the political nation, others were quite clearly out, and others-members of political interest groups-were in a stable position on the borders. Dissenters were left on the borders of the political nation by the combination of the failure of ecclesiastical comprehension and the passage of the Toleration Act in 1689, a pair of events which defined dissenters out of the established church, and hence largely out of the political nation, but established their right to existence on the fringes of that nation.23 Immigrants were left on the borders by a combination of a parliamentary act of 1712, which repealed a general Naturalization Act passed three years before, and the fact that they could obtain denisation from the King or Parliament, which allowed them to own land but not to participate actively in politics.24 Lesser merchants were left out of the financial nation by a combination of two things, the establishment of the national debt in 1696 (they could not subscribe) and the creation of London’s financial directorate (the Bank, the Royal Assurance Company, the East India Company, and a number of other large mercantile companies either were created or consolidated their power in William’s reign, and the lesser merchants were excluded from the directorships). They too, were on the fringes of power.25

The defining of the English political borders meant that interests no longer had hopes (as they had had from time to time in the Restoration) of being at the centre of power, but they also had no fears of being driven underground. No longer need they alternate, as the few existing Restoration interests had done, between wooing highly placed individuals in government and defensively protecting their people from these individuals by creating a state within a state. With a clearly defined position the London interests could devote themselves to systematic lobbying, helping colonial interests whose positions in the provinces were less weU defined.26

In the same period interest groups were developing in the American colonies. The growth of colonial stability in contrast with the violent challenges to colonial leadership in the 1670s and 1680s created an environment in which interest groups could also develop, though their position was often far less clear than the position of their English counterparts. Immigration from England and the continent and the commercial growth of the colonies produced concentrations of colonists with similar interests though except for the merchant communities these were as likely to be island communities outside the provincial capital as neighbourhoods within it, since the capitals were too small to develop the concentrations found in London.

American interests were more vulnerable to local pressures and less capable of developing surplus resources than the interest groups in the imperial capital They were also, in the last decade of the seventeenth century, far more directly affected by decisions made in London than they had been at any time earlier. After the Glorious Revolution five colonies came newly under temporary or permanent royal control which meant among other things that their governors were royal appointees guided by instructions prepared in London. Moreover, between 1685 and 1696 all the mainland colonies that had not previously done so were henceforth required to send their laws to England for review.27 Aware for the first time of the uses of London politics, American interest groups turned to London interests to assist them in local politics. Religious groups sought the disallowance of provincial laws discriminating against them and the appointment of sympathetic colonial officials. Ethnic groups were more interested in getting good community land, exemption from provincial taxes, and easy naturalization. Individually colonial planters and merchants sought the London merchants’ help in obtaining patronage and the approval of private provincial acts; as groups they were interested in getting British support for things like building lighthouses or opening up continental trade, favourable British review of some paper money issues, and the disallowance of provincial tax laws that discriminated against their mercantile or agricultural interests.28

The Americans solicited English help rather hesitantly at first, uncertain whether British interests would take colonial problems up as their own, uncertain also whether the cost-both in terms of money and in terms of the local stigma attached to appealing over the head of the provincial majority to an external authority–was worth it. They worked also by trial and error, on occasion sending laws too late for review, on other occasions sending laws that had expired or writing of rumoured laws that were never on the books.29 Nevertheless, after a shaky start the London-American connections developed rapidly in the two decades after the Glorious Revolution: London mercantile leaders sought political favours for their leading American correspondents to keep them happy, London church groups spread the faith by helping co-religionists in America, and non-English communities in London became convinced that the best way to prevent the periodic over-taxing of their resources by inundations of unassimilated poor was to help fellow refugees settle directly in America. At least fourteen American interests, including Quakers in three colonies, Anglicans in two others, ethnic minorities in four provinces and merchant groups in three cities, sought help from their English counterparts in bringing matters before the British government in this period. Thus the Board was established in the very period that saw the rapid development of London-American interest cooperation.

The Board’s duties were loosely defined-‘to inspect and examine into the general Trade of our said Kingdom and the several parts thereof’, ‘to consider of some proper methods for setting on worke and employing the Poore of our said Kingdome’, and ‘to inform yourselves of the present condition of the respective plantations’.30 With these functions, especially the last, the Board might have come to work with interests on any number of issues. But it came in practice to have four particular functions which were useful to the North American lobbies.

One such function was arranging the resettlement of non-English groups moving, sometimes via London, to America: the Board’s negotiations with ship captains for reasonable transportation across the Atlantic and with governors and assemblies for assistance to refugees once they arrived were of vital concern to non-English communities in London. Another function was the nomination of members of the colonial councils, a subject of particular interest to members of the London mercantile communities who sought nominations as favours to colonial correspondents as a way of establishing the trust on which their pre-modern mercantile relationship depended.

Far more important to most trans-Atlantic groups were two other functions. One was the drafting of instructions for colonial governors. Occasionally the great officers of state would interpose and alter gubernatorial instructions in response to English pressure. After a request from Benjamin Avery, head of the Protestant Dissenting Deputies, the Duke of Newcastle looked into the ‘instructions sent to Governor Shirley [of Massachusetts] and the difficulties which it is apprehended, they will occasion both to his Excellency and the province’.31 But most of the instructions were drawn up by the Board of Trade, and these occasionally included specific instructions for the enactment of provincial laws.

