Understanding Bronze Age Gaza demands a critical eye toward modern narratives that impose fixed identities on ancient peoples.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Between Sea and Sand

To write of Gaza in the Bronze Age is to reach deep into the palimpsest of ancient civilization, where sea-borne traders and land-rooted peoples coalesced into something far older and more complex than the war-torn geography of the modern Strip would suggest. Beneath the violence of the present lies a deeper and subtler drama, the gradual emergence of Canaanite culture along the southern Levantine coast during the third and second millennia BCE. Gaza, sitting astride the maritime crossroads between Egypt and the Levant, functioned not only as a trade conduit but as a cultural crucible in which diverse coastal and inland traditions converged, collided, and coalesced.

Archaeological evidence and ancient textual sources reveal a world of fluid identities, shifting polities, and dynamic interactions. The Bronze Age peoples of Gaza were not static figures frozen in time but active agents navigating the tides of imperialism, trade, and environmental change. Understanding their emergence requires looking beyond the tired categories of “Canaanite” or “Philistine” to examine the lived textures of settlement, language, and ritual that shaped the fabric of Bronze Age Gaza.

The Geographic Theater: Gaza’s Liminal Position

A Borderland of Influence

Situated at the nexus between Egypt and the wider Levant, Gaza was never merely a local settlement. It was a space defined by permeability, of goods, gods, and governance. From the earliest third millennium BCE sites such as Tell es-Sakan, evidence suggests Egyptian presence in the form of mudbrick fortifications, ceramics, and urban planning consistent with Old Kingdom patterns.1 This was no one-sided domination but rather a hybridizing interaction.

The borderland nature of Gaza shaped the material culture of its inhabitants. Egyptian styles mixed with local pottery forms, while burial practices drew from both indigenous Levantine customs and Nile Valley precedents. Scholars such as Trude Dothan and Amihai Mazar have emphasized the “Egyptian-Levantine interface”2 that Gaza represented, a place where elites might adopt foreign symbols to assert status, even while maintaining local continuity.

Environmental Constraints and Coastal Fertility

The physical geography of Gaza, a narrow coastal plain hemmed by the Mediterranean and semi-arid hinterlands, fostered both opportunity and fragility. Seasonal rainfall, though limited, supported barley and emmer agriculture, while access to maritime trade routes enabled contact with Byblos, Ugarit, and Cyprus. Yet this fertility was always precarious.

Bronze Age drought cycles, now better documented through paleoenvironmental data from the Dead Sea basin and coastal cores, reveal that Gaza’s settlement patterns fluctuated in response to aridification events.3 These pressures likely intensified reliance on trade and external support, tightening ties to Egypt in some periods and loosening them in others.

Cultural Emergence: Defining the Canaanite in Gaza

The Elusive Canaanite Identity

To speak of “Canaanites” in Bronze Age Gaza is to court anachronism. The term “Canaan” first appears in Egyptian texts of the 15th century BCE, referring to a geopolitical region rather than a coherent people.4 Biblical and classical sources later reified the term into an ethnic identity, but in the Bronze Age, what we call “Canaanite” was a confluence of linguistic, artistic, and religious patterns without a single center.

Linguistically, the people of Gaza likely spoke an early Northwest Semitic dialect, evidenced indirectly through later Ugaritic texts and Amorite names recorded in Egyptian sources.5 Religiously, the region shows signs of devotion to deities like Baal, Asherah, and Resheph, whose cultic imagery appears in figurines and temple architecture from sites such as Tel Haror.6 These practices were not uniform but localized, often syncretized with Egyptian symbols or influenced by northern Syrian models.

Urbanization and Power Structures

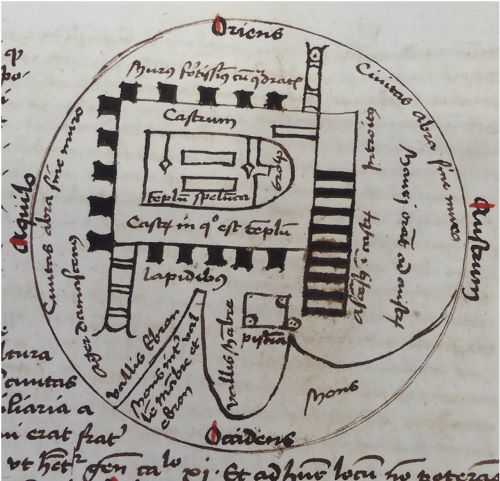

By the Middle Bronze Age (c. 2000–1550 BCE), Gaza had developed into a network of fortified towns linked by trade and patronage. The spread of rampart fortifications and public granaries at sites like Tel el-Ajjul points to increasing centralization and elite management of resources.7

Tel el-Ajjul in particular serves as a keystone for understanding Bronze Age Gaza. The site, with its luxury Cypriot wares, scarabs bearing names of Hyksos rulers, and elaborate tombs, reveals a cosmopolitan elite stratum embedded in Mediterranean exchange networks.8 Far from being peripheral, Gaza was at the forefront of Canaanite urban evolution, and its elites likely played a role in mediating regional politics between Egypt, inland Canaan, and the sea.

