The discursive mode established between students and teacher was stringent and charming.

By Dr. C. Stephen Jaeger

Professor of Germanic Languages and Literatures

Center for Advanced Study

A didactic poem by Hermann of Reichenau offers one remarkable response to the dilemma posed by the education of women in monastic communities. Its exceptional opening section is a skilful, startlingly original, cautionary comedy-drama with a sharp edge against female-male erotic relations, aimed at setting the boundaries of the licit love between a male teacher and his female students. The discursive mode established between students and teacher is stringent, charming – and not without threat. It has a ‘horizontal’ nature: the learning happens by personal, social teacher/students interaction – in this case by thrust and parry, accusation and defence, slander and extreme insult, followed by threshing out the moral truth underlying the issues raised by ludicrous statements.

Women in monastic communities who sought education faced a dilemma. So did their teachers. The dilemma was posed by the institutions and presuppositions of the religious life. The institutions favoured with near exclusivity the education of men by men. A strict separation of men and women was enjoined in Church law and realized in practice since Carolingian times. Greater or lesser adherence to that arrangement is dominant throughout the Middle Ages.1 The community of Admont, Styria, Austria can stand as one case of strict separation among many. Founded as an exclusively male community in 1075, the house added a female community in the second decade of the twelfth century. The nuns were shut off from the monks by a wall with one window, through which the nuns received the preaching of monks, and by a door secured by three locks, their three keys in the possession of the abbess and two monks. It would be hard to conceive worse circumstances for receiving either preaching or instruction in the liberal arts. A fire in 1152 that destroyed much of the building nearly consumed the nuns because the two key-keeping monks could not be found. The door was broken down; the wind shifted; the nuns were saved. The relief at their rescue was somewhat mitigated by the anxiety consequent on the removal of the barriers between the men and the women.2

The presupposition that formed the second factor in the dilemma of men and women together was the threat, fear, and assumption of the dangers of amorous or sexual contact or both. A shared life and the simple pleasure of conversing together without strict barriers created potential for trouble – or, rather, was itself trouble. The experience of Robert of Arbrissel is a good illustration. He had to be sternly admonished, once by a bishop and once by an abbot, not to allow men and women to sleep alongside each other in the new foundation of Fontevrault. For Robert, the sleeping arrangement was a test to show angelic restraint. Abbot Geoffrey of Vendôme calls the practice ‘a new and fruitless form of martyrdom’. ‘It must stop’, the abbot commands: Robert may not speak privately with women and may not show himself ‘charming in speech or eager in his service’.3 Cohabitation in any form could rouse suspicion. Recall that Peter Abelard as the founder of the order of the Paraclete was accused of lewd intentions in his interactions with the nuns years after his castration.4

Whatever barriers limited the common society of men and women religious in the life of learning, men taught women, and in communities where nuns valued and sought learning, close contact of men with women was unavoidable.5 The common life of men and women in monasteries, says Christina Lutter, ‘is exactly where the danger for the spiritual virtue of virginity lies. It is therefore not surprising that the subject of how men and women could and should live together and at the same time be protected from one another was one of the “hot topics” of contemporary discussions’.6 The topic of this essay sits precisely in that crux.

In the century between 1050 and 1150, women’s communities alongside men’s grew at a rate that had not been seen previously in Christian coenobitic life.7 The education of women grew with them. The inevitable barriers were overcome somehow. The history of that overcoming is still to be written. Its historical sources are opening to view after long obscurity.

Alison Beach’s studies of nuns as scribes have made clear that nuns’ learning has been badly underestimated. At Admont, women played a very active role not just in copying texts but also in producing commentary and in writing and delivering sermons. The nuns in Beach’s studies pestered their magistra for instruction in poetry and prose so much that she often worked at night to keep up with the demand.8

The historical sources that might give us details and close focus on women’s education from the tenth century to the twelfth are scant and random. But what happened beneath the horizon of historical scrutiny happened nonetheless. We must hope for enough chance glimpses at the processes to reconstruct what was an important trend in the intellectual life of the tenth and eleventh centuries.

In the German monastery of Lippoldsberg, in the mid-twelfth century, the provost Gunther built up the library and the intellectual climate of the house in close cooperation with the prioress, Margaret. This cooperation is commemorated in the dedicatory image of a Gospel book commissioned by Gunther. The illustration (Fig. 2) shows Gunther and a female figure, presumably Margaret, standing at the feet of the much larger figure of the monastery’s patron, Saint George. Their right hands are joined. At each corner is a praying figure, three nuns and one cleric. Julie Hotchin’s study, Women’s Reading and Monastic Reform,9 takes this image to represent the cooperation of provost and spiritual director as members of the community look on with gestures of thanks and prayers directed to the monastery’s patron, the central figure, dominating by his size. The context of the illumination points to the growth of the library and the cultivation of learning that had begun with Gunther’s arrival at the monastery some twenty years prior to the commissioning of the book around 1160.

But the composition sends a distinct message that comments on the relationship of provost and prioress by evoking a marriage ceremony. Gunther’s right hand offers an object to Margaret. It is not clear what it is: an orb? an apple? a Mass wafer?10 Margaret receives the offering; in fact, her reach overshoots the object so that her hand seems to caress Gunther’s wrist. The gesture is an instance of the iunctio dextrarum, firmly associated with the ceremony of marriage.11 The patron is positioned as the presider in the wedding ceremony. The clear statement is that Saint George joins them in a spiritual marriage. This interpretation is firmed up by the scroll dependent from the patron’s right wrist: ‘I join you in true peace through the worship of God’ (‘Vos pietate Dei iunga(m) vere requiei’). The gesture of Gunther’s left hand seems adversative to that primary context: raised, palm forward, it looks like a gesture of warding off, decidedly not suited to expressing love and friendship.12 Possibly the message of the left hand checks that of the right. The relative position of the arms strengthens that reading, since Gunther’s is fully extended, while Margaret’s is slightly bent. With whatever intent, she is held literally at arm’s length. But apart from a stated or implied comment on their relationship, the overarching context is teaching and reading as a shared intellectual activity of men and women.

Reading this joining of right hands as a gesture of spiritual friendship would be consistent with a fundamental feature of educational practice in the period: the master-student relationship is grounded in love and friendship. That relationship had been an element of aristocratic education since Antiquity, as fundamental to education as is shared intellectual curiosity now. Quintilian had written,

Pupils should love their teachers as they do their studies […] This feeling of affection is a great aid to study, since students listen gladly, believe what they [beloved teachers] say, long to be like them […] and seek to win their master’s affection by the devotion with which they pursue their studies.13

A letter of Adam of Perseigne (d. 1221) lists the six conditions for successful instruction of novices. The last two are ‘tender solicitude towards his novices’ and ‘friendly and frequent conversations with them’.14 The education of Guibert of Nogent is a case where the medium of love overrides motives of pure learning, knowledge, skills, etc. His master lacked learning, intelligence, and common sense, but the love of his student was the basis of an education for which the recipient was exuberantly grateful.15 Love alone, absent intellectual competence, resulted in a satisfactory education.

