The medieval information commons as a deep stratum of our present culture.

By Dr. Kathleen E. Kennedy

Global Professor

British Academy

University of Bristol

Introduction

The “Renew, Reuse, Recycle” motto of late twentieth- and twenty-first-century America had an early twentieth-century echo from the Great Depression and World War II: “use it up, wear it out, make it do, or do without.” Both phrases express the importance of making things as useful as possible for as long as possible, and the earlier expression recognizes that a failure of sustainability leaves us bereft. For hackers, sustainability is a passion. In an era of disposable electronics, hackers are keen to extend the functioning lives of machines by repairing them or reprogramming them. Hackers may expend this effort out of selfishness, out of simple joy in hacking, but may also act for the common good. To accomplish this, however, hackers must truly own the “boxes” they modify; this is a current point of contention between hackers and electronics manufacturers. Even the first iPad had no way for an owner to access the battery (without a sledgehammer). Tablet and iPad screens tend to be fused to the motherboard, prohibiting any significant repair and requiring replacement of most of the unit, rather than replacing individual parts. Likewise most software cannot be customized, developed, or even fixed except by specialists licensed by the software company. Such single-purposefulness and limitation of code, of text, frustrates modern hackers, and would not even have been possible in medieval manuscript culture.

This essay establishes the information commons as a deep stratum of our present culture. As such, the medieval information commons affects our modern world both indirectly through intervening cultural layers, and directly, in those narrow places where the information commons persists. Texts in medieval England were common to the point of promiscuity. Anyone with the skill to write could copy any text. Further, anyone could modify that text by adding or subtracting, developing, or translating the text into another language. Examples of such hacking in literary texts are legion. The elaborate revision history (some authorial and some not) of the long poem Piers Plowman is an extreme example.1 However, we might think too how the monk and poet John Lydgate “completed” Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales with additional material. Another cleric, Richard Maidstone, translated and paraphrased the Penitential Psalms, and this paraphrase was selected by a patron or copyist to replace the Latin Penitential Psalms in an otherwise Latin prayerbook.2 There is no reason to suspect that the people making and reading these works of literature were hackers self-consciously: their products championed commonness, openness, and freedom only because their textual culture promoted these ideals generally. The iPad’s inflexibility was simply not conceivable in such a culture.

Today literature is heavily copyrighted, but it was manifestly part of the information commons in the Middle Ages and is therefore unsuitable to use as a control group. For my purposes, I had to investigate a form of text that could conceivably have been controlled in order to establish that what we today call the information commons existed in late medieval England and was the normal state of affairs. Instead of literary examples, therefore, I chose statute law as my exam-ple because it was as controlled as the Middle Ages could manage. If the powerful in medieval England could control a text, the texts of the law would seem to be where they would concentrate that ability. If examination shows that law texts do not remain controlled, if they acquire layers of accretion and shift and bend according to copyists’ desires, then either institutional control was ineffective, or there was no real effort at control at all, and texts were universally part of an information commons. (Remember that just as a commons is guided by custom, so an information commons does not suggest a free-for-all.) As we do today, the medieval English had a legal system based both on written law, statutes agreed upon in parliament, and on precedent law, determined in the courts.

Unlike literature, medieval English law was as close to monolithic and proprietary as could exist at the time. As law, the authoritative text of the statutes was not supposed to vary. In order to preserve that fixity, statute law existed in the learned languages of Latin and a special dialect of French, called “law French.” In England, the text of laws had to be carefully and correctly stated whenever it was used: precise wording mattered. To establish that precise wording, the only official copy of the statutes was the Statute Roll kept at the Exchequer, and not a single copy elsewhere had formal legal validity.3 When copies were made, we even have evidence of them being checked for accuracy against the Statute Roll.4

Despite all this cultural regulation, however, evidence abounds that the statutes were part of an information commons. In fact, the ad hoc modification of statutes supports in a striking and surprising fashion Hardt and Negri’s caution that the common is not public, as it is distinct from the regulations directing the use of a common. Despite their unofficial status (once duplicated), statutes were copied in legion: nearly 500 copies of statute collections remain from medieval England.5 Only a tiny minority of these copies was formally checked against the Statute Roll for accuracy. Statutes were also modified and developed in various ways. They were translated into English, the common tongue, but not a language used much in formal legal practice until later in the fifteenth century. Remarkably, statutes in English were even edited: local law and custom was sometimes threaded through national law in “quilted” legal anthologies.

Law translators are analogous to modern computer programmers. The law translators we study in this essay had access to the languages necessary for translation, just as modern computer hackers have access to the “learned” computer languages. Also, law translators had access to exemplars of the texts to be translated just as computer hackers rarely build code from scratch, but begin with an exemplar, which they modify. Both law translators and computer hackers move easily inside the information commons. Both work to make texts useful.

Perhaps the most-used statute in medieval England was the Assize of Bread, and derivatives of this statute form the concentration of this essay. Few people in medieval England baked their own bread: bread ovens were costly to heat, and so in country, town, and city, people brought their loaves to a communal oven to be baked, or purchased bread directly from professional bakers running those ovens.6 Bread was such a staple foodstuff that its cost was regulated from a very early date at the national and local levels. Dated traditionally to 1256, the Assize of Bread probably fixed in writing customary practices that were much older. The Assize was used to regulate the prices and profits involved with selling bread, and was “one of the most widely enforced statutes in medieval England.”7 Officials assayed bakers’ loaves regularly and the Assize of Bread was more thoroughly developed than the related Assize of Ale, and apparently more consistently policed, an impression that the manuscript record bears out.8 The goal of the Assize of Bread was that a specified loaf would be sold at a constant price, but the weight of that loaf would vary based on the cost of grain.9 Together with tables of weights and prices, the Assize outlined acceptable profits due to the bakers. This range of information challenged medieval copyists and translators, and this essay explores the various solutions they developed to render this body of information useful to their audiences.

