Seeking out their underlying meanings.

By Dr. Susan Boynton

Professor of Music, Historical Musicology

Columbia University in the City of New York

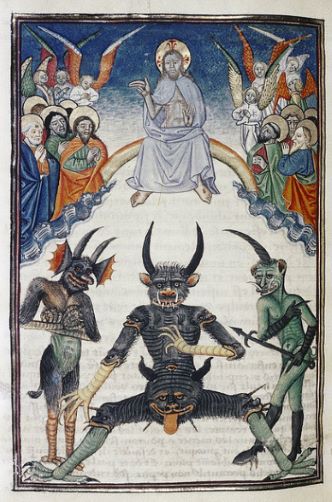

The manifold appearances of demons and the Devil are central themes in the monastic literature of the eleventh, twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Just as a more general fascination with the diabolical infuses medieval visual culture with grotesque or startling images,1 a more specific instance of this preoccupation produced texts in which demonic interventions interfere and sometimes even intersect with the central activity of monastic life: the divine office. Of the eight daily services that comprised the liturgy of the hours, the one most often favoured with demonic visitations seems to have been matins, perhaps because it was performed in the very early hours of the morning, a time we would now consider the middle of the night.2 The abundance of stories about the difficulty of rising for matins suggests that it could be a struggle just to get out of bed and to reach the church at all, not to speak of staying awake during the service. Somnolent monks might well have imagined dimly visible figures in the shadows of the choir, which were dispersed only by a few candles except on major feasts of the church year, when there was extra illumination.3 In addition to a potentially causal relationship between the embodied experience of the monastic night office and the idea of diabolical influence, we should keep in mind the highly symbolic character of monastic discourse and of commentary on the liturgy, neither of which is ever purely descriptive. Even narratives with obvious implications can express concerns beyond the immediate matter at hand, bringing out latent conflicts in the community or more generally serving to reinforce the writer’s underlying purpose.

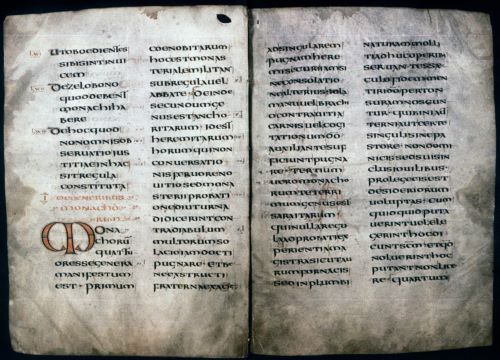

To understand monastic texts about demonic intervention in the liturgy as more than just entertaining tales, then, one must seek out their underlying meanings. The night office not only provided ideal conditions for the creation of phantasms, but also functioned as the centre of gravity of the monastic liturgy, indeed its defining moment. Many of the texts and melodies of matins were distinctive, varying from church to church, making this office a particularly detailed reflection of a community’s corporate identity.4 In the eleventh and twelfth centuries, monastic reformers increasingly turned their attention to the divine office, stressing the proper execution of the readings and chants, and in some cases revising chant texts and melodies to make them conform to notions of authenticity.5

This historical context provides a useful framework for interpreting the longstanding topoi of angelic presence and demonic intervention in the monastic liturgy. These are common themes in medieval commentary on the liturgy, and by the central middle ages they had a long history in monastic writings going back to the Desert Fathers and to early western monasticism.6 The monastic imaginary also created narratives about angelic presence in the divine office, forming a parallel to those about the threats from evil beings. For instance, the sixth-century Rule of the Master states that during prayer, frequent coughing, spitting and throat-clearing are manifestations of the Devil’s attempts to impede prayers and psalmody. When blowing his nose, a monk should project the contents behind him on account of the angels that were arrayed invisibly in front of him. The Master then cites the beginning of psalm 137, ‘In the sight of angels I will sing to you’, concluding ‘Therefore you see that we are shown as praying and singing before angels’. But the presence of angels is not enough. The Master continues that prayer should be brief to prevent dozing while lying on the ground (in the performance of psalmody described by the Rule of the Master, each psalm was followed by silent prayer performed in a completely prostrate position). The Devil could bring something extraneous before a monk’s eyes or insinuate it into his heart.7

The Rule of Benedict’s chapter on psalmody also affirms the presence of the divine: ‘We believe that the divine presence is everywhere … we should believe this to be especially true when we celebrate the divine office’. Like the Rule of the Master, the Rule of Benedict quotes the first verse of psalm 137, concluding ‘Let us consider, then, how we ought to behave in the presence of God and his angels, and let us stand to sing the psalms in such a way that our minds are in harmony with our voices’.8 As Giles Constable has pointed out, the correspondence between voice and mind in prayer was well established in Christian antiquity, also finding expression in the Rule of the Master’s prescription to ‘sing together in voice and in mind’.9 While the Rule of Benedict and the Rule of the Master share this emphasis in their chapters on the discipline of psalmody, they differ in the extent to which they refer to demonic influence. The Rule of Benedict’s exposition of psalmody makes no reference to the Devil. Indeed, Benedict hardly mentions the Devil, except in the chapter on entry into the monastery, where it is stated that a newly professed monk’s lay clothing is taken away from him and stored so that if he should ever agree to the Devil’s suggestion to leave the monastery, he can reclaim his lay attire upon departure.10

These references to the Devil in the Rule of the Master and the Rule of Benedict draw upon the thematics of diabolical temptation that had already been established by late antique textual traditions such the lives and sayings of the Desert Fathers. The Apophthegmata Patrum, a fifth-century compilation of Greek aphorisms and anecdotes associated with the early monks of the Egyptian desert, contains numerous references to the ever-present threat of the Devil and demons, often in the form of temptation, such as pride, that the individual must vanquish through sincere humility. Since the earliest texts concern hermits who rarely gathered for worship, the Apophthegmata Patrum contains few allusions to communal liturgy. In one significant anecdote, however, the Devil attempts to prevent a monk from attending the Sunday synaxis by telling him that the bread and wine is not really the body and blood of Christ. When the deluded monk fails to appear in church, the other monks become concerned, seek him out, and set him straight, with the ultimate result that he overcomes the deception of the Devil and celebrates the Eucharist in community with the others.11

While some monastic writings of the central and high middle ages similarly invoke the Devil as a ubiquitous yet intangible threat, others contain vivid, even graphic descriptions of demons in all their diverse manifestations.12 Some of the most prolix and precise visualizations depict demonic agency in the monastery, and particularly in the divine office, in terms that are as concrete as they are symbolic. Such anecdotes reify in narrative the longstanding belief in the constant threat of temptation and pride that was represented by the presence of evil influences in the monastery.