But in the case of monks or clerics teaching nuns, this element of education – the mutual love of teacher and student – further complicates the vexed question of how nuns and monks speak to each other and, more generally, how they govern their interactions. The incentive to teach and learn in the medium of love is considerable, but it pushes against the hedges on a shared intellectual life of men and women. Teaching and learning without love and friendship has to appear as sterile as in the modern world learning without shared intellectual passion. And yet, are not the language and gestures of love, passing between teacher and student, a temptation in themselves, if not quite at the same level as sharing the same bed?

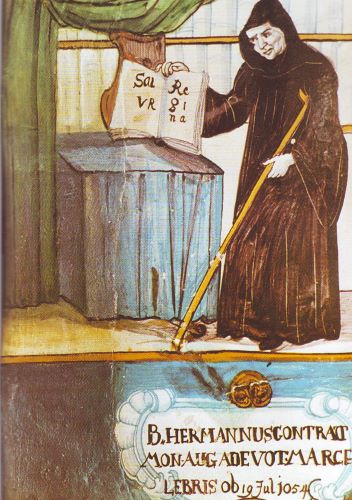

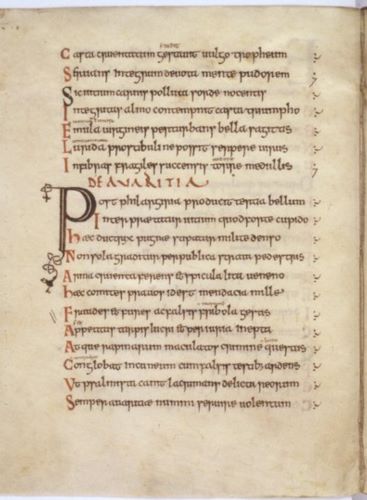

A didactic poem by Hermann of Reichenau (d. 1054) opens to view one remarkable response to the dilemma. Hermann was one of the most learned men of the early eleventh century. He is best known for his writings on the astrolabe and on music, but he also wrote a poem of 1722 lines on the theme of Contemptus mundi, composed 1044-1046. The first third of the poem, 492 lines long, forms a prelude to the more conventional sermonizing of the second part, focused on sin and damnation.16 Hermann planned a third part treating redemption, but the work remained unfinished. Given the two parts that remain, we can surmise that the poem, if completed, would run some 3000 lines. The work is little known and little studied. A recent dissertation by Hannah Williams, not yet published, may help revive interest.17 Williams includes the full Latin text and an English translation. A German translation by Bernhard Hollick also has appeared recently (2016).18 A passage in the brief biography of Hermann by his student Berthold of Reichenau conveys what the poem meant to its author. Berthold tells of a dream Hermann had on his deathbed. In this ‘ecstatic vision’ (in extasi quadam raptus) he saw himself feverishly reciting out loud, from memory (‘the way we recite the Lord’s Prayer’) and rereading two works: Cicero’s Hortensius and his own De octo vitiis principalibus. In his dream, the poem was complete.19 The context gives a clear indication of the importance of this work for Hermann: it occupies his thoughts and dreams in the moments prior to his leave-taking from earthly life; it is mentioned in the same breath with the pagan work that had turned the young Augustine on the path to philosophy and to Scripture; he sees himself reciting both works as he might recite the Lord’s Prayer.20

A close familiarity with eleventh-century poetry will turn up a number of remarkable, not to say amazing, works of poetry created in the period and, just as powerfully, will show how little attention modern scholars have paid to them. The opening section of Hermann’s poem is one of the strangest works of original genius known to me from the Middle Ages. I will call it ‘the prelude’, but I stress that it is nearly one-third of the entire poem as received. Knowledge of poetics, rhetoric, topoi, all the apparatus of convention with which we approach medieval poems, will help on the margins but do not touch the heart of this strange poem. Two recent commentators give hardly any idea of its flavour.21 It is to the credit of Hannah Williams that her dissertation and her article ‘Taming the Muse’ give clearer definition to the character of this introductory fantasy.22 The prelude opens up a unique view of the tenor of student-teacher interaction at a monastic ‘school’, with implications for male-female pedagogic relations more broadly and also with implications for horizontal learning. We can think of the prelude as the setting of an instructional scene, the classroom being prepared for the lesson, the students ‘tuned’ to the instruction. This ‘preluding’ is then followed by the sermonizing part, the lesson on the seven principle vices. The first dramatically shapes the relationship between teacher and student (horizontal); the second discourses on issues of morality (vertical).

The prelude is a dramatic dialogue – or, rather trialogue – between Hermann, his muse Melpomene, muse of poetry, and the nuns to whom the poem is addressed. The situation is: Hermann summons his own private muse, whom he treats as a familiar and serving spirit, and sends her to an unnamed community of nuns to sing soothing songs to them. Melpomene appears, bringing songs, apologizing for her hoarse, unpractised voice. ‘What shall I sing?’ she asks. Hermann: ‘Darling one, you to whom my devotion is greatest, I really don’t know what those little ladies (dominellae) might want to hear. They often like frivolous things (ludicra); they do not prefer serious ones. Ask them yourself ’.23

The muse then addresses the sisters: ‘Oh chaste, lovely company and beautiful gathering, Our little friend, little Hermann (amiculus, Herimannulus) sends me to you … Shall I sing serious things? If not, then I’ll sing comic ones (ludia – stage appropriate)’.24 The sisters’ answer lurches from cordiality to salacious insult:

You are a beautiful and charming lute player

and certainly a worthy young woman to him,

but alas! Unknown to us up till now.25

Come! Tell us first of all, we beg you,

what business he might have with you!

For the attractiveness of your face is startling.

Perhaps you are the partner of his bed

stealthily snatching the dutiful embrace of a sweet kiss,

things one dares do only in the silence of the night,

harvesting joys denied to us.

Maybe this man whom we take to be purer in body than glass,

more chaste and loyal than the turtle-dove,

this perfidious man, exhausts his leisure hours

with you, oh young lady?26

Williams reads the lines as an accusation that Hermann is too preoccupied with secular poetry, answering the implied charge that the nuns have neglected the gifts of Melpomene,27 but the narrative impact is certainly in the fanciful charge of lewd dealings, that Hermann is, to put it colloquially, in bed with the muse.