The rest of the essay will proceed in three sections. First, I will introduce the shift in language used in law in late medieval England generally. Lessig claims language to be a commons, but surely this is less true of learned languages than the common tongue. Translation is a fundamental kind of textual transformation and produces a derivative text, and such derivatives are normal in an information commons. Additionally, we might think of such derivatives as an additional layer of accretion, sedimented atop the original text. On a wiki such as Wikipedia, one can view all the changes made to a page, and with those revisions in mind the page at any moment in time becomes many-layered. Translation counts as a significant type of revision. Then, I will consider a second type of accretion, textual derivatives. These examples are translations, but they add various kinds of material to the statute text. Finally, I will consider a third kind of accretion, textual derivatives, which alter the form of the statutes themselves. Texts could be laid out in various formats on the page, and in a range of types of volume. For medieval or modern hackers, the proof of success is functionality, utility.10 The range and skill displayed in each of these layers added to the Assize of Bread suggests that for all its counter-intuitiveness, statute law was part of the information commons, and useful textual products were sustainable and could endure in the marketplace for a very long time indeed.

Use It Up: French and Latin as Legal Languages

While a state with laws preserved in learned languages seems impossibly Byzantine today, the complexities of “law English” that have come to replace the specialized Latin and French dialects might appear on closer examination to give cold comfort, as anyone who has labored to read through any Terms of Service knows. Of course, maintaining the law in languages other than the common tongue can be considered a form of control over the law. However, for much of medieval English history, this control was not particularly institutionally directed and derived organically from the languages used in education, Latin and French, rather than artificially, from legislation. Nevertheless, the variety of languages of medieval English law bears on our thinking about law translation as an example of the information commons at work.

Long after the Norman Conquest rendered French and Latin the languages of government and law in England, English began to be discussed formally as a potential legal language beginning in 1362, with the Statute of Pleading, the first law concerning legal language in English history.11 While everyone in late medieval England had a good chance of being exposed to English, French, and Latin regularly, levels of comprehension and fluency could vary enormously.12 A law concerning legal language falls into Hardt and Negri’s “public” category: it seeks to regulate the use of the common, of the language itself. In the Statute of Pleading, however, the regulation was to increase use of the common (in whatever limited a fashion), rather than restrict it. This is the one example I have found of hacker rhetoric that did not occur at a time when the medieval information commons was threatened with restrictive regulation. Given that information commons function inside custom, however, any legislative (public) regulation might be productive of a statement of hacker values, whether that legislation was restrictive or not.

Though the Statute of Pleading was no great leap forward for English, nevertheless it expresses rhetoric of linguistic access that we will see used by hackers throughout this book, and it sounds a number of complaints with the legal system which we shall see reinvoked in the early sixteenth century:

great misfortunes have befallen many of the realm because the laws, customs, and statutes of the said realm are not commonly known in the same realm, since they are pleaded, counted, and judged in the French language, which is very much unknown in the said realm, so that the people who plead or are impleaded . . . have no understanding or knowledge of what is said for them or against them by their [lawyers].13

A corollary was that if courtroom dialogue was in English, “the said laws and customs would be learned and known and better understood in the language used in the said realm, so that every man of the said realm might better organize his affairs without offending the law.”14

While only commonness is invoked in the Statute of Pleading explicitly, openness is also implied. The statute law was common to all and was supposed to be common knowledge: the implication is that it should be open, accessible, to all. If the law was not open, this put the common people at risk, and ran afoul of the Magna Carta’s provisions against unjust punishment and imprisonment, and for regular legal procedures. Law that is not practiced “commonly” leads to “great misfortunes.”

In 1362, neither parliament nor the king was arguing for a legal information commons, as the document itself makes clear. The statute is recorded in law French, and ends with the king demanding that, while courtroom procedure was to take place in “in the Tongue of the Country,” law was to be recorded in Latin.15 So much for an open, common law—the statute shows no interest in making English law more transparent for the common people at large, but simply for a slightly larger group than previously. Notably absent from this statute is any explicit rhetoric about the common good, an additional line of argument employed by legal translators in the sixteenth century.

Yet, following the custom of an information commons, the common tongue made inroads into the law, like one layer of sediment gradually covering another. The greatest shift toward English use in the law occurred in the fifteenth century, and most of the “hacked” statutes discussed in this essay date to that century. Evidence exists that beginning in the 1362 parliament, English was used increasingly by the House of Commons, as well as in the assembled Parliament, containing the Commons and the House of Lords.16 Personal communications of the King began to appear in English under Henry V (1413-1422).17 The office of the Privy Seal switched to using English after the 1420s.18 The parliament rolls began to be kept regularly in English after 1450.19 The court of Chancery recorded appeals in English consistently beginning in the reign of Henry VI too (1422-1461, 1470-1471).20 The text of royal proclamations was composed in English beginning in Edward IV’s reign (1461-1470, 1471-1483).21 Statutes began to be printed in English under Henry VII (1485-1509). However, the transition to English law was not complete for centuries (sedimentation can take a long time). The Chancery did not issue anything under the great seal in English in the fifteenth century at all, and the great financial arm of government, the Exchequer continued to use Latin in its instruments until the nineteenth century.22 While Latin and French were not entirely “used up” in this period, the fifteenth century marked a growing acceptance of written English, an acceptance echoed in the manuscript record of English translations of the statutes.