As the second of its more important functions, the Board was empowered ‘to examine into and weigh such Acts of the Assemblies of the Plantations respectively as shall from time to time be sent or transmitted hither for our approbation’ and ‘to set down and represent as aforesaid the usefulness or mischief thereof to our Crown, and to our said Kingdom of England or to the Plantations themselves in case the same should be established for Lawes there’. (Officially the Board’s function was only advisory, but the Privy Council normally followed its recommendation.) One of the principles behind the examination of provincial legislation was that, as stipulated in the various provincial charters, colonial laws could not be repugnant to the laws of England. This examination thus became in effect an antecedent of the modern judicial review, and the fact that it was handled in its early stages by the Board gave English interests a chance to work there to obtain the allowance or disallowance of laws affecting their American associates.

The Board’s main functions, then, were those of particular concern to the Anglo-American interests, and in handling the issues the Board was particularly responsive to their pressure. Since they often had a near monopoly of first-hand information on particular conditions in the colonies the Board sought them out when preparing its reports. When the Board wanted information about French Protestants who had landed at Jersey on their way to America, it consulted French ministers in London;32 when it wanted information about the working of South Carolina’s township law over the 1730s it consulted merchants trading to the colony;33 when it wanted to know to know how Connecticut’s ecclesiastical establishment was treating Quakers in 1705 it consulted two delegates from the London Meeting for Sufferings.34

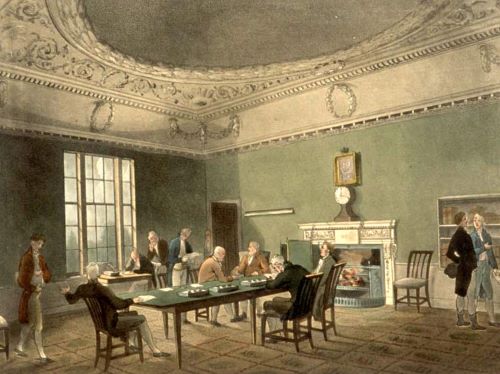

The Board sought more than information from the various interests; it sought the opinions of rank and file members on various questions. At times it sent someone out to poll them: leading merchants, colonial agents, or agents hired by the merchants themselves were asked to solicit the opinions of merchants as a group on questions like the placing of lighthouses or the timing of convoys.35 Twice a week its meetings were opened to the public and agents were sent to provide the interest groups in advance with notices of hearings the rank and file might usefully attend.36 Just how many people could squeeze in at any one meeting is not clear but in 171 I the active members of the Virginia ‘Trade’ decided to attend en masse, and though there were up to 175 of them, they anticipated no trouble getting in.37

There is also evidence that individual members of the Board consulted privately with interests on particular affairs: it would be surprising, in fact, if they had not. Members of the Board tended to be country gentlemen with little personal identification with any Anglo-American interest except the Anglican church.38 (The Bishop of London was an ex-officio member of the Board but he attended only six meetings in the eighteenth century, and while leaders of various interests, like the merchant William Baker39 were occasionally considered for seats at the Board, the appointments never materialised.) Nevertheless, particular members did develop connections with particular interest groups-Martin Bladen with the Chesapeake merchants in the 1740s, for example.40 James Oswald with Glasgow tobacco merchants the following decade,41 Viscount Dupplin with the Dissenters in the same period42-and these men served as informal channels between the interests and the Board.

The Board thus made a point of consulting with interest groups; it also tended to follow their recommendations. In handling non-English migration to the colonies it followed closely the advice of non-English communities in London, working with them to arrange the departure of emigres from Europe, to regulate the living conditions aboard the ships on which they sailed, to instruct the governors to provide them tax free land for a decade after their arrival in the colonies, and to oversee their supplies for some times after they settled. On the nomination to colonial councillorships it is difficult to be sure how influential the merchants were, since merchants passed their nominations on through individual members of the Board (i.e. ‘Buchanan pr. Col Bladen’)43 and the names of the merchants are not usually mentioned directly in the surviving lists of councillors and the men who nominated them. Probably merchant nominations accounted indirectly for 10-20 percent of colonial councillorships (the Bishop of London accounted for another 5 percent). This did not seem a small percentage to contemporaries: governors, who thought such nominations essential to the power of the governorship, were outraged by it.

It was in handling its two most important functions, however, the preparation of gubernatorial instructions and the review of provincial legislation, that the Board was most responsive to pressures from interest groups. Gubernatorial instructions were on occasion prepared explicitly to benefit particular interests. The Bishop of London helped to draft a Maryland act of 1700 establishing the Anglican church in that colony. The act was drawn up in London and transmitted to Maryland through the Governor’s instructions.44 Quaker pressure was responsible for Governor Hunter’s instruction in 1709: ‘You take care than an Act be passt in the General Assembly of your said Province to the like effect as that past here in the 7th and 8th years of his late Majesties reign Entituled an act that the Solemn affirmation and declaration of the People called Quakers shall be accepted instead of an Oath in the usual form’.45 A 1734 instruction to Governor Gooch of Virginia directed him to get a law passed to exempt German settlers from payment of parish taxes for a longer time than stipulated by previous law; the source of pressure for this instruction is clear enough.46 An instruction to South Carolina’s Governor regarding the setting aside money to create townships was in response to a representation from ‘planters and merchants trading to South Carolina’ 47 It is difficult, in fact, to find examples of instructions requested by ethnic and religious groups being turned down, and there were only a few such cases regarding the merchants.

