Introduction

In England, several political changes in the 12th and 13th centuries helped to weaken feudalism. A famous document known as Magna Carta, or Great Charter, dates from this time. Magna Carta was a written legal agreement that limited the king’s power and strengthened the rights of nobles. As feudalism declined, Magna Carta took on a much broader meaning and contributed to ideas about individual rights and liberties in England.

The terrible disease was the bubonic plague, or Black Death. The plague swept across Asia in the 1300s and reached Europe in the late 1340s. Over the next two centuries, this terrifying disease killed millions in Europe. It struck all kinds of people—rich and poor, young and old, town dwellers and country folk. Almost everyone who caught the plague died within days. In some places, whole communities were wiped out. The deaths of so many people led to sweeping economic and social changes.

Lastly, between 1337 and 1453, France and England fought a series of battles known as the Hundred Years’ War. This conflict changed the way wars were fought and shifted power away from feudal lords to monarchs and the common people.

How did such different events contribute to the decline of feudalism? Read on.

Political Developments in England

Overview

There were many reasons for the decline of feudalism in Europe. In one country, England, political developments during the 12th and 13th centuries helped to weaken feudalism. The story begins with King Henry II, who reigned from 1154 to 1189.

Henry II’s Legal Reforms

Henry made legal reform a central concern of his reign. For example, he insisted that a jury formally accuse a person of a serious crime. Cases were then tried before a royal judge. In theory, people could no longer simply be jailed or executed for no legal reason. There also had to be a court trial. These reforms strengthened the power of royal courts at the expense of feudal lords.

Henry’s effort to strengthen royal authority led to a serious conflict with the Catholic Church. In the year 1164, Henry issued the Constitutions of Clarendon, a document that he said spelled out the king’s traditional rights. Among them was the right to try clergy accused of serious crimes in royal courts, rather than in Church courts.

Henry’s action led to a long, bitter quarrel with his friend, Thomas Becket, the archbishop of Canterbury. In 1170, four knights, perhaps seeking the king’s favor, killed Becket in front of the main altar of Canterbury Cathedral. The cathedral and Becket’s tomb soon became a popular destination for pilgrimages. In 1173, the Catholic Church proclaimed him a saint. Still, most of the Constitutions of Clarendon remained in force.

King John and Magna Carta

In 1199, Henry’s youngest son, John, became king of England. John soon made powerful enemies by losing most of the lands the English had controlled in France. He also taxed his barons heavily and ignored their traditional rights, arresting opponents at will. In addition, John quarreled with the Catholic Church and collected large amounts of money from its properties.

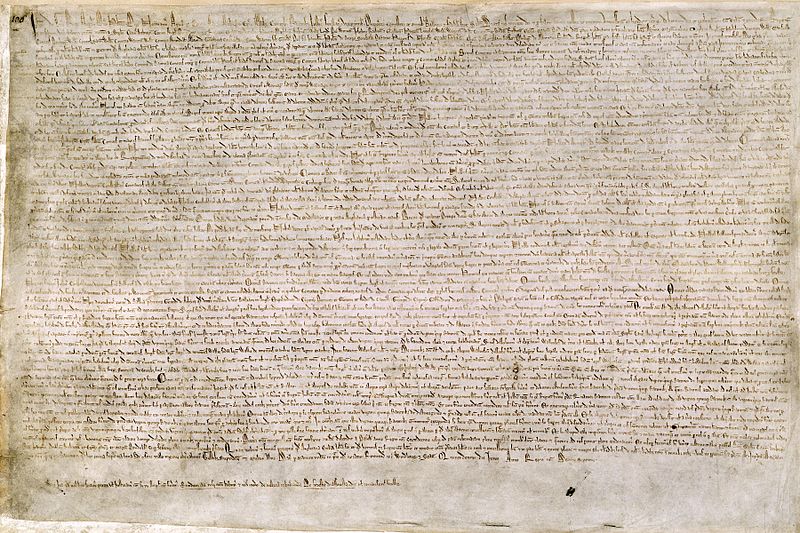

In June 1215, angry nobles forced a meeting with King John in a meadow called Runnymede, beside the River Thames, outside of London. There, they insisted that John put his seal on a document called Magna Carta, which means “Great Charter” in Latin.