Make It Do: The Texts of the Assize of Bread and the Statute of Winchester

Unless they wished to “do without,” people “made do” by transforming the statutes in significant ways, and adding layers of textual accretion. In all of the cases we will examine below the statutes have been altered from the official version to greater or lesser degrees, demonstrating that users felt free to modify these legal texts to suit their own local conditions. These transformations are striking when we consider the fixity usually ascribed to the text of laws.

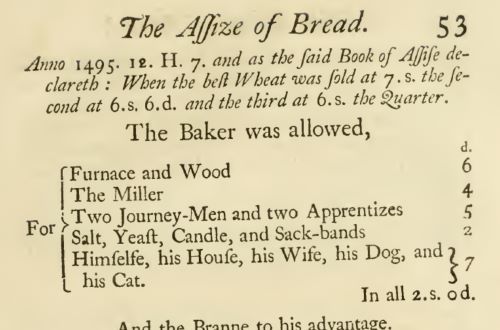

In the modern record of the Old Statutes, the Assize of Bread uses the following terms:

When a quarter of wheat is sold for 12 pence then wastel bread of a farthing shall weigh 6 pounds and 16 shillings. But bread cocket of the same grain and fineness of flour shall weigh more than wastel by 2 shillings. And cocket bread made of lower price grain shall weigh more than wastel by 5 shillings. Bread made into simnel shall weigh 2 shillings less than wastel. Bread made of whole wheat shall weigh a cocket and a half. Bread of treet (bran) shall weigh 2 wastels. And bread of wheat shall weigh two great cockets. When a quarter of wheat is sold for 18 pence then wastel bread of a farthing white and well baked shall weigh 4 pounds, 10 shillings, 8 pence. [continued list of prices] And it is to be known, that in every quarter of wheat, as it is proved by the King’s Bakers, a baker may gain 4 pence, and the bran, and two loaves in profit. For the three servants, 1 pence, a halfpenny for two lads, the same for salt, for kneading, for candles, 2 pence for wood and a halfpenny for the sifting.23

Today this reads slowly, if we can make our way through it at all. Part of the confusion is the mixture of unfamiliar volumetric measures with weights and prices. Overall, as the price of a measure of grain, called a quarter of wheat, rose, the size of a loaf made from flour derived from that quarter of wheat was supposed to decrease so that the price of it remained the same. Bran bread was heavy and dismissed as the poorest quality. The finest, lightest flour produced the purest white bread. In this way, in theory, people could always afford to purchase bread, though a lesser quality or quantity when grain prices were high. At the same time, the profits due to the baker were spelled out carefully, not only how much profit he was to take, but also the business expenses that profit covered.

Given how necessary it was on a regular basis, the Assize of Bread is one of the most common laws to be found in English translation.24 Since its goal was protection for both consumer and producer, it is no surprise to find it revised to suit local conditions: as James Davis points out, “overall the implementation of[the Assize of Bread] in the localities was a vibrant example of how central initiatives could be successfully adapted and interpreted through local courts and officials.”25 In laws like this one, vocabulary plays an important role: specific types of bread made of specific types of flour and baked in certain ways must be identifiable to the statute’s audiences.26 While there was certainly overarching similarity in bread names across medieval England, any official had to figure for local practices and conditions whether using the original Latin or an English translation.27 We should not be surprised, therefore, to find some differences in vocabulary in independent translations. For example, one copy lists prices for various weights of wastel, simnel, white, whole wheat, and multigrain bread, rather than the wastel, cocket, simnel, whole wheat, treat, and multigrain types listed in the Assize.28

The information commons allowed not only for translating the Assize, but also for conforming it to local conditions, and this combination appears to have resulted in an entirely fictional “statute,” the Statute of Winchester. The Statute of Winchester has no resemblance to the list of laws concerning local and national security that are the primary preoccupations of the actual Statute of Winchester.29 Basically an abridgment of bread laws, the Statute of Winchester appears in several manuscripts and was printed through 1580: the laws it drew from were all part of an information commons that the initial developers mined in crafting this useful variant. In modern hacker parlance, the bread laws were common: translating them into English made them open, and they circulated freely thereafter.

The ‘Statute of Winchester’ runs thusly:

This is the assize of all kinds of bread. Of whatever type of grain it is it shall be weighed after the farthing wastel loaf. For the simnel loaf weighs less than the wastel loaf by two shilling weight because of its boiling, and the farthing white loaf shall weigh more than the wastel loaf by two shilling weight because of its braiding, and the halfpenny wheat loaf shall weigh the same as three farthing white loaves, and the multigrain loaf shall weigh two halfpenny white loaves. The baker shall be allowed in every quarter for use of the furnace three pence, for wood three pence, for the journeymen three pence, a halfpenny for two pag-es, one penny for salt, a halfpenny for yeast [or starter], a halfpenny for candles, a halfpenny for the tie-dog, and all the bran to the baker’s profit. And this is the Statute of Winchester.30

The Statute of Winchester contains an expansion of the basic protections for consumer and baker allowed in the Assize and other national bread laws, and is therefore a derivative of the Assize. In stratigraphic terms, the Statute of Winchester is made of material overlaid onto the Assize of Bread, and the two layers must be read together today, as they must have been in the fifteenth century. The first section outlines relative weights and prices and follows the Assize of Bread generally, but in a more finely grained way. The Statute of Winchester links many of these types of bread and their weights to processes of baking specific types of bread. The farthing wastel loaf was boiled like a bagel, and the farthing white loaf was braided, each creating not only uniquely weighted bread, but also a specific texture and appearance. The second half of the Statute of Winchester loosely translates a chapter of the actual Assize that details allowable profit for the baker. As in the first half, this second half is more finely grained than the official Assize. The Statute of Winchester details profit to be put towards baking, wood, servants, salt, yeast (or starter, as in sourdough), candles, and the “tie-dog” presumably in charge of keeping mice and vermin out of the flour and perhaps shoplifters away from the baked goods.31 Clearly the Statute of Winchester developed layers of accretion, as did the Assize itself. The text of the Statute of Winchester demonstrates vividly that even the statutes were situated in-side the information commons.