The eleventh-century monk Radulfus Glaber’s Histories present a multitude of demons with differing appearances who act independently in various settings.13 In the fifth book Radulfus describes three close encounters with a demon that occur in different locations but all around the hour of matins. These three anecdotes are linked mainly by the time of their occurrence and the fact that Radulfus himself is their protagonist. They are preceded by a pre-existing tale about a demon who appeared to a monk when the bell rang for matins and distracted him so much that the hapless monk missed the office altogether.14 In the first of Radulfus’s first-person narratives, he recounts that before matins, at St.-Léger de Champceaux, a small, ugly man spoke to him from the foot of his bed.15 The second sighting was after matins, at dawn in the dormitory of Radulfus’s own community, St. Bénigne at Dijon.16 The third was in the priory of Moutiers-Sainte-Marie, when Radulfus failed to go to matins at the sound of the bell. Once the other monks had hastened to the church, the same creature ascended the dormitory stairs and paused, out of breath, declaring ‘It is I, it is I who stay with those who remain’.17

Although none of these visitations takes place during the office, it is significant that they happen around the office. Radulfus’s account is both deeply symbolic and oddly realistic, because his descriptions convey something of the everyday reality of the morning routine of rising for matins, interpreted in some monastic writings as signifying casting off sleep, and therefore sin, to espouse wakefulness, meaning salvation.18 The demonic presence has an extraliturgical effect as well – following the last two appearances recounted by Glaber a monk fled the monastery to live briefly in the world before finally returning to the community.

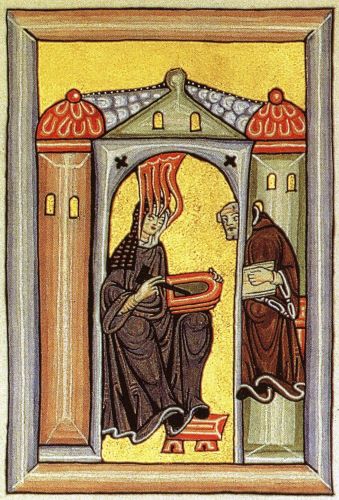

Departure from the monastery at the instigation of the Devil, which was mentioned in the Rule of Benedict, also appears in a more overtly allegorical monastic text of the late twelfth century, Hildegard of Bingen’s musical morality play, the Ordo Virtutum. Here a young soul, Anima, perhaps representing a novice or at least a younger member of a monastic community, starts out happy, but later desires to shed her garment, which could be interpreted as the monastic habit. The personification of Knowledge of God sings to Anima: ‘Look at what you are wearing, daughter of salvation: be steadfast and you will never fall’. In response, Anima laments ‘I don’t know what to do or where to flee. Alas, I cannot fulfil what I am wearing. In fact, I want to cast it off’.19 The Devil leads Anima astray, but she soon longs to return to the community, and Virtues welcome her back despite her intransigence, addressing her as a fugitive.20 The soul laments her weakness and supplicates the help of the Virtues, who triumph over the Devil and return the lost soul to the fold. Both the Devil’s role in this scenario and the references to clothing recall the prescription in the Benedictine Rule regarding the change of clothing upon departure from the monastery at the instigation of the Devil. The Devil clearly represents the interference of the outside world in the life of the monastic community. He is the only character in the Ordo Virtutum who speaks instead of singing, with the result that his lines are the only ones in the manuscript of the play that lack musical notation.

The portrayal of the Devil as a being without music perfectly illustrates Hildegard’s conception of the role of music in the monastic community as set forth in her epistle 23 to the clergy of Mainz, who had placed an interdict on the convent of Rupertsberg because of an excommunicate buried in its graveyard. For the period of the interdict, the nuns were forbidden to receive communion or sing the divine office.21 Hildegard’s letter refers to the Devil’s schemes to disrupt musical praise of the divine, aptly yet subtly conveying the underlying point that the interdict furthered the work of the Devil.22 As an explicit presentation of Hildegard’s theology of music, this letter illuminates the meaning of the Ordo Virtutum. According to the letter, the life of a monastic community centres on singing the divine office, which the Devil seeks to impede; likewise, in the Ordo Virtutum the Devil temporarily interpolates his tuneless speech into the previously harmonious world of the monastery. When the choir of the Virtues overwhelms him, the community regains musical integrity and the symbolic order is restored. With Anima back in the fold, the voice without music is banished conclusively. The significance of singing in the Ordo Virtutum reflects both the lived experience of the daily liturgical round and Hildegard’s ideal of the monastery as a sonic community.23

Like Hildegard of Bingen, Peter the Venerable, abbot of Cluny, was a twelfth-century Benedictine deeply concerned with religious reform, and in this regard it is no coincidence that he also wrote vividly about the ways in which demons prevented monks from taking part in the liturgy. The first book of Peter’s De Miraculis contains the story of a monk who customarily rang the bell for matins awakening one night with the impression that he has overslept because he can hear the sound of a bell. After finding no one in the church and then returning to his dormitory where all the other brothers are still asleep, he finally realizes that he has been deceived by demonic influence. Peter’s commentary concluding this chapter notes that monks should not wander freely about the monastery at night, as they can be misled by demons in such a way that a disturbed sleep pattern causes them to miss the night office altogether.24

These texts by Radulfus Glaber, Hildegard of Bingen and Peter the Venerable all portray the exercise of free will undermined by demonic or diabolical influence. In the Histories and the Ordo Virtutum, agents of evil take a physical form to draw their objects away from monastic observance without taking part in the divine office. In other words, the Devil and demons interfere with the liturgy in various ways but do not appear to enter the discursive space of the church itself; their intervention in worship is indirect, mediated by the actions of monks, nuns and secular clergy. In the Cistercian exemplum collections of the early thirteenth century, however, demons gain full access to the monks’ choir, in some cases becoming as much of a presence in the church as the angels who were thought to observe the services and occasionally to join in them. Cistercian narratives abound in colourful descriptions of the supernatural beings whose actions sometimes unfold in coordination with the divine office. Many stories depict demons witnessing and infiltrating the liturgical services they strive to disrupt. In several cases demons take on the role of an audience, appraising the performance verbally or expressing their approval of bad behaviour through enthusiastic cheers and applause.

