Neither of these regions allow for any simple categorization of Roman versus non-Roman.

By Dr. Daniel Hoyer

Project Manager, Seshat Database of Social Evolution

Evolution Institute

University of Oxford

Introduction

The organizers of the conference1 from which the papers in this volume were drawn, ‘Rome and the Worlds Beyond Roman Frontiers,’ asked participants to focus on the interaction between people within Rome’s borders, or the Roman world generally, and those outside of it. The papers included in this volume attest to the significance of this topic. There is, however, an inherent problem with the way the topic is framed; it is not always clear what groups of people we should consider as ‘insiders’ to the Roman world and what groups ‘ outsiders,’ and how to interpret changes in the status of a particular group. Is this meant in terms of political integration? Military turmoil? Social or cultural unity? This issue is especially acute for the mid-third century AD, a tumultuous and still poorly understood time when the Roman Empire experienced nearly constant warfare against both civil and foreign enemies, devastating plagues, a long series of claimants to the imperial throne, as well as many instances of political, military, and economic dislocations. These dislocations belie a simple picture of a Roman world versus groups of non-Roman others or ‘outsiders,’ as the civil warfare and the great number of different claimants to the supreme power who came forward during this period challenged the allegiances of Roman citizens, calling into question what it meant to be ‘inside’ or ‘outside’ the Empire.

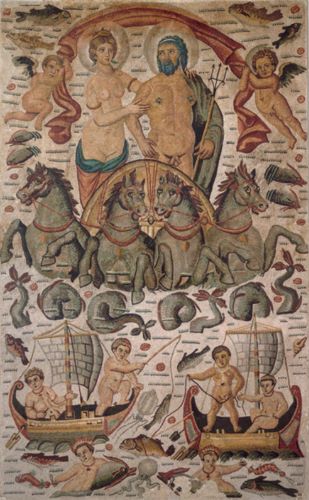

In one case, that of northwestern Europe in the AD 260s, the problems of the period led to the rise of the Gallic emperor Postumus, a successful military leader who exercised authority over a large tract of territory that had once been an integral part of the previously united Roman Empire. During Postumus’ rule, Rome was truly a fractured state, with Europe turned into a battleground between the legitimate, ‘insider’ emperor and senate at Rome and the breakaway, ‘outsider’ Empire ruled by Postumus, defining ‘outsider’ in terms of political integration. Yet, in many ways Postumus’ reign did not encompass a complete break from the traditions and institutions of imperial Roman life and in several important respects the Gallic Empire continued to function as a typical Roman region; an ‘insider’ regime, at least from a social, cultural, and ideological sense. Other regions of the western Roman Empire, contrarily, experienced the period very differently from Gaul. For instance, the Roman holdings in North Africa were never truly politically ‘outside’ of the central imperial authority in the way that parts of northwestern Europe were under Postumus. Roman Africa likewise remained a socially, culturally, and ideologically ‘insider’ area throughout this time. Yet, the region was certainly affected by the period’s many troubles and did experience dislocations of traditional rule in certain areas; in terms of civil warfare and the rise of non- traditional authority figures, North Africa was as ‘outside’ as any other region in the western Empire.

The main point to take away from this is that neither of these regions allow for any simple categorization of Roman versus non-Roman, of ‘outsider’ versus ‘insider;’ both areas experienced military turmoil and political dislocation and both retained certain important traditional Roman institutions. The histories of these different parts of the western Empire during the mid-third century are, however, quite distinct. Since these differences cannot be explained merely by appeal to political and military fracturing, or the ‘outsideness’ of one region compared to the other, another approach must be sought.

In this article, then, I explore the problem of Roman cohesiveness during the mid-third century AD by looking at how these two very different regions were affected by the problems of the period. By taking a long view of the period, stretching back into the late second century AD, and by comparing the regions along several key factors, namely political, ideological, military, economic, and financial,2 it becomes clear that the two areas emerged from the late Antonine and Severan periods following very different paths. After a brief summary of the current state of scholarship on the history of the third century AD, I then proceed to give an account of how each of the factors noted above developed over the course of the imperial period and how this affected the two regions under investigation here. In each of the following sections, I discuss first the interesting case of Postumus, then jump back in time to discuss the events of AD 238, pointing out the similarities and differences with the experience of Postumus’ Imperium Galliarum. The cases are presented out of chronological order, since Postumus’ experience represents perhaps the pinnacle of the third century turmoil and presents a relatively clear account of the complex negotiation of political, social, and economic power in which Roman rulers were forced to engage during this period. Treating the events that transpired in Africa in AD 238 second offers a sharper contrast, and allows for a more forceful argument about the key differences between the two cases.

The main thrust of this article is to make an explicit comparison between Gaul and Africa in order to illustrate clearly the importance of these key factors on the regions’ divergent experiences during one of the most momentous and turbulent periods in the history of the Roman Empire. I conclude with the observation that analyzing these historical events in terms of where groups of people stand in relation to the Roman world, whether they ought to be treated as ‘outsiders’ or ‘insiders,’ fails to do proper justice to the true complexity of the situation. I argue that, rather, it is important to understand the long-term structural developments, which affected particular historical outcomes and to recognize that different facets of a society can progress along different paths, meaning that these regions at once existed both ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ of the traditional structures of the Roman Empire.

The Third Century ‘Crisis’

The notion that the third century AD was a time of crisis, when the stability and prosperity of the High Roman Empire were suddenly undermined by barbarian invasions, disease, civil warfare, and financial ruin, has long featured prominently in analyses of the later Roman Empire.3 This crisis has traditionally been seen as an all-encompassing decline in Roman civilization which began at the end of the Severan dynasty in AD 235 and which ultimately led, with perhaps a brief recovery in the early fourth century, to the collapse of the Roman state and the onset of the Medieval period.4 In more recent years, how-ever, the idea that there was a crisis at all has been questioned. Some scholars have gone so far as to suggest that crisis is an inadequate description of this period, preferring terms like transformation and change.5 Others, notably Witschel, argue that there was no single, Empire-wide crisis, rather a series of isolated and regionally specific problems, such as disease in the Eastern Mediterranean and military threats along the northern frontiers, while other areas actually experienced a period of prosperity.6 Le Glay, similarly, contends that the events of the third century need to be considered not only with an eye to regional differences, but also along separate lines of inquiry; political stability, the military situation, changing social structures, economic activity, etc.7

Although there is still no consensus on how to describe the period, it is undeniable that in at least some parts of the Roman world, certain fundamental changes were occurring during this time. One of the clearest and most damaging changes during the mid-third century was the rise of the so-called Soldatenkaiser;8 popular and successful Roman military leaders who aspired to rule the Roman world and who used their control of groups of soldiers to claim, often only briefly, the ultimate power in Rome. The prevalence of these soldier-emperors, who held the reigns of power essentially from the death of Severus Alexander in AD 235 until Aurelian’s reunification of the Empire thirty-nine years later, had serious consequences on Rome’s political and military fabric. The constant series of usurpers and claimants to the seat of power in Rome challenged, or at least problematized, the way in which the entire Empire was ruled, leading to outright civil warfare and political fragmentation. Yet, although such troubles were certainly felt Empire-wide, the fragmentation of central Roman authority must also be explored with an eye towards regional differences. Specifically, as I argue in this paper, regional differences in three of the key elements of Roman life—military activity, economic productivity, and financial stability—caused the regions of the western Empire to react differ-ently to the political and ideological problems afflicting Rome during this time.

The most fruitful avenue to test this hypothesis and to illuminate the exact impact that each of the above-mentioned factors had on the Roman world is through direct comparison between different regions. I offer in this paper, then, a brief look at two important episodes of the third century AD: the so-called ‘Gallic Empire’ of Postumus and his successors, lasting from AD 260 to 274, and the events of the year AD 238 in North Africa which saw the ascension to the throne of Gordian I as well as the short-lived revolt of Capellianus, praetorian legate of Numidia. These moments of instability in the two regions were simi-lar in several respects. They both involved political and military upheaval as well as civil fighting instigated by popular local leaders, and both regions also saw some continuity in certain important institutions such as with the maintenance of the symbols of authority and of administrative offices. Yet, in spite of having similar beginnings, the effects of these political and military upheavals in Gaul were significantly more intense and long lasting than those in Africa.

In other words, both regions suffered from the problems of the period and both regions were able to maintain continuity in certain aspects of Roman life, although Gaul experienced a political, military, and economic break from the rest of the Empire in ways that Africa never did. The crucial question, then, is what caused this difference? This is the question I explore in depth in the remainder of the article, highlighting the political, ideological, military, economic, and financial elements as some of the essential factors in how the two episodes unfolded over the course of the third century AD. In answering this question, I posit that the disruptions which ultimately led to the rise of the Gallic Empire as well as Africa’s remarkable stability during the period both had deep, long-term structural roots. Moreover, I contend that the complexity and diversity of the regions’ experiences during this time belie any simple categorization of either case as being ‘outside’ or ‘inside’ the Roman Empire.