Wear It Out: Forms of the Assize of Bread and the Statute of Winchester

As radical as adding specifics to laws might seem to us today, the medieval information commons extended farther yet. The text of the Assize and the Statute of Winchester could be developed into a range of forms on the page. Containing both instructions and lists of numerical ratios, these complex texts put great demands on layout, and copyists developed a variety of creative responses. In this last section of the essay I will explore four different kinds format choices made by copyists of the bread laws that illustrate the flexibility allowed in this information commons. First, we will quickly consider copies emphasizing columns over long lines of text. Second, I will introduce laws copied on rolls rather than in books. Third, we will examine several almanacs that carried their schematic design over for use with the included bread laws. Finally, we will end with the cycle of pictures added to the Statute of Winchester, the only illustrated English law in history. Each of these transformations changes the use of a copy, and constitutes another layer of accretion on the text.

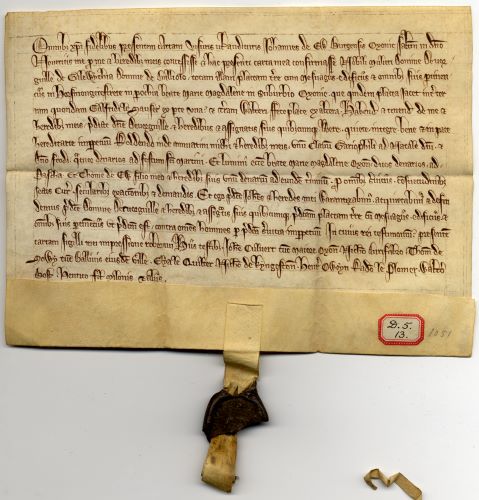

In addition to vocabulary and decoration, copyists of the statutes also had to make decisions about layout. Though often unrecognized, layout influences how a text is used, and even how functional it is. For example, the Latin copy of the Assize of Bread recorded in the modern edition of the Statutes, called the Statutes of the Realm and prepared by the Record Commission, is a complex text. Parts are composed of sentences in paragraph form, but much of it simply lists bread types, weights, and prices, all written out in long lines. In such a format the law is difficult to read. The Record Commission’s translation in the facing column is revealing: in translating the language, they also translated the format, and in the English, the sentences are organized into paragraphs and the lists into short-line list format.32 This practical approach has medieval precedent, as at least some copies of the Assize reformed those lists into two columns of short lines.33

Their form suggests that two such “reformist” manuscripts were designed for use as ephemera: alone among the volumes examined in this book, both show that they were initially designed as rolls, rather than as codices or “books.”34 Unlike scrolls that unspool horizontally, rolls scroll vertically. Rolls are believed to have been once far more common than their extant numbers would suggest, as they were used for their easy portability (and I think inexpensive manufacture) rather than their sturdiness.35 While we can guess that miniature statute collections were crafted for ease of transportation, because they are (or were) rolls, we can be more sure that these two copies were working texts, designed to be used frequently.36 It is little surprise that the Assize of Bread (and the Statute of Winchester) would be found in such a format: these laws formed a part of everyday medieval life.

Like rolls, almanacs were once a far more common kind of medieval ephemera than extant numbers convey. Almanacs tended to be small and portable. At least some were protected originally by small cases, like analog smartphones, to survive the rigors of being worn on the person and continually perused.37 Some were tiny codices, but an English specialty was the folded almanac, a very large sheet of parchment folded into a tiny booklet.38 Not unlike a smartphone their burden of keeping time came to be aggregated with a mass of other short useful materials. Religious calendars marked saints days, but also the dates of Easter and movable feast days, lunar calendars, and astrological information like the zodiac chart. Some calendars included charts or short lists of kings. Almanacs also served predictive functions, and short texts or figures predicted weather, quality of crops, and health of animals. While some almanacs could contain more specialized, medical material, many did not.39 Schematic retellings of biblical texts and short prayers could appear in almanacs, as could charts of weights and measures.

Like smartphones, almanacs were densely visual texts: light on words they were heavy with numbers, charts, pictures, and icons through which users navigated to find and make use of each text. Though the iconic images might seem entirely opaque to us today, they were originally chosen for their simplicity and the ease with which they conveyed their frequently unwritten, or heavily abbreviated texts. Indeed, the Assize of Bread (and sometimes the Statute of Winchester), particularly its more abstract lists of numbers and ratios, fit into an almanac layout better than any other setting.

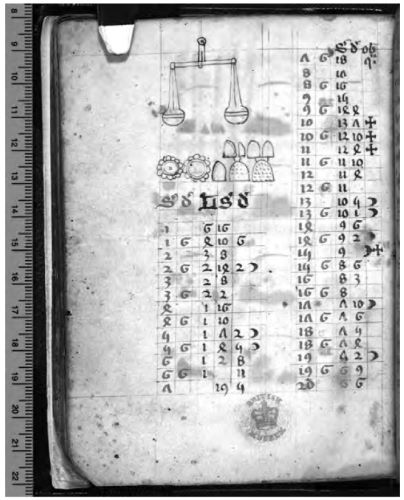

Reminding us of the normality of the information commons in late medieval England, a small group of almanacs remaining today are all based on the same text.40 This alone is an extraordinary coincidence. These almanacs concentrate on astronomical science, and while miniature, nearly every page is full of carefully drawn charts and images.41 One of the texts common to each of the almanacs in the set is the Assize of Bread. Originally the Assize in these three late fourteenth- and early fifteenth-century almanacs included no text at all, reducing the Assize of Bread to an abstract table of numbers sometimes topped by very basic depictions of loaves, and in one case, a set of scales.42