She responds indignantly to this provocation: ‘I thought you knew who I was, especially the first among you, Engila. I and my eight sisters are the ancient muses, now converted to Christianity’. She continues:

By now we are recognized as worshipers of Christ, and

We love those who are chaste, cultivators of the mind,

And by teaching holy things we urge them to follow the right path.

And sometimes we can compose honourable jokes

If asked; but we perform lewd things

Only if our faithful friend asks it.He would know the honest way to mask dubious stuff,

Not subjecting the most intimate parts of the mind to a lascivious word, while

Christ the judge looks from heaven attentively on all things.28

While the subtext opposing the classical tradition (lewd) to Christian (pure and decent) is played through here, the muse now confronts head-on the nuns’ insinuating suggestion of lasciviousness. Stung, she turns on them. [I paraphrase, in italics]: Your suspicion of Hermann and me shows that you envy the ‘forbidden pleasures’ we supposedly share. We pardon you for even thinking it. You resent it that we do not include you in a ‘sweet alliance’ (foedere suavi) to partake with us in those illicit embraces.29

A sharp thrust home by the muse: only someone who desires forbidden pleasures could make such accusations. And here the language is laced with hooks and barbs: Only guilty persons would hurl such an accusation. Perhaps what you have charged me with is what Hermann thinks of you, that you enjoy lascivious pleasures. Perhaps he is too shy to make such accusations, but while he may think it, he knows in his heart that he loves you; such distrust does not breed hate. He wants you pure and chaste for the heavenly bridegroom. But he has heard rumours that the mind of woman is inconstant, unstable, easily seduced, and he fears that you might prefer the loathsome pleasures of the night to that heavenly marriage.30

The muse continues at length in a flood of invective, indicting sexual pleasure as disgusting and obscene. She checks herself: I have not come for such railing, but rather ‘to soothe you sweetly by various odes with notes rising graceful from the throat and shaped in the mouth, … and to compose something for you … which shall henceforth render you mindful of your friend’.31

The sisters answer: ‘Oh venerable young woman, cagey (cata), learned, beautiful and lovely, chaste and dear sister, sure friend of Herman’: You’re being too hard on us and your language is really harsh. You’re hiding the fact that it’s really Hermann himself who has said these things. This is his style: to make a joke out of this sort of admonition and to make jokes while railing with a sharp tongue against vice. [We’ll come back to this series of comments on the pedagogy of joking]. You’re trying to bring out any secrets hidden in our hearts by this speech – but we’re onto your subtle strategy: anyone who shuns hearing vices mocked with biting speech reveals vices lurking in herself.32

Then follows, again, the question, what song she should sing. The Muse now addresses Hermann: Your sisters, who love you dearly, want to know what you would like sung to them. They would like you to put aside jokes and sing sentiments pleasing to you.33

Rather than answering, Hermann calls the muse to account: What took you so long? Why are you returning so late? And you’re still asking what to sing.34 The Muse answers: We had a long conversation; we exchanged jokes and laughter. I answered their frivolous speech as was appropriate. What dullard would hear facetious, insulting speech without responding in kind? They made jocular comments about you and me sharing sweet crimes. I gave them back as good as I got. I met their false suspicions with some of my own. I said, we suspected that they were enjoying obscene, evil, frivolous love affairs. I spoke in pleasant jest, but didn’t shrink from harsh words. If they are offended, it could only be because they are in fact guilty as insinuated.35

These comments rouse Hermann’s anger at the Muse: I fear that you might have offended these loyal, honest, sweet-speaking friends. Your duty was to make our friendship closer by singing sweet sounding odes. I hope you haven’t offended them to the point where they no longer love me/us. And here suddenly he turns nasty: Why did I ever send you to them, ‘you dog, who have bitten them with your merciless teeth. Until now they were firm as rock [in loyalty and friendship]. Now you have angered them and made me lose the loviness (amorculum) I’m used to receive from them’.36

The Muse, her own anger rising: Are you kidding? Or are you crazy? (Ludis, insanisne?) I spoke the truth, and you, you dimwit (stupidus), fear that I’ve irritated your loveable sisters? Your foolish complaints must indicate there is some truth in their accusations. And isn’t it you who are questioning their morals by believing they might be offended by my admonitions? And what an accusation you make against them! You’re implying that they might be so taken with shameless lecher y as to forget all the pains of punishment for licentiousness: [now I’m translating the list of pains]:

The rebukes of the shocked public? The scourging from your judges? Whipping? The pain and shame of giving birth? The great danger of imminent death? Fear for your newborn baby; the need to hide the child? The terrors of hell waiting eagerly with its tortures? The laughter of demons and of Satan goading them on to torments? Finally, the lamentation of your heavenly bridegroom Christ, of all angels and citizens of heaven, keening sad laments at your deed of shame?37

Then follows, in still more lurid tones, a depiction of the sex act – not love at all, but rape by some brute driven mad by lust.38

Shame on you, says the Muse to Hermannn, for even thinking the sisters capable of such laxness of mind. And don’t take offense that I depict such shamefulness: it may be crude, but it’s true. So, trust them, give them credit: they would not hate you for being told things they know to be true. You yourself often decry vice amid jesting and laughter. Because of what I’ve said they will love you even more deeply. So drop your foolish complaints and tell me what to sing.39

Hermann’s lengthy response, here much shortened: I admit, you speak the truth, o Muse, even if you’ve gone too far by pressing the truth in this hard and biting tone. Now leave off ludicrous things; sing something serious and useful (see lines 375-410).

The last 82 lines are given to more talk of what she should sing. The tone of irreverent banter alternating with invective fades. Melpomene then launches into the body of the poem, composed in elegiacs, until the final exchange of thanks and farewell between the Muse and her audience, the sisters. The rest is of little interest for our topic, because the learning reverts to ‘vertical’ and loses the striking ‘horizontality’ of the prelude.

The community of nuns addressed is nowhere identif ied in the poem, nor has a possible source been identif ied in religious communities around Reichenau in the early eleventh century.40 The best conjecture is Buchau and Lindau, long-standing convents of canonesses. The name ‘Engila’ is prominently mentioned in Hermann’s poem. She is to be ‘first among the sisters’,41 but the reference does not make clear whether she is their teacher, prioress, or abbess. The name is no help in locating Engila or her nuns historically.42

It is worth mentioning that in the same years Hermann worked on his poem, the abbess of Zurich, Irmingard, was removed from her position for sexual transgressions. Nothing else connects Hermann and his poem directly with this scandal, but it must have been well known in Reichenau. Hermann’s abbot, Bern of Reichenau, wrote a letter to Henry III depicting Irmingard’s sins in vivid colours and asking the emperor to show mercy and forgiveness.43 Written in late 1044, it coincides with the time of composition of De octo vitiis.