Área de University of Wisconsin-Madison, Wikimedia CommonsThe function on which the Board was most responsive to interest group pressure was the review of colonial legislation, partly because interest groups often had first-hand information about a particular law’s ‘usefulness or mischief’ to a province, partly because most English laws were unclear when applied to a colonial situation. The Board could develop few principles and was forced instead to make a series of ad hoc decisions, for each of which it relied on information from English interests about the way in which their American correspondents would be affected. The English Toleration Act, for example, was one of those acts to which colonial acts were supposed to conform: it exempted Dissenters from the legal penalties which the Test and Corporation Acts imposed upon them. But how did the law apply when a Dissenting church was actually the established church in a province? In colonies where the Church of England was ‘tolerated’ but not established, did toleration extend to Bishops? Faced with these and innumerable other questions about the Toleration Act, the Board interpreted the act differently from colony to colony, on various occasions consulting the Bishop of London and representatives of Dissenting interests. Similarly, colonial laws were to conform to the Navigation Acts and were not to prejudice the trade of the mother country. But what taxes could colonial assemblies levy without in some way prejudicing the trade of the mother country? Governor Hunter of New York complained that ‘by clamours of merchants or those self-interested, every sort of duty many be construed to affect the trade of Great Britain.’48 Faced again with difficult interpretations, the Board turned to London merchants and agents of the colonial assemblies for advice.

Thus the Board became extremely responsive to interests in the matter of legislative review. The Board’s records mention specifically only two cases where non-English representatives were consulted on particular provincial legislation,49 but it is difficult to find any provincial acts reviewed otherwise than non-English groups would have wanted. Governor Spotswood referred to the Board’s deference to merchants in 1718 when he complained that the London merchants trading to Virginia might as well draw up their own version of a tobacco inspection act to be passed in the colony, ‘otherwise there is no pleasing them’.50 The governor’s complaint was fair enough: the only occasions on which the merchants’ views were disregarded were rare ones on which they were clearly ill informed or those that concerned local affairs on which the Board thought it was not proper to interfere.51 Most striking of all was the churches’ role in legislative review. In the first twenty years of the century five of the colonies passed laws severely limiting the rights of religious minorities, and all five saw them disallowed by the Board. Over the rest of the century five more discriminatory acts were passed and in each case the Board decided in favour of the minority.

Not only was the Board responsive to interest group pressures; it was relatively more responsive to them than were other parts of the government -notably the ministers and parliament. Unlike the Board, ministers as a rule dealt only with the leaders of the interest groups and dealt with them only in person (one ill and elderly dissenter even felt obliged to apologise to the Duke of Newcastle for sending the Duke a letter he had dictated to his son rather than writing personally).52 The net effect was probably to cream off the top of the interest groups from the rest of the membership. This was certainly true of Sampson Gideon, the highly placed London Jewish financier who left his Bevis Marks congregation; it was probably somewhat true of the Lutheran and Huguenot court chaplains, though they did make a point of preaching to London congregations on a regular basis. It is hard to say how much men like Samuel and Joseph Stennett maintained their closeness to their Baptist congregations after they became confidants of the Duke of Newcastle. Certainly they continued to earn the devotion and respect of fellow ministers. At the same time they seem to have been out of touch with the radical elements in their congregations from the mid-century on. One could go on to suggest doubts about Benjamin Avery, leader of the Dissenting Deputies, or even Micajah Perry, the Virginia tycoon of the 1720s who seems to have drifted away from his mercantile community in the next two decades. Somewhere between a boss, a tribal leader, and simply the wealthy member of the group, many of the eighteenth-century group leaders were partially detachable from the rank and file for whom they spoke.

Another problem the interests found in dealing with the great officers of state was that the kinds of demands which it was appropriate to make of ministers were less well defined than those that could be made of the Board of Trade. In working with ministers interest groups were likely to make some costly demands, demands that the ministers could not grant without antagonising substantial sections of the electorate. Dissenters demanded repeal of the Test and Corporation acts, foreigners demanded blanket naturalization laws, merchants sought to influence foreign policy or customs laws to their own advantage but to the considerable disadvantage of influential competitors. Restrained by political expediency from granting the interests’ domestic demands, ministers were eager enough to encourage the Board of Trade to grant them ‘cheaper’ favours in America which were unlikely to arouse the ire of Englishmen: Englishmen were not reluctant to tolerate and encourage American interests, even if those interests were associated with their English rivals. Rarely was it necessary anyway to disoblige one English group in order to satisfy another on American questions because English lobbyists generally worked for removal of restrictions on their own associates but not for the imposition of restrictions on others.

Thus ministers often denied the highest aspirations of English interests while relying on the Board of Trade to ‘neutralise’ the groups as best they could. They denied the Dissenting Deputies’ demand for repeal of the Test and Corporation Acts while assuring them that they would not appoint an American bishop.53 They may well have felt able to oppose the Virginia merchants in the tobacco excise crisis because they had shortly before sponsored a law making it easier for the merchants to collect their debts in Virginia and had followed their wishes in reviewing a Virginia law for amending the staple of tobacco.54 (Indeed, the lesser merchants who sup-posedly formed the backbone of London radicalism came hat-in-hand to the Board of Trade when American favours were at stake.) Similarly, while denying the non-English communities a general naturalization in England because there was too much local opposition, ministers did later pass such an act with the Board’s support for non-English in the American colonies.