Maritime Currents: Coastal Peoples and Sea Networks

Before the Philistines

The popular imagination often begins Gaza’s story with the arrival of the Philistines around 1200 BCE. Yet the centuries preceding that upheaval were no less maritime. Bronze Age Gaza was a node in seaborne networks stretching across the eastern Mediterranean. Amphorae from Minoan Crete, Mycenaean pottery, and oxidized bronze ingots suggest deep commercial ties.9

This web of trade fostered what some scholars call a “Coastal Koine, a shared cultural language that included artistic motifs, weight systems, and possibly cultic practices. Gaza, along with cities like Ashkelon and Jaffa, was part of this floating world of middlemen and migrants.

The concept of “coastal peoples” in this period is inherently plural. Merchant communities, seasonal sailors, and foreign settlers all contributed to the region’s hybridity. As Mycenaean influence waned and the so-called “Sea Peoples” began to arrive in the early 12th century BCE, this maritime culture transformed, but it did not begin with Philistine colonization.

The Collapse and Cultural Reinscription

By the end of the Late Bronze Age, the Eastern Mediterranean experienced a wave of political collapse and demographic shifts often referred to as the “Bronze Age Collapse.” For Gaza, this meant the disruption of trade routes, the breakdown of Egyptian hegemony, and the arrival of new populations, possibly including Aegean migrants later identified as Philistines.10

Yet the archaeological record suggests continuity as well as change. At Tel el-Ajjul, Mycenaean-style pottery appears alongside Egyptian forms and local wares, indicating not sudden replacement but gradual transformation. Rather than a clean break, the emergence of Philistine Gaza can be seen as the culmination of centuries of coastal hybridity.

Conclusion: Inheritance of a Coastal Identity

The Bronze Age peoples of Gaza were neither wholly Egyptian nor purely Canaanite. They were, instead, products of a shoreline world shaped by exchange, adaptation, and environmental flux. Gaza’s role as a coastal liminal zone, caught between desert and sea, empire and autonomy, produced a distinct and resilient culture that left its imprint well into the Iron Age.

Understanding Bronze Age Gaza demands a critical eye toward modern narratives that impose fixed identities on ancient peoples. The Canaanites of Gaza were not passive recipients of outside influence but active participants in a cultural dialogue that reached from the Nile Delta to the Aegean. Their story, buried beneath the sands of millennia and often overshadowed by later conflict, remains one of the Levant’s most evocative and underappreciated legacies.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Pierre de Miroschedji, “The Excavations at Tell es-Sakan (Gaza Strip): A Case Study of the Egyptian Presence in Southern Canaan during the Early Bronze Age,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 308 (1997): 1–24.

- Trude Dothan and Amihai Mazar, The Archaeology of the Land of the Bible, Volume 1: 10,000–586 BCE (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 177.

- Israel Finkelstein and Thomas Litt, “Holocene Climate and Settlement Patterns in the Southern Levant,” Quaternary Science Reviews 29, no. 19–20 (2010): 2728–34.

- Donald Redford, Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992), 109.

- Richard S. Hess, Amorite Personal Names in the Mari Texts (Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 1993), 8–14.

- Amnon Ben-Tor, “Hazor and the Archaeology of the Tenth Century BCE,” Israel Exploration Journal 48, no. 1–2 (1998): 1–37.

- Graham Philip, “The Early Bronze Age of the Southern Levant: A Landscape Approach,” Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 6, no. 2 (1993): 117–63.

- Peter M. Fischer, “Cypriot Pottery in Tel el-Ajjul: Trade, Chronology, and Political Implications,” Studies in the History and Archaeology of Palestine 4 (2003): 203–30.

- Eric H. Cline, Sailing the Wine-Dark Sea: International Trade and the Late Bronze Age Aegean (Oxford: BAR International Series, 1994), 66–92.

- Assaf Yasur-Landau, The Philistines and Aegean Migration at the End of the Late Bronze Age (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 45–98.

Bibliography

- Ben-Tor, Amnon. “Hazor and the Archaeology of the Tenth Century BCE.” Israel Exploration Journal 48, no. 1–2 (1998): 1–37.

- Cline, Eric H. Sailing the Wine-Dark Sea: International Trade and the Late Bronze Age Aegean. Oxford: BAR International Series, 1994.

- Dothan, Trude, and Amihai Mazar. The Archaeology of the Land of the Bible, Volume 1: 10,000–586 BCE. New York: Doubleday, 1992.

- Finkelstein, Israel, and Thomas Litt. “Holocene Climate and Settlement Patterns in the Southern Levant.” Quaternary Science Reviews 29, no. 19–20 (2010): 2728–2734.

- Fischer, Peter M. “Cypriot Pottery in Tel el-Ajjul: Trade, Chronology, and Political Implications.” Studies in the History and Archaeology of Palestine 4 (2003): 203–230.

- Hess, Richard S. Amorite Personal Names in the Mari Texts. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 1993.

- Miroschedji, Pierre de. “The Excavations at Tell es-Sakan (Gaza Strip): A Case Study of the Egyptian Presence in Southern Canaan during the Early Bronze Age.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 308 (1997): 1–24.

- Philip, Graham. “The Early Bronze Age of the Southern Levant: A Landscape Approach.” Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 6, no. 2 (1993): 117–163.

- Redford, Donald. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992.

- Yasur-Landau, Assaf. The Philistines and Aegean Migration at the End of the Late Bronze Age. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.25.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.