It has been conjectured that the teaching dialogue might be a f ictional frame; that the work was basically addressed to men and that the address to women is a poetic conceit. It may hold true of the body of the text, which speaks variously to nuns, monks, and clerics. But the prelude explicitly addresses a community of religious women.44 The stronger argument seems to be to accept the text as it presents itself: a beloved teacher composes a collection of poems to give a community of nuns instruction in poetics and morality, though the body of the work is pitched more broadly. Sending the composition via the muse is a convenient conceit. It creates a space to say things he clearly wants placed in the mouth of a third party. The whole complex tissue of ironic jesting, teasing, and taunting in the prelude has so f irm a dialogic and psychological reality that it seems unlikely to be framed for an audience of the other gender – with what motive? So that the ‘real’ audience of men can enjoy some high-spirited off-colour banter? The cattiness of women in love relations is at issue in the prelude certainly, possibly a subject for male edif ication, if a tasteless one, but what fear would be roused in men and what lesson taught by evoking the pains and dangers of childbirth and the anxiety of concealing (getting rid of?) an unwanted child? The prelude is almost certainly a skilful, startlingly original, cautionary comedy-drama with a sharp edge against female-male erotic relations.

However, it should be said that Hermann the Lame, the Cripple, has cast himself in a strange role: a man taunted with charges of lasciviousness and sexual relations with the muse. His biographer tells us that from youth on, his body was hardly usable for walking or talking; he had to be carried in a sedan chair.45 So it seems unlikely that he would appear, even in the imagination of loving students, fit for country matters. I doubt that the audience for this poem would have missed the dark, ironic reverberation in the nuns’ praise of his chaste body: ille vitro corpore purior (54).

Out of the abundance of topics this long prelude offers, I will focus on three subjects important for understanding the form of learning at work here: poetics, the cult of love and friendship in teaching, and jest and earnest.

Poetics, the first, has been hardly mentioned until now. The entire work is a series of poems, and the metre changes with each change of speakers. The author himself has designated the verse form that follows, and the designations inject a decidedly pedantic tone into the otherwise impassioned temper of the exchanges. No single verse form repeats. Variety in metrical forms is clearly a goal of the poet.46 In this the poem is similar to Dudo of Saint Quentin’s De gestis Normannorum, a prosimetrical history-epic (996/1015) unmatched by any other medieval poem for the range of its metrical forms. Hermann offers twenty different metres. The pedagogic intent is underscored in scholia in the unique complete manuscript commenting on the metrics, probably by Hermann himself.47

Hermann makes the remarkable statement that poetry is the subject he cultivates most devotedly (mi maxima cura; 17). A serious confession, or a posture modelling commitment to poetry for the benefit of the nuns? The evidence argues for taking the claim seriously. His deathbed vision had him reading his own poem, imagined as complete, alongside Cicero’s Hortensius. Throughout the prelude his admiration of classical Latin poetry is evident. Place these internal indications alongside the high stature of poetry in the schools of the period, and the claim is not improbable.48 It should encourage scholarship on Hermann to consider the prime importance Hermann himself assigned to poetry in his oeuvre.

This virtual textbook of poetic forms is accompanied by implied reproaches for the nuns’ neglect of poetry: Melpomene is surprised that they do not know who she is. She would have thought at least Engila knew the muse of poetry. Melpomene and her eight sisters love chaste women and those who cultivate the mind: Mentis cultores semper amantes (76). The nuns are prodded to become familiar with the muse and be or become mentis cultores. The eleventh century saw a remarkable blossoming of women’s poetry, among both nuns and seculars, though the actual creations surviving are few.49 Evidently Hermann’s ‘little ladies’ wished or at least were offered the opportunity to participate in that trend.

An important element of the social climate of teacher-student relations is apparent in the mode of interaction posited in this poem: friendship and love are the norm of relationships, their default setting. All parties to the trialogue of the prelude speak a sweetened, sentimentalized language of love. The muse is Hermann’s ‘beloved’ (dilecta; line 1), his ‘dear’ one (cara); the nuns are his ‘dears’ (caras), his little sisters (sororculas), ‘little ladies’ (dominellae). The muse answers Hermann’s call: ‘Have I drunk in with my ears that my friend Hermann calls me?’50 He is her ‘beloved brother’ (frater amate). The sisters return this language. Facing the muse and questioning her for the first time, they begin with protestations of undying love for Hermann: ‘Is it our very own dear liebling Hermannlet, / who is seared deeply in our innards / beloved through all time, / who has sent you?’51 The persistent use of diminutives makes the tone maternal, softly affectionate, and intimate, as if the language were that of prose lullabies. The sisters’ first response to the muse: dear little Hermann (liup Herimanulus) is their little friend (amiculus). Mixing a German term of endearment (liup) with the relatively sophisticated, learned Latin, gives the phrase a flavour of home-spun familiarity.52 Hermann fears that the muse’s harsh words accusing the nuns will cost him the ‘loviness’ (amorculum; 301) to which he has become accustomed. That is a short list of diminutive terms from the first few exchanges. It could easily be doubled.

The exchange swerves abruptly into barbed comments. They notice the beauty of the muse, which is so great that it startles them. As if seized with sudden jealousy, they launch into the first wave of abusive suggestions: ‘Do you embrace him in bed, enjoy his sweet kiss and indulge in the forbidden pleasures of the night?’ The insinuation is a breach of friendship, and the Muse answers at once with a stinging and salacious taunt: ‘what troubles you is that you are not included in that “sweet alliance” (suave foedus) that your imagination has dreamed up. You’re jealous of those forbidden pleasures you imagine us sharing’. The important point is that the sardonic and snide elements in each exchange (and all three are guilty of them) get corrected back to the norm of friendship; even though they depart from that ideal a long way, reconciliation is always the outcome of exchanges. In the first exchange that swings from friendly to nasty, Hermann intercedes, chiding the Muse for possibly offending the nuns. He gets angry at her, calls her a dog, and accuses her of destroying his good relationship with the nuns. She responds, outraged: he is either joking or insane. She calls him ‘stupid’. She explains with arch subtlety that it is his anger that casts serious aspersions on the nuns’ integrity.53 It may well indicate to them that there is truth in their accusation of illicit relations between Hermann and her. His anticipating their anger also implies his own guilt and a callous forgetfulness of the horrible consequences of lust. ‘Probably, she concludes, they will love you more for receiving the lessons I’ve given them in the form of provocative jesting’ (see 302-365), and she conjures the repair of the bond among them: ‘you yourself remain bonded to true friends with a singular steady love, having thus far been held in adulation and henceforth to be loved’.54

Hermann agrees. And so this nastiest and crudest of exchanged barbs ends also in reconciliation and the promise of the return of a friendship that is only tested and strengthened by empty accusations. There is a ius amicitiae at work in the ‘classroom’ of this poem, and a basic narrative dynamic is the positing of this law, the violation, and the return to it.

