Sport is a very similar type of action to religious ritual.

By Dr. Evangelos Kyriakidis

Senior Lecturer in Aegean Prehistory

University of Kent

Ritual is a category of action that has had many definitions and almost every researcher terms it in a different way. Although some have praised the lack of a definition (e.g. Bell 2008, 277-288), this is a major handicap for the study of ritual as it is difficult to compare ideas without a firm grasp of what two scholars mean when they make reference to the term. The slippery definition is a result of both the intangibility of ritual as well as the large number of people who have an opinion on the matter: everyone knows a lot about rituals. Seeking common denominators, or the crowd-sourcing of definitions (Brabham 2008, 75-90) cannot lead to a satisfactory solution until we have a number of scholars who actually state what they mean by the term and have written on the topic. For the purposes of this paper I will use my own definition of the term which I have been using for the past 5 years. According to this definition (Kyriakidis 2008, 289-294):

Ritual is an etic (Lett 1990, 127-129) category that refers to set activities with a special (not-normal) intention-in-action, and which are specific to a group of people.

The fact that ritual is a set category is, I believe, a factor that can distinguish ritual from sport. Like ritual, sport and games are set in that they are rule-governed and repeated activities with an undetermined ending, i.e. nobody knows who will win (this is why game fixing is a crime). Ritual, on the other hand, is set also in that it has a pre-determined outcome.

The fact that ritual is a set category that has a predetermined course of action may make it seem to be free of risk. There are several reasons why this is not the case:

Firstly, we have already mentioned that ritual is an etic category, i.e. an observer’s category, not primarily an initiate’s/insider’s category. It is mainly for the observer that ritual is a set category. For initiates, and especially lower-level or new initiates, rituals can often give a false sensation of uncertainty as to what happens next. Only those who can see outside the box, often in the higher echelons of initiation, may be aware of ritual invariance.

Secondly, the successful performance of the ritual is not itself predetermined, and all performance-based activities, both sport and ritual are risk prone (Shieffelin 1996, 60). It can not be known in advance whether a liturgy will be completed, or whether a bull will be sacrificed. We are not sure whether the Orthodox Patriarch in Jerusalem will come out of the inner chamber of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, apparently the tomb of Christ, with the ‘Holy Fire’ one day before Easter as he has been doing every year for the last millennium (Peters 1985, 262). Ritual failure refers mainly to this type of uncertainty.

It is important here to explain what we mean by ritual failure. A specific ritual, e.g. a Sunday church liturgy can be seen as a category in its own right. Categories have specific traits that are necessary for an item’s classification as such, which are called definitive criteria: Sunday church liturgies have to occur both on a Sunday and in church; otherwise, if planned under that rubric and do not satisfy these two conditions, they cannot be classified as such and will fail. A human sacrifice, to use an extreme, has two main ingredients, the involvement of a human, and death; if a rabbit is slaughtered instead or if a human is involved but does not die, the ritual fails as such.

There are also traits in a given category that are not crucial for membership in that category: the priest does not have to read all the hymns correctly to the letter in order for the Sunday church service to be classified as such. Failing in one of the non-crucial traits of ritual does not constitute ritual failure, but rather a deviation. We must make clear however, that ritual failure does not refer to ritual dissolution (e.g. see Chao 1999, 505-534 and esp. 534), the death of a ritual, though it may indeed contribute to such dissolution.

Moreover, ritual is often associated with risk, although ritual itself may not be uncertain. We are uncertain whether a sacrifice will be accepted by the gods, even if the performance of the sacrifice itself has been completed successfully. We are not sure whether the performance of a divination ritual will have the desired result. It is impossible to know in advance whether a magic spell will have the intended effect. In this respect risk is not part of the ritual but associated to it, it is an aftermath of ritual. It is this association with risk that is the most common in rituals.