Compilers of the exemplum collections were careful to frame these vivid stories with admonitions presenting the purpose and moral of each tale. The exempla are inherently didactic, employed in preaching and other forms of teaching.25 While the potential applications of exempla were numerous, the intended audience of the Cistercian collections included the novices of the order. Caesarius of Heisterbach, author of the Dialogus Miraculorum (completed by 1223), was novicemaster in his convent of Heisterbach, although Brian Patrick McGuire has argued that Caesarius’s travels and large literary output suggest that he did not hold the office continually.26 Nevertheless, both the presentation of the collection as a dialogue (albeit an artificial one) between a novice and his teacher and the fact that many of the stories concern novices make the Dialogus Miraculorum particularly instructive for that sector of the Cistercian population.27

The exempla containing stories that unfold during the night office convey their messages in various ways; some seem intended to reinforce good behaviour while others deliver explicit warnings of the perils of common failings. An anecdote in the twelfth-century Cistercian Collectaneum Exemplorum is entitled ‘How much care God and the Holy Angels have for those who take part in the offices purely’. In this exemplum a monk realizes that the unknown persons he saw in the choir one night sought to work mischief, because the following night he saw a terrifying demon enter the choir only to be expelled by an equally awesome angel.28

Many visions described in the exempla are far less reassuring. Another chapter in the Collectaneum relates that a monk saw the Devil in the guise of a monkey who enters the choir during the night office and ridicules sleeping monks by standing before them clapping his hands. The monk kept silent about his vision and witnessed it a second time, but it disappeared when he told others about it.29 A chapter in Conrad of Eberbach’s Exordium Magnum, a text from the beginning of the thirteenth century, begins by stating that the narrative illustrates the dangerous fantasies and illusions suffered by those monks who are so lukewarm in the service of God as to fall asleep in choir. The tale describes a monk who sees the angel of the Lord censing the choir and altar on Pentecost during the singing of the canticle at Lauds, Benedicite Omnia Opera (Daniel 3:57–88, 56). The angel places a burning coal in the monk’s mouth, causing him to fall ill and lie in the infirmary for three days as if dead. Recovered and back in the choir at matins, the monk witnesses a multitude of demons (invisible to the others) who seek to distract the other monks from worship, applauding those who are lazy or somnolent, and dumping filth on the sleepers so as to infuse their dreams with evil phantasms.30

In Cistercian exempla, demons not only seized upon the impulse to doze off during the night office but also symbolized other kinds of temptation, such as pride, continuing the tradition of diabolical incitement to pride seen in earlier monastic literature. Overweening pride in expert singing forms the central theme in a number of exempla. In the Dialogus Miraculorum of Caesarius of Heisterbach, one chapter in the distinctio on temptation describes a group of clerics in a secular church singing ‘loudly, not piously, and lifting tumultuous voices on high’.31 A religiosus who happens to be present sees a demon standing high up with a large sack that he filled with the voices of the singers, which he caught with his extended right hand. After the conclusion of the service, as the singers congratulated themselves upon their performance, the religiosus, who saw the demon, tells them: ‘You have indeed sung well but you have sung a sack full’.32 Although the story could be interpreted as privileging regular over secular clergy, the distinction between the singers and the religiosus is not made clear. More important is the striking description of the voices being captured and subverted to the demon’s own purposes.

Caesarius explicitly links this story to the distinctio on demons, stating ‘In the fifth chapter of the following distinction, you will hear how the raising of voices pleases [God]. There you will find how much demons rejoice if voices are lifted in psalmody without humility’.33 This exemplum is just one of several texts from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries that condemn the excesses of virtuosic singing that aggrandized the performers, a form of pride that writers decried as an intrusion of the values of secular entertainment into the liturgy. One of the most detailed passages of this kind was written by the twelfth-century Cistercian Aelred of Rievaulx, who vividly described a kind of singing that made use of abundant embellishments, bodily display, histrionic gestures and a style of vocal production deemed more feminine than masculine (and therefore unnatural). Aelred does not link mannered performance explicitly to the Devil or to demons but denounces it as ludicrous minstrelsy that belongs outside the church.34

Cistercian exempla frequently invoke a direct causal connection between misbehaviour in the choir (including musical mischief ) and the presence and even active involvement of demons. Just as Caesarius himself promises in the Distinctio on Temptation, a particularly remarkable concatenation of stories about demons in the monastic liturgy appears in the fifth chapter of the immediately following Distinctio on Demons, which recounts several demonic interventions during matins on feast days that fall in the month of November.35 According to this narrative, a conversus at the abbey of Hemmenrode often saw demons running through the choir at night. Hermann, a monk in the community, prayed for and received the ability to see such visions.36 During matins on the feast of St. Martin (11 November) he saw a demon in the form of a peasant enter next to the presbytery and stand in front of a novice. On the feast of St. Cunibert (12 November), Hermann saw two demons enter the presbytery and ascend the stall of the abbot between the choir of the monks and the novices. When they reached the corner, a third demon joined them, passing so close to Hermann that he could have touched them. The monk near whom the third demon had been standing is described as a lazy complainer who slept in the choir but sang grudgingly, happier to drink than to chant. Even the shorter night offices always seemed very long to him.37 Here the ubiquitous condemnation of slothfulness in the choir combines with pithy and fantastical description.

The same chapter of the Dialogus contains two anecdotes that represent the height of demonic participation in the liturgy. On the feast of St. Columban (23 November), as the prior intoned the first psalm of matins, Domine quid multiplicati sunt qui tribulant me, the demons on that side of the choir multiplied so that the brothers there made mistakes in the psalmody. When the choir on the opposite side attempted to correct them, the demons flew across and disrupted their psalmody by mixing in with the monks so that they did not know what they were singing; the two choirs ended up shouting at one another. Discord in the choir is not only a choir leader’s nightmare but also symbolizes a crisis in the internal order of the monastic community. The abbot and prior attempted in vain to remedy the situation but could not bring the singers back to the psalm tone or unite their dissonant voices. The Devil finally departed with his assistants and order returned to the choir.38

Demonic disruption of the choir was a serious threat because liturgical performance was a realization of the community’s social structure and hierarchy. Successful psalmody depends on the singers’ ability to listen to one another and to begin and end each phrase together. Even though medieval chant had no conductor in the modern sense and was sung in a more or less free rhythm, for those who perform chant often with the same people it is not difficult to maintain the integrity of the ensemble as long as everyone listens. Ambient darkness and imbalance among the voices can make it more difficult for singers to communicate effectively with one another, and are precisely the conditions that obtain in most of the Cistercian stories about demonic intervention.