Political Upheaval, Civil Warfare, and Ruling Ideology

Before exploring the different factors that shaped the way the different regions reacted to this period of turmoil, it is necessary to provide an overview of the actions and events that occurred in northwestern Europe in the AD 260s along with those from Africa in AD 238, focusing on how the stability of Roman political life was disrupted in the different regions. First, a look at the period from roughly AD 260 to AD 274 when much of Rome’s territory in northwestern Europe fell under the authority of Marcus Cassianius Latinius Postumus.

The precise timeline of events is still debated, but, simply put, in AD 258 Postumus, as governor of Lower Germany, participated in the defeat of an invading Barbarian tribe, the Iuthungi, led by the emperor Valerian’s son Gallienus. According to Zosimus,9 Postumus was very generous rewarding his soldiers with booty after the victory, but the Praetorian Prefect, a certain Silvanus, took much of this booty away. The troops then revolted, besieged and captured Cologne, killed Silvanus and hailed Postumus emperor.10 Postumus quickly consolidated his power, taking control of all the armies in Gaul and Germany and, by AD 261, extending his authority into parts of Spain as well as Britain.11 The area under his rule, termed the Imperium Galliarum, was thus comprised of what had been several of Rome’s provinces in northern Europe, eleven at the height of the Empire.12 The security of the Gallic Empire as an entity distinct from the central Roman state was not, however, entirely unchallenged. Postumus was forced to repel a major attack led by Gallienus, the central Roman emperor, in an attempt to reclaim the Gallic territory for Rome in AD 265.13 Then in AD 269, after Postumus was murdered by his own troops, the next central Roman emperor, Claudius II Gothicus, was able to wrest Postumus’ Spanish holdings away from the Gallic Empire. Claudius, however, was unable to capitalize on his victory or on Gaul’s internal turmoil at the time and the Imperium Galliarum remained largely intact under the Gallic emperors Marius, Victorianus, and the two Tetrici.14 The Imperium Galliarum, thus, existed in effect as an independent entity separate from, or ‘outside’ of, the central Roman state until the defeat of Tetricus I and II, the last of the Gallic emperors, by Aurelian in AD 274.15

This episode at first glance appears rather unremarkable in the context of the western Empire during the third century AD: a successful and popular military leader is hailed emperor by his troops after a successful campaign against foreign enemies, leading to some regional civil fighting. By this reading, Postumus was simply one in a line of so-called Soldatenkaiser; perhaps more successful than most others, but functioning in the same way as other usurpers of the period such as Maximinus, Decius, Aemilianus, and Hostilian, generals who briefly rose to power during the mid-third century and who had to constantly fight against other claimants to the throne.16 Yet, in certain ways Postumus does not belong with the other imperial claimants of the period. As Eck recently remarked, Postumus’ usurpation of power was much more durable than others’, his rule circumscribed the authority of the central Roman state to a greater degree, and he was able to establish a dynastic succession, albeit short-lived, which almost no other usurper could do.17 There is a reason, after all, that most modern scholars term Postumus the emperor of his own territory, the Imperium Galliarum, a distinction not bestowed on the other usurper-emperors.

There has, however, been a great deal of scholarly debate about the Gallic Empire, particularly concerning the exact timeline of events, the motivations behind Postumus’ actions, and the precise nature of his rule.18 Much of the controversy has surrounded the issue of whether Postumus was always content to rule over a circumscribed territory in the northwest part of the Empire, or whether he or his successors intend to invade Italy and rule over a unified Empire but were, for various reasons, simply prevented from doing so.19 This question of intent seems to me not only impossible to recover from the available sources, but largely to miss the point. Whatever Postumus or any of the other Gallic emperors wanted to do, the historical fact remains that their authority was exercised over a limited, circumscribed area carved out of the formerly unified Roman Empire. The important questions to be asked, then, are through what mechanisms Postumus consolidated his rule and, relatedly, to what extent was the Imperium Galliarum separate from, or ‘outside’ of, the rest of the Roman world?

In terms of trying to determine the nature of Postumus’ rule, it is, as has often been pointed out, very difficult to recover the exact nature and history of the Gallic Empire from the available sources. As far as can be reconstructed, however, it seems fairly clear that Postumus’ authority was based on his control of the many Roman soldiers who had been situated in the northwestern part of the Empire from the late second century AD, when the Empire’s German borders fell under serious threat. There were also many wealthy senatorial families living in Gaul at the time, and Postumus seems to have relied heavily on their wealth and power to fund and legitimate his rule.20 Another key aspect of Postumus’ policy was that he maintained several of the ideological and political traditions of previous Roman emperors.21 This is demonstrated clearly by some of the material evidence that has survived from his rule.

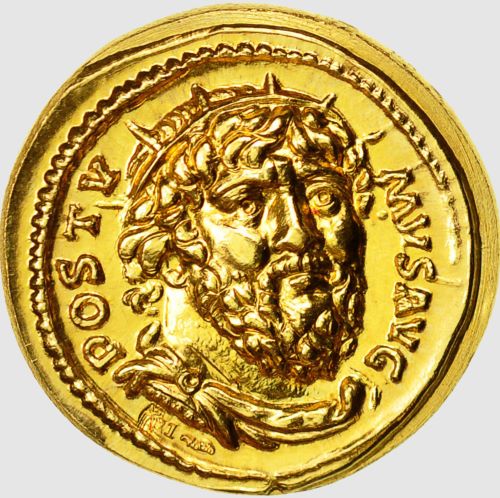

Firstly, in inscriptions Postumus was addressed using the normal imperial titulature, being hailed as Imperator Caesar Marcus Cassianius Latinius Postumus Pius Felix Invictus Augustus Germanicus.22 Similarly, on coins, which are probably the best evidence we possess concerning the Gallic Empire, Postumus is labeled on the obverse as Imp(erator) C(aesar), immediately identifying him as a typical, traditional Roman emperor. Likewise, on the reverses of these coins, Postumus is termed variously as Rest(itutor) Orbis (Restorer of the world), Pacator Orbis (Pacifier of the Globe), and Uberitas Aug(usti) (Wealthy/Fortunate emperor),23 placing Postumus in the traditional role of a caring and helpful emperor, ensuring the unity of the whole world and maintaining the wealth and prosperity of his subjects, the Roman people. Moreover, it is clear from both the epigraphic and numismatic evidence that Postumus and his successors retained many of the offices typical of Roman imperial administration, including consuls, governors, tribunes, pontifices, censors, and legates, and even continued to use consular dating on inscriptions.24

Further, just as Postumus is hailed in inscriptions using the traditional imperial titulature, these same inscriptions make it clear that he was imperator of something not quite the same as the old Roman Empire. An inscription found in Augsburg in Germany dating to AD 260, for instance, records a dedication by an elite Roman of equestrian rank, a vir perfectissimus named Marcus Simplicinius Genialis, recording the year with the formula “Imp(eratore) d(omino) n(ostro) [Postumo Au]g(usto) et [Honoratiano consulibus] (when our lord, the emperor Postumus Augustus, and Honoratianus were consuls).”25 This inscription illustrates that, regardless of whether or not Postumus intended to eventually rule over the entire territory that had once belonged to the Roman Empire, there is no doubt that the ‘our’ in Marcus Simplicinius’ dedication referred exclusively to the people in those parts of Europe where Postumus was recognized as the emperor. Crucially, this excluded those who still regarded Gallienus the true, legitimate Roman ruler.

Similarly, although some of the legends on the reverses of Postumus’ coins seek to identify him as a traditional Roman ruler, other types present the opposite message. He is referred to on certain coin issues as Salus Provinciarum (Savior of the Provinces) and Rest(itutor) Galliar(um) (Restorer of the Gallic [territory]), among other commemorations. The different reverse types featured on the Gallic coinage thus highlight Postumus’ unique dual role as both typical Roman emperor who unites the whole world and ensures wealth and prosperity for his subjects, but also as the chief authority responsible for the safety and cohesion of the specific provinces under his control, namely the Imperium Galliarum. The implied counterpoint to Postumus as defender of the Gallic territory, of course, are those from whom the Imperium Galliarum needed protecting, not only the hostile Barbarian tribes across the Danube but also his enemy the ‘legitimate’ Roman emperor Gallienus who tried, unsuccessfully, to remove Postumus from what he surely considered to be his legiti-mate seat of power.