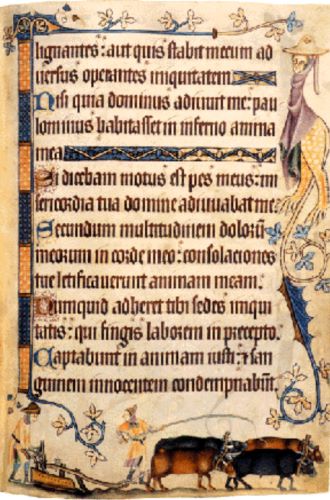

The lack of text associated with the Assize of Bread in almanacs sometimes worked against it and the “worn out” statute was “renewed” with the addition of textual explanation: the Statute of Winchester. The final text originally in one of these almanacs was the Assize of Bread, and at some point a reader determined that the Assize required updating and “made do.” This page is described as a “table . . . of weights and measures”: however, we can be more specific.43 This abstract table is an almost precisely copied set of ratios drawn from the Assize of Bread, one laid out in a tabular form far more severe than either roll discussed earlier (Fig.1). The color of the inks, style of the accompanying drawings, and ruling all suggest that this table was planned as part of this almanac, and it resembles those of the other two related almanacs.44 However, in time this almanac’s very economy of text appears to have worked against it, and the Assize table was “completed” a few decades later.

A later owner of this manuscript apparently found that the table no longer functioned well as it stood. In a hasty hand, the fifteenth-century owner added the Statute of Winchester in English on the leaf following the bread table. Clearly the volume could be seen to need text to complete the chart in order to be useful. In this instance the metaphor of geologic accretion is almost physically realized. Of interest to us is that the text selected to complete the table was this standard, but colloquial, “statute” rather than selections from the textual portions of the Assize of Bread itself. Neither text replaced the other, but both coexisted in the information commons.

The formal variety exhibited by the translations of the Assize of Bread and Statute of Winchester is wide, and indicates just how broad the information commons was. Examples of relatively light development exist, showing simple translation only. Other examples display more radical modification, including linguistic and textual transformation, and, in the almanacs in particular, significant alteration in form. The developers responsible for this range of changes show no hesitation, but rather a confident creativity and exuberance in the face of textual and formal challenges. Perhaps the most striking change of all was the addition of pictures.

Picturing the Law

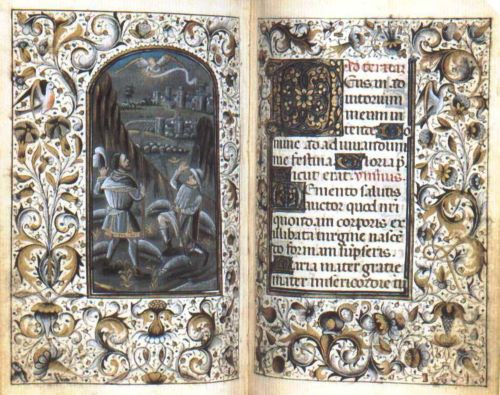

At the same time as the Assize and the Statute of Winchester appear in almanacs, the bread laws demonstrate another formal experiment: illustrations. European law was thoroughly illustrated, and standard visual programs had developed long before the fifteenth century.45 In contrast, law in England was stultifyingly plain. Though some legal manuscripts showed beautifully illuminated borders and initials, the only “pictures” they included were invariably kings seated in judgment. Therefore, the illustrations added to the Assize of Bread and the Statute of Winchester were entirely unique.

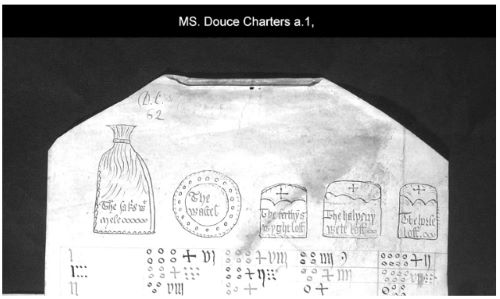

Unlike any other English law, in translation the Assize of Bread and its customary variant the Statute of Winchester appear to have come to carry a simple visual program that appears in multiple manuscripts, and successfully moved into print. One of the roll copies of the Statute of Winchester illustrates traditional iconography for this “Statute”: depictions of a sack of grain and various loaves of bread (Fig. 2). Similar, though far simpler loaves are depicted in the almanacs that we discussed above.46 Beginning with a pamphlet printed in the late 1520s, these complex loaves continue to be associated with the Assize of Bread and the Statute of Winchester until the 1580s. Of note is the standardization of the iconography. In all of the manuscripts and the printed pamphlet, at least one of the smaller loaves is always circular and ringed about with semi-circles or dots, and this pattern seems to relate to the traditional design of this type of bread. In one of the almanacs, catalogers have identified these shapes as weights. If that is true for the abstract almanac images, then the shapes of the weights used to assay the bread were based on the shapes of the types of bread. The roll’s images and the printed pamphlet are detailed enough to be clear that each depicts the loaves themselves, and not simply the weights used for weighing bread. Whether adding functionality for the less literate or simply adding decoration to an otherwise stark legal text, these pictures add to the ways in which these statutes were reformatted when they were translated. In recycling the Statute of Winchester the hackers also renewed it.