Another element of the prelude is the alternation of jest and earnest, both in the content of the exchanges themselves and expressly addressed in the discussions of the participants. E.R. Curtius included an excursus on ‘Jest and Earnest’ in his great study of European Literature and the Latin Middle Ages.55 Inevitably, commentators on Hermann’s poem have cited Curtius to show its indebtedness to a topic of rhetoric from the ancient world. As so often, the authority of Curtius short-circuits attempts to locate poetic statements in a contemporary social context. In this case we do well to resist Curtius. Hermann’s poem offers a distinct example of horizontal learning, the rhetorical fashioning of a classroom atmosphere. The learning happens not by the transmission of learned material and the citing of topoi (though that will be part of the lesson in the didactic part of the poem that follows) but by personal, social interaction of the teacher and students among themselves – in this case by thrust and parry, accusation and defence, slander and extreme insult, followed by threshing out the moral truth underlying the issues raised by ludicrous statements.

In helping the Muse work out the subject of her songs, Hermann reveals some of his own pedagogic techniques. The choice of a song turns on the opposition of jest and earnest. He notes his students’ preference for ‘comic things’ above ‘serious ones.’56 The Muse puts the choice to the nuns: ‘If you wish, I will sing serious things; if not I shall be a comic singer’.57 The muse opens to view a pedagogic strategy underlying this choice:

While we [muses] love cultivators of the mind, we can also now and then mix in decent jokes, if asked. We shun anything indecent, unless asked by our faithful friend (Hermann), who knows how to mask indecent things decorously so as not to subject the inner chambers of the mind to lascivious speech.58

This is odd praise, somewhat illumined when the sisters reveal the play of jest and earnest as a pedagogic strategy of Hermann. They react to the Muse’s blunt innuendo by suggesting that Hermann is speaking through her: ‘It is his custom to clothe such admonitions in a joking tone when speaking to his [students, people], and to jokingly give focus to some vice in a sharp, biting tone’.59 The pedagogic jibe is related to the strategy indicated earlier by the Muse to the sisters: ‘We hesitate to perform base subjects unless our faithful friend should ask. He knows how to mask dubious stuff to make it decent, so that the most intimate parts of the mind will not be subjected to lascivious speech’ (n. 58 above). And again, ‘Haven’t you yourself often decried vice with a sharp and biting joke?’60

These passages support my thesis that this poem opens a perspective onto the classroom of Hermann of Reichenau, at least an imagined classroom situation. He reveals a peculiar teaching strategy, in which even harsh and nasty accusations become good pedagogy. If any reader is inclined to think a monastic school a rigidly earnest, priggishly pious institution, a reading of Hermann is warmly recommended as an antidote. It is possible to combine moral rigor with jocular familiarity. If Hermann’s ‘classroom’ is exemplary, we can imagine monastic education as stringently demanding, and a lot of fun.

A parallel example from a teacher of a preceding generation, Froumund of Tegernsee, sheds light on Hermann’s poem. Froumund (d. 1008), schoolmaster in the Bavarian monastery of Tegernsee, wrote a poem to his students that gives us a vivid look into his schoolroom. He chides them, with lots of wit, verve, and posed outrage, for preferring play-acting and showy but shallow entertainments to poetic composition.61 Their Abbot Pernger has faulted them for never offering him so much as a line of verse. Froumund’s poem is a response, dedicated to the abbot and urging the others to compose verse and send it to Abbot Pernger so as to ‘drive the anger from his mind’.62 He laments that his teaching has accomplished nothing, high though his standards were:

My words might be harsh, but in my heart I love you. Are all my efforts wasted, all my labor lost? […] If I were to take somersaults and pratfalls, if I would play a wolf or bear or fox […] if I composed fables, as Orpheus regaining Eurydice with his song […] he nearest me in plainest sight would rejoice, and all the boys would shake with lewd laughter […] The one who speaks the truth is less to you than a flapping shoe-tongue. Just look at the way you prefer jokes to composition. I have decided that it is better to play-act (ludere) in poems that enlarge the soul and the mind […] Come brothers, let us compete now to make a metrical song!63

This poem has some of the elements of Hermann’s poem: alternation of harshness and love (‘I love you though I speak hard words’); criticism by ridicule, aimed at provoking the students to perform; and the opposition of ludicrous to serious subject matter. In Froumund’s classroom there is an express element of theatricality: the boorish play-acting his students hope for from their teacher, and the higher ‘ludic’ element of the high-toned poems Froumund calls for. Levity is not banished from the classroom; far from it. Hermann’s poem aims to combine the high-toned with entertainment that occasionally veers in the direction of an off-colour Punch and Judy show. And in both cases, these antinomies are resolved; with Froumund a compromise: he decides ‘play-acting’ (ludere) is fine, but only in the composition of poems that elevate the mind and increase genius (‘carmina que faciunt animum crescere et ingenium’), i.e., jest combined with high sentiments. With Hermann the thrust and parry of ludic and earnest ends with the earnest being given priority, and that tone dominates in the main body of the De octo vitiis that follows the prelude. (‘Utile canta, casta camena, / ludicra respue, seria prome’; lines 388-389). His biographer, Berthold, however, is unquestionably characterizing the prelude more than the preaching part of De octo vitiis when he calls the work a libellum iocundulum – getting in two more diminutives – ‘a cheery little book’.64

The tone of this unusual comedy-drama of alienation and reconciliation, of offense given and offense returned, ending in docility and love, results from Hermann’s double obligation: to maintain love and friendship with his students on the one hand; and to castigate female desire and sexuality with powerful rhetoric on the other. An important distinction between these two ‘classrooms’ for our purpose is the lack of any hint of sexual taunting in Froumund’s verses and the prominence of sexual taunts in Hermann’s. The coarse elements in Hermann’s poem, I believe, are connected with the problem sketched above of men and women together in the life of the schools. The mutual sexual taunting is a rhetorical shield; its purpose is comparable to the raised left hand and arm’s length by which Gunther of Lippoldsberg distances himself from Prioress Margaret (see above), joining them in spir-itual marriage but setting clear limits. Its purpose bears comparison with the wall and thrice-locked door at Admont: take down the wall, and other means – discursive means – become the protective wall, more permeable but more humane and of greater moral strength. Those means still imply or suggest a threatening sexuality emanating from the women that men must ward off. Hermann alienates his students (or risks it) in order to wall off that threat and to establish licit love and a harmonious teaching relationship with them. In doing so he also establishes a discursive mode between students and teacher that is stringent, charming, and not without threat.

