Roman gate at Porta Roman / Wikimedia Commons

Introduction

In the late-republican period a wall was built for the protection of Ostia. Visitors will often look in vain for it, because so little has been preserved. It is attested to the west, south and east of town, but it is not known whether it continued along the Tiber. If it did not, it was over 2100 meters long. Towards the west it must have ended at or near “Tor Boacciana” (in its present state largely mediaeval), a lighthouse or watch-tower near the mouth of the Tiber. Together with the river the wall enclosed an area of approximately 69 hectares.

A concrete nucleus was faced on the outside with small, square tufa blocks placed on one corner. The pattern is rather irregular (opus quasi-reticulatum). The inside did not have a facing and may have been reinforced by beaten earth. There were three major gates, the modern names of which are Porta Marina, Porta Laurentina and Porta Romana. In between were round towers, a square tower (close to the Tiber), and minor gates (only one is indicated on the plan; however, Calza unearthed many stretches of the wall, but not all of it; at least one other minor gate was found in the late 1990’s by Heinzelmann c.s.).

The city walls, indicated in green. / After Zevi 1998, fig. 1.

The wall has often been ascribed to the early first century BC, to Sulla (88 – 79 BC). However, researchers have always agreed that there is no hard evidence for this dating. A crucial date is the year 67 BC, when pirates destroyed a fleet in Ostia and plundered the city. Cicero commented: “A particularly scandalous blot on our reputation was the disastrous raid on Ostia” (De Imp. Cn. Pompeii 33; translation Penguin, M. Grant). Does this event imply that Ostia was not yet protected by a wall?

Important information is offered by two virtually identical inscriptions that were attached to the upper part of either side of the Porta Romana, the gate that was used by those who entered Ostia coming from Rome, or left Ostia to visit the Urbs. The gate as we see it now was rebuilt in the late first century AD, probably during the reign of Domitian (81 – 96 AD). The inscriptions belong to this phase, but record the building history.

The inscriptions were made of the famous marble from the Greek island Paros. The slabs measured approximately 5.60 x 1.36 m. All that remains are many fragments. Various readings have been proposed in the past (Vaglieri, Wickert). New fragments were found in the store rooms by Zevi, and in 1998 he could propose a new reading. Characteristics such as the diminishing height of the lines and the finish of the back side enabled him to find for most fragments first a vertical place, then a horizontal place within a single line. The inscription is now reconstructed as follows:

SENATVS POPVLVSQVE ROMANVS

COLONIAE OSTIENSIVM MVROS ET PORTAS DEDIT

M. TVLLIVS CICERO CO(n)S(ul) FECIT CVRAVITQUE (or LOCAVITQUE, or a similar verb)

P. CLODIVS PVLCHER TR(ibunus) PL(ebis) CONSVMMAVIT ET PROBAVIT

PORTAM VETVSTATE CORRVPTAM [—]

In other words: the Senate of Rome gave walls and gates to the colony of the Ostians; Cicero, when he was consul (63 BC), oversaw the construction; Clodius, arch-enemy of Cicero, finished the work when he was tribune of the people (58 BC). Line 5 cannot be reconstructed completely. It mentions the rebuilding in the first century AD.

Unfortunately we have few written sources about Cicero’s year as consul. Nevertheless Zevi, properly acknowledging helpful suggestions by others, was able to trace this event in Cicero’s writings. In his works we find references to what Zevi calls a “war of inscriptions”: Clodius replaced Cicero’s name by his own. Cicero’s comments were bitter:

[De Har. Resp. 27, 58]

[Ad Fam. I,9,15]

In the latter passage Cicero is talking about “his monument”, but explains that it is only “his” because he carried out work ordered by the Senate; it was not his own initiative, financed by booty. And on this monument, he adds, Clodius was allowed to place his name with letters of blood. As to the monuments mentioned in the first passage, Zevi argues that, in spite of the plural (monumenta), Cicero refers to one monument only: the monumentum of the second text. This monument was no other than the walls and gates of Ostia, the construction of which was for Cicero one of the major achievements in his life. His concern about ports, by the way, is evident from another text, about good public spending:

[De Off. II,17,60]

The decision at the end of the first century AD to restore the name of Cicero and the role of the Senate on the Porta Romana may have been influenced by Pliny the Younger, who lived near Ostia.

In the early Imperial period there was no need for a protective wall any longer. The entire area inside the wall soon became built-up. Starting in the period of Augustus buildings were erected next to, on top of, and beyond the wall. During the reign of Vespasian the walls were changed to an aqueduct. In late antiquity, when Rome itself and her harbours were threatened by barbarians and eventually invaded, the wall was not restored. In the fifth century Ostia was of little economic significance. Portus was by now the main harbour of Rome. In 410 AD Alaric’s Goths captured Portus, but paid no attention to Ostia. Portus was sacked by Vandals led by Gaeseric in 455 AD. They may also have plundered Ostia. Somewhere in the fifth or sixth century the Ostians used the theatre as a fortress.