Magna Carta was an agreement between the nobles and the monarch. The nobles agreed that the monarch could continue to rule. For his part, King John agreed to observe common law and the traditional rights of the nobles and the Church. For example, he promised to consult the nobles and the Church archbishops and bishops before imposing special taxes. He also agreed that “no free man” could be jailed except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land. This idea eventually developed into a key part of English common law known as habeas corpus (HAY-be-us KOR-pus).

In many ways, Magna Carta only protected the rights and privileges of nobles. However, as time passed, the English people came to regard it as one of the foundations of their rights and liberties.

King Edward I and the Model Parliament

In 1295, Edward I, King John’s grandson, took a major step toward including more people in government. Edward called together a governing body called the Model Parliament. It included commoners and lower-ranking clergy, as well as high-level Church officials and nobles.

The Impact of Political Developments in England

These political changes contributed to the decline of feudalism in two ways. Some of the changes strengthened royal authority at the expense of the nobles. Others weakened feudalism by eventually shifting some power to the common people.

Magna Carta established the idea of rights and liberties that even a monarch cannot violate. It also affirmed that monarchs should rule with the advice of the governed. Henry II’s legal reforms strengthened English common law and the role of judges and juries. Finally, Edward I’s Model Parliament gave a voice in government to common people, as well as to nobles. All these ideas formed the basis for the development of modern democratic institutions.

The Bubonic Plague

Overview

You have learned how political developments in England helped to weaken feudalism in that country. Another reason for the decline of feudalism was the bubonic plague, which affected all of Europe. The bubonic plague first struck Europe from 1346 to 1351. It returned in waves that occurred about every decade into the 15th century, leaving major changes in its wake.

Historians think the plague began in Central Asia, possibly in China, and spread throughout China, India, the Middle East, and then Europe. The disease traveled from Central Asia to the Black Sea along the Silk Road (the main trade route between Asia and the Mediterranean Sea). It probably was carried to Italy on a ship. It then spread north and west, throughout the continent of Europe and to England.

The Black Death

Symptoms, or signs, of the plague included fever, vomiting, fierce coughing and sneezing fits, and egg-sized swellings or bumps, called buboes. The term “Black Death” probably came from these black-and-blue swellings that appeared on the skin of victims.

The dirty conditions in which people lived contributed significantly to the spread of the bubonic plague. The bacteria that cause the disease are carried by fleas that feed on the blood of infected rodents, such as rats. When the rats die, the fleas jump to other animals and people. During the Middle Ages, it was not unusual for people to go for many months without a change of clothing or a bath. Rats, covered with fleas, often roamed the floors of homes looking for food. City streets were filled with human waste, dead animals, and trash.

At the time, though, no one knew where the disease came from or how it spread. Terrified people falsely blamed the plague on everything from the positions of the planets to lepers and to Jews.

Persecution of the Jews did not begin with the plague. Prejudice against Jews had led the English government to order all Jews to leave the country in 1290. In France, the same thing happened in 1306 and again in 1394. But fear of the plague made matters worse. During the Black Death, many German cities ordered Jews to leave.

The Impact of the Plague

The plague took a terrible toll on the populations of Asia and Europe. China’s population was reduced by nearly half between 1200 and 1393, probably because of the plague and famine. Travelers reported that dead bodies covered the ground in Central Asia and India.

Some historians estimate that 24 million Europeans died of the plague—about a third of the population. The deaths of so many people speeded changes in Europe’s economic and social structure, which contributed to the decline of feudalism.

Trade and commerce slowed almost to a halt during the plague years. As Europe began to recover, the economy needed to be rebuilt. But it wouldn’t be rebuilt in the same way, with feudal lords holding most of the power.