If we bundle various actions into packages, large or small, we will soon discover that there are ritual packages which include mundane actions, and, conversely, mundane packages that include ritual actions. Very often rituals are embedded in packages that are not themselves ritual. For example the package ‘mundane dining’ may include a prayer ritual, the package ‘university study’ may include matriculation, graduation and other rituals. Also, non-rituals are sometimes embedded in ritual packages: liturgy in a church may be interrupted by a passing of the basket activity for contributions by the community; or a funeral may include coffee drinking, chatting, quarrelling with the cemetery authorities for all sorts of reasons, or even sports – as the ones Achilles organised for the funeral of his friend Patroclus in Iliad 23. Risk therefore may exist in a mundane activity that is thus associated with ritual. This type of risk is extrinsic to ritual.

Howe (2000, 69) identifies extrinsic and intrinsic types of risk, the former being “risks which accompany the enactment of a ceremony but are not built into the structure of the rite” and the latter being “integral to the rite itself, part of its very essence.” Although I do not follow Howe’s definitions, since there is no disjunction between the enactment of the rite and its performance, I do agree that there is a valid distinction between intrinsic risk, risk that is built into the rite itself (will the performance of the rite be successful, will the ritual be a ritual or not?), and extrinsic risk, i.e. risk that is associated with the rite but is not part of it (will the gods appreciate the sacrifice or not?).

There is often an effort to manage risk in rituals (e.g. Schieffelin 2007, 1-20), particularly those that are institutionalised (i.e. when there is a group of people/institution responsible for their performance –see Kyriakidis 2005, 74-79). Attention is given primarily to managing the intrinsic risks, but also to a lesser extent the extrinsic ones, so that on the one hand their effects are ‘guaranteed’, and on the other performers do not suffer. Early Chinese oracle bone divination rituals (see Flad 2008, 403-419) for example, showed a development that helped manage that risk. Drill holes in the bones that were used for these rituals ensured controlled cracking that would help the performers produce desirable results, thus both protecting the performers and ensuring that the ‘clients’ were sufficiently enthralled and satisfied by the rites.

It is important here to remind ourselves that ritual is not irrational, unreasonable, illogical or non-contiguous to its performers. To them, ritual is very similar to technology (see Marcus 2006, 221-254; Nikolaidou 2008, 183-208; Kyriakidis 2008, 291), i.e. a set way to do things, be that invoking rain, communicating with the gods, or curing disease. Ritual as a technology is a collection of learning mechanisms through every one of its characteristics, as I have argued elsewhere (Kyriakidis 2005, 69-72). In fact risk, or uncertainty, probably constitutes one of the most important traits for ritual in terms of its function as a learning mechanism, although this is a trait which I have not previously discussed.

Risk or rather uncertainty is recognised as one of the strongest learning facilitating mechanisms. The concept of blocking (Kamin 1969, 242-259) in psychology was crucial for identifying the value of uncertainty in conditioning (learning). Blocking is the process by which the association of a reinforcer with a second stimulus is blocked (or hindered) once there already has been an association between that reinforcer with another stimulus. For example, the association between a bell (stimulus) and food (reinforcer) arriving is hindered if there has already been an association between a light (a second stimulus) and food arriving (reinforcer).

Pearce and Hall 1980, 532-552) have extensively argued that the effects of ‘blocking’ do indeed take place but due to a different mechanism from the one just mentioned. They have argued that the first time the light-stimulus appears there is heightened attention (and therefore faster learning) by the beholder due to the uncertainty of what this stimulus is to be associated with. Once a stimulus has been associated with a reinforcer (food), then attention is reduced and further associations are hindered. According to Pearce and Hall, therefore, uncertainty about what comes next is a mechanism that heightens attention and facilitates learning. Their argument is too complicated to present here fully, but it suffices to say that ‘the more uncertain an animal is about a stimulus, the faster it learns about that stimulus’ (Dayan and Yu 2003, 176-177).