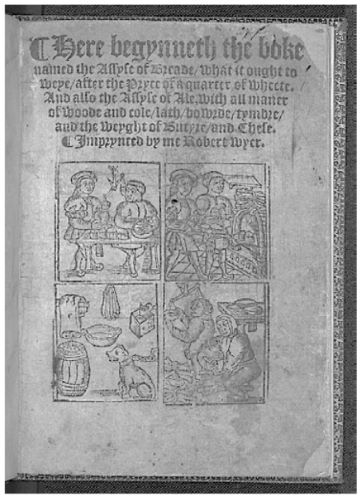

If illustrations might be seen to “open” a text to a wider readership, one final kind of illustration opened the volume in a physical way. Beginning with a pamphlet printed in the 1520s, for most of the sixteenth century the Assize of Bread and the Statute of Winchester bore an illustrated title page, a “cover,” if you will.47 This title page shows a series of four woodcuts depicting baking and assaying bread (and the dog), and these continued to be used in subsequent editions (Fig.3). Together with the cover images, the illustrations of the loaves in this pamphlet are unheard of in a printed English law book. The illustrations, coupled with the accessible translations appear to have been a successful marketing strategy and this remarkable pamphlet remained in print until 1580.48 Through most of the sixteenth century, this pamphlet of bread laws would have been very common indeed.

Each of these derivatives demonstrates the medieval information commons in action in several respects. Both official and hacked traditional texts circulated and were copied freely, and they were modified to update them or to fit them to local needs. Texts could be added to or subtracted from almanacs, depending on an individual user’s needs and interests. Over time, the highly abstract form of the Assize of Bread used in almanacs appears to have become confusing, perhaps as the popularity of the Statute of Winchester grew. In short, the Assize of Bread and the Statute of Winchester both manifest the information commons characteristic of manuscript culture.

If the statute law was more controlled than any other kind of text, then the variety of modifications made to it prove that the information commons was simply the status quo for medieval England. This commons forms a bedrock layer beneath textual cultures built on that of medieval England, including our own. Clearly the modern topography of broadly construed copyright and shrinking fair use in no way resembles its deepest substratum. Yet the information commons persists here and there, and we can see these instance as this medieval bedrock emerging into the modern textual landscape. Not identical to medieval information commons, time and exposure have changed this stratum when we see it today, as with any exposed artifact. Project Gutenberg and Wikipedia are notably different than medieval statute manuscripts, and smartphones are not medieval almanacs.

There were no institutional attempts to control this medieval practice of translating and reforming statutes, just as there were no attempts to control the copying and transforming of literary texts. However, the medieval information commons was not to last. It appears that hackers develop an identity and express their common values at such moments of institutional coercion.

Endnotes

- See the extraordinary book by Lawrence Warner, The Lost History of Piers Plowman: The Earliest Transmission of Langland’s Work (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011).

- New York, Morgan Library, MS M. 99.

- Don C. Skemer emphasizes the unofficial nature of any copy of the statutes in “From Archives to the Book Trade: Private Statute Rolls in England, 1285-1307,” Journal of the Society of Archivists 16 (1995): 194 [193–206]. See also H.G. Richardson and George Sayles, “The Early Statutes,” Law Quarterly Review 50 (1934): 544, 548 [201–223, 540–571].

- Skemer, “Book Trade,” 199.

- For various counts of statute collections, see Skemer “Book Trade,” 201n16; Don C. Skemer, “Sir William Breton’s Book: Production of Statuta Angliae in the Late Thirteenth Century,” English Manuscript Studies 1100-1700, eds. Peter Beal and Jeremy Griffiths (London: British Library, 1997), 24 [24–51]; and Don C. Skemer, “Reading the Law: Statute Books and the Private Transmission of Knowledge in Late Medieval England,” in Learning the Law: Teaching and the Transmission of Law in England, 1150-1900, eds. Jonathan A. Bush and Alain Wijffels (London: British Library, 1999), 115–131 (and note the correction to these numbers, at 115).

- This paragraph is based on discussion in the following: James Davis, “Baking for the Common Good: a Reassessment of the Assize of Bread in Medieval England,” Economic History Review 57 (2004): 465–502, and Claire Fennell, “The Assize of Bread (1256),” in Beowulf and Beyond, eds. Hans Sauer and Renate Bauer (Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2007), 183–196. For bread laws in London specifically, see Gwen Seabourne, “Assize Matters: Regulation of the Price of Bread in Medieval London,” The Journal of Legal History 27 (2006): 29–52. Though primarily concerned with the second half of the twin assize, see also Judith Bennett, Ale, Beer, and Brewsters in England: Women’s Work in a Changing World, 1300-1600 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996).

- Davis, “Baking for the Common Good,” 466. For dating, see Fennell, “Assize,” 184.

- Davis, “Baking for the Common Good,” 466n109.

- Davis, “Baking for the Common Good,” 466.

- This generalization began in the hacker community, and is implicit in Raymond’s stipulation that the quality of a released (non-beta) program is determined by how well it works. See Eric S. Raymond, The Cathedral and the Bazaar: Musings on Linux and Open Source by an Accidental Revolutionary (New York: O’Reilly, 1999), 115.

- The Statute of Pleading has been traditionally, and mistakenly, discussed as a linguistic turning point. See Mark Ormrod’s corrective in “The Use of English: Language, Law, and Political Culture in Fourteenth-Century England,” Speculum 78 (2003): 752 [750–787]. For well-known uses of this trope, see V.J. Scattergood, Politics and Poetry in the Fifteenth Century (New York: Barnes and Noble, 1972), 13, and Albert C. Baugh and Thomas Cable, A History of the English Language, 5th edn. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2002), 149–150. For a longer bibliography, see Ormrod, “The Use of English,” 750n2.