The scant remains of the secondary gate to the south of the Porta Romana, seen from the east. Discovered in 1856. / Photograph: Jan Theo Bakker.

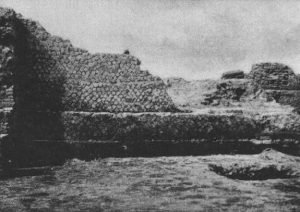

Left: The remains of a round tower, in the angle that is made by two stretches of the wall. / From SO I, Tav. 27.

Right: A stretch of the wall to the south of the Porta Romana. / From SO I, Tav. 27.

Porta Romana

Regio II

Plan of the gate. / From SO I, fig. 25.

The Porta Romana or Roman Gate belongs to the city walls of the first century BC. Visitors from Rome followed the Via Ostiensis and entered Ostia through this gate. It was excavated in 1911.

The original gate was at a much lower level than the present level. It was made of large tufa blocks, and consisted of two rooms. Grooves for wooden doors were found on the east side (the outer side). On either side of the gate is a square tower, with sides of six metres.

During the reign of Domitian (81-96 AD) the level was raised, and the gate rebuilt. Marble architectural decoration was added. Large inscriptions on either side recorded the building history of the gate (for details see the topic The city walls). A statue of the winged Minerva-Victoria, found on the nearby Piazzale della Vittoria, formed part of the decoration of the upper part. Minerva was the favourite goddess of Domitian.

To the north-east of the gate is the so-called Cippus of Salus Augusti. It was found in 1910. It is a marble base for a statue (1.20 x 1.20 x 1.05), with the inscription:

SALVTI CAESARIS AVGVST

GLABRIO PATRONVS COLONIAE D(ecreto) D(ecurionum) F(aciundum) C(uravit)

On top of the base was a statue of Salus Augusti, the Health of the Emperor (a woman with a snake). It was erected by a member of a well-known Ostian family, the Acilii Glabriones. He was patron of the colony. The base is at the lower level, and was installed in the first half of the first century AD, when an Emperor visited Ostia. Here we may think of Claudius, who was a frequent visitor of Ostia when the harbour at Portus was built.

The lower part of the south side of the gate, seen from the north-west.

Left: Remains of the Domitianic marble decoration of the gate, attached to the north side. Seen from the south-west.

Center: Fragments of one of the Domitianic inscriptions, with modern additions. / Photograph: Laura Maish-Bill Storage.

Right: The Cippus of Salus Augusti.

Left: The statue of Minerva-Victoria.

Right: Reconstruction drawing of the gate, seen from the east, by Italo Gismondi. / From Zevi 1998, fig. 18.

Mitreo Aldobrandini and Torre sul Tevere

Regio II – Insula I – (II,I,2) and (II,I,3)

This mithraeum was excavated in 1924. It was found 150 metres to the north of the Porta Romana on property owned by the Aldobrandini-family, and is still not accessible to the public. The south part of the shrine was not excavated. The back wall (north wall) was set against a tower belonging to the city wall from the first century BC. The tower was built with large tufa blocks. The east wall was set against the city wall (opus quasi reticulatum). The shrine was built in opus latericium, and has been dated to the late second century AD.

The northern part of the podia, lined with white marble, was unearthed. To the north of the podia is a short west-east running corridor, the floor of which was decorated with coloured marble, forming geometric motifs. The back part of the shrine was at a slightly higher level, and could be reached along two treads. Here some brick piers were excavated, lined with marble. A few marble slabs created a table.

Plan of the shrine. / From SO II, fig. 8 = NSc 1924, fig. 1.

A base or altar was set against the back wall (h. 0.60, w. 2.12), lined with a marble slab with the inscription:

DEVM VETVSTA RELIGIONE

IN VELO FORMATVM ET VMORE OBNVBI

LATVM MARMOREVM CVM

THRONO OMNIBVSQ(ue) ORNAMENTIS

A SOLO OMNI IMPENDIO SVO FECIT

SEX(tus) POMPEIVS MAXIMVS PATER

Q S S EST

ET PRAESEPIA MARMORAVIT P(edes) LXVIII IDEM S(ua) P(ecunia)

The inscription informs us that a painting of Mithras on cloth had been damaged by moisture, and was replaced by “father” (pater) Sextus Pompeius Maximus by a marble depiction. In line 1 is a reference to “ancient religion”, which may mean that the cloth was imported from the east, where the origins of Mithras lay. A throne is also mentioned, probably the structure set against the back wall, which may have been a combined altar and base. The abbreviation Q S S EST has been explained as qui sacerdos (or sacratus) solis est (“who was priest (or ordained as priest) of the Sun”), and as qui supra scriptus est (“whose name is written above”). The praesepia, 68 feet long (20 metres) are probably the podia, that is: two podia of 10 metres. The most important objects found in the shrine are three small tufa altars, a small herm of Silenus (with traces of blue paint in his hair), and a marble relief of Silvanus.