Risk in other words, is a strong learning mechanism. This characteristic could arguably make rituals not risk averse, as one may imagine, but risk prone. It is this ‘learning’ facet of risk that is a desirable effect in most rituals and needs to be maintained. Thus the challenge for managing risk in rituals lies in how to avert the potentially detrimental risk for the performers (especially in the higher echelons of initiation), while on the other hand keeping this beneficial learning aspect of risk and a number of strategies may be formulated to that end (e.g. internalising risk, see Schieffelin 1996, 59-89, or attempting to explain this failure in terms of the ritual itself, see Schieffelin 2007, 1-20 and Michaels 2007, 121-132).

Returning to the distinction between sport and ritual, we have now seen that not only sports, but also rituals can have an uncertain outcome. This would apparently eliminate this difference between ritual and sport. There is a significant difference however. In sport each performer may want a specific outcome, i.e. winning (in some even cases they may be certain of it!) but observers always see a different end; during each ‘performance’ one cannot predict the outcome. In ritual performers often may not know the end, yet observers can see an invariance (albeit fragile in some cases), a stable performance with a predictable end that, if nothing goes wrong, occurs every time.

I would also argue that risk, and especially intrinsic risk, is managed differently between the two types of activity. Managers of sport may stress the uncertain ending of sport which in fact is the essence of the whole activity (beyond the rules): ‘Which team will win? Who will run the fastest? Who will beat whom in the boxing match?’ ‘Come and find out for yourselves’. Managers of ritual, as we saw above, would not stress this unknown end in describing a ritual. People are invited to go to a matriculation ceremony, or a wedding ceremony. Potential failure is not part of the narrative (though it does happen sometimes). Although there is an internal risk that these rituals will not be completed and will fail, or that there will be deviations from the ‘norm’ such as that performers will not behave according to the rules, these un-prescribed failures or deviations are rarely advertised, rather it is the success and the end result (in the rituals in which there is one) that is usually stressed, especially to outsiders or non-performers.

This distinction offers an insight into the Minoan sport of bull leaping. Bull leaping is widely depicted in Minoan iconography, and is found in most of the Minoan iconographic media: seals and signet rings, three-dimensional clay figurines, gold cups, stone vessels and wall-paintings. A considerable amount of scholarship has been dedicated to this subject, and it is not our aim to review it here (MacGillivray 2000, 53-55; Papageorgiou, forthcoming; Mavroudi). Bull leaping is widely recognised as a Minoan ritual, yet one of its most important characteristics is that it sometimes fails, and this failure is glorified, i.e. it is recorded in art. For example in the so-called Boxer’s Rhyton (Koehl 2006, frontispiece, p.i), a bull leaper is gored to presumably death by the horns of a bull, and others are trampled by bulls. This is a clear intrinsic failure on the part of the performer, in that the performance of a successful jump over the bull has failed. The fact that this, apparently mortal, failure has been advertised through art, but also that this is a difficult, particularly risky physical activity that requires an enormous amount of skill, strength and practice, point to the interpretation that this is indeed a sport and not a ritual. It may belong to a ritual package which may include the capture of the bull, bull leaping and perhaps sacrifice (Kyriakidis 2002, 78-80; Papageorgiou) but the activity of bull leaping itself seems to be a sport.

By contrast, other depictions in Minoan art may be ritual, such as the offerings to the seated lady (see Rehak 2000, 169-276), or processions (Papageorgiou) such as that depicted on the ‘Sacred Grove’ fresco from Knossos. The most prominent depiction of offerings to a seated lady is attested in Xeste III at Akrotiri (Doumas 1992, fig. 122) in which a blue monkey offers saffron gathered by ladies to the seated lady. In no depiction of offerings to a seated lady do we have any hints of failure.