If English interests found the Board more accessible than the officers of state, they also found it easier to work with than Parliament, for appealing to Parliament could require organisation on a scale which many interests were too small or too immature to equal. At the very least the difficulties in approaching ministers repeated themselves since parliamentary success on any issue required the support of the ministers or at least the assurance that they were not hostile. Dissenters discovered this in 1716, for example, when they attempted unsuccessfully to force the ministers to repeal the occasional Conformity and Schism Acts. They re-learned the lesson in 1736 when they pressed Walpole for repeal of the Test and Corporation Acts and had to give up when he opposed them.55 When Henry Pelham showed no enthusiasm for the establishment of an American bishopric in 1749 the Bishop of London had to back down on his campaign to get one.56 When the London merchants responded to American complaints about their supposed inaction against the Townshend Acts by saying they could do nothing without the support of the ministry they passed on a well learned lesson.57

Even if ministers did not oppose them, interest groups found that it took far more resources and organisation to lobby Parliament than to lobby the Board. It was one thing to lobby Board members whose very appointment committed them to some interest in American affairs, but quite another thing to lobby several hundred members of Parliament who were largely indifferent to American affairs. It was necessary to establish committees to go over the voting records of M.P.s and call on those who might be sympathetic.58 Merchants could call on M.P.s from London and the outports; dissenters could remind particular M.P.s of dissenting votes among their constituents.59 When possible the committee had to publish pamphlets or broadsides and distribute them at M.P.s’ homes or at the door of the House. Occasionally they resorted to log rolling (though this was not common until the middle of the century): the West India planter-merchant interest and the Irish linen interest once exchanged support on issues involving molasses and linen. Tobacco and wine merchants combined to seek the opening of French trade during Queen Anne’s War.60 But even the most considerable efforts might come to nothing and interests were driven back to seek pared down demands from the Board of Trade.

The amount of interest group activity before the Board in any one period between 1700 and 1760 was determined by a number of things. The size of the interest groups was one (other merchant groups were slower to develop numbers than the Virginians, while the Virginia group fell off in absolute numbers after the 1720s);61 the relationship of leaders to the rank and file was another (the Virginia group, again, was hurt in the 1740s by the financial crash of some of its leaders and by the preference of other potential leaders to work on their own rather than with the community). Another determinant, and a more important one, was the presence or absence of clusters of issues which required sustained group activity, issues centred around the printing of paper money, for example, or the provincial interpretation of the Toleration Act. Still another was the relationship of the provincial governors with local interests and the governors’ vulnerability to attack in England.

Particular groups waxed and waned over the decades: the Virginia merchants were quite active down to 1715, declined after that and were virtually dormant from the early 1730s to the mid-1750s; the New York merchants were particularly active from 1710 to the early 1730s and then declined, while South Carolina and Massachusetts merchants ‘peaked’ somewhat later. Ecclesiastical lobbies were particularly active in influencing judicial review down to the mid-1720s, then switched their emphasis to influencing the appointment and supervision of colonial governors. Non-English groups became active in the 1730s and 1740s. Whatever the group, the Board seems to have developed a comfortable working relationship with it at some occasion during the years before 1760.

In the years after the accession of George III, however, several related developments began to alter the Board’s working arrangements with the Anglo-American interests. After 1764 the Board considered no petitions from Anglo-American lobbies, heard little testimony, and indeed sought none, from traditional Anglo-American interests. Its reports rarely mentioned the opinions of such interests; it appears to have ignored them in its recommendations. In its reviews of colonial legislation the Board referred only to the opinions of the legal advisor as to the compatibility of the laws with relevant British legislation, never mentioning the views of affected interests as to their workability in America. Hitherto the Board and their legal advisors had made ad hoe decisions about the relevance of English statutes to colonial legislation, bowing on occasion to the wishes of interests involved; now the Earl of Shelburne, briefly president of the Board in 1763, prepared a formal ‘Table of Such English and British Statutes as are expressly or virtually extended to His Majestys Colonies in America’.62 In such circumstances it is difficult to imagine that the Board could have been accommodating interest groups as it had done earlier in the century.

Basically, the Board’s function of balancing off interest groups seems to have been a victim of the ministerial instability of the 1760s in a number of related ways. As a result of the ministerial upheavals, the Board suffered rapid turnovers in its own leadership, a lack of clarity in its relation with the Secretary of State, and ultimately a reduction in its powers, all of which were bound to affect its relationship with interest groups. Between 1730 and 1760 the Board had had only three presidents, each one in office long enough to build up many connections with interests. Between 1761 and 1766 the Board had six, each in office for too short a time to build up such associations. After 1766 the Board was first dominated, then headed by Secretaries of State, and existed only as an office staff to them. Moreover the Board lost many of its powers over the decade, including the right to investigate colonial problems on its own initiative, and the right to receive memorials and petitions directly.63

One can make too much of these changes at the Board, however. The Presidents of the Board were replaced rapidly, but the rank and file membership changed much more slowly, giving some possible continuity in interest group connections. Even as a unit of the staff of the Secretary of State there was nothing to prevent their considering American problems; even after 1766 they continued to review colonial legislation, and there was nothing to prevent their consulting interest groups on this as they had before or receiving petitions from interest groups through the Secretary of State.

More important than changes in the powers of the Board were changes in the attitudes of the ministers which ultimately undercut the Board’s relations with interest groups. In the early 1760s the core of Old Whigs who had dominated English politics since George I was dismissed from office by George III. Their successors were men who represented not only a new generation of English politicians but also a new attitude to interest group politics. Many of the younger generation of politicians brought a new legalism to their politics, an interest in the consistent enforcement of law as an end in itself. A spin-off from the ideas of English legal reformers of the mid-eighteenth century, the new legalism vastly restricted the discretion given the Board in its interpretation of the application of British and colonial laws. No longer could the interpretation of British statutes as a standard of colonial legislation be left flexible; no longer could colonial officials who winked at the laws but got along well with Anglo-American interests be encouraged in office.64