- The foundation for discussions of kinds of literacy and languages of literacy in medieval England is M.T. Clanchy’s From Memory to Written Record: England 1066-1307, 2nd edn. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993). In addition, important interventions have been made in exploring auralities as levels of literacy as well, most notably by Joyce Coleman in Public Reading and the Reading Public in Late Medieval England and France (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1996). For the most recent interventions in the area of French fluency in England, see the essays in Jocelyn Wogan-Browne, ed., with Carolyn Collette, Maryanne Kowaleski, Linne Mooney, Ad Putter and David Trotter, Language and Culture in England: The French of England, c. 1100-1500 (York: York Medieval Press, 2009).

- I use Ormrod’s translation here. Compare Statutes of the Realm, 11 vols. (London, 1810-1825), I:375 (hereafter SoR) to Ormrod, “The Use of English,” 756.

- Likewise, for this section, I have quoted Ormrod’s superior translation. Compare Ormrod, “The Use of English,” 756 to SoR, I:375.

- SoR, I:376. For discussion of languages of written and spoken law before 1362, see George Woodbine, “The Languages of English Law,” Speculum 18 (1943): 395–436, and Paul Brand’s more recent corrections in “The Languages of the Law in Later Medieval England,” in Multilingualism in Later Medieval Britain, ed. D.A. Trotter (Cambridge, UK: D.S. Brewer, 2000), 63–76.

- Ormrod, “The Use of English,” 777–780. For Parliament’s move to use English, see also John Fisher, “Chancery and the Emergence of Standard Written English in the Fifteenth Century,” Speculum 52 (1977): 880n37 [870–899].

- Ormrod, “The Use of English,” 785.

- Ormrod, “The Use of English,” 785. Elna-Jean Young Bentley, The Formulary of Thomas Hoccleve, Ph.D. diss., Emory University, 1965, shows that Privy Seal use in the 1420s remained in the learned languages.

- Fisher, “Chancery,” 880. Fisher’s main concentration, Chancery, records its judicial decisions systematically in English from the beginning of Henry VI’s reign (Fisher, “Chancery,” 888).

- Fisher, “Chancery,” 888.

- Ormrod, “The Use of English,” 786.

- Ormrod, “The Use of English,” 785. See also Fisher, “Chancery,” 877.

- The language of this Assize has been modernized. For the early nineteenth-century English version, and the Latin on which it was based, see SoR, I:199–200.

- Aside from one complete translated collection which includes the Assize, Oxford Bodleian, MS Rawlinson B. 520, I have found eleven manuscripts contain the translated Assize of Bread and Ale in whole or in part: Oxford, Bodleian Library, MSS Douce 16, Douce Charters 62 (also known as Douce Charters a. 1. f. 9), Tanner 407, Rawlinson D. 939; Oxford, Balliol College, MS 354; London, British Library, MSS Additional 36999, Royal 17 A. XVI, Egerton 1995, Harley 2332, Stowe 880, and Lansdowne 796.

- Davis also makes this point, “Baking for the Common Good,” at 467, 492.

- Fennell notes that the vocabulary used and the different ways of describing bread vary in many manuscripts (“Assize,” 189–190).

- Davis notes that the enforcement of the Assize was very much up to local officials and local interpretation (“Baking for the Common Good,” 488, 492). Bennett’s study is founded on the reality that local enforcement of the Assize of Ale was based in local practice, and states that when the Assize was kept, what was at question was broadly the national assize, and more particularly local practice (Bennett, Ale, Beer, and Brewsters, 99).

- Further, I think it likely that Additional 36999’s missing header or footer originally included more text, either from the Assize or the Statute of Winchester, and that its missing header included the images of loaves so frequently accompanying the Statute of Winchester.

- The actual Statute of Winchester can be found on SoR, I:96. Note that the English translation is based on a mid-fifteenth-century English translation, now Kew, National Archives, MS C/49/2/10.

- I have modernized the syntax, spelling, and punctuation: “Thys ys the syse of al maner of brede what greyne of corne so evyr yt be yt schal be weyd aftyr the ferthyng wastel for the sem-nel weygeth lasse than the wastel be ii s by cause of the sethynge and the ferthyng wyght lofe schal wey more than the wastel be ii s be cause of the braydyng and the halpeny wete lofe schal wey iii ferthyng wythe loffis and the lofe of al maner corne schal wey ii [halfpenny] wyth lofys and the baker schal be alowyd in every quart for fornage iii [pennies] ffor wode iii [pennies] for the jorneymen iii [pennies]. [halfpenny] ffor ii pagys i [penny] [halfpenny] ffor salt [halfpenny] for barme [halfpenny] for can-del [halfpenny] ffor the teydogge [halfpenny] an al the brenne to [his] awantage. And thys ys the statuyt of wenchester.” This is a diplomatic edition based on Douce Charters 62, with consideration of copies in Harley 2332, fol. 22r and the printed pamphlet, STC 864, fol. A2v. Abbreviations have been silently expanded and small contradictions smoothed for sense. In addition to these manuscripts and printed books, there may be at least one other copy in manuscript, though it is not included here: William Forster Lloyd printed a late fifteenth-century copy from what appears to be a legal collection in manuscript at the Bodleian Library, although he gave no shelfmark and I have not been able to identify the copy. See William Forster Lloyd, Prices of Corn in Oxford in the Beginning of the Fourteenth Century (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1830), 87–88. Weights and measures are usually retained in Latin abbreviations; editorial practice here is to expand them into modern English and place them in brackets. This word supplied from STC 864 and Harley 2332; Douce Charters 62 has “ferthyng” here, apparently an eyeskip. STC 864 uses “eyst.” Douce Charters 62 uses “varme” but appears to mean “barme,” the skim of live culture on top of brewing beer (see Middle English Dictionary [MED], “barme”), which suggests a bread starter to me. Harley 2332 uses “barme.”