It would be hard to name a didactic poem by a medieval monk and scholar in any way comparable to this strange dialogue whose tone shifts from lightweight comic bantering to angry insults, passing through innuendo and obscenity, and funnelling into austere didactic exposition (the discourse on vices). It brims with personality and a wit versed in the art of rousing or restoring friendship by starting with insult and provocation. It revels in ironic posturing, a form of behaviour known and practiced in the Middle Ages called facetia. Its remarkable tone and the whole ethos of the prelude fit the personality of Hermann as described by his biographer:

[In spite of his physical impairment] to his auditors he was an eloquent and eager teacher, revelling happily in liveliness and energy. He showed great alacrity in disputation and seldom failed to answer each query with a courteous response […] Forthright but not quarrelsome, he regarded nothing human as alien to him […] He cultivated compassion with a bright, cheerful spirit […] He strove for a marvelous kindness and affability, good humour and humane empathy, showed himself a model of decency and adeptness to all, and, being made all things to all men, he was loved by all.65

A comment by Ernst Dümmler, passed on by Manitius and now again by me, captures the sense of an energized and humanized asceticism evoked in Berthold’s affectionate eulogy: ‘The poet Hermann gives us a profound view into a soul which may have died to the world, but was very much alive to it’.66

Endnotes

- See Griffiths and Hotchin, ‘Introduction’, 1-45.

- Following Alison Beach, Women as Scribes, 68-9.

- Cited and discussed in Jaeger, Ennobling Love, 129-30.

- Abelard, Historia calamitatum, chap. 65, 102-105.

- Admont differed from other communities by receiving in mid-century a magistra who had received from youth an education from Salzburg clerics. Vita, ut videtur, cuiusdam magistrae monialium Admuntensium, chap. 2, 362: ‘Ex illustrissimis Salzpurgensis ecclesiae ministris oriunda exstitit, ibique in superiori castro eiusdem urbis educata’. So she had men in her educational past outside of the frame of the monastic life. She was highly educated in the liberal arts, second to none, her biographer claims. She composed and taught composition in prose and verse, and was so in demand that she received calls to travel elsewhere to dispense her teaching. See commentary in Beach, Women as Scribes, pp. 69-70. Also Lutter, ‘Christ’s Educated Brides,’ 197-201.

- Lutter, ‘Christ’s Educated Brides,’ 201.

- Griffiths and Hotchin, ‘Introduction’. Also Lutter, ‘Brides,’ 193-4.

- Beach, Women as Scribes, 68-72.

- Hotchin, ‘Womens’ Reading,’ 139-174.

- The entry on this image in the Index of Christian Art identifies the object, mysteriously, as a roll. See the entry under Kassel Lib., Hessische Landesbibliothek, Theol. Fol. 59.

- My thanks to Jeffrey Hamburger for this reference. Prominently studied for ancient Rome, the iconography of marriage called on this gesture into the seventeenth century. See Yang, ‘Trusting Hands’.

- The range of meaning of the gesture is wide. It is common in annunciation scenes, where the Virgin raises her hand in astonishment, or possibly self-protection, at the message of the angel. But it also occurs in the context of teaching, and once, though in a much later image, in the context of Friendship personified opposed, or warded off, by Hate. British Library Add. 28162.

- Quintilian, Orator’s Education, book 2, chap. 9, 323-325.

- Long, ‘Entre spiritualité monastique et canoniale,’ 255, citing Adam of Perseigne, Epistola 5, 118 : ‘Nascitur etiam ex amica frequenti et honesta collocutione commendabilis queque familiaritas, per quam magister efficitur ad corripiendum audacior, correptus ad disciplinam patientior, uterque ad intelligentiam Scripturarum eruditior’.

- Discussed in Jaeger, Ennobling Love, 64-65.

- See Berschin’s comments, Berthold of Reichenau, Vita Herimanni, 24.

- Williams, Authority and Pedagogy, and her article ‘Taming the Muse’.

- Hermann of Reichenau, Opusculum Herimanni (De octo vitiis principalibus).

- The standard text of Berthold of Reichenau‘s Chronicon is Die Chroniken Bertholds von Reichenau und Bernolds von St. Blasien 1054-1100, edited by Ian Stuart Robinson. I quote from Berschin, Hermann der Lahme, who prints the entire section on Hermann (6-13), with a German translation. Hermann’s dream as conveyed by Berthold is the point of departure for Williams’s study, Authority and Pedagogy, 10-13.

- Berthold of Reichenau, Vita Herimanni, 10.

- Berschin, Hermann der Lahme and Bernhard Hollick in his edition mentioned above: Hermann of Reichenau, Opusculum Herimanni (De octo vitiis principalibus).

- Williams, ‘Taming the Muse’, 130-143. Williams recognizes the wit and sardonicism of the prelude, but she interprets the striking intermingling of classical with Christian poetry in terms of poetics and poetic practice. She also wonders whether the nuns were the real recipients or just a fictional invention. The former seems to me the more likely. The clear intent of the prelude is the harmonizing of an intellectual community, that is, an unconventional form of horizontal learning. Seeing the nuns addressed as pure fiction in a work about poetry and morals directed to men makes the learning strictly vertical, a product of intellectual teaching.

- Hermann of Reichenau, Opusculum Herimanni Diverso Metro Conpositum, lines 14-24: ‘[MUSA:] Dic modo, quae vis / Psallier ollis! / [HERIMANNUS:] Certe nescio, cara / et mi maxima cura, quid cantarier illae / affectent dominellae. / Novi, ludicra crebro, / malunt seria raro. / Ipsas tu magis ipsa / pergens consule, musa’. I lean on Williams’s translation but adapt freely.

- Lines 26-39: ‘[MUSA:] Vos, o contio candida / Ac formosa catervula! / Noster misit amiculus / Communis Herimannulus / Me promptam sibi psaltriam, / Quamvis pessime raucidam, / Vobis gliceriis suis / Electisque sororculis / Quaedam carmina pangere, / Sed vos qualia dicite! / Nam vos quaeque libentius / Auditis, cano promptius: / Vultis, concino seria, / Sin, cantrix ero ludia’.

- The line nobis heu tamen hactenus ignota is a confession that they have neglected classical poetry, as Williams argues in ‘The Taming of the Muse’.

- Lines 44-57: ‘Formosa namque es bellaque psaltria / Illique certe digna iuvencula. / Sed ipse nobis heu tamen hactenus/ Ignota, primo dic age, quesemus, / Tecum quid illi forte negotii! / Vultus venustas terret enim tui. / Tu forsan eius conscia lectuli / Complexa dulcis munia savii, / Furare, noctis ausa silentia, / Nobis negata sumere gaudia. / Fors ille vitro corpore purior/Putatus, ille turture castior / Fideliorque perf idus, a, sua / Tecum, o puella, conteret otia.’ Conteret otiais ambiguous: ‘fills his leisure hours with terrifying things’?