Moreover the retirement of the Old Whigs brought uncertainty on the part of their successors about whether the interests were more loyal to the government or to the Old Whigs themselves. With the exception of the Marquis of Rockingham’s ministry, 1765-6, ministers who succeeded the Old Whigs in office did not share their concern to placate English interests; indeed it is doubtful that they understood the reasons for the Old Whigs’ assumption that political stability depended in part on the successful accommodation of interest groups.65 When Bute was Prime Minister, all the Baptist ministers responsible for distributing the Baptists’ bounty were dismissed and no new ones hired because, as the Baptist leader Samuel Stennett wrote Newcastle, ‘the Dissenters in general apprehend, they were honnored with your Grace’s favor’.66 George Grenville referred to Rockingham’s administration as run by a club of merchants; Lord North advised the London merchants trading to America to return to their counting houses and leave matters to him.67 Merchants did meet with members of Pitt’s cabinet on the Paper Currency Act but little came of their efforts. Only the Rockingham administration worked regularly with the merchants, even offering a cabinet position to Sir William Baker, prominent New York merchant, utilising merchant support in the repeal of the Stamp Act, and drafting trade regulations with their cooperation.68

The interest groups for their part reacted with confusion to the separation of their traditional allies from the government. Hesitant to support a government that was indifferent to them, they were even more hesitant to go into opposition with the Old Whigs who could offer them no rewards and who were, moreover, less in need than the government of the interests’ strongest weapon, information. Their dilemma was further complicated by the rise of agitational’ interests around Wilkes at the end of the decade of the 1760s. Most members of the Anglo-American interests wanted nothing to do with Wilkes, despite his attraction for Americans. Only one-tenth of all the identifiable, politically minded American merchants, for example, signed a Wilkite petition late in 1775. But only one per cent signed the anti-Wilkite petition of 1769, suggesting that most of the American merchants wanted nothing to do with the Wilkite question on either side.69 They ‘did not meddle with politics’70-i.e. political agitation, as one Virginia merchant told his American correspondents. Baptist and Dissenting Deputies seem to have supported the Old Whigs through the election of 1768; in 1773, unsupported by the ministry they mounted their first public drive, verging on the agitational, for the abolition of compulsory subscription to the Articles of Religion.

Thus the decline of the Board’s capacity to placate English interest groups by American favours can be seen as part of a decline in the concern of successive ministries to use them for this purpose. Like the bounty for the Baptists, the Board was cut off because two decades of ministries were not aware of the need to appease Anglo-American interests. This was a part, and not such a small one, of the cause of the unrest in England and America after 1775.

In its decline the Board was no longer able to serve the transatlantic interests as it had done before 1760, but in its heyday it had served them well. Retrospectively it emerges as an early example, if not indeed the earliest, of an institution sorely needed in any developing nation, namely, a clearing house for vital interest group demands. To the extent that it was, the Board made a useful-and hitherto unrecognised–contribution to the stability of eighteenth-century England and America.71

Endnotes

- For representative interpretations of the Board as a victim of ministerial ambitions see Oliver M. Dickerson, American Colonial Government, 1696-1765 (New York, 1962 reprint of 1912 edn.), 67; Arthur Herbert Basye, The Lords Commissioners of Trade and Plantations, Commonly known as the Board of Trade, 1748-1782 (New Haven, 1925), 5, 25, 27, 30-1, and the most sophisticated recent treatment by I. K. Steele, The Politics of Colonial Policy; The Board of Trade in Colonial Administration, 1696-1720 (Oxford, 1968), 170-2. For the other approach see Charles McLean Andrews, The Colonial Period of American History: England’s Commercial and Colonial Policy, IV (New Haven, 1938).

- On this see Gabriel Almond and G. Bingham Powell, Comparative Politics, a Developmental Approach (Boston, 1966), 35, 75-86; Gabriel Almond and James S. Coleman, The Politics of the Developing Areas (Princeton, 1960), 33-5; Myron Weiner, ‘Political Participation: Crisis of the Political Process’, in Leonard Binder et. al., Crisis and Sequences in Political Development (Princeton, 1971), 167-73; Samuel Huntington, Political Order in Changing Societies (New Haven, 1968), 36, 47, 79. On Britain see Graham Wootton, Pressure Groups in Britain 1720-1970 (London, 1975), 1-47; Allen M. Potter, Organised Groups in British National Politics (London, 1961), 29; Samuel H. Beer, ‘The Representation of Interests in British Government: Historical Background’, American Political Science Review, LI (1957), 613-50 and Michael Kammen, Empire and Interest (New York, 1970), passim.

- Leslie A. Clarkson, The Pre-Industrial Economy in England, 1500-1750 (New York, 1972), 198; Charles Wilson, ‘Government Policy and Private Interest in Modern English History’, in Economic History and the Historian, Collected Essays (London, 1969), Ch. 9.

- Douglas R. Lacey, Dissent and Parliamentary Politics in England, 1661-1689 (New Brunswick, New Jersey, 1969), 106-7.

- Alison G. Olson, ‘The Commissiares of the Bishop of London in Colonial Politics’ in Alison G. Olson and Richard Maxwell Brown, eds., Anglo-American Political Relations, 1675-1775 (New Brunswick, N.J., 1970), 109-124.

- Charles Edwin Whiting, Studies in English Puritanism from the Restoration to the Revolution, 1660-1689 (London, 1968), 130.

- J. W. Fortescue, ed., Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and the West Indies, XIII (London, 1900) nos. 763, 2, 352, 396, 2466, 646; Ibid., XIV (London, 1901) nos. 919, 949, XII (London, 1898) no. 1690.