Admittedly, what I offer above is a fairly idealistic view of the creation and impact of the iconography on imperial Roman coins. It needs to be pointed out that there is great scholarly debate over the precise nature of the images which appeared on Roman coins, centered around the issues of what authorities were responsible for choosing the images and text as well as how much ordinary users of the coins actually attended to, or were impacted by, the messages.26 This is not the proper place for a lengthy recapitulation of the arguments concerning the impact of coin iconography except to note that most scholars now agree that the images on Roman coins expressed the ideals and aims of the ruling authorities under whose name the coins were being produced, regardless of the level of direct control ruler’s asserted in creating the images.27 The extent to which coin users paid attention to the images and text on these objects and, thus, the impact which the coins’ iconographic messages had is impossible to determine. Let it suffice for the purposes of this article to con-clude that the images and text on coins produced by the Postumus as well as the central Roman emperors during the third century were consistent with the persona these rulers wished to present to their subjects.

Accepting the evidence from coin iconography and combining it with the epigraphic material, it is clear that Postumus was not trying to reject entirely Roman political and ideological norms and establish a completely different manner of rule in his new breakaway territory. This is, indeed, the main rea-son why many scholars have argued that Postumus intended to march on Rome and rule over a united Roman Empire just as all other claimants, but was prevented from it by certain unknown causes, such as internal issues or simply the power of the central Roman army.28 Yet, as mentioned, Postumus’ rule was unquestionably different from the other usurper-emperors of the period in certain respects. Put simply, it is difficult to uphold a simple reading of Postumus and of his Gallic Empire as an ‘outsider’ entity, something completely foreign to imperial Rome, nor should it be thought of as an ‘insider’ territory either. In other words, the subjects of the Imperium Galliarum may have still considered themselves to be Romans and may have seen Postumus as the one legitimate emperor, but the fact remains that the division between the factions supporting the Gallic emperors and those of supporting the central emperors were explicitly enemies for a considerable number of years. Those living in the Gallic Empire’s territory, therefore, were still Roman in a certain sense, but they can not, after AD 260, have been ‘Roman’ in quite the same way that people living, for instance, in Italy or Spain were.

This brief summary of Postumus’ rule reveals that the Imperium Galliarum was a complex entity; while Postumus maintained certain Roman ideological and administrative institutions, his authority was based on his control over local resources and manpower within a clearly circumscribed territory. The Imperium Galliarum existed at once ‘inside’ traditional Roman imperial struc-tures, yet still ‘outside’ the authority of the central government. In order to test the precise extent to which Postumus’ Gallic Empire was unique within the context of the problems of the third century AD and, more importantly, to gain some sense of what caused Postumus’ Empire to take the shape that it did, it is necessary to briefly explore another case-study as a counterbalance to the first. This leads, then, to the next episode to be discussed here, namely the events that occurred in North Africa during AD 238, the ‘year of the seven emperors.’

AD 238 is notable for being typically understood as the beginning of the third century’s troubles, as the year which saw, among other things, the ascension of Gordian I and his sons to the emperorship at Rome.29 The problems of the year actually began three years earlier in AD 235 when the last of the Severan rulers, Severus Alexander, was murdered by a non-aristocratic soldier named Gaius Iulius Verus Maximinus, or Maximinus Thrax. Maximinus was the first of the so-called Soldatenkaiser and, as a non-elite usurper who had claimed the throne through violence, he was not accepted by the Roman ruling aristocracy.30 In AD 238, some of the leading Roman citizens living in Africa Proconsularis murdered the province’s procurator, then roused the elderly senator and former governor Marcus Antonius Gordianus, or Gordian I, out of retirement on his estate in Thysdrus, convincing him to revolt against Maximinus and to take the throne in Rome. Gordian’s supporters in Rome, in preparation of his arrival, murdered both the Praetorian and the Urban Prefects, and the senators in Rome declared Gordian emperor and defender of the Empire against the illegitimate usurper Maximinus.

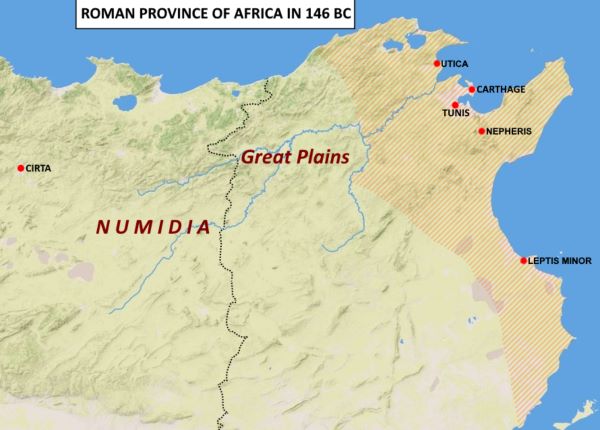

Meanwhile, with Gordian and his son, Gordian II, in Carthage getting ready to march on Italy, the legate of the African province of Numidia, a certain Capellianus, chose to oppose Gordian’s rebellion. As legate, Capellianus was in command of the soldiers of the Legio III Augusta, the sole legionary force in all of the Africa territory,31 and it was this force that he led into Proconsularis against Gordian and his supporters. Gordian’s son was killed in battle against Capellianus at Carthage, at which news the elder Gordian committed suicide. The senate in Rome, upon learning this, hailed the aristocrats Pupienus and Balbinus co-emperors along with Gordian’s grandson, thirteen-year-old Gordian III, as their junior Caesar. Maximinus then invaded Italy, but was murdered by his own troops during an unsuccessful siege of Aquileia. Shortly thereafter, Pupienus and Balbinus were also murdered by their own troops, leaving the young Gordian III as sole emperor, the seventh person hailed emperor that year. This left Capellianus alone in Africa without allies, and the young emperor temporarily disbanded the Legio III Augusta for their role in the death of his father and grandfather.32

Although none of the claimants to the throne during this year were able to hold on to power for any length of time apart from the young Gordian III, all of them, immediately upon being hailed emperor, assumed the trappings of a legitimate, traditional Roman emperor. In inscriptions, for instance, we see Gordian III with the traditional titles Imp(erator) Caes(ar) M(arcus) Antonius Gordianus Pius Felix Invictus Augustus.33 Even the first two Gordiani, although their rule was quite short lived, are addressed in surviving inscriptions using the appropriate titulature of an imperial dynasty.34 An interesting dedicatory inscription from Aigeai in Cilicia, probably dating to late in AD 238 or 239, refers to all three Gordiani together along with the entire Severan line. Clearly, this inscription is attempting to fit the usurper dynasty of the Gordiani into the legitimate line of succession of the previous ruling family which was, as the inscription seems to imply, interrupted by the illegitimate usurper Maximinus.35 Maximinus himself, of course, did not share this view of his reign, and there exist inscriptions hailing him with the traditional titulature as Imperator Caesar Caius Iulius Verus Maximinus Pius Felix Augustus Germanicus maximus Sarmaticus maximus Dacicus maximus, signifying him as a legitimate emperor and highlighting his military exploits.36 Further, all of the emperors of AD 238 issued coins that survive in fairly large quantities, especially those of Gordian III. These coins looked like the normal imperial Roman coinage, featuring the emperor’s bust on the obverse and reverse types that highlighted each emperor’s liberality, generosity, and faithful care of military matters and the prosperity of the Roman people.37

Much about this episode, thus, looks similar to the events surrounding the formation of the Gallic Empire, which, as mentioned, has led some scholars to treat both events as parts of the same, larger period of turmoil during the mid-third century AD. Indeed, in the African case, as with the latter Gallic one, usurpations of political authority by popular military leaders led to multiple claimants to imperial rule and civil fighting between their factions of support-ers. Likewise, all of the rulers during the ‘year of seven Emperors’ in AD 238 acted in the same fashion as previous emperors, adopting the normal imperial titles, appointing subordinate officers, and minting coins in their own image with messages highlighting their imperial authority and benefaction to the Roman people. All of which, again, was also done by Postumus and his fellow Gallic emperors.

Unlike with Postumus’ Empire, however, the civil fighting in Africa in AD 238 did not circumscribe central Roman authority in any meaningful way, nor did it lead to the establishment of a large stretch of territory governed separately from Rome for any sustained period. In short, Africa at no point stood ‘outside’ of the Empire to the extent that the Imperium Galliarum did, in terms of being an enemy of the central Roman Empire. The crucial question, then, is why not? Or, to put it another way, what were the central factors driving the divergent reactions that these two regions had to similar ideological and political circumstances? To answer this, a comparison between the regions must be made, focusing on the military, economic, and financial factors that impacted the period, in order to highlight the broader historical context in which these events occurred and out of which these periods of turmoil arose.