After the plague, there was a shift in power from nobles to the common people. One reason for this was a desperate need for workers because so many people had died. The workers who were left could, therefore, demand more money and more rights. In addition, many peasants and some serfs abandoned feudal manors and moved to towns and cities, seeking better opportunities. This led to a weakening of the manor system and a loss of power for feudal lords.

After the plague, a number of peasant rebellions broke out. When nobles tried to return things to how they had been, resentment exploded across Europe. There were peasant revolts in France, Flanders, England, Germany, Spain, and Italy.

The most famous of these revolts was the English Peasants’ War in 1381. The English rebels succeeded in entering London and presenting their demands to the king, Richard II. The leader of the rebellion was killed, however, and after his death, the revolt lost momentum. Still, in most of Europe, the time was coming when serfdom would end.

The Hundred Years’ War

Overview

Between 1337 and 1453, England and France fought a series of battles for control over lands in France. Known as the Hundred Years’ War, this long conflict contributed to the erosion of feudalism in England and in France.

English monarchs had long claimed lands in France. This was because earlier English kings had actually been feudal lords over these French fiefs. French kings now disputed these claims. When Philip VI of France declared that the French fiefs of England’s King Edward III were part of Philip’s own realm, war broke out in France.

Early English Successes

Despite often being outnumbered, the English won most of the early battles of the war. What happened at the Battle of Crécy (KRAY-see) shows why.

Two quite different armies faced each other at the French village of Crécy in 1346. The French had a feudal army that relied on horse-mounted knights. French knights wore heavy armor, and they could hardly move when they were not on horseback. Their weapons were swords and lances. Some of the infantry, or foot soldiers, used crossbows, which were effective only at short ranges.

In contrast, the English army was made up of lightly armored knights, foot soldiers, and archers armed with longbows. Some soldiers were recruited from the common people and paid to fight.

The longbow had many advantages over the crossbow. Larger arrows could be fired more quickly. The arrows flew farther, faster, and more accurately, and could pierce the armor of the time. At Crécy, the longbow helped the English defeat the much larger French force.

The French Fight Back

The French slowly chipped away at the territory the English had won in the early years of the war. In 1415, after a long truce, English King Henry V again invaded France. This time, the English met with stronger resistance. One reason was that the French were now using more modern tactics. The French king was recruiting his army from commoners, paying them with money collected by taxes, just as the English did.

Another reason for increased French resistance was a new sense of national identity and unity. In part, the French were inspired by a 17-year-old peasant girl, known today as Joan of Arc. Joan claimed that she heard the voices of saints urging her to save France. Putting on a suit of armor, she went to fight.

In 1429, Joan led a French army to victory in the Battle of Orléans (OR-lay-uhn). The next year, the “Maid of Orléans” was captured by English allies. The English pushed certain Church leaders to accuse Joan of being a witch and a heretic and to burn her at the stake.

Joan of Arc’s heroism changed the way many French men and women felt about their king and nation. Twenty-two years after Joan’s death, the French finally drove the English out of France. Almost 500 years later, the Roman Catholic Church made Joan a saint.

The Impact of the Hundred Years’ War

The Hundred Years’ War contributed to the decline of feudalism by helping to shift power from feudal lords to monarchs and to common people. During the struggle, monarchs on both sides had collected taxes and raised large professional armies. As a result, kings no longer relied as much on nobles to supply knights for the army.

In addition, changes in military technology made the nobles’ knights and castles less useful. The longbow proved to be an effective weapon against mounted knights. Castles also became less important as armies learned to use gunpowder to shoot iron balls from cannons and blast holes in castle walls.

The new feeling of nationalism also shifted power away from lords. Previously, many English and French peasants felt more loyalty to their local lords than to their monarch. The war created a new sense of national unity and patriotism on both sides.

In both France and England, commoners and peasants bore the heaviest burden of the war. They were forced to fight and to pay higher and more frequent taxes. Those who survived the war, however, were needed as soldiers and workers. For this reason, the common people emerged from the conflict with greater influence and power.