- There appears to have been a group of New England merchants that lobbied the earlier Lords of Trade in 1675/6 for stricter enforcement of the Navigation Acts, but the group did not reappear for a quarter century after that (MS. ‘Journal of ye Lords of the Privy Council Committee for Trade and Plantations’, I, 70, 109, 111, Pennsylvania Historical Society). One might also count the New England Company as a lobby, but its combination of Dissenters and Anglicans in a non-denominational missionary endeavour meant that it did not fit the pattern of other ecclesiastical lobbies. (See William Kellaway, The New England Company, 1649-1776 (New York, 1962), 1-172, passim. For evidence of the Virginia lobby see C.S.P. Col., A. and W.I. XI (London, 1898), nos. 277, 1271, Ibid. XIV, no. 900; Leo Francis Stock, Proceedings and Debates of British Parliaments about North America, 5 vols. (Washington, D.C., 1924), I, 273-4, II, 5, 160; Great Britain, Public Record Office, Colonial Office 5/305, ff. 105-6, 143, 367. For evidence of Huguenot influence see C.S.P. Col., A. and W.I. XII, nos. 1354, 1741. One might consider the Quakers as a third lobby, but as late as the 1690s they still relied almost exclusively on the influence of individuals like Penn rather than on organised efforts of the meeting.

- A. T. Gary, ‘The Political and Economic Relations of English and American Quakers, 1750-1785’, (Oxford, D. Phil, thesis, 1935), 32-3.

- Olson, ‘Commissaries of the Bishop of London’, in Anglo-American Political Relations, 109-24.

- W. K. Lowther Clarke, The History of the S.P.C.K. (London, 1959), Ch. 1.

- Carl Bridenbaugh, Mitre and Sceptre (New York, 1962), 35-9; Address to New England ministers, Feb. or Mar., 1714-15, Cotton Mather to Dr. Daniel Williams et. al. (1715), Thomas Reynolds to Cotton Mather, 9 June 1715, ‘Diary of Cotton Mather 1709-1724’, Massachusetts Historical Society Collections, 7th Ser, VIII (Boston, 1912), 300-3, 317-19.

- Leonard Trinterud, Presbyterianism, the Forming of an American Tradition (Philadelphia, 1949), 27-33; Records of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America, 1706-1788, (New York, 1949), 52, 63, 224-5, 245, 351, 386; unknown to John Matthews, 1719, ‘NYC Churches 30, II’, New York Historical Society; ‘Memorial and Petition of the Presbyterian Church in the city of New York to the Reverend and Honorable the Moderator and Members of the Venerable Assembly the Church of Scotland, Mar. 18, 1766’ (reciting help the Assembly has given them over the century) Dartmouth MS D (W) 1778/II/182, Staffordshire County Record Office.

- Bevis Marks Records: being contributions to the History of the Spanish and Portuguese Congregation of London Pt. 1, The Early History of the Congregation from the Beginning until 1800 (Oxford, 1940), 35.

- ‘Threadneedle Street Letterbook, to and from’, Huguenot Society Library, London. Letter of 27 Aug., 1699, 25 Aug., 1700, 19 May, 1700.

- Garold N. Davis, German Thought and Culture in England, 1700-1770 (Chapel Hill, 1969), 45.

- Bryant Lillywhite, London Coffee Houses (London, 1963), 387, 408, 447-8.

- E. A. Wrigley, ‘A Simple Model of London’s Importance in Changing English Society and Economy, 1650-1750’, Past and Present, XXXVII (1967), 44-70.

- For the concentration of non-conformists in London see Harry Grant Plum, Restoration Puritanism, A Study of the Growth of English Liberty (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1943), 71. For London’s help to the provinces see Duncan Coomer, English Dissent under the Early Hanoverians (London, 1946), 56, and Bridenbaugh, Mitre and Sceptre, 36.

- See Frank Tomkins Melton, ‘London and Parliament, an Analysis of a Constituency, 1661-1702’ (University of Wisconsin Ph.D. thesis, 1969) esp. 15, 164-6, 231.

- Malcolm R. Thorpe, ‘The English Government and Huguenot Settlement, 1680-1702’ University of Wisconsin Ph.D. thesis, 1972) 71; ‘The Archives of the French Protestant Church of London, A Handlist’, comp. Raymond Smith Huguenot Society Publications L (London, 1972), 89-92.

- Albert M. Hyamson, A History of the Jews in England (London, 1928), 188.

- Raymond Clarke Mensing, Jr., ‘Attitudes on Religious Toleration as expressed in English Parliamentary Debates, 1660-1919’ (Emory University Ph.D. thesis, 1970) 153-4.

- P. M. G. Dickson, The Financial Revolution in England (New York, 1967), 249-303.

- See A. H. Carpenter, ‘Naturalization in England and the American Colonies’. American Historical Review, IX (1903-4), 292-3; Caroline Robbins, ‘A Note on General Naturalization under the Later Stuarts and a Speech in the House of Commons on the Subject in 1664’, Journal of Modern History, XXXIV (1962), 168-177.

- For representative examples of the behaviour of interest groups in the Restoration see Margaret Priestly, ‘London Merchants and Opposition Politics in Chaires II’s Reign’, Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research, XXIX (1956), 205-19; Gerald R. Cragg, Puritanism in the Period of the Great Persecution, 1660-1688 (Cambridge, 1957); Whiting, Studies in English Puritanism, 20, 32, 63, 82, 95-6; J. R. Maybee ‘Anglicans and Non Conformists, 1679-1704, A study of the Background in Swift’s, A Tale of Tub’ (Princeton University Ph.D. thesis, 1942) 14–189.