Military Differences

The first point of comparison I will address is the military environment in the two regions. As mentioned, the central basis of Postumus’ authority was his control over the considerable military resources of northern Europe, particularly the vast numbers of soldiers, bases, and forts along the Danubian frontier. Indeed, this part of the Empire had seen a steady influx of soldiers beginning already in the Antonine period from the Marcomannic Wars under Marcus Aurelius in the AD 160s.38 Clearly, the large number of soldiers that fell under Postumus’ command after the siege of Cologne in AD 260 allowed him to exercise and consolidate his authority over the territory occupied by these soldiers as well as to thwart Gallienus’ attempts at reunification. Nevertheless, the military might of the Imperium Galliarum cannot be analyzed in isolation, as though it sprang up simultaneously with Postumus’ rise to power. Rather, this military power was already an integral part of the northwestern part of the Empire from the late second century AD and became increasingly more powerful and important as emperors continued to send vast armies to the Germanic provinces over the course of the third century.

Given the importance of the army and the extent to which all emperors relied on the military to legitimate their rule, then, this great concentration of Rome’s military power in northwestern Europe beginning in the late Antonine period certainly would have had a splintering effect on the region already in the late second century. This is not to say that Postumus’ usurpation was inevitable, or even that a similar fracturing of the imperial state into a territory like the Imperium Galliarum could just as easily have occurred earlier, although this is certainly a possibility. I am arguing, however, that the high degree of military activity and the large number of soldiers settled in the Gallic and Germanic provinces from the late second century began the process of dislocating imperial authority in that region. The process of northeastern Gaul and western Germany falling ‘outside’ the central state’s sphere of control, in terms of military and political authority, was thus a long process of which Postumus was the culmination. Moreover, this was a fairly unique situation within the Empire, particularly in the western half.39 It seems highly likely, therefore, that this peculiar military situation was a precondition for the peculiar way that events in the region played out during the AD 260s.

The military situation in northern Europe, again, stands in stark contrast to that in the rest of the western Empire, particularly Africa. As noted above, the African provinces were relatively under-militarized throughout the imperial period, hosting only one legionary force for the entire region. The chief military duty of this legion seems to have been protecting and enforcing the borders of Roman control from the threat of invasion by largely nomadic Numidian tribes to the South.40 Even in the late second and throughout the third century AD, however, as the Danubian frontier as well as the border between Rome and Persia in Mesopotamia in the eastern half of the Empire saw prolonged periods of hostility and the concomitant influx of military power, Africa remained remarkably peaceful.41 In AD 238, then, when the region did experience a rare moment of instability and civil fighting, there were no pre-existing ‘fault lines’ pushing the region towards disintegration as there were a few decades later in Gaul as well as in Palmyra to the East due to the large presence of an independent basis of power, namely armies, to be exploited by local leaders.

Economic Differences

The military factor, thus, looms large as a potential causal force for the different experiences of the two cases under consideration here. A corollary to the military situation that also deserves some attention is the general economic well-being of the two regions at the time that turmoil arose. In Gaul, Germany, and also in Britain, the weakening of imperial authority that occurred over the course of the late second and throughout the third centuries AD, hastened by the heavy concentration of soldiers in the region, was also attended by a weakening of economic productivity. It is difficult to say whether the military factor was the primary cause of the troubles and the economic secondary, or vice versa. Likely, the two issues were reinforcing.

It is clear, however, that Gallic production of export goods tapered off significantly during the mid to late second century AD. This is seen most clearly from the ceramic evidence. Gaul and, to a lesser extent, Britain, had been active centers for producing ceramics, both fine-ware and transport amphorae, for local as well as inter-regional distribution in the first and early second century AD. This production, though, fell off considerably in the later part of the second century and was nearly absent for most of the third, except for limited production restricted to regional distribution.42 While it is, admittedly, difficult to tie ceramic manufacturing directly to other aspects of the economy, it is undeniable that there is a strong relationship between the ability to produce a surplus of goods that are transported in ceramics to other regions, on the one hand, and general economic well-being, on the other. It is undeniable also, then, that the Gallic and Germanic provinces, along with Britain, suffered from a significant decline in productivity and in export trade at the same time as the disruptive presence of large numbers of soldiers were flooding into these regions. Notably, the only areas of northwestern Europe which maintained any significant ceramic production during the period were southern Gaul, namely the province of Narbonensis, and Baetica in Spain, the two areas in which the Gallic emperors had the most trouble maintaining power.43 The economic situation thus combined with the military in creating fault lines pushing the area further and further ‘outside’ of the control of the central Roman authority for several decades before Postumus came on the scene.

Again, the experience of Africa in this regard is quite opposite from that of northern Europe. Ceramics made in Africa feature fairly prominently in assemblages throughout the Mediterranean beginning in the late second century AD and lasting until Late Antiquity.44 This includes particularly fine-wares, which make up a significant portion of the ceramic material from the Eastern Mediterranean, as well as, to a lesser extent, the amphorae made in the region to transport the products of African agricultural production, notably olive oil, wine, and garum.45 Not only did the African economy survive the turmoil of the third century AD that ravaged so many parts of the Empire, but by all indications African production actually grew during this time. Indeed, new centers of ceramic production established in the third and early fourth centuries have been identified particularly in the interior parts of Africa Proconsularis. The region similarly saw a great amount of urban growth along with the development of non-agricultural economic activities such as textile manufacture and fish-salting.46 Crucially, moreover, much of this African production was geared for export, judging at least by the ceramic evidence, meaning that a significant part of Africa’s economic prosperity at the time was tied inextricably to their connection to the rest of the Roman world.

When a group of wealthy Roman aristocrats convinced Gordian I to come out of retirement in order to lead a rebellion against the emperor Maximinus, then, they did so in an environment with a thriving economy dependent on maintaining links to and interaction with the other areas under the control of the central Roman state. These aristocrats, the same elite Romans who held much of the land on which Africa’s crops were produced and who were the main force behind the development of the region’s ceramic and urban industries, thus had little incentive to support or encourage any act of separation from the rest of the Empire.47 I do not mean to imply that Gordian or his supporters were necessarily basing their plans explicitly on these economic considerations, but it would be equally foolish to deny that the fact that many of Africa’s elite owed much of their wealth and, thereby, their position to the region’s surplus production and economic links with the rest of the Mediterranean factored into the decisions made during this tense time.48

It is notable too, and undeniable, that as a result of the decisions made by Gordian and his supporters, whatever their individual motivations or concerns actually were, the African economy continued to operate uninterrupted and even to expand for the next century or so. Even the invasion of Proconsularis with the Legio III Augusta by Capellienus, although it resulted in outright civil violence and the disarmament of the legion, did nothing to alter the region’s economic life, nor, equally important, its political and social stability; in other words, its ‘insideness’. It seems that only a major, catastrophic event would have been able to disrupt Africa’s cohesion and ties to the central Roman state during the third century AD, a very different context than the one in Gaul and Germany where the region seems to have been ripe for a major dislocation of imperial authority.

Financial Differences

The differences in military activity and economic prosperity noted above had another major effect that deserves attention here, namely in terms of the broad financial stability of the different regions. The financial changes of the period are seen best by studying the coinage that circulated in the different regions at the time. The ideological force of the coinage produced by the Gallic emperors as well as the several claimants to the throne of AD 238 has been discussed already. Certainly these coins served to reinforce and spread an image of the emperor issuing them as the supreme power for the whole, unified Roman world and the people under his authority. The financial impact of Roman coins, however, must not be overlooked. The significance of developments in the Roman currency system for the purposes of this article is that the changes made to the coinage and their broader impact on other aspects of Roman life were also experienced with regional differences.

As mentioned, Postumus issued a vast number of coins during his reign, mainly billon antoniniani,49 but also small amounts of true bronze coins, particularly a double sestertius. Like much of the other economic material produced in the Imperium Galliarum during this period, the coins of the Gallic Empire had almost an exclusively regional circulation within the Gallic territory.50 Postumus issued so many coins, it seems, primarily to pay the troops upon whom he relied heavily as his basis of power and authority.51 Indeed, one of the major advantages Postumus held in the territory of the Imperium Galliarum was his control of the mints at Cologne and at Trier. This allowed him to pro-duce the large quantity of coinage he needed to continually furnish his supporters with largess. In Africa, conversely, there had been no local minting of coinage since the production of some bronze coins under emperor Tiberius in the mid first century AD.52 Neither Gordian I, nor Capellienus, nor any other ambitious Roman in Africa therefore had the opportunity to appropriate any minting facilities from the central state and redirect coin production for their own purposes, as Postumus was able to do. All of the coinage produced by the emperors of AD 238 was minted in Europe, mainly at Rome.53

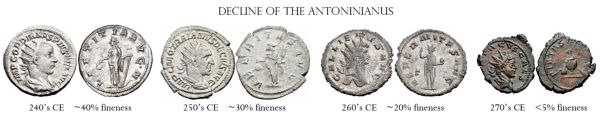

Furthermore, not only did Postumus and the other Gallic emperors produce vast quantities of coinage, but their coins were of rather low value. The billon antoninianus, the primary type produced by the Gallic emperors, was first introduced under Caracalla as a cost-saving effort for the Roman treasury in around AD 215.54 At this time, the Roman authorities were suffering from a shortage in precious metal, as many of the main sources of silver had begun to dry up in the late second century.55 The antoninianus was mainly a bronze coin, made from much cheaper and more abundant metals, and contained only small amounts of silver. The financial importance of the coin is that antoniniani were tariffed at twice the value of the pure-silver denarius that had been the backbone of the Roman currency system since the reforms of Augustus, yet they contained only one and a half times the silver as old denarii. Antoniniani, thus, allowed the state to increase the amount of money in circulation dramatically while conserving precious silver reserves as much as possible.