In another anecdote within the same chapter of the Distinctio on demons, musical disorder seems to symbolize social disorder. One night at matins, the hebdomadarius (weekly cantor) sang the invitatory antiphon, and the monk near him then intoned the invitatory psalm 94, moderately – voci mediocri (probably signifying a combination of a moderate pitch and voice). As the choir of senior monks began to sing the psalm verse, a youth at the lower end of the choir found the intonation too low for his taste and sang the continuation of the psalm fully five tones higher, creating dissonance within his half of the choir (or possibly a form of parallel organum). The subprior resisted, but the youth persisted in raising the pitch of the choir on his side. When the other half of the choir sang the next verse, some followed the youth by singing at the same elevated pitch level, while others fell silent, scandalized. Then Hermann saw a demon move from the young monk to those in the opposite choir who had taken his part. Caesarius concludes this episode: ‘a humble song (humilis cantus) with devotion of the heart pleases God more than voices lifted arrogantly to heaven’.39

The idea of humility and devotion in chant was important to the Cistercians, who expressed it in their writings more often than the Benedictines. This peculiarly Cistercian tenet of moderation or mediocritas in singing appears in statute 75 of the twelfth-century institutes of the general chapter at Cîteaux:

It is fitting for men to sing with a manly voice, not imitating the frivolity [or lasciviousness] of minstrels in a feminine manner with shrill or (as is commonly said) false voices.And therefore we have decreed that moderation (mediocritas), be preserved in chant, so that it may be redolent of seriousness, and that devotion may be preserved.40

Chrysogonus Waddell situates this statute around 1147 when the reformed Cistercian antiphoner was promulgated. The association of high pitch with frivolity or wantonness is frequently invoked in Cistercian texts. For instance, a chapter in the Exordium Magnum sets forth the negative example of a monk blessed with a beautiful voice who stayed silent during festal matins throughout the choral chants in order to save himself for his big solo, the verse of a great responsory which he sang ‘extremely high, with his usual lasciviousness of voice’.41 At the end of his virtuosic performance, the monk was applauded enthusiastically by a small, very dark demon. Both the narrative and Conrad of Eberbach’s concluding comment borrow from the language of the statute of the general chapter stating that the moderation prescribed by the order and the authority of the rule teaches that monks must sing with humility both individually and together.42

In addition to the exempla, more practical writings on chant also illustrate the importance to the Cistercians of listening and singing together. Such pragmatic considerations form the substance of a short treatise written in the twelfth century and soon thereafter attributed to Bernard of Clairvaux. It begins with a passage echoing both the Rule of Benedict’s chapter on psalmody and the liturgical theology of the Cistercians: ‘Our venerable father Bernard, abbot of Clairvaux, ordered monks to maintain this manner of singing, affirming that it is pleasing to God and the angels’. The body of the text continues with admonitions for the technical execution of chant:

We should not draw out the psalmody too much, but we should sing with a round and full voice. We must start each half-verse and the end of each verse together and we must finish them together … No one may presume to begin before the others and hasten too much, or to drag along after the others too much or to hold the final cadence. We must sing together, we must pause together, always listening.43

The remainder of the text explains how soloists and choirs should perform the intonations and repetitions of chants, as well as emphasizing the need for pauses between phrases.

This short treatise represents a useful complement to the collections of Caesarius of Heisterbach and Conrad of Eberbach and the statute of the general chapter mentioned above. All these writings concern the fitting performance of the office, which is essential to the proper functioning of the monastic community envisioned by the Rule of Benedict, as Bernard of Clairvaux himself emphasized in one of his sermons on the Song of Songs:

According to our rule, nothing may be put before the work of God, the name by which father Benedict called the rites of praise that we render to God daily in the oratory, showing by this more clearly that he wished us to be intent upon that task. Therefore I admonish you, dearly beloved, always to take part purely and vigorously in divine praises. Vigorously, so that just as you stand reverently, so also you stand briskly in chanting the praises of God, not lazy, not sleepy, not yawning, not saving your voices, not cutting off half the words, not jumping over them entirely, not with broken and slack voices sounding something stammering through the nose in a womanly fashion, but drawing out the words of the Holy Spirit with manly sound and disposition, as is fitting.44

This passage was quoted in full by Conrad of Eberbach at the beginning of the chapter on the vain singer in the Exordium Magnum (5.20, cited above), endowing it with the authority of a proof text. Bernard’s own words on singing, and the notion that a particular form of chant performance constituted adherence to the Rule, pervade Cistercian writings on music. In the first half of the twelfth century the Cistercians reformed the chants of their antiphoner and hymnary in an attempt to restore what they considered authoritative versions of the chant so as to achieve an authentic observance of the Rule.45

The desire for a return to earlier traditions parallels the Cistercian renewal of the early monastic imaginary with its ever-present angels and demons. Giles Constable has situated Bernard of Clairvaux’s statements regarding chant performance in the context of the Cistercian revision of the chant and he has also pointed out their relationship to an exemplum, extant in three different versions of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, that recounts Bernard’s vision of angels who were present among the monks of Clairvaux during matins recording each singer’s degree of devotion in a different writing medium.46 According to the Collectaneum Exemplorum, words performed purely for the love of God were recorded in gold, those sung on account of the saints in silver, those said out of habit or the enjoyment of singing were written in ink, and those produced complainingly by unwilling singers were recorded in water. The angels were altogether unable to write down the words emitted negligently or with levity of the mind.47 The version in the Exordium Magnum states that the angels writing in gold signified the singers’ fervour of devotion to the service of God and concentration on the text being sung. Writing in silver indicated the singers’ lesser degree of passion, albeit still pure devotion. Writing in ink signalled the fact that they sang without much devotion but with good will, and writing in water expressed the defects of singers afflicted by somnolence or laziness or distracted by useless thoughts, whose hearts were not in concord with their voices. Those whose singing the angels did not record at all had developed a lamentable hardness of heart, had forgotten their profession and the fear of God.48 These anecdotes reflect both the singers’ varying degrees of participation and the belief in the presence of angels at the office, mentioned in the Rule of the Master and the Rule of Benedict.