- See MED, “tei(e”, [n.1]).

- This base text is London, British Library, MS Cotton Claudius D. II; see SoR, I:199–200.

- These are Additional 36999 and Douce Charters 62. The preparer of Additional 36999 also worked out the calculations more fully than in the copy the Record Commission printed. The text of the Assize of Bread in Additional 36999 is quite close to that found in the Statutes of the Realm, but follows the collated text from Liber Horn more closely than the Record Commission’s selected base text in its names for types of bread, possibly suggesting a London provenance. Additional 36999 is incomplete at both ends, and so we cannot know how perfect the wordier parts were: the paragraphs that precede and complete the statute are missing, if they were ever there at all.

- Additional 36999 is a roll, and Douce Charters 62 shows stitching evidence, suggesting that it used to be part of a roll. For an image of Douce Charters 62, go to http://bodley30.bodley.ox.ac.uk:8180/luna/servlet and search “Douce Charters 62.”

- Skemer, “Private Statute Rolls,” 198. It should be noted that Ske-mer is referring to an Exchequer-style roll, however, and not the continuous (and larger) Chancery-style roll. Additional 36999 is in the Chancery style.

- Miniature and very small statute collections turn up regularly in libraries. Examples I have viewed from the time period covered by this book are: Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Douce 16, which also happens to have an English translation of the Assize of Bread added to the flyleaves, and MS Douce 27; Cambridge, University Library, MS Additional 2827, MS Dd 15. 18, MS Ii 6. 10, and MS Ii 6. 25.

- Despite how ordinary such books must once have been, almanacs are little studied. The following introduction is based on P.R. Robinson, “‘Lewdecalendars’ from Lynn,” in Tributes to Kathleen L. Scott: English Medieval Manuscripts: Readers, Makers, and Illuminators, ed. Marlene Villaloboss Hennessy (Turnhout: Harvey Miller, 2009), 221–230, and John B. Friedman, “Harry the Hayward and Talbot his Dog: An Illustrated Girdlebook from Worcestershire,” in Art into Life: Collected Papers from the Kresge Art Museum Medieval Symposia, eds. Carol Garrett Fischer and Kathleen L. Scott (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 1995), 115–153. For examples of these cases, see Hilary M. Carey, “What is the Folded Almanac? The Form and Function of a Key Manuscript Source for Astro-medical Practice in Later Medieval England,” Society History of Medicine 16 (2003): 490 [482–509].

- Carey argues that the folded almanacs were an English innovation (“What is the Folded Almanac?” 502).

- For information on medical almanacs, and the difficulty in ascertaining which count as such and which do not, see Carey, “What is the Folded Almanac?” and Hilary M. Carey, “Astrological Medicine and the Medieval English Folded Almanac,” Social History of Medicine 17 (2004): 345–363.

- Friedman claims that the other almanacs discussed here were modeled directly on Rawlinson D. 939 (“Harry the Hayward,” 132).

- For non-legal materials in almanacs, see Friedman and Robinson generally. For images of several of the almanacs discussed here, see http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Default.aspx, a digitization of London, British Library, MS Harley 2332.

- Rawlinson D. 939, Section 4, recto; Royal 17 A XVI, fol. 23; and Harley 2332, fol. 21v. The Royal manuscript does not include images, just the chart of numbers. While two of the three almanacs are small codices, Rawlinson D. 939 is an enormous set of connected sheets that was designed to fold down to pocketsize. London, British Library, MS Sloane 1313 is another medical anthology that includes a single statute concerning bread, but this one is the Statute Concerning Bakers, and the entire anthology is in Latin.

- Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts, http://collectbritain.co.uk-/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/record.asp?MSID=8837&CollID=8&NStart=2332 (accessed May 18, 2014).

- Nevertheless, Rawlinson D. 939 uses an arrangement of circles and minims as units of number rather than arabic numerals.

- For recent discussion of Continental and canon law illustration, see Susan L’Engle and Robert Gibbs, Illuminating the Law: Legal Manuscripts in Cambridge Collections (Turnhout: Harvey Miller, 2001) and accompanying website: http://www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/gallery/law/. And for a probing exploration into the relationship between Continental law and images, see Marta Madero, Tabula Picta: Painting and Writing in Medieval Law, trans. Monique Dascha Inciarte and Roland David Valayre(Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009).

- Harley 2332; Royal 17. A. XVI; Rawlinson D. 939.

- My policy below will be to give complete citations for texts I discuss in the chapter, and STC numbers alone for simple references. STC 864: “Here begynne the the boke named the assyse of bread what it ought to waye after the pryce of a quarter of wheete,” Richard Bankes [London, not after 1532]. For more discussion of this pamphlet, see Kathleen E. Kennedy, “A London Legal Miscellany, Popular Law, and Medieval Print Culture,” in Truth and Tales: Cultural Mobility and Medieval Media, eds. Nicholas Watson and Fiona Somerset (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2015).48 STC 866 (Robert Wyer, 1544?), STC 867 (Wyer, 1546?), STC 868.2 (Wyer, 1553?), STC 868.4 (Wyer, 1555?), STC 868.6 (Colwell/Wyer, ca.1560), STC 868.8 (Colwell, 1570), STC 869.5 (Jackson, 1580), and STC 869 (Jackson, 1580).

Chapter 2 (29-54) from Medieval Hackers by Kathleen E. Kennedy (Punctum Books, 01.16.2015), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported license.