The reasons for the introduction of this overvalued coin under Caracalla seem to be the result not only of the dwindling supply of silver, but also of increasing costs to the Roman state, particularly in the form of payment and largess distributed to soldiers. It has been noted above that the late Antonine period saw a steady increase in military activity in certain regions of the Empire. This increased activity led to an increase both in the number of soldiers supported by Rome, but also spurred both Septimius Severus and Caracalla to increase military pay and to bestow great financial benefits in order to recruit and retain loyal soldiers, mainly in the form of praemia and donativa.56 The minting of antoniniani was abandoned shortly after they were introduced, as they were largely rejected by coin users for being too overvalued. In the AD 230s, however, the same pressures that led Caracalla to introduce the billon coinage were further exacerbated by continually dwindling silver supplies as well as by persistent military conflicts in the North and in the East. Moreover, the beginning of the ‘Soldatenkaiser’ period in which military leaders were constantly competing with each other for power by bestowing financial benefits on their supporters, mainly the troops under their command, likewise put pressure on already taxed monetary resources. The antoninianus was, therefore, reintroduced and, from the AD 230s until Aurelian’s currency reforms in the mid-270s, antoniniani were produced in very large numbers with ever decreasing amounts of silver.57

Again, the introduction of the antoninianus was sparked by financial prob-lems which began in the late second century AD, but the creation of a billon currency was not the first manipulation of the currency the Roman state undertook in an attempt to combat these problems. Even before AD 215 when the antoninianus was first minted, the two principal denominations circulating within the Empire, the silver denarius and the bronze-orichalcum sestertius, underwent a series of debasements.58 The impact of these debasements, however, was unevenly felt. For the bronze coins, I have demonstrated elsewhere that sestertii minted at Rome and found in Gaul and in Britain were being minted at increasingly lower weights beginning already in AD 161.59 Conversely, the same type of coins which ended up in Africa and Spain did not begin losing weight until later, and even then the debasement of coins found in these regions occurred at a much lower rate than those from the northern provinces. This is not the place to engage in a lengthy discussion of the mechanisms behind this regionalism in currency debasement, but let it suffice to note here simply that it is a clear indication that the financial and economic problems driving debasement as well as the eventual introduction of a billon currency were more severe in northern Europe than in the southern Mediterranean. Further support for this notion of regionalism in financial crises and currency manipulations comes from the antoniniani themselves; the vast majority of antoniniani produced in the mid-third century AD that survive today were found in Gaul, Germany, and Britain, the very areas controlled by Postumus.60 Similarly, not only are antoniniani finds relatively scarce in Africa, but these coins do not begin showing up in African hoards until the late 250s.61

This all caused what can only be described as a fracturing of the western Empire into distinct monetary zones which matched the different military and economic areas discussed previously: the relatively early and severe debasement of the traditional denominations along with the early introduction of the antoninianus in the northwestern zone; and the continued use of the traditional denominations at relatively stable weights and values in southern Europe and Africa. The ‘solutions’ attempted by the Roman state to solve the issues facing them in northern Europe, moreover, only exacerbated the prob-lems. Debasement and the introduction of the overvalued billon antoninianus were intended to allow the state to expand the number of coins in circulation drastically without a similarly sharp rise in the amount of precious metal being used. This increase in coinage, which, again, was aimed primarily at the regions with the largest concentrations of soldiers in northern Europe and in the East, led also to an inflationary period in these same areas, certainly monetary inflation if not also price inflation.62 It has been noted too that Gaul saw a vast increase in imitation of both antoniniani and sestertii during this period, particularly under the Gallic emperors, another sign that the currency manipulations of the time were not able to adequately supply people’s requirements for usable, good quality coins, leading to serious and widespread tensions in the financial system of northern Europe generally.63

Indeed, it is possible that this inflationary spike was instrumental also in the decline of economic production in the affected areas noted above. For, the debasements and increase in number of coins circulating would have caused the intrinsic value of the coins to constantly change, as would the influx of a great quantity of low-quality imitation coins, making investing and loaning money a highly risky proposition. With a decline in investment and loan-ing, moreover, there would follow a decline in the production supported by such investment. There does, in fact, seem to have been a general trend away from investment and the establishment of endowment funds over the course of the third century AD leading into the early fourth century, when the successive deflationary reforms of Aurelian and Diocletian reestablished some semblance of financial order.64 Again, the contrast with Africa is striking. That region was able not only to maintain a high degree of economic activity, but even further to develop its productive capacity during this time, phenomena which required large amounts of investment and, thus, a stable economic and financial environment. This economic prosperity was, therefore, inextricably linked with the relatively stable and high quality currency that continued to circulate in the region, itself tied up with the relative lack of a large, disruptive military force in the area.

Conclusion

The preceding pages illuminate that the problems, or ‘crises’, which afflicted Gaul in the AD 260s and Africa in AD 238 did not sprout up suddenly in the middle of the century, but rather were largely the product of a series of disruptive factors whose origins stretched back to the late Antonine period. It is, as far as I can ascertain, fairly novel to suggest that long-term differences in the aspects of Roman life that I identify as the key factors affecting the period—namely military activity, economic productivity, and financial stability—had a significant impact on the manner in which the events of the third century unfolded. Yet, as I have illustrated in this article through a direct comparison of these two regional case studies, many of the vital political and strategic decisions made by the various actors involved in the episodes discussed here were based in part on the military, economic, and financial settings in which they acted. In other words, these factors and the contexts they created set the stage for the particular type of political upheaval, usurpations of central authority, and civil warfare that occurred in northwestern Europe as well as in North Africa during the mid-third century AD, respectively.

In the Gallic and Germanic provinces, Postumus came to power in an environment that had experienced nearly one hundred years of military turmoil and the financial problems associated with a heavy concentration of troops who were receiving increasingly generous imperial compensation for their support. Postumus seized upon the opportunity offered by the anger of his troops at the imperial authorities in AD 260 by leading them in the murder of the Praetorian Prefect and the capture and pillaging of Cologne. He then continued to furnish his loyal troops with financial rewards for their support for the rest of his rule, a policy followed by nearly all emperors at least since Septimius Severus and one that persisted into the fourth century AD. In part, the troops’ anger about their treatment by the Prefect and the isolation of the central state authorities in the region were products of a protracted period of disruption and dislocation in the normal functioning of the regions’ military, economic, and financial institutions, although the Gallic emperors took great pains to maintain certain ideological and political continuities with their imperial Roman past. Moreover, Postumus’ need for continual supplies of coinage to reward his soldiers’ loyalty only exacerbated these preexisting problems, leading to a further strengthening of the position of soldiers as well as to further debasements, inflation, and economic decline. Only with the reunification of central Roman authority by Aurelian in AD 274, coupled with his drastic reforms of the Roman currency system, primarily a deflationary measure, did the region begin to recover from the problems that had begun in the AD 160s.

This is why North Africa in AD 238 makes such an interesting case study; that year likewise saw coups by popular military leaders, multiple claimants to power who each reiterated the traditional symbols and activities of legitimate emperors, as well as military turmoil remarkably similar to the events which led to Postumus’ rule. Yet, Africa saw nothing close to the fracturing of the Roman state that occurred in the AD 260s. Since the late second century AD, while most of the Roman world was beginning to experience the military, political, and economic problems that would plague most of the Empire until the early fourth century, Africa remained remarkably stable. The region was largely peaceful and certainly under-militarized compared to northern Europe, it maintained and advanced a high degree of economic productivity and prosperity, and even the financial situation remained much healthier there than in the North. The political disruptions and civil fighting which did occur in the area during AD 238, then, confronted a vibrant and united region able to with-stand a fairly large amount of turmoil without busting at the seams.