A bronze inscription (0.42 x 0.29), now in the British Museum, may also come from this shrine. Below a small bust of Sol is written:

SEX POMPEIO SEX FIL

MAXIMO

SACERDOTI SOLIS IN

VICTI MT PATRI PATRVM

QQ CORP TREIECT TOGA

TENSIVM SACERDO

TES SOLIS INVICTI MT

OB AMOREM ET MERI

TA EIVS SEMPER HA

BET

This inscription was put up by all priests of Mithras in Ostia and Portus, in honour of Sextus Pompeius Maximus, “father of the fathers”. Apparently he was the leader of the cult of Mithras in Ostia. We also learn that he was in charge of one of Ostia’s ferry services.

In 1637 Cardinal Domenico Ginnasi built a hospital and a chapel of San Sebastiano to the south of the mithraeum.

Left: The shrine seen from the south. Note the large tufa blocks of the tower of the city wall in the background, and the marble floor in the foreground. / SO II, Tav. V, 3.

Right: The bronze inscription in the British Museum. / Photograph: Eric Taylor.

Opus quasi reticulatum. / Photograph: Antonio Veronese.

Left: The back part of the shrine and opus latericium. / Photograph: Antonio Veronese.

Right: Large tufa blocks and opus quasi reticulatum. / Photograph: Antonio Veronese.

Left: The hospital of Domenico Ginnasi. / Photograph: Antonio Veronese.

Right: The mithraeum next to the hospital. / Photograph: Antonio Veronese.

Left: The hospital and to the right the chapel of San Sebastiano. / Photograph: Antonio Veronese.

Center: The coat of arms of Domenico Ginnasi. / Photograph: Antonio Veronese.

Right: The chapel of San Sebastiano. Photograph: Antonio Veronese.

Porta Laurentina

Regio IV

The Porta Laurentina or Laurentine Gate belongs to the city walls of the first century BC. It received its (modern) name from the village Laurentum, to the south of Ostia. Beyond the gate was a huge necropolis, starting at a distance of c. 50 metres. The gate was excavated in 1938-1942.

Plan of the Porta Laurentina. / SO I, fig. 26.

The gate consists of a single room, made of large tufa blocks. On the south side are grooves for the wooden doors. In the east side a hole has been preserved, in which a beam that blocked the door was inserted. On either side of the gate is a square tower, with sides of 5.85 metres.

The Porta Laurentina seen from the south. / Photograph: Jan Theo Bakker.

Porta Marina

Regio III

The Porta Marina or Sea Gate belongs to the city walls of the first century BC. It received its (modern) name from the nearby beach. The gate was excavated in 1938-1942.

Plan of the Porta Marina. / SO I, fig. 28.

The gate consists of a single room, made of large tufa blocks. On the south side are grooves for the wooden doors. Pivot-holes have also been preserved. On either side of the gate is a square tower, with sides of 4.40 to 4.50 metres. In the first century AD the gate was razed to the ground. In the years 210-235 AD the Bar of Alexander and Helix (IV,VII,4) was built on the east side. As a replacement an arch decorated with marble was built, five metres to the south. Between the gate and the arch a mediaeval lime-kiln was found.

The Porta Marina seen from the south. / Photograph: Jan Theo Bakker.

Ninfeo

Regio III – Insula VI – III,VI,4

Plan of the nymphaeum. / After SO I.

This public nymphaeum is the monumental facade of a water reservoir. The structure was built in opus latericium and belongs to the Hadrianic period. It probably supplied the fountains in the nearby Case a Giardino (Garden Houses).

The reservoir consists of two lower and two upper rooms. The lower rooms have barrel vaults. They may have been basins, or simply supported the upper rooms. The latter were probably fed by a branch of the aqueduct, that was supported by the republican city wall. Two walls connect the basins and the city wall, that is 4.50 m. to the west. They presumably supported conduits. Furthermore there are two vertical recesses in the city wall, at the point where the two walls begin. They probably contained pipes. On either side of the reservoir is a service area, with a staircase leading to the upper rooms. The nymphaeum has three niches, a semicircular niche in the centre, and two rectangular niches on either side. In front of the niches is a basin that was filled with water through a hole below the left niche. Travertine stones in front of the basin have depressions for buckets.

The nymphaeum seen from the north-west. / Photograph: Jan Theo Bakker.

Plan and section of the nymphaeum. / From Scrinari-Ricciardi 1996, I, fig. 179.

Reconstruction drawing of the nymphaeum. Note the hypothetical course of the aqueduct in the upper part. / From Scrinari-Ricciardi 1996, I, fig. 180.

Originally published by “Ostia: Harbour City of Ancient Rome“, republished with permission for educational, non-commercial purposes.