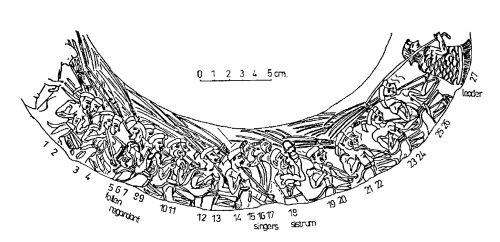

In procession scenes however we do have depictions of deviations from the ‘norm’. In the West ‘Sacred Grove’ fresco (Davis 1987, 157-161) at Knossos, several women are depicted in procession. There, some of the women assume the same stance, whereas a number of others are depicted as either not assuming the ‘prescribed’ position, or even turning back to look at the others. Neither of these, however, constitute failure but mere deviation, despite the fact that not all women seem to fully follow the ‘rule’. The same is the case in the Harvester’s Cup Rhyton (Herakleion Museum stone finds number 184; Warren 1969, 88, 174-176, 178-181; fig 3, 4). In this depiction, all men seem to be marching in a rhythm following the music of a double wind instrument and three singers. All figures move in exactly the same fashion, almost with military discipline, with one exception. He probably lost his pace and fell down distracting the man in front who turns to look what happened. His failure to march does not constitute ritual failure (except as far as he is concerned), as all the others are marching successfully and the procession continues.

Both occasions of ritual deviation in Minoan art as well as the failure to jump over the bull in the sport of bull-leaping are one aspect of Minoan naturalism in art in that they demonstrate the depiction of real events rather than of merely idealised scenes. And they remind the viewer that rituals may easily drift from the prescribed performance. They also remind us that bull-leaping is a very dangerous sport (and not a ritual).

In Minoan art therefore, as elsewhere, rituals are depicted as having risks. These depictions, as they appear there however, do not feature ritual failure but rather ritual deviation, i.e. minor deviations from the rule-governed norm. Thus, rituals do have uncertainties and risks of various kinds, both extrinsic and intrinsic. That are starker in the perception of the performer than that of the observer. In institutionalised rituals that are managed by a group of people, this uncertainty is also managed, since it constitutes one of the common effects of rituals, i.e. it enhances learning. Through Minoan art we can see that in Minoan rituals this uncertainty is shown only when it does not put into doubt the success of rituals. Outsiders should never know, after all, that ritual failure is an option.

References

- Austin, J. 1962. How to do Things with Words, Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bell, C. 1997. Ritual Perspectives and Dimensions, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bell, C. 2008. Response: Defining the need for a definition, in: Kyriakidis E. (ed.). The Archaeology of Ritual, Los Angeles CA: The Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Publications, 277-288.

- Brabham, D. 2008. Crowdsourcing as a Model for Problem Solving: An Introduction and Cases. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 14/1, 75-90.

- Chao, E. 1999. The maoist Shaman and the Madman: Ritual Bricolage, Failed Ritual, and Failed Ritual Theory, Cultural Anthropology 14/4, 505-534.

- Davis, E. 1987. The Knossos Miniature Frescoes and the Function of the Central Courts, in: R. Hägg and N. Marinatos (eds.). The Function of the Minoan Palaces. Proceedings of the Fourth International Symposium at the Swedish Institute in Athens, 10-16 June, 1984. [Swedish Institute in Athens, Series in 4°, 35] Stockholm: Skrifter Utgivna av Svenska Instituet i Athen, 157-161.

- Dayan, P. and Yu,A. 2003. Uncertainty and learning, Neuroscience 49/2, 171-181.

- Doumas, C. 1992. The Wall-Paintings of Thera. Athens: The Thera Foundation, Petros M. Nomikos.

- Flad, R. 2008. Divination and Power, A Multiregional View of the Development of Oracle Bone Divination in Early China. Current Anthropology 49/3, 403-437.

- Grimes, R. 1996. Infelicitous Performances and Ritual Criticism, in: Grimes, R. (ed.). Readings in Ritual Studies. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 279-293.

- Hüsken, U. 2007 (ed.). When Rituals Go Wrong: Mistakes, Failure, and the Dynamics of Ritual, Boston MA: Brill.

- Kamin, L. 1969. Predictability, surprise, attention, and conditioning, in: Campbell, B. and Church, R. (eds.). Punishment and Aversive Behavior, New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 242-259.