Admittedly, there are a few potential problems with the arguments I put forward in this article. Firstly, a somewhat obvious and much more simple answer to the question of why the two case studies are different than what I suggest here could be offered. It might be argued simply that, in the African case, Gordian was considered the legitimate emperor by the senate in Rome, while Postumus was labeled a true usurper opposed by the senate and the central emperor Gallienus. Yet, this simple answer does not hold up to close scrutiny, for in the case of AD 238 Maximinus was, like Postumus, a military leader from northern Europe who led his troops in revolt of the central authorities and claimed power for himself. Maximinus, however, did not consolidate the territory under his control as Postumus later did, but immediately began ruling as though he held authority over a unified Empire. Nor, as far as we can tell from the available evidence, did Capellianus call himself emperor or try to consolidate his hold over Africa, even though he had control of the only army in the region and led a violent revolt against the legitimate central rulers, the Gordiani. Thus, the crucial point is that in both instances we see usurpers from northern Europe opposed by the senate in Rome, yet these usurpers act very differently. Additionally, in the case of Capellianus, we see someone who is put in the same position as other usurpers, yet who chose not to claim imperial authority. The factors I have identified here, then, remain essential to address the reason that these different actors behaved so differently at similar events.

Another simple answer to the difference between the case studies would be that the timing of the two episodes accounts for the difference. Namely, that in AD 238 the Roman world was still too wedded to the concept of a single, unified Empire to allow for the sort of fractioning that occurred in the AD 260s with not only Postumus, but with Odaenathus’ Palmyrene Empire as well. This is, however, to skirt the issue rather than address it, for such an interpretation nevertheless begs the question of exactly what changed between AD 238 and 260 that allowed for a similar impetus, namely the violent revolt against the central Roman authorities by a popular military leader, to result in a fragmentation of the Empire in the one case but not in the other. Thus, the answer is much more complicated than it might at first appear and, as I demonstrate in this article, seems to have more to do with the divergent circumstances and structural realities surrounding Africa in AD 238 and those in northwestern Europe in the late 250s and 260s than with any individual’s whims or broad chronological developments.

Finally, it needs to be stressed again that I am in no way trying to diminish the role of Postumus’ personal ambition or individual action in creating the Imperium Galliarum. Nor am I suggesting that his Empire was a completely foreign state, distinct from and unrecognizable to a Roman population. I note above how, in many ways, Postumus styled himself as a traditional, legitimate Roman emperor ruling over a Roman territory and a Roman people. He was, moreover, largely successful in this goal, and for most of the people living in the Gallic Empire’s territory, life went on largely as it had before Postumus’ usurpation. It is necessary to keep in mind, however, that life in the region had been going on in an increasingly fragmented manner, isolated from the rest of the Roman world, since the Antonine period. The main point I wish to get across, then, is that, in spite of certain continuities with traditional Roman practice and regardless of whether or not Postumus intended to eventually march on Rome and rule over a truly united Empire as Maximinus had done earlier, there was something unique about the experiences of northwest Europe even in the context of the turbulent third century. Crucially, the only way to draw out with any precision or clarity the exact nature of this difference and, more interestingly, what may have been the main causes of why the region experienced the period the way that it did is by comparing Gaul with a different area that underwent similar events, yet experienced them differently.

I offer in this article, then, a different look at some of the crucial factors and issues impacting the western Roman Empire during the third century AD, one of the more turbulent and problematic periods in Roman history. Certainly, it is not possible to do justice to this complex period in the short space of this article. Still, direct comparison of the key factors explored here provides a more nuanced understanding of the complex events explored as case studies in this article, highlighting the way that different aspects of Roman society progressed along different paths; how ideological and political continuities in Gaul coexisted with broad dislocations due to military, economic, and financial developments; while in Africa, deep seated ideological, economic, and financial stability were able to overcome political turmoil and civil fighting to maintain ties with the wider Roman world throughout this tumultuous period. These two important regions in the western Empire were in certain respects at once both ‘outside’ and ‘inside’ the traditional structures of imperial Roman life. Still, in order to fully understand this crucial period in the history of the Roman Empire, it is necessary to determine how the various factors—political, ideological, military, economic, and financial—affected the regions differently during this period and thereby to identify some of the deep, structural roots which underlay the divergent experiences of these two regions in the third century AD.

Endnotes

- I would to thank the conference organizers for inviting me to present my work. I would also like to thank Mike Peachin and Inger Kuin for their very helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article, as well as the other conference participants who offered valuable feedback.

- The focus on these factors is supported by theoretical work in sociology, notably Mann’s theory about the sources of political power, known as the IEMP model. The basic formulation of Mann’s theory is that “[a] general account of societies, their structure, and their history can best be given in terms of the interrelations of what I will call the four sources of social power: ideological, economic, military, and political (IEMP) relationships.” Michael Mann, The Sources of Social Power, vol. I. (Cambridge, 1986), 2. Similarly, in recent years Turchin has advocated the need to explore the deep roots of important political and social developments in order to properly delineate long-term historical processes, terming this endeavor Cliodynamics. Peter Turchin, “Toward Cliodynamics—an Analytical, Predictive Science of History,” Cliodynamics 2/1 (2011).

- A useful and recent survey of this notion in modern scholarship is provided by Wolf Liebeschuetz, “Was There a Crisis of the Third Century?,” in Crises and the Roman Empire: Proceedings of the Seventh Workshop of the International Network Impact of Empire, Nijmegen, June 20–24, 2006 Olivier Hekster, Gerda de Kleijn, and Daniëlle Slootjes (Leiden, 2007), 11–20.

- Edward Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, ed. Hans-Friedrich Müeller (New York, 2003), pp. 58–212; Michael Ivanovitch Rostovtzeff, The Social and Economic History of the Roman Empire, ed. Peter M. Fraser (Oxford, 1998), pp. 469–501. Georges Depeyrot, “Crise économique, formation des prix, et politique monétaire au troisième siècle après J.-C.,” Histoire & Mesure 3/2 (1988), 235–47. Géza Alföldy, (Stuttgart, 1989), pp. 464–90. Dominique Hollard, “La circulation monétaire en Gaul au IIIe siècle après J.-C,” in Coin Finds and Coin Use in the Roman World, ed. Cathy E. King and David G. Wigg (Berlin, 1996), 203–17. Ramsay MacMullen, Roman Government’s Response to Crisis, A.D. 235–337 (New Haven, 1976), pp. 195–213. Jean-Michel Carrié, “Solidus et credit: qu’est-ce que l’or a pu changer?,” in Credito e moneta nel mondo romano: atti degli Incontri capresi di storia dell’economia antica : Capri, 12–14 ottobre 2000, ed. Elio Lo Cascio (Bari, 2003), 265–79 likewise describe the many crises faced by Rome during the third century, but focus instead on how these crises were overcome under the Tetrarchy.

- A recent and important example is David S. Potter, The Roman Empire at Bay: AD 180–395 (London, 2004), pp. 263–98.

- Christian Witschel, Krise, Rezession, Stagnation?: Der Westen Des Römischen Reiches Im 3. Jahrhundert N. Chr (Frankfurt, 1999), pp. 375–7. cf. Lukas de Blois, “The Military Factor in the Onset of Crises in the Roman Empire in the Third Century AD,” in The impact of the Roman army (200 BC–AD 476), economic, social, political, religious, and cultural aspects : proceedings of the Sixth Workshop of the International Network Impact of Empire (Roman Empire, 200 B.C.–A.D. 476), Capri, March 29–April 2, 2005, ed. Lukas de Blois et al. (Leiden, 2007), 497–507. De Blois follows Witschel’s model of regionalism in describing the increasingly disruptive crises during the period AD 230 to 284.

- Marcel Le Glay, Grandeur et chute de l’Empire (Paris, 2005), pp. 251–2.

- These are the ‘barracks’ or ‘soldier’ emperors; short lived rulers during the mid-third century who mainly came from relatively low-ranking military positions to claim the emperorship. Not all emperors during this period, though, fit this description and the term used here is meant simply to denote the chaotic period in which numerous claimants to ultimate power came forward backed by factions of the Roman military.

- Zosimus 1.38.2.

- The most comprehensive account of this period remains John F. Drinkwater, The Gallic Empire Separatism and Continuity in the North-Western Provinces of the Roman Empire, A.D. 260–274 (Stuttgart, 1987). For useful, more recent summaries of the events, see Potter, The Roman Empire at Bay; Andreas Luther, “Das Gallische Sonderreich,” in Die Zeit Der Soldatenkaiser: Krise Und Transformation Des Römischen Reiches Im 3. Jahrhundert N. Chr. (235–284), ed. Klaus-Peter Johne, Udo Hartmann, and Thomas Gerhardt (Leiden: Brill, 2008), 11–20.