- ‘Taming the Muse’, 138.

- Lines 73-83: ‘Nunc iam christicolae noscimur esse / Suadentesque viam pergere rectam / Castos diligimus, sancta docemus, / Mentis cultores semper amantes, / Interdumque iocos quimus honestos / Pangere, si petimur; turpe veremus / Ludere, ni fidus poscat amicus, / Hoc qui celare norit honeste, / Non ad lascivum intima verbum / Mentis subdendo, iudice Christo / Caelitus attente cuncta vidente’.

- Lines 84-91: ‘Sed quod vos talem suspitionem/In me una et nostrum fertis amicum / Fingitis et turpem nosmet amorem / Noctem furari, nocte foveri / Dulcibus illecebris quodque putatis / Vobis haud fidum gaudia mecum / Illum partiti foedere suavi, / Donamus veniam’.

- Lines 91-110: ‘Conscia forsan / Culpa reos stimulat, insuper attat / Ille vicem vobis reddet in istis. / Nam non dissimilem suspitionem / In vos forte tenet, nec satis audet / Talibus in furtis fidere vobis, / Et tamen interne vos scit amare / Nec quia dif f idit, vos simul odit. / Optat enim castas riteque mundas / Vos casto et mundo vivere sponso / Regalique thoro corpore puro / Dignas felicem cernere lucem / Reginas superae caelitus aulae. / Sed quoniam novit seapeque legit – / Mentem femineam mobile quoddam, / Anceps, fluctivagum, flabile monstrum, / Suspectus metuit perque timescit, / Ne vos postposito lumine tanto / Tamque beatif icis oppido taedis / Spurcida queratis gaudia noctis’.

- Lines 176-183: ‘Non ego veni vobis tanta loqui carmine tali, / Sed vos alternis suaviter odis / Mulcere et gratis gutture neumis / Oreque formatis pangere vobis / Quiddam, quod gracili voceque dulci / Post hinc cantatum seu reboatum / Vos memores vestri reddat amici’.

- Lines 189-212: ‘Veneranda tu puella, / Cata, docta, pulchra, bella, / Soror alma, casta, cara, / Herimanni amica certa, / Nimis arguis misellas, / Nihilum tacendo, nonnas / Neque parcis ipsa amatis, / Veluti fatere nobis, / Heriman ut ipse durus / Videatur haec locutus. / Solet ipse nempe tali / Monitu suis iocari / Velut et iocans acerbo / Vitium notare morsu. / Misera, o, amica nostri, / Rea quae putat notari / Sua conticenda furta, / Tua cum iocantur orsa. / Etenim libenter ista / Capit aure turma nostra, / Quia, quisquis odit acri / Vitiosa dente carpi, / Etiam tacendo prodit, / Vitii quid intus assit.’

- Lines 233-244: ‘Tuae rogant sorores / Te care diligentes, / Quo tu canenda dictes / Mihi et docenda mandes. / Amant enim remissis,/Ut asserunt, iocosis/Audire, quicquid ollis/Plus approbando mittis./Nunc tu tibi placentem / Sententiae tenorem / Des, ipsa quem canendo / Queam iugare rithmo’.

- Lines 245-252: ‘Prius, o mihi grata camena, / Volo, dicas, quae tibi tanta / Fuit illic causa morandi / Tardeque ad me redeundi, / Si nondum, ut forte putavi, / Quae mandaram, cecinisti, / Demum nunc atque reversa / Hic percunctare canenda’.

- Lines 253-278: ‘Haec quid, queso, petis? / Quid ista queris? / Cum me dirigeres ad has sorores / Perlaetas hilarem tui sodalem, / Lusi certe mihi simulque risi, / Par ipsis retuli, iocis rependi / Ludens ipsa vicem. / Quis ad iocantem / Perstaret stupidus nihil locutus? / Cum me teque suum iocose amicum / Culpantes lepide forent adorsae, / Nosmet dulcia confovere furta / Fingentes, precium referre dignum / Ludis mox statui statimque coepi / Fari, nos quod et has tenere cunctas / Suspectas agimur, quod et veremur / Illis spurcidulum, malum, profanum / Furtum, quod miseras necat puellas / Subtractasque Deo pio, supremo / Sponso, illas zabulo dat execrando. / Ridens et licet has darem loquelas, / Nil parcens vitium tamen nefandum / Carpsi dura merum profando verum. / Nil ledens nitidas, pias, pudicas, / Mordebam luteas, lupas, petulcas. / Nostras non tetigi sciensve laesi, / Ni se forte reae, quod absit, ipsae / Tactas dente sciant vel indolescant.’

- Lines 295-301: ‘A! quid queso fuit, quod mea compulit / Vota, ut te cuperem mittere, te canem, / Quae mordax acidis dentibus et feris / Ledens tot socias, quas adamantinas / Dudum credideram forsque putaveram, / Iratas faceres et mihi perderes / Illarum solitum mentis amorculum?’

- Lines 320-334: ‘Verba terrentum, flagra iudicantum, / Ventris instantem gravidi dolorem, / Anxium partum simul et pudendum, / Imminens magnum necis ac periclum, / Curam et ef fusi pueri occulendi, / Perpetes dirae gemitus gehennae/Omnibus poenis et ad haec hiantis, / Doemonum risum, / Satanae cachinnum Ista suadentis, cruciantis ista, / Atque postremo dominantem ab alto / Cuncta cernentem, truciter minantem / Caelitem sponsum dominumque / Christum Eius aeterni preciumque regni, / Angelos omnes superosque cives / Triste merentes facinus videntes’.

- Lines 335-341: ‘Spernere et mecho subici nefasto / Foetido, spurco, tragico / Priapo Turpe rudenti vel adhinnienti, / Eius infando fera cum libido / More se inf lammat simul et catillat, / Quas subans pulcras capiat puellas / Irruat, pungat misereque perdat?’

- Lines 342-369: ‘Absit hoc, absit, procul absit, absit, / Ut tuis caris sociabus istis / Ingeras tantum facinus nefandum, /Quatinus fingas tibi et extimescas / Hoc ob of fensas vel amaricatas, / Quod nefas tantum merito execrandum / Persequor veris nimium loquelis. / Namque si dulces suimet sodales / Ista dicentes odiunt, fatentes / Conscias certe maculas aperte / Proferunt ipsae. Precor unde, parce, / Parce, ne pro his ita suspiceris / Corda prolatis inimica nobis / Sint quod illarum potius piarum. / Crede tu menti bona diligenti, / Quod nimis veras adament loquelas, / Diligant omnes pia commonentes, / Quin magis per se lacerent sputentque / Omne non castum, petulans, pudendum./ Nonne colludens pariterque ridens / Sepe, quae dico, satis haec probando / Ipse tu nosti? Vitiumne acri / Crebro mordacique ioco notasti? / Et tamen castis, puto, non ab ipsis / Flebis abiectus, magis immo amatus / Ipse sinceris remanes amicis / Iunctus unito et amore certo / Usque dilectus et abhinc amandus.’