- Koehl, R. 2006. Aegean Bronze Age Rhyta, Philadelphia PA: INSTAP Academic Press.

- Kyriakidis, E. 2002. Ritual and its Establishment: the case of some Minoan Open-Air Rituals, PhD University of Cambridge.

- Kyriakidis, E. 2005. Ritual in the Aegean: the Minoan Peak Sanctuaries, London: Duckworth.

- Kyriakidis, E. 2008. The Archaeologies of Ritual, in: Kyriakidis, E. (ed.). The Archaeology of Ritual, Los Angeles CA: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Publications, 289-306.

- Kyriakidis, E. Ritual, Games and Learning, in: Renfrew, C., Morely, I. and Boyd, M.J. (eds.). Play, ritual and belief in animals and early human societies.

- Lett, J. 1990. Emics and Etics: Notes on the Epistemology of Anthropology, in: Headland, T., Pike, K. and Harris M. (eds.). Emics and Etics. The Insider/ Outsider Debate (Frontiers of Anthropology vol. 7, Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, 127-42.

- MacGillivray, J.A. 2000. Labyrinths and Bull-Leapers. Archaeology 53/6, 53-55.

- Marcus, J. 2006. The roles of ritual and technology in Mesoamerican water management, in: Marcus J. and Stanish, C. (eds.). Agricultural Strategies, [Monograph 50] Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Publications, 221-254.

- Mavroudi, N. 2011. Άνδρες, γυναίκες και ένας… πίθηκος στην κρητική εικονογραφία της Εποχής του Χαλκού. Proceedings of the 11th Cretological Conference.

- Michaels, A. 2007. Perfection And Mishaps In Vedic Rituals, in: Hüsken, U. (ed.). When Rituals Go Wrong: Mistakes, Failure, and the Dynamics of Ritual, Boston MA: Brill, 121-132.

- Nikolaidou, M. 2008. Ritualised Technologies in the Aegean Neolithic? The Crafts of Adornment, in: Kyriakidis E. (ed.). The Archaeology of Ritual, Los Angeles CA: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Publications, 221-254.

- Papageorgiou, I. 2011. Η προπαγάνδα της εικόνας: Χώροι εισόδου σε δημόσια αιγαιακά κτήρια της Ύστερης Εποχής του Χαλκού και ο συναφής τοιχογραφικός διάκοσμος,Proceedings of the 11th Cretological Conference.

- Pearce, J. and Hall, G. 1980, A model for Pavlovian learning: Variation in the effectiveness of conditioned but not unconditioned stimuli. Psychological Review 87, 532-552, 1980.

- Peters, F. 1985. Jerusalem: The Holy City in the Eyes of Chroniclers, Visitors, Pilgrims and Prophets from the Days of Abraham to the Beginning of Modern Times. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Rehak, P. 2000. The Isopata Ring and the Question of Narrative in Neopalatial Glyptic, in: Müller, W. and Pini, I. (eds.). Minoisch-mykenische Glyptik: Stil, Ikonographie, Funktion. V. Internationales Siegel-Symposium Marburg, 23-25 September 1999, Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag, CMS Beiheft, 269-276.

- Schieffelin, E. 1996. On Failure and Performance. Throwing the Medium out of the Seance, in: Laderman, C. and Roseman, M. (eds.). The Performance of Healing, London: Routledge, 59-89.

- Schieffelin, E. 2007. Introduction, in: Hüsken, U. (ed.). When Rituals Go Wrong: Mistakes, Failure, and the Dynamics of Ritual, Boston MA: Brill, 1-20.

- Warren, P. 1969. Minoan Stone Vases, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chapter 8 (155-163) from Ritual Failure: Archaeological Perspectives, edited by Vasiliki G. Koutrafouri and Jeff Sanders (Sidestone Press, 01.03.2018), published by OAPEN under the terms of an Open Access license.