An essential aspect of medieval monastic thought was the tenet that in the liturgy, heavenly and earthly singers were joined in common praise. This ideal appears in the eighth distinction of Caesarius of Heisterbach’s Dialogus Miraculorum, where he recounts a vision experienced in a monastery in Saxony during the performance of the Te Deum laudamus, a non-scriptural hymn sung at the end of matins on Sunday and feast days. A young girl (presumably an oblate or novice) who was allowed to attend matins only on high feast days was compelled by her tutor to leave before the conclusion of the service so as to retire to bed. Remaining near the choir so as to listen, she saw the singers taken up to heaven when the Te Deum began. As the performance progressed, at each reference in the text to apostles, prophets, and so on, the girl saw the corresponding group revealed on high; during the concluding phrase of the chant, the choir descended to earth and the heavens closed.49 This literal illustration of the text reflects the ideal joining of celestial and earthly choirs that was a common theme of medieval liturgical commentary.50 An earlier exemplum in the Cistercian Collectaneum Exemplorum recounts that some of those in the choir saw angels circulating among them during the singing of the Te Deum, rejoicing in the devotion of the singers. According to this brief text, the vision signifies that

one must take great care to sing with devotion <…> pausing briefly after each phrase and slightly lengthening both the words and the syllables (Unde magnopere curandum est ut cum deuotione cantetur <…> per clausas breuiter pausando et uoces et sillabas aliquantulum protrahendo).51

It is no coincidence that the language of the conclusion echoes twelfth-century Cistercian legislation on singing as well as the short treatise attributed to Bernard of Clairvaux: in this monastic tradition, a particular style and technique of singing had specific spiritual implications. It may be significant that the closely related narratives in the Exordium Magnum and Dialogus Miraculorum (both from the early thirteenth century) do not employ the technical language of chant performance, in contrast to the earlier Collectaneum Exemplorum, compiled a few decades after the completion of the Cistercian chant reform.52 All, however, reflect the ideal of angelic participation in the liturgy. The exempla concerning the involvement of angels in the Te Deum formed part of the same liturgical theology as those on demonic interference in the monastic office. All reinforced the fundamental concept that made the performance of the office such a central focus of Cistercian endeavours: the ancient and powerful belief that by singing together they forged a living link between the monastic community and the divine.

Endnotes

- For a useful account of the role of the grotesque in monastic visual culture, see T. E. A. Dale, ‘Monsters, corporeal deformities, and phantasms in the cloister of St-Michel-de-Cuxa’, Art Bulletin, lxxxiii (2001), 402–36.

- Matins on Sundays and feast days could begin as early as 2.30 a.m.

- My own experience suggests that singing the office in a darkened church has a powerful effect on the imagination, and that the acoustical properties of medieval stone churches would only intensify the visual and aural perceptions discussed here.

- For a recent discussion of matins as indicative of a particular monastery’s identity, see S. Boynton, Shaping a Monastic Identity: Liturgy and History at the Imperial Abbey of Farfa, 1000–1125 (Ithaca, N.Y., 2006).

- A general discussion of liturgical reform in the twelfth century can be found in C. Waddell, ‘The reform of the liturgy from a Renaissance perspective’, in Renaissance and Renewal in the Twelfth Century, ed. R. L. Benson and G. Constable (Cambridge, Mass., 1982), pp. 88–109.

- For a recent discussion of the central role of demonology in early monasticism, see D. Brakke, Demons and the Making of the Monk: Spiritual Combat in Early Christianity (Cambridge, Mass. and London, 2006).

- La Règle du Maître, ii, ed. and trans. A. de Vogüé (Sources chrétiennes, cvi, Paris, 1964), pp. 218–20: Non frequens tussis, non excreatus adsiduus, non anelus abundet, quia haec omnia orationibus et psalmis ad inpedimentum a diabolo ministrantur. Nam illud, quod superius diximus, et in orationibus caueatur, ut qui orat, si uoluerit, expuere aut narium spurcitias iactare, non inante sed post se retro proiciat propter angelos inante stantes, demonstrante propheta ac dicente: ‘In conspectu angelorum psallam tibi et adorabo ad templum sanctum tuum’. Ergo uides quia ante angelos ostendimur et orare et psallere. Nam ideo diximus breuem fieri orationem, ne per occasionem prolixae orationis obdormiat aut forte diu iacentibus diabolus eis ante oculos diuersa ingerat uel in corde aliud subministret.

- Regula Benedicti, ch. 19, in RB 1980: the Rule of St. Benedict in Latin and English with Notes, ed. T. Fry (Collegeville, Minn., 1980) (hereafter RB 1980), pp. 214–16: Ubique credimus divinam esse praesentiam et oculos Domini in omni loco speculari bonos et malos, maxime tamen hoc sine aliqua dubitatione credamus cum ad opus divinum assistimus. Ideo semper memores simus quod ait propheta: ‘Servite Domino in timore’, et iterum: ‘Psallite sapienter, et: In conspectu angelorum psallam tibi’. Ergo consideremus qualiter oporteat in conspectu divinitatis et angelorum eius esse, et sic stemus ad psallendum ut mens nostra concordet voci nostrae.

- G. Constable, ‘The concern for sincerity and understanding in liturgical prayer, especially in the twelfth century’, in Classica et Mediaevalia: Studies in Honor of Joseph Szövérffy, ed. I. Caslef and H. Buschhausen (Washington and Leiden, 1986), pp. 17–30, at p. 19.

- Regula Benedicti, ch. 58; (RB 1980, p. 270): Illa autem vestimenta quibus exutus est reponantur in vestiario conservanda, ut si aliquando suadenti diabolo consenserit ut egrediatur de monasterio – quod absit – tunc exutus rebus monasterii proiciatur.

- Les Apopthegmes des Pères: Collection systematique, 18.48.1–27, ed. and trans. J.-C. Guy (Sources chrétiennes, cdxcviii, Paris, 2005), pp. 112–15.

- On monastic texts presenting the Devil and demons as ever-present, see E. Langton, Supernatural: the Doctrine of Spirits, Angels, and Demons, from the Middle Ages until the Present Time (1934), pp. 160–74.

- R. Colliot, ‘Rencontres du moine Raoul Glaber avec le diable d’après ses Histoires’, in Le Diable au Moyen Age: Doctrines, problèmes moraux, représentations (Sénéfiance vi, Aix-en-Provence and Paris, 1979), pp. 117–32.