- Elmer B. Russell, ‘The Review of American Colonial Legislation by the King in Council’, Columbia University Studies in History, Economics, and Public Law, LXIV (New York, 1915), 19-37.

- This is not to suggest that the Americans had no way of forwarding their demands to London before the end of the century. Earlier, however, Americans had used highly placed individuals, friends or relatives, to put their case at court. See for example, Robert C. Black, Jr., The Younger John Winthrop (New York, 1966), Chs. 16 and 17; William Fitzhugh and his Chesapeake World, 1676-1701, ed. Richard Beale Davis (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1963), 351, n6; Richard S. Dunn, ‘John Winthrop Jr. and the Narragansett Country’, William and Mary Quarterly, 3d Ser. XIII (1956) 68-86; Bernard Bailyn, The New England Merchants in the Seventeenth Century (Cambridge, Mass., 1955), 174–7; Gary, ‘The Political and Economic Relations of English and American Quakers, 1750-1785’, Ch. 1.

- New England Quakers did this, for example, in 1692, 1693, and 1695, when they asked English Quakers for help in obtaining the disallowance of laws that had already been approved (Arthur John Worrall, ‘New England Quakerism, 1656-1830’, Indiana University Ph.D. thesis, 1969, 86).

- The Board’s Commission is published in Documents relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York, ed. E. B. O’Callaghan, IV (Albany, 1854), 145-148.

- Avery to Newcastle, 16 Feb., 1741, Add. Ms. 32, 699, f. 62. Avery was also concerned that Newcastle might suggest to the Massachusetts assembly the name of a particular person to be chosen as the colony’s agent in London. He opposed this, partly because the legislature had already nominated Jasper Mauduit, well liked on the Exchange, and partly because the nomination was a local issue on which ‘it is hoped, that his Majesties’ servants here will hardly think fit to interpose’ (Avery to Newcastle, 15 Dec. 1758, Add. Ms. 32, 886, f. 334).

- 23 Mar. 1749/50, Journals of the Board of Trade, 1749-53 (London, 1932), 46.

- 3 July, 1735, J.B.T. 1734-41 (London, 1930), 35.

- 17 April, 1 June, 2 Oct., 1705, J.B.T. 1704-9 (London, 1920), 127, 141, 165.

- For example, in 1758 the Board asked the agent of Virginia and Maryland ‘to take the opinion of the merchants and Traders to Virginia and Maryland upon the utility of a lighthouse so proposed .. .’ James Abercromby to Gov. Fauquier, 28 Dec. 1758, Abercromby Letter Book, Virginia Historical Society. On 25 Feb. 1705/6 Mr. Blakeston was sent to poll the London merchants about the timing of convoys to Virginia. J.B.T. 1704-9, 226-7.

- The Board’s weekly schedule was arranged and ordered to be posted ‘for the benefit of people who have business’ on 20 Nov. 1717. J.B.T. 1714/15-1718 (London, 1924), 296.

- Micajah Perry to William Popple, 11 Oct. 1711, C.0. 5/1363, f. 333. In 1742 twenty Quakers attended the Board in a hearing on charges against the Pennsylvania assembly. (John Kinsey to Israel Pemberton, 4 mo 28, 1742, Pemberton Papers, Pa. Hist. Soc.) In 1734 ‘A large number of Friends’ attended on the Pennsylvania Maryland boundary dispute. (London Meeting for Sufferings to Quarterly Meeting of Friends in Chester, Newcaslte, Kent, and Sussex counties, 12 mo 28, 1734, London Meeting for Sufferings, Epistles Sent, II, 495-6).

- Some of the English merchants who had originally pressed for the creation of the Board in the 1690s had hoped that merchants might be represented on the Board, and some proposals went so far as to suggest an elected council of merchants (R. M. Lees, ‘Parliament and the Proposal for a Council of Trade, 1695-6’, English Historical Review, LIV (1939), 46-7). But had some groups been represented and others not, the Board would have been regarded as partial; had all the important interests been represented, politicians might have distrusted the Board as a rival to Parliament.

- On this see L. S. Sutherland, ‘Edmund Burke and the First Rockingham Ministry’, E.H.R. XLVII (1932), 46-72.

- This is suggested by Bladen’s passing on their nominations for councillorships (Recommendations for colonial councillors: Virginia. C.O. 324/48).

- Oswald’s connections are suggested in Menwrials of the Public Life and Character of the Right Honorable James Oswald of Dwmiker (Edinburgh, 1825), passim.

- 6 Feb. 1753, The Reverend Samuel Davies Abroad, The Diary of a Journey to England and Scotland, ed. George William Pitcher, (Urbana, Ill., 1967), 69-70.

- Recommendations for colonial councillors: Virginia, C. 0. 324/48. All estimates of nominations are based on this volume.

- 13 Feb. 1701, Acts of the Privy Council, America and the West Indies II (London, 1910), no. 814.

- C.O. 5/995, f. 72, Instruction no. 60.

- 14 Mar. 1734, J.B.T. 1734—41 (London, 1930), 10.

- Representation to the King, 10 June, 1730, C. 0. 5/400, f. 286.

- Hunter to William Popple, 1 Oct. 1718, C. 0. 5/1124. ff. 52-4.

- On 13 June, 1735 Purry’s petition on behalf of a South Carolina appropriation act was considered favourably (J.B.T. 1734—41, 25). On 15 May, 1745 the Board consulted Moravian leaders about a New York act discriminating against them (J.B.T. 1741-9, London, 1931, 164–5). On 18 Nov. 1745, they read a letter from the Moravian agent in favour of a Pennsylvania naturalization act (Ibid., 213-14).