The Trials of Joan of Arc

Overview

In 1429, a teenage girl named Joan of Arc helped a prince to become king of France. Joan lived at a time when the feudal system in Europe was beginning to weaken. How did Joan’s extraordinary life show that new ways were about to replace old traditions in Europe?

The visions and the voices came without warning, like a flash of lighting. In 1425, Joan of Arc, the daughter of northern French peasants, had just turned 13. Until then, she had had a normal childhood. She attended mass regularly and prayed frequently to God.

Then the voices and visions started. Saints Michael, Catherine, and Margaret suddenly came to her. “I was terrified,” Joan remembered later. “There was a great light all about.” But soon she was reassured by the sweet, kind voices and stopped being afraid.

Joan lived in a religious time. It wasn’t unheard of for people to report that saints spoke to them. But Joan’s voices set her a daunting task. They directed her to help Charles, the dauphin (DOE-fehn), or French heir to the throne, to become king. They also wanted her to free France from the English, who had conquered parts of the country.

France in Chaos

The year when Joan’s voices started, France was in chaos. Since 1337, the English and French had been fighting the Hundred Years’ War. In 1420, English king Henry V took the French throne. When Henry died in 1422, the dauphin Charles insisted that he, and not Henry’s infant son, was the rightful king. His claim led to even bloodier fighting between the English and French.

France itself was deeply divided. The feudal lords of the powerful province of Burgundy helped the English seize northern France. Those loyal to Charles controlled the southern half of the country. Even though Charles was the dauphin, he hadn’t been crowned.

Since the 11th century, all French kings had been crowned in Reims (RAHNZ), but the English controlled land around the city. However, Joan’s voices told her that she should lead Charles to Reims and see that he was crowned king.

A Journey to Find a King

At the age of 17, Joan set out to find Charles. It was dangerous for a female to travel alone, so she disguised herself by cutting her hair and putting on men’s clothing. Without telling her parents, she rode to a nearby fort to ask the commander for soldiers to protect her.

When she reached the fort, the commander just laughed at her request. But Joan soon convinced him, and he ordered a group of soldiers to ride with her. On February 13, 1429, they set out for Charles’ court at Chinon (shee-NOHN).

Charles heard she was on her way. He had heard prophecies, or predictions, that this young peasant woman would rescue France from the English. When she arrived at Chinon, Charles tested Joan’s claims by disguising himself. Court officials introduced another man to Joan as the dauphin. However, Joan immediately picked out Charles from the crowd. She knelt before and announced, “Very noble Lord dauphin, I am come and sent by God to bring succor [help] to you and your kingdom.” Charles agreed that God had sent Joan to save France.

The Battle to Free Orléans

Joan’s first challenge on the way north to Reims was to free the city of Orléans (OR-lay-uhn). Charles had a suit of armor made for her, but she still needed a sword. She predicted that priests would find one for her in a nearby church. Sure enough, they dug behind the altar and found a sword. She also had a banner made. Armed with her sword and carrying her banner, Joan filled the French with hope.

In the spring of 1429, Joan led Charles’s troops toward Orléans, which the English had had under siege for six months. The French feared that if they lost that city, they would lose all of France. On May 4, Joan led the French troops into battle for the first time.

At a monastery near Orléans held by the English, French soldiers attacked. They were on the verge of defeat when Joan suddenly galloped into the battle, carrying her banner and flashing her sword. Inspired, the French soldiers soon overwhelmed the English.

Three days later, the French attacked Orléans itself. In the middle of the battle, Joan was hit by an arrow. Grimacing with pain, she pulled the arrow out, and threw herself back into the fight. She then led French troops across a moat and stormed the city’s walls. The French soon poured into Orléans, and the English beat a rapid retreat.

After the victory, thirty thousand grateful residents of Orléans cheered Joan as she road with her soldiers through the streets. Forever after, she would be known as the “Maid of Orléans.” In the following weeks, Joan’s forces freed more surrounding towns from the English.