- Rodulfi Glabri Historiarum Libri Quinque, ed. J. France (Oxford, 1989), p. 216.

- Rodulfi Glabri Historiarum Libri Quinque, p. 218: Nam dum aliquando in beati martyris Leodegarii monasterio, quod Capellis cognominatur, positus degrem, nocte quadam, ante matutinalem sinaxim, adstitit mihi ex parte pedum lectuli forma homunculi teterrimae speciei. Erat enim, quantum a me dignosci potuit, statura mediocris, collo gracili, facie macilenta, occulis nigerrimis, front rugosa et contracta, depressis naribus, os exporrectum, labellis tumentibus, mento subtracto ac perangusto, barba caprina, aureas irtas et praeacutas, capillis stantibus et incompositis, dentibus caninis, occipitio acuto, pectore tumido, dorso gibat, clunibus agitantibus, uestibus sordidis, conatus aestuans, ac toto corpore preceps; arripiensque summitatem strati in quo cubabam, totum terribiliter concussit lectulum, ac deinde infit: ‘Non tu in hoc loco ultra manebis’. At ego territus euigilansque, sicuti repente fieri contingit, aspexi talem quem prescripsi. Ipse uero infrendens idemtidem aiebat: ‘Non hic ultra manebis’. Ilico denique a lectulo exiliens cucurri in monasterium, atque ante altare sanctissimi patris Benedicti prostratus ac nimium pauefactus diutine decubui, cepique acerrime ad memoriam reducere quicquid ab ineunte aetate offensionum grauiumque peccaminum procaciter seu neglegenter commiseram.

- Rodulfi Glabri Historiarum Libri Quinque, p. 220: Post haec igitur, in monasterio sancti Benigni Diuionensis martyris locatus, non dispar, immo isdem mihi uisus est in dormitorio fratrum. Incipiente aurora diei, currens exiit a domo latrinarum taliter inclamanda: ‘Meus bacallaris ubi est? meus bacallaris ubi est?’ Sequenti quoque die, eadem fere hora, aufugiens abiit exinde quidam frater iuuenis, mente leuissimus, Theodericus nomine, reiecto habitu per aliquod temporis spacium seculariter uixit. Qui postmodum corde conpunctus ad propositum sacri ordinis rediit.

- Rodulfi Glabri Historiarum Libri Quinque, pp. 220–2: Tercio quoque, cum apud cenobium beatae semperque uirginis Mariae, cognomento Meleredense, demorare, una noctium dum matutinorum pulsaretur signum et ego labore quodam fessus, non, ut debueram, mox ut auditum fuerat exsurrexissem, mecumque aliqui remansissent, quos uidelicet praua consuetudo illexerat, ceteris ad ecclesiam concurrentibus, egrediens autem post fratrum uestigia hanelus ascendit gradum presignatus demon, ad dorsum manibus reductis, herensque parieti bis terque repetabat dicens: ‘Ego sum, ego sum, qui sto cum illis qui remanent’. Qua uoce excitus caput eleuans, uidi recognoscens quem bis dudum iam uideram. Post diem uero tertium unus ex illis fratribus qui, ut dicimus, clancule cubitare soliti fuerant, procaciter a monasterio egressus, praefato demone instigante, sex dies extra monasterium cum secularibus tumultuose mansit. Septima tamen die correptus recipitur.

- Two instances of this idea appear in an anonymous gloss on a hymn for matins in three manuscripts from eleventh-century northern France (Amiens, Bibliothèque Louis Aragon (formerly Bibliothèque Municipale) 131 and Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, MS. lat. 103 and 11550): Qui ad celebrandum diuinum officium uel obsequium festinat, necesse est ut a se omnem somnolentiam et torporem repellat. Aliter dominum quem querit, inuenire non poterit; Isidore of Seville’s Regula monachorum, iii. 59–61, in San Leandro, San Isidoro, San Fructuoso. Reglas monásticas de la España visigoda, ed. J. Campos Ruiz and I. Roca Melia (Madrid, 1971), p. 93: Torporem somni atque pigritiam fugiat, vigiliisque et orationibus sine intermissione intendat.

- Wiesbaden, Hessische Landesbibliothek, MS. 2 fo. 479r: Vide quid illud sit quo es induta filia saluationis et esto stabilis et numquam cades; O nescio quid faciam aut ubi fugiam oue michi non possum perficere hoc quod sum induta certe illud uolo abicere.

- Wiesbaden, Hessische Landesbibliothek, MS. 2 fos. 480v–481r: O fugitiue, ueni, ueni ad nos, et deus suscipiet te; O anima fugitiua, esto robusta et indue te arma lucis.

- On the letter, see also W. Flynn, ‘“The soul is symphonic”: meditation on Luke 15:25 and Hildegard of Bingen’s letter 23’, in Music and Theology: Essays in Honor of Robin A. Leaver, ed. D. Zager (Lanham, Md., 2007), pp. 1–8.

- Hildegardis Bingenis Epistolarium, ed. L. van Acker (Corpus Christianorum: Continuatio Mediaeualis, xci, Turnhout, 1991), p. 64: Cum autem deceptor eius, diabolus, audisset quod homo ex inspiratione Dei cantare cepisset, et per hoc ad recolendam suauitatem canticorum celestis patrie mutaretur, machinamenta calliditatis sue in irritum ire uidens, ita exterritus est, ut non minimum inde torqueretur, et multifariis nequitie sue commentis semper deinceps excogitare et exquirere satagit, ut non solum de corde hominis per malas suggestiones et immundas cogitationes seu diuersas occupationes, sed etiam de ore Ecclesie, ubicumque potest, per dissensiones et scandala uel iniustas depressiones, confessionem et pulchritudinem atque dulcedinem diuine laudis et spiritalium hymnorum perturbare uel auferre non desistit.

- On the role of the Ordo Virtutum in Hildegard’s monastic community, see M. Fassler, ‘Composer and dramatist: “Melodious singing and the freshness of remorse”’, in Voice of the Living Light: Hildegard of Bingen and her World, ed.B. Newman (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1998), pp. 168–75.

- Petri Cluniacensis Abbatis De Miraculis Libri Duo, 1.17, ed. D. Bouthillier (Corpus Christianorum: Continuatio Mediaeualis, lxxxiii, Turnhout, 1987), pp. 53–4.