- Luther, “Das Gallische Sonderreich,” p. 329.

- Werner Eck, “Das Gallische Sonderreich: Eine Einführung zum Stand der Forschung,” in Die Krise des 3. Jahrhunderts n. Chr. und das Gallische Sonderreich: Akten des interdisziplinären Kolloquiums Xanten 26. bis 28. Februar 2009, ed. Thomas Fisher (Wiesbaden, 2012), 63–84.

- Ingemar König, Die gallischen Usurpatoren von Postumus bis Tetricus (München, 1981), pp. 125–31. Drinkwater, The Gallic Empire Separatism and Continuity in the North-Western Provinces of the Roman Empire, A.D. 260–274, pp. 30–4. Potter, The Roman Empire at Bay, p. 263. Andreas Goltz and Udo Hartmann, “Velerianus und Gallienus,” in Die Zeit Der Soldatenkaiser: Krise Und Transformation Des Römischen Reiches Im 3. Jahrhundert N. Chr. (235–284), ed. Klaus-Peter Johne, Udo Hartmann, and Thomas Gerhardt (Leiden, 2008), 223–96, pp. 287–92. Eck, “Das Gallische Sonderreich,” p. 68.

- König, Die gallischen Usurpatoren von Postumus bis Tetricus, pp. 148–52. Potter, The Roman Empire at Bay, p. 266.

- Potter, The Roman Empire at Bay, p. 263 describes the Roman world as “fractured into three parts” during the latter parts of the third century, with the Palmyrene Empire of Odaenathus and his descendants having a similar rupturing effect on the Roman Empire as the Imperium Galliarum.

- Notably Drinkwater, The Gallic Empire Separatism and Continuity in the North-Western Provinces of the Roman Empire, A.D. 260–274, pp. 240–8. Andreas Johne, Klaus-Peter, Udo Hartmann, and Thomas Gerhardt, “Einleitung,” in Die Zeit Der Soldatenkaiser : Krise Und Transformation Des Römischen Reiches Im 3. Jahrhundert N. Chr. (235–284), ed. Klaus-Peter Johne, Udo Hartmann, and Thomas Gerhardt (Leiden, 2008), 5–12. Luther, “Das Gallische Sonderreich,” pp. 340–1. See also de Blois, “The Military Factor in the Onset of Crises in the Roman Empire in the Third Century AD” on the specific role played by the military in the problems of the third century.

- Eck, “Das Gallische Sonderreich,” pp. 63–70.

- See notably Karlheinz Dietz, Senatus contra principem: Untersuchungen zur senato-rischen Opposition gegen Kaiser Maximinus Thrax (München, 1980). König, Die gal-lischen Usurpatoren von Postumus bis Tetricus. Drinkwater, The Gallic Empire Separatism and Continuity in the North-Western Provinces of the Roman Empire, A.D. 260–274. Potter, The Roman Empire at Bay. Luther, “Das Gallische Sonderreich.” Eck, “Das Gallische Sonderreich.”

- Notable proponents of the former view are Drinkwater, The Gallic Empire Separatism and Continuity in the North-Western Provinces of the Roman Empire, A.D. 260–274. Potter, The Roman Empire at Bay. For the opposite view, see especially Eck, “Das Gallische Sonderreich.”

- Kenneth W. Harl, Coinage in the Roman Economy, 300 B.C. to A.D. 700 (Baltimore, 1996), p. 145. Potter, The Roman Empire at Bay, p. 261.

- Potter, The Roman Empire at Bay, p. 260. Eck, “Das Gallische Sonderreich,” pp. 66–74.

- For instance, CIL 2.4943 (= ILS 562), a milestone from Acci in Spain.

- For the coin types issued by the Gallic emperors, see the Roman Imperial Coinage vol. 5 part 2. See also notably Pierre Bastien, “La trouvaille de Guiscard (monnaies de bronze de Postume),” Revue numismatique 6/4 (1962), 232–36. Edward Besly and Roger Bland, The Cunetio Treasure: Roman Coinage of the Third Century AD (London, 1983). Drinkwater, The Gallic Empire Separatism and Continuity in the North-Western Provinces of the Roman Empire, A.D. 260–274, pp. 135–214. More recently, Daniel Gricourt and Dominique Hollard, “Les productions monétaires de Postume en 268–269 et celles de Lélien (269). Nouvelles propositions,” The Numismatic Chronicle 170 (2010), 129–204.

- Luther, “Das Gallische Sonderreich,” pp. 338–40. Eck, “Das Gallische Sonderreich,” p. 74. See above, note 21, for an inscription in which Postumus is noted as being the consul, the pontifex maximus, a proconsul, as well as having tribunician power.

- AE 1993.1231. The inscription is used also by Potter, The Roman Empire at Bay, p. 256 and Eck, “Das Gallische Sonderreich,” p. 66 to demonstrate that the Imperium Galliarum was an entity distinct from the rest of the Roman state.

- For useful overviews concerning Roman numismatic iconography, see notably Andrew Burnett, Coinage in the Roman World (London, 1987), pp. 66–85. ibid., Coins (London, 1991), pp. 38–9. Harl, Coinage in the Roman Economy, 300 B.C. to A.D. 700, pp. 74–7. Nathan T. Elkins, “Coins, Contexts, and an Iconographic Approach for the 21st Century,” in Coins in Context I: new perspectives for the interpretation of coin finds ed. Hans-Markus von Kaenel and Fleur Kemmers (Mainz, 2009), 25–46.

- William E. Metcalf, “The Emperor’s Liberalitas: Propaganda and the Imperial Coinage,” Rivista Italiana Di Numismatica E Scienze Affini 95 (1993), 337–46. Carlos F. Noreña, “The Communication of the Emperor’s Virtues,” Journal of Roman Studies 91 (2001), 146–68. Andrew Meadows and Jonathan Williams, “Moneta and the Monuments: Coinage and Politics in Republican Rome,” Journal of Roman Studies 91 (2001), 27–49. Olivier Hekster, “Coins and Messages. Audience Targeting on Coins of Different Denominations?” in Representation and Perception of Roman Imperial Power, ed. Lukas de Blois et al. (Amsterdam, 2003), 20–35. Georges Depeyrot, La propagande monétaire (64–235) et le trésor de Marcianopolis (251) (Wetteren, 2004). Volker Heuchert, “The Chronological Development of Roman Provincial Coin Iconography,” in Coinage and Identity in the Roman Provinces, ed. Christopher J. Howgego, Volker Heuchert, and Andrew Burnett (Oxford, 2005), 29–56. Elkins, “Coins, Contexts, and an Iconographic Approach for the 21st Century.”

- Eck, “Das Gallische Sonderreich,” p. 81.

- The best source for the events of AD 238 remains Herodian, with the Historia Augusta and Zosimus providing some useful material as well. For a somewhat more complete summary of the period than I provide here, most useful is Potter, The Roman Empire at Bay, pp. 167–72. See also Arbia Hilali, “Le crise de 238 en afrique et ses impacts sur l’Empire romain,” in Crises and the Roman Empire: Proceedings of the Seventh Workshop of the International Network Impact of Empire, Nijmegen, June 20–24, 2006, ed. Olivier Hekster, Gerda de Kleijn, and Daniëlle Slootjes (Leiden, 2007), pp. 57–65 specifically on the activity in Africa.

- On the senatorial opposition to Maximinus during this period, see particularly Dietz, Senatus contra principem: Untersuchungen zur senatorischen Opposition gegen Kaiser Maximinus Thrax, pp. 333–6.

- On Africa’s military situation, see notably Elizabeth W.B. Fentress, Numidia and the Roman Army: Social, Military and Economic Aspects of the Frontier Zone (Oxford, 1979). Yann Le Bohec, La troisième Légion Auguste (Paris, 1989). Pierre Morizot, “Impact de L’armée Romaine Sur L’économie de l’Afrique’,” in The Roman Army and the Economy, ed. Paul Erdkamp (Amsterdam, 2002), pp. 345–74.

- It is worth noting, though, that the legion was reformed under the emperor Valerian in the AD 250s and continued its main role of guarding the African limes against invading nomadic tribes.

- AE 1987.1090b (= IL Afr. 614), a dedicatory inscription of a balineum restored by the emperor from Volubilis in modern-day Morocco.

- For instance, in a fragmentary inscription from Palaestina [AE 1978.826] Gordian I is hailed as Imperator, Pius, Felix, and Augustus.

- SEG 32.1312.

- See, for an example, a dedicatory inscription [AE 2007.1713 (=IL Afr. 661)] honoring both Maximinus and his son for rebuilding collapsed bridges in Masclianae in Africa Proconsularis, heartland of the Gordiani and their supporters.