- Spotswood to Board, 27 Sept. 1718. C. 0. 5/1365, ff. 1767.

- Merchants trading to Jamaica were scolded in 1736: ‘The Board then informed them that they are surprised the merchants should lay memorials before H. M. without proof’. 15 April, 1736, J.B.T., 1734—41, 102. On another occasion the legal adviser to the Board advised ‘I am of opinion that the Merchants of London Trading to New York, are not proper to object to what debts ought to be allowed or disallowed, this being a thing which is absolutely in the power of The General Assembly’. West to Board, 22 April, 1719. C. 0. 5/1124, ff. 64–71.

- ‘I am ashamed to think that I shou’d address such a Personage by an Amanuensis, but necessity has oblig’d me under much pain and weakness to dictate to my son these lines at my bedside’. Jos. Stennet to Newcastle 7 Nov. 1757, Add. Ms. 32, 867, f. 455.

- For example, see Bridenbaugh, Mitre and Sceptre, 44–5; Maurice Armstrong, ‘The Dissenting Deputies and the American Colonies’, Church History, XXIX (1960), 302; Susan Martha Reed, Church and State in Massachusetts (Urbana, Ill., 1914), 141; Minutes of the Dissenting Deputies, 5 May, 1749 (Guildhall MS 3083/1 p. 315).

- Board of Trade to King, 29 May, 1731, C. 0. 5/1366, ff. 61-71.

- Richard Burgess Barlow Citizenship and Conscience, a Study in the Theory and Practice of Religious Toleration in England during the Eighteenth Century (Philadelphia, 1862), 68-9, 82.

- Arthur Lyon Cross, The Anglican Episcopate and the American Colonies (Cambridge, Mass., 1924), 122-5.

- William Nelson to John Norton, 19 July, 1770, William and Thomas Nelson Letterbook, 1766-75; Jack M. Sosin, Agents and Merchants (Lincoln, Nebraska, 1965), 124; Michael Kammen, A Rope of Sand (Ithaca, New York, 1968), 199.

- For an example of the Quakers’ efforts to do this, see I. K. Steele, ‘The Board of Trade, the Quakers, and Resumption of Colonial Charters, 1699-1702’. W.M.Q., 3 Ser. XXIII (1966), 596-619. For a similar example, the efforts of the London merchants trading to Virginia, see Jacob Price, France and the Chesapeake (Ann Arbor, 1973), 512-29.

- ‘I take the liberty to acquaint your Grace, that agreeably to your Grace’s request, our friends have wrote to a great number of Ministers and Gentlemen that have influence in the County of Essex, warmly recommending Mr. Luther to their favor. This, we have done not doubting upon your Grace’s recommendation that he is a steady friend to the present family and to our liberties civil and religious’. Samuel Stennet to Newcastle, 6 July, 1763, Add. Ms. 32, 949, f. 277. Dissenters threatened to withdraw their support from the ministry in 1716 ‘for without their support they cannot be chosen’ (Barlow, Citizenship and Conscience, 69, citing William Matthews, ed., The Diary of Dudly Ryder, London, 1939, 361); Bridenbaugh, Mitre and Sceptre, 42.

- Price, France and the Chesapeake, 578.

- Jacob Price, ‘The Economic Growth of the Chesapeake and the European Market, 1697-1775’. Journal of Economic History, XXIV (Dec., 1964), 510.

- Shelburne Papers, V. 85 p. 250, William L. Clements Library, Michigan.

- Administrative changes affecting the Board are summarised in Arthur Herbert Basye, The Lords Commissioners of Trade and Plantations (New Haven, 1925), Chs.111 and IV.

- On this, see Alison G. Olson, ‘Parliament, Empire, and Parliamentary Law’ in Three British Revolutions, ed. J. G. A. Pocock (Princeton).

- The ‘Old Whig’ association with interest groups was most pronounced in the period of Henry Pelham and the Duke of Newcastle but it dated back to the beginning of the century. See Geoffrey Holmes, British Politics in the Age of Anne (New York, 1967), 105. For a good example of Newcastle’s awareness of the importance of interest groups see the discussion of proposals to appoint an Anglican Bishop for the colonies, in Cross, The Anglican Episcopate, 114-25, App. A, 324-30.

- This is calculated by comparing the number of American merchants listed in ‘The Pro-American Petitioners of 11 October 1775’, App. A of John A. Sainsbury, ‘The Pro-American Movement in London, 1769-1782: Extra Parliamentary Opposition to the Government’s American Policy’, (McGill University Ph.D. thesis, 1975) with my own card list of merchants who signed any petition or testified before Parliament on the Board of Trade between 1763 and 1775.

- Sosin, Agents and Merchants, 175-6.

- Sutherland, ‘Edmund Burke and the First Rockingham Ministry’, E.H.R., XLVII (1932), 46-72.

- George Rude, ‘The Anti-Wilkeite Merchants of 1769’, Guildhall Miscellany, II (1965), 283-304.

- Thomas Nelson to Samuel Athawes, 7 Aug. 1774, William and Thomas Nelson Letter Book 1766-1775, Va. Hist. Soc.

- The author would like to thank Professor Donald Gordon and Professor I. K. Steele for their criticisms of the article and Professor Jon Butler for the use of his notes on the Huguenot correspondence. She also wishes to thank the General Research Board of the University of Maryland for financial assistance in preparing the article.

Chapter (33-50) from The British Atlantic Empire before the American Revolution, edited by Peter Marshall and Glyn Williams (Routledge, 07.08.2005), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.