- For a useful discussion of the current state of research on Cistercian exemplum literature, see B. P. McGuire, ‘Cistercian storytelling – a living tradition: surprises in the world of research’, Cistercian Studies Quarterly, xxxix (2004), 281–309.

- B. P. McGuire, ‘Friends and tales in the cloister: oral sources in Caesarius of Heisterbach’s Dialogus Miraculorum’, Analecta Cisterciensia, xxxvi (1980), 167–247, at p. 172.

- For analysis of the Dialogus Miraculorum and its sources, the fundamental studies remain McGuire, ‘Friends and tales in the cloister’; B. P. McGuire, ‘Written sources and Cistercian inspiration in Caesarius of Heisterbach’, Analecta Cisterciensia, xxxv (1979), 227–82.

- Collectaneum Exemplorum et Visionum Clarevallense, 3.14, ed. O. Legendre (Corpus Christianorum: Continuatio Mediaeualis, ccviii, Turnhout, 2005), pp. 256–7.

- Collectaneum Exemplorum, 4.30, ed. Legendre, pp. 303–4. I am grateful to Martha Newman for referring me to this exemplum.

- Conrad of Eberbach, Exordium Magnum Cisterciense sive Narratio de Initio Cisterciensis Ordinis, 5.18, ed. B. Griesser (Corpus Christianorum: Continuatio Mediaeualis, cxxxviii, Turnhout, 1994), pp. 375–7.

- Elizabeth Teviotdale very kindly pointed out to me a thirteenth-century Cistercian historiated initial depicting, in its upper register, the celebration of mass and, in the lower register, a group of monks singing from a choirbook inscribed with the text Cantate fortiter. This image, which would seem to attach a positive value to singing loudly, is suggestive in the context of exempla that mention loud singers. For a reproduction of the miniature with commentary, see Buchmalerei der Zisterzienser: kulturelle Schätze aus sechs Jahrhunderten, Katalog zur Ausstellung ‘Libri Cistersienses’ im Ordensmuseum Abtei Kamp, Nordrhein-Westfalen (Stuttgart, 1998), pp. 136–40 (I owe this reference to Elizabeth Teviotdale). Cistercian exempla concerning the mass are not discussed in the present study because they do not fit into the same distinctive pattern of demonic intervention seen in narratives about the Divine Office.

- Caesarius of Heisterbach, Dialogus Miraculorum, 5.9, ed. J. Strange (Cologne, 1851), i. 181: Tempore quodam clericis quibusdam in ecclesia quadam saeculari fortiter, id est, clamose, non devote, cantantibus, et voces tumultuosas in sublime tollentibus, vidit homo quidam religiosus, qui forte tunc affuit, quendam daemonem in loco eminentiori stantem, saccum magnum et longum in sinistra manu tenere, qui cantantium voces dextera latius extensa capiebat, atque in eundem saccum mittebat. Illis exploeto cantu inter se gloriantibus, tanquam qui bene et fortiter Deum laudassent, respondit ille, qui viderat visionem: Bene quidem cantastis, sed saccum plenum cantastis.

- Dialogus Miraculorum: Quantum ei devota placeat vocum exaltatio, satis audies in sequenti distinctione capitulo quinto. Ibidem invenies, quantum ex hoc daemones laetentur, si sine humilitate in psalmodia voces exaltentur.

- Aelred of Rievaulx, De Speculo Caritatis, 2.23, ed. C. H. Talbot, in Aelredi Rievallensis Opera Omnia, ed. A. Hoste and C. H. Talbot (Corpus Christianorum: Continuatio Mediaeualis, i, Turnhout, 1971), pp. 97–9. Another twelfth-century text denouncing ostentatious, ‘womanly’ singing in church is John of Salisbury’s Policraticus (written in 1159) (see Policraticus, 1.6, ed. K. S. B. Keats-Rohan (Corpus Christianorum: Continuatio Mediaeualis, cxviii, Turnhout, 1993), p. 46).

- On the distinctio on demons as a treatise on demonology, see S. M. Barillari, Cesario di Heisterbach, Sui demòni (Alessandria, 1999), pp. 13–20. For a broader study of demons in the Dialogus Miraculorum, see S. M. Barillari, ‘Dèmoni e demòni. Per una definizione della figura diabolica negli exempla di Cesario di Heisterbach’, Lingua e letteratura, xviii (1992), pp. 73–82; and S. M. Barillari, ‘“Per gratiam Christi et ministerium diaboli”. Rappresentazioni e funzioni del demoniaco negli exempla di Cesario di Heisterbach’, L’immagine riflessa, new ser., ii (1993), 39–68.

- On the Cistercian understanding of this vision as a spiritual gift, see T. License, ‘The gift of seeing demons in early Cistercian spirituality’, Cistercian Studies Quarterly, xxxix (2004), 49–65 (specific reference to Herman at p. 53).

- Caesarius of Heisterbach, Dialogus Miraculorum, 5.5, ed. Strange, pp. 281–2.

- Dialogus Miraculorum, 5.5, ed. Strange, pp. 282–3: Alio itidem tempore, in vigilia, ut puto, Sancti Columbani, tunc eo exsistente Priore, cum chorus Abbatis incipere primum matutinarum Psalmum, scilicet ‘Domine quid multiplicati sunt qui tribulant me?’ daemones in choro adeo multiplicati sunt, ut ex illorum concursu et discursu mox in eodem psalmo fratres fallerentur. Quos cum chorus oppositus conaretur corrigere, daemones transvolaverunt et se illis miscentes ita eos turbaverunt, ut prorsus nescirent quid psallerent. Clamavit chorus contra chorum. Dominus Abbas Eustachius, et Prior Hermannus, qui haec vidit, a stallis suis semoti, cum stis ad hoc conarentur, non poterant illos ad viam psalmodiae reducere, neque vocum dissonantias unire. Tandem Psalmo illo modico et valde usitato, cum labore pariter atque confusione qualicunque modo expleto, diabolus, totius confusionis caput, cum suis satellitibus abcessit, et pax turbata psallentibus accessit.