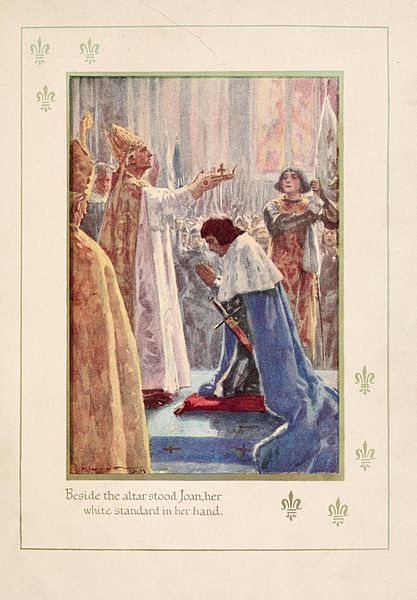

Crowning King Charles VII

After these victories, Joan returned to Charles and persuaded him to travel to Reims to be crowned. At last, on July 17, 1429, with Joan at his side, the dauphin became King Charles VII. After the coronation, Joan burst into tears of joy.

Unfortunately, the coronation proved to be the high point for Joan. Charles started to distance himself from her, perhaps fearing her enormous popularity. In the fall of 1429, Charles and Joan led troops toward Paris, which the English and their allies controlled. But on his own, Charles reached a ceasefire agreement with the Duke of Burgundy. When Joan learned about it, she was outraged. She had wanted to fight to free Paris. “I am not satisfied with this manner of truce,” she fumed.

Joan’s Capture

Meanwhile, French troops, now with a king to follow and tired of fighting, were deserting Joan’s army. In May 1430, Burgundy’s army of 6,000 soldiers prepared to attack Compiègne (komp-YANE), a French-held town near Paris. Joan’s army had only 300 soldiers. At five in the evening, she launched a surprise attack.

At first, the French held their own, but thousands of English soldiers soon joined the battle. The French were forced to retreat to Compiègne. When the town’s mayor saw English troops approaching, he closed the drawbridge, trapping Joan outside. The Burgundians captured her and threw her into prison. Charles made no effort to rescue or ransom the woman to whom he owed so much. After several months, the English paid the Burgundians a huge ransom for her.

On Trial for Her Life

The English and the Catholic Church put Joan on trial in Rouen (ROO-ehn) for witchcraft and for heresy, or spreading beliefs that violate accepted religious teachings. They hoped that by proving that God did not guide Joan they could undermine Charles VII’s right to the French throne. Bishop Pierre Cauchon, an ally of the English, led the proceedings. When the trial started in February 1431, Joan boldly warned the bishop, “You say that you are my judge. Take thought over what you are doing. For, truly, I am sent from God, and you are putting yourself in great danger.”

The warning did not stop Bishop Cauchon from drilling Joan with questions, such as, “Did God command you to put on men’s clothing?” Joan responded, “I did not put on this clothing, or do anything else, except at the bidding of God and the angels.” Ordinary people watching the trial loved Joan’s courageous answers. She was following her conscience and standing up to the bishop and to the English.

The court made 70 accusations against Joan. In May, to save her life, she signed a confession. But after a few days, she took it back, saying, “What I said, I said for fear of the fire.” She had made the brave decision to stay true to her beliefs—even though she faced execution.

A huge crowd gathered in Rouen on May 30, 1431, to watch Joan be burned at the stake, a common death sentence for heretics and witches. Through her horrible ordeal, she showed great courage.

Charles VII remained king for 40 years, forced the English out of France, and united the country. During that time, Joan’s life became a legend.

In 1455, Joan’s family asked the pope to reopen her case, and Joan was found innocent of all charges. In 1920, Joan was made a Catholic saint. Today, Saint Joan is one of the most beloved of French heroes, the patron saint of the nation and of its soldiers. She inspired her country and helped to restore the throne to a French king. She also proved that women could be brave and effective leaders. Finally, her remarkable life shows that with faith, courage, and determination someone from ordinary beginnings can make history.

Originally published by Flores World History, free and open access, republished for educational, non-commercial purposes.