- Williams locates the broader context for moral instruction of women in the decline of female monasteries following the Ottonian period, but without making a specific identification of the community addressed by Hermann, Authority and Pedagogy, 99-116.

- Lines 59-62: ‘Tibimet, Engila, memet ignotam poteram credere numquam, / nam fert fama loco te fore prim hic inter iuuenes, virgo, sorores’.

- See Williams, Authority and Pedagogy, 109-10; Hollick, Commentary, in Hermann of Reichenau, Opusculum Herimanni (De octo vitiis principalibus), 11 and n. 6.

- Bern of Reichenau, Epistola 27, 61-4. Hollick, Commentary, in Hermann of Reichenau, Opusculum Herimanni (De octo vitiis principalibus), 15.

- Also in the title of the single full manuscript: ‘opusculum Herimanni diverso metro conpositum ad amiculas suas, quasdam sanctimoniales feminas’, cited from Hermann of Reichenau. Opusculum Herimanni Diverso Metro Conpositum, 2.

- Berthold of Reichenau, Vita Herimanni, 6.

- See Williams’s list of metres, Authority and Pedagogy, 124. Also in Hermann of Reichenau, Opusculum Herimanni Diverso Metro Conpositum, 1-2.

- See Hollick, Commentary, in Hermann of Reichenau, Opusculum Herimanni (De octo vitiis principalibus), 30-32.

- On the high stature of poetry in monastic and clerical schools in the eleventh century, see Jaeger, ‘The Stature of the Learned Poet in the Eleventh Century,’ 417-438.

- Dronke, Women Writers, 84-106.

- Lines 4-7: ‘Mene vocari / auribus hausi? / Anne et amicum / mis Herimannum?’

- Lines 40-43: ‘Nosterne, noster ille medullitus / nobis inustus liup Herimannulus, / amandus ille saecla per omnia / transmisit, o , te, pulchra puella?’

- Nicely captured in Williams’s translation, ‘our very own liebling Hermannlet ’.

- Lines 294-301: [HERMANNUS:] ‘Quid fuit, / A, quid, queso, fuit, quod mea compulit / Vota, ut te cuperem mittere, te canem, / Quae mordax acidis dentibus et feris / Ledens tot socias, quas adamantinas / Dudum credideram forsque putaveram, /Iratas faceres et mihi perderes / Illarum solitum mentis amorculum? [MUSA:] Ludis insanisne, quid ista dicis? / Quodque ne veris stupidus vereris / Fatibus dulces tibimet sorores / fecerim infensas? Et ob hoc in istas / Proruis stultas timidus querelas?’

- Lines 366-369: ‘Magis immo amatus / Ipse sinceris remanes amicis / Iunctus unito et amore certo / Usque dilectus et abhinc amandus.’

- Curtius, European Literature, 417-435. On joking and ‘ludic’ elements in poetry, see Bond, ‘Iocus amoris,’ pp. 176ff. Revised and extended in his monograph, The Loving Subject.

- Lines 20-21: ‘Novi, ludicra crebro, Malunt seria raro’.

- Lines 38-39: ‘Vultis, concino seria, / Sin, cantrix ero ludia’.

- 76-82: ‘Mentis cultores semper amantes, / Interdumque iocos quimus honestos / Pangere, si petimur; turpe veremus / Ludere, ni fidus pocat amicus, / Hoc qui celare norit honeste, / Non ad lascivum intima verbum / Mentis subdendo…’

- 199-202: ‘Solet ipse nempe tali / Monitu suis iocari / Velut et iocans acerbo / Vitium notare morsu.’

- 363-4: ‘Vitiumne acri / crebro mordacique ioco notasti?’

- Tegernseer Briefsammlung, 80-83, Carmen 32.

- 81, lines 9-10: ‘Nunc facito versus, omnis, qui scribere nosti, / Ut modo pellatur mentibus ira suis.’

- Lines 30-48, 61, 63-4: ‘Sum mordax verbo, pectore vos sed amo. / Est meus iste labor cassatus, perditus omnis / Et torvis oculis me simul inspicitis? / Si facerem mihi pendentes per cingula causas – / Gesticulans manibus, lubrice stans pedibus, / Si lupus aut ursus, vel vellem f ingere vulpem, / Si larvas facerem furciferis manibus, / Dulcifer aut fabulas nossem componere, menda, / Orpheus ut cantans Euridicen revocat, / Si canerem multos dulci modulamine leudos / undique currentes cum trepidis pedibus,/ Gauderet, mihi qui propior visurus adesset, / Ridiculus cunctos concuteret pueros. / Fistula si dulcis mihi trivisset mea labra, / Risibus et ludis oscula conciperem. / Veridicax minor est vobis quam ligula mendax, / Diligitis iocos en mage quam metricos. / Ludere carminibus melius namque esse decrevi, / Que faciunt animum crescere et ingenium / […] /Diligo vos animo, corde simul doceo / […] / Eia, confratres, certemus carmine metri; / Hoc vincens aliquis sit melior reliquis.’

- Berthold of Reichenau, Vita Herimanni, chap. 3, 10.

- Berthold of Reichenau, Vita Herimanni, chap. 2, 6-8: ‘Quamvis ore lingua labiisque dissolutis, fractos et vix intelligibles verborum sonos quomodocumque tractim formaverit, tamen auditori-bus suis eloquens et sedulus dogmatistes tota alacritate festivus et in disputando promptissimus et ad inquisita illorum respondendo morigerus minime defuit… Homo revera sine querela, nihil humani a se alienum putavit […] misericordiae cultor hilarissimus […] Mirae benevolentiae af fabilitatis, iocunditatis et humanitatis omnifariae conatu sese omnibus morigerum et aptum exhibens, utpote omnibus omnia factus ab omnibus amabatur’.

- Manitius, Geschichte, 2. 769: ‘dass uns der Dichter einen tiefen Blick in seine der Welt zwar abgestorbene, doch mit der Welt keineswegs unbekannte Seele tun läst [sic].’

Chapter 8 (163-184 from Horizontal Learning in the High Middle Ages: Peer-to-Peer Knowledge Transfer in Religious Communities, edited by Micol Long, Tjamke Snijders, and Steven Vanderputten (Amsterdam University Press, 07.19.2019), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported license.