- Dialogus Miraculorum, 5.5, ed. Strange, pp. 283–4: Cum nocte quadam hebdomadarius invitatorii antiphonam incipiere, et monachus ei proximus voce mediocri psalmum intonaret, Herwicus, tunc subprior, cum ceteris sernioribus eadem voce qua ille inceperat, psallere coepit. Stabat iuvenis quidam minus sapiens in inferiori pene parte chori, qui indigne ferens psalmum tam submisse inceptum, fere quinque tonis illum exaltavit. Subpriore ei resistente, ille cedere contemsit, et cum multa pertinacia ei resistente, ille cedere contemsit, et cum multa pertinacia victoriam obtinuit. Cuius partes in proximo versiculo quidam ex oppositio choro adiuverunt. Propter scandalum et dissonantiae vitium ceteri cesserunt. Mox is, qui supra, vidit daemonem de monacho sic triumphante quasi candens ferrum prosilientem et in oppositum chorum in eos, qui eius partem roboraverant, se transferentem. Ex quo colligitur, quod magis Deo placeat humilis cantus cum cordis devotione, quam voces etiam in coelum arroganter exaltatae.

- Viros decet virili voce cantare, et non more femineo tinnulis vel, ut vulgo dicitur, falsis vocibus histrionicam imitari lascivam. Et ideo constituimus mediocritatem servari in cantu, ut et gravitatem redoleat et devotio conservetur (‘Instituta generalis capituli apud Cistercium’, in Narrative and Legislative Texts from Early Cîteaux, ed. C. Waddell (Cîteaux, 1999), pp. 360, 489–90).

- Exordium Magnum, 5.20, ed. Griesser, p. 382: …ut uersum responsorii sui non plane in grauibus, sed in acutis uel potius in acutissimis uocem quatiendo tinnulos que modulos flexibilitate uocis formando solita lasciuia decantaret.

- Exordium Magnum, 5.20, ed. Griesser, p. 382: Ideoque summopere nitendum est quatenus secundum mediocritatem, quam nobis sanctus ordo noster praescribit, necnon et secundum auctoritatem, qua regula, quam professi sumus, nos instruit et singuli specialiter et omnes in commune pariter cum grauitate, cum timore et tremore atque cum humilitate psallamus et cantemus Deo nostro.

- C. Waddell, ‘A plea for the Institutio Sancti Bernardi Quomodo Cantare et Psallere Debeamus’, in Saint Bernard of Clairvaux: Studies Commemorating the Eighth Centenary of his Canonization, ed. M. B. Pennington (Kalamazoo, Mich., 1977), p. 187: Venerabilis pater noster beatus Bernardus abbatis clareuallis precepit monachis hanc formam canendi tenere, affirmans hoc deo et angelis placere, ita dicens: Psalmodiam non nimium protrahamus, sed rotonde et uiuia uoce cantemus. Metrum et finem uersus simul intonemus et simul dimittamus. Punctum nullus teneat, sed cito dimittat. Post metrum bonam pausam faciamus. Nullus ante alios incipire et nimis currere presumat, aut post alios nimium trahere uel punctum tenere. Simul cantemus, simul pausemus, semper auscultando.

- Bernard of Clairvaux, Sermon 47 on the Song of Songs, Patrologia Latina, ed. J. P. Migne (221 vols., Paris, 1844–1903), clxxxiii, col. 1011C: Ex regula namque nostra nihil operi Dei praeponere licet. Quo quidem nomine laudum solemnia, quae Deo in oratorio quotidie persolvuntur, pater Benedictus ideo voluit apellari, ut ex hoc clarius aperiret quam nos operi illi vellet esse intentos. Unde vos moneo, dilectissimi, pure semper ac strenue divinis interesse laudibus. Strenue quidem, ut sicut reverenter, ita et alacriter Domino assistatis: non pigri, non somnolenti, non oscitantes, non parcentes vocibus, non praecidentes verba dimidia, non integra transilientes, non fractis et remissis vocibus muliebre quiddam balba de nare sonantes; sed virili, ut dignum est, et sonitu, et affectu voces sancti spiritus depromentes.

- The literature on the Cistercian chant reform is too extensive to be addressed in full here. A particularly useful exposition can be found in C. Waddell, ‘The origin and early evolution of the Cistercian antiphonary: reflections on two Cistercian chant reforms’, in The Cistercian Spirit. A Symposium: in Memory of Thomas Merton, ed. M. B. Pennington (Cistercian Studies, iii, 1970), pp. 190–223. Recent discussions of the exemplars used for the revision of the chant are M. P. Ferreira, ‘La réforme cistercienne du chant liturgique revisitée’, Revue de musicologie, lxxxix (2003), 47–56; introduction to The Primitive Cistercian Breviary (Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Ms. Lat. Oct. 402), with Variants from the ‘Bernardine’ Cistercian Breviary, ed. C. Waddell (Spicilegium Friburgense, xliv, Fribourg, 2007). Treatises on the revision of the chant repertory are ‘Epistola S. Bernardi de revisione cantus Cisterciensis’, and ‘Tractatus Cantum quem Cisterciensis Ordinis ecclesiae cantare consueverant’, both ed. F. J. Guentner (Corpus scriptorum de musica, xxiv, Rome, 1974), pp. 21–41; and the ‘Regule de arte musica’, ed. most recently in C. Maître, La réforme cistercienne du plain-chant: étude d’un traité théorique (Brecht, 1995). On the revision of the Cistercian hymn repertory, see the introduction to The Twelfth-Century Cistercian Hymnal, ed. C. Waddell (Trappist, Ky., 1984), i. 3–22.

- Constable, ‘The concern for sincerity and understanding’, p. 24.

- Collectaneum Exemplorum, 4.7, ed. Legendre, pp. 264–5.

- Exordium Magnum, 2.3, ed. Griesser, p. 75.

- Dialogus Miraculorum, 8.90, ed. Strange, ii, pp. 157–8.

- See G. Iversen, Chanter avec les anges. Poésie dans la messe mediévale. Interprétations et commentaires (Paris, 2001). For a recent study showing the realization of this idea in musical practice, see L. Kruckenberg, ‘Neumatizing the sequence: special performances of sequences in the central middle ages’, Journal of the American Musicological Society, lix (2006), 243–317.

- Collectaneum Exemplorum, 3.15, ed. Legendre, pp. 257–8. The ellipsis reflects the erasure of eight letters in the manuscript.

- Exordium Magnum, 2.4, ed. Griesser, p. 76.

Contribution (87-104) from European Religious Cultures: Essays Offered to Christopher Brooke on the Occasion of His Eightieth Birthday, edited by Miri Rubin (University of London, 08.05.2020), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.