- See Roman Imperial Coinage vol. 4, part 2 for the coin types of this period.

- On these wars see especially András Mócsy, Pannonia and Upper Moesia: A History of the Middle Danube Provinces of the Roman Empire (Boston, 1974). Péter Kovács, Marcus Aurelius’ Rain Miracle and the Marcomannic Wars (Leiden, 2009). For the military aspect of the third century crises generally, see notably de Blois, “The Military Factor in the Onset of Crises in the Roman Empire in the Third Century AD.”

- As mentioned, frequently a comparison is made between Postumus’ territory and the Palmyrene Empire of Odaenathus and, after his death, his wife Zenobia and their son Vaballathus. The similarity between these cases extends beyond the mere fact that they are both often considered breakaway kingdoms; Palmyra was as much an exception in the East as northern Gaul and Germany were in the West. For, like the Danubian provinces, Palmyra was on the outskirts of Roman territory and had seen a large influx of soldiers over the course of the third century due to Roman battles against the Parthian and Sasannid Persians to the East. The main difference is that Odaenathus was granted authority by Gallienus, whom Odaenathus likewise recognized as the legitimate emperor, and it was only after his death in AD 270 that his wife Zenobia revolted from the cen-tral authority and the Palmyrene territory became a truly independent entity. On this, see notably Potter, The Roman Empire at Bay, pp. 257–68. Peter M. Edwell, Between Rome and Persia: The Middle Euphrates, Mesopotamia and Palmyra under Roman Control (New York, 2008), pp. 63–92. Andrew M. Smith, Roman Palmyra: Identity, Community, and State Formation (Oxford, 2013), pp. 175–81.

- Le Bohec, La troisième Légion Auguste, p. 573.

- On the general stability of North Africa throughout the third century: Robert Turcan, “Le trésor de Guelma: étude historique et monétaire” (Paris, 1963), pp. 25–35. Marcel Bénabou, La résistance africaine à la romanisation (Paris, 1976), pp. 214–40. Fentress, Numidia and the Roman Army, p. 117. Claude Lepèlley, “l’Afrique,” in Rome et l’intégration de l’Empire: 44 av. J.-C.-260 ap. J.C., tome 2: Approche régionales du Haut-Empire, ed. Claude Lepèlley (Paris, 1998), 71–112, pp. 105–9. Claude Lepelley, “The Survival and Fall of the Classical City in Late Roman Africa,” in The City in Late Antiquity, ed. John Rich (New York, 1992), 50–76, p. 55. David Cherry, Frontier and Society in Roman North Africa (Oxford, 1998), pp. 58–66.

- Michael Fulford, “Territorial Expansion and the Roman Empire,” World Archaeology 23/3 (1992), 294–305. Christopher J. Going, “Economic ‘Long Waves’ in the Roman Period? A Reconnaissance of the Romano-British Ceramic Evidence,” Oxford Journal of Archaeology 11/1 (1992), 93–117. Paul Reynolds, “Trade Networks of the East, 3rd to 7th Centuries: The View from Beirut (Lebanon) and Butrint (Albania)(fine Wares, Amphorae and Kitchen Wares),” in LRCW 3. Late Roman Coarse Wares, Cooking Wares and Amphorae in the Mediterranean: Archaeology and Archaeometry. Comparison between Western and Eastern Mediterranean, ed. Simoneta Menchelli et al. (Oxford, 2010), 89–114. Tamara Lewit, “Dynamics of Fineware Production and Trade: The Puzzle of Supra-Regional Exporters,” Journal of Roman Archaeology 24 (2011), 313–32.

- Pedro Paulo Abreu Funari, “Baetica and the Dressel 20 Production An Outline of the Province’s History,” Dialogues D’histoire Ancienne 20/1 (1994), 87–105, pp. 94–5.

- David P.S. Peacock, Fathi Bejaoui, and Nejib Ben Lazreg, “Roman Amphora Production in the Sahel Region of Tunisia,” in Amphores romaines et histoire économique: dix ans de recherché (Rome, 1989). ibid., “Roman Pottery Production in Central Tunisia,” Journal of Roman Archaeology 3 (1990), 59–84. Simon Keay, “African Amphorae,” in Cerámica in Italia: VI–VII Secolo. Atti Del Convegno in Onore Di John W. Hayes, ed. Lucia Saguí (Rome, 1998), 141–55. Elizabeth Fentress et al., “Accounting for ARS: Fineware and Sites in Sicily and Africa,” in Side-by-Side Survey: Comparative Regional Studies in the Mediterranean World, ed. Susan Alcock and John F. Cherry (Oxford, 2004), 147–62. Michel Bonifay, “La céramique africaine, un indice du développement économique?,” Antiquité Tardive 11/1 (2004), 113–28; ibid., “Observations sur la diffusion des céramiques africaines en Méditerranée orientale durant l’antiquité tardive,” in Mélanges Jean-Pierre Sodini, ed. François Baratte (Paris, 2005), 565–81. J. Theodore Peña, “The Quantitative Analysis of Roman Pottery: General Problems, the Methods Employed at the Palatine East, and the Supply of African Sigillata to Rome,” in Supplying Rome and the Empire, Proceedings the International Seminar “Rome, Provinces, Production and Distribution” Held at Siena-Certosa Di Pontignano (May 2–4, 2004), ed. Emanuele Papi (Providence, 2007), 153–72. John W. Hayes, The Athenian Agora: Results of Excavations Conducted by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. vol. 32, (Princeton, 2008). Philip Bes and Jeroen Poblome, “African Red Slip Ware on the Move: The Effect of Bonifay’s Etudes for the Roman East,” in Studies in Roman Pottery of the Provinces of Africa Proconsularis and Byzacena (Tunisia), ed. John H. Humphrey (Providence, 2009), 73–91.

- Andrew Wilson, “Marine Resource Exploitation in the Cities of Coastal Tripolitania,” in L’Africa Romana XIV, vol. 1, ed. Mustapha Khanoussi, Paola Ruggeri, and Cinzia Vismara (Rome, 2002), 429–36. Jean-Pierre Brun, Archéologie du vin et de l’huile dans l’Empire romain (Paris, 2004). David Mattingly, “A New Study of Olive Oil (and Wine?) Production in Northern Tunisia,” Journal of Roman Archaeology 22 (2009), 715–20. Annalisa Marzano and Giulio Brizzi, “Costly Display or Economic Investment? A Quantitative Approach to the Study of Marine Aquaculture,” Journal of Roman Archaeology 22 (2009), 215–30.

- Clementina Panella, “Le anfore di età imperiale del Mediterraneo occidentale,” in Ceramique Hellenistique et Romaines, ed. Jean-Paul Morel, Pierre Lévêque, and Évelyne Geny, vol. 3 (Paris, 2001), 177–275. Andrew Wilson, “Urban Production in the Roman World: The View from North Africa,” Papers of the British School at Rome 70 (2002), 231–73. Elizabeth Fentress et al., “Accounting for ARS: Fineware and Sites in Sicily and Africa,” in Side-by-Side Survey: Comparative Regional Studies in the Mediterranean World, ed. Susan Alcock and John F. Cherry (Oxford, 2004), 147–62. Michael Mackensen, “The Study of 3 Rd Century African Red Slip Ware Based on the Evidence from Tunisia,” in Old Pottery in a New Century. Innovating Perspectives on Roman Pottery Studies, ed. Danielle Malfitana, Jeroen Poblome, and John Lund (Catalina, 2004), 105–24. Michel Bonifay, “Observations sur la diffusion des céramiques africaines en Méditerranée Orientale durant l’antiquité tardive,” in Mélanges Jean-Pierre Sodini, ed. François Baratte (Paris, 2005), 565–81. Bes and Poblome, “African Red Slip Ware on the Move: The Effect of Bonifay’s Etudes for the Roman East,” in Studies in Roman Pottery of the Provinces of Africa Proconsularis and Byzacena (Tunisia).

- See Daniel Hoyer, “Public Feasting, Elite Competition, and the Market Economy of Roman North Africa,” The Journal of North African Studies 18/4 (2013), 574–91 for a discussion of the role of local, urban elite in Africa’s economic development in the imperial period.

- Dietz, Senatus contra principem, pp. 333–4 notes, with some surprise, that most of the senators and other ruling elite who chose to rebel against Maximinus in AD 238 came from families who had received favor from, and thus remained loyal to, the Severan rulers, including the Gordiani. I am not discounting the socio-political importance of loyalty to a ruling dynasty. Rather, I am arguing here that part of the benefits that these elite Roman families received from the Severans, especially those living in Africa, and therefore part of the reason they would remain loyal to Severan supporters, was the income they gained from the region’s flourishing economy.