It was a catalyst for economic growth in what otherwise remained a somewhat stagnant agricultural economy.

By Dr. John Oldland

Professor Emeritus

Williams School of Business

Bishop’s University

Introduction

Employment in clothmaking, and its economic value, impact and importance has been significantly underestimated by those historians who have briefly considered it.1 Demand for woollen cloth rose after 1400 as domestic consumption grew; and dramatically increased after the mid fifteenth-century recession as both domestic demand and exports rapidly expanded.2 After 1475 clothmaking had a significant impact on the economy, and especially rural household incomes in southern England. Rural clothiers became so efficient that nearly all production, except for some of the finest cloth, and some finishing, moved away from larger towns. Production of quality broadcloth came to be concentrated in southern England, cheaper narrow cloth pushed to the far west and north where costs were lower, and almost all cloth was exported through London. This chapter will suggest that there were perhaps 264,000 people making woollen cloth by the mid sixteenth century, or about 18 per cent of the adult population in 1540; and secondly that the amount of cloth produced in 1540 was maybe six times that woven in 1300, even though population had been reduced by perhaps a half.3

Economic impact was far greater than even these figures suggest. Much of the cloth made in 1300 was homespun that produced no income: in 1550 a far greater percentage was commercially woven with spinsters and weavers paid in ready money. Wool and cloth production, its trade and the jobs it created, seem to have been the key driver in the geographical redistribution of wealth to the southern half of the country from the fourteenth to the mid sixteenth century. The cloth industry after 1475 was a catalyst for economic growth in what otherwise remained a somewhat stagnant agricultural economy.

Changes in Product and Process

The English cloth industry became increasingly competitive because its merchants and clothiers were able to both raise quality and lower production costs. Not only did the product change dramatically, but broadcloth prices came down as wool prices fell after 1380, process technology improved, and clothiers made the production system more efficient. In 1300 the industry was in the process of changing from worsteds to woollens; in 1550 almost everyone wore woollens.4 Worsteds in 1300 could be easily made in village homes, and most were. The wools used were of average length and available locally. They were combed and spun with distaff and spindle in their natural oils and woven by one person on a narrow loom, and most of the cloth was around a foot in width, and woven in short lengths of ten feet or less. The cloth did not need to be fulled, or finished.

In 1550 almost all woollen cloth was heavily fulled woollens, mostly woven on a broadloom which was a much lengthier and more complex process. The wool used was shorter and curlier and therefore may have had to be purchased from wool broggers. The wool was sorted, washed and then greased with oil. The warp was combed and rock-spun, the weft carded and wheel-spun. Commercially produced cloth was usually woven on a broadloom that cost three or four times more than a narrow loom. Cloth was usually woven to a width of two and three-quarter yards wide on the loom, usually twelve to thirteen feet long after fulling in 1400, but twenty-four to twenty-six feet long in 1500, and sometimes as long as forty yards.5 The standard broadcloth now required 84lb of wool.6 To be efficient a weaver needed at least two looms, one of which was being prepared with the warp threads set, while two weavers sat side by side weaving cloth on the other. The cloth had then to be degreased, other impurities removed and fulled at the fulling mill.7 The fulled cloth was re-stretched on a tenter and wet sheared before delivery to a shearmen who would lightly grease the cloth, nap and shear it several times, and then fold and pack the cloth. In the early fourteenth century there was also an intermediate product, serge, using worsted warps and woollen wefts, and lightly fulled. We can see the process of transition from worsteds to woollens through the growth of fulling mills catalogued by Carus-Wilson, Langdon and others.8 The transition from worsteds to woollens was almost complete by 1350. Clothmaking had become more labour intensive, and it was far more difficult for a household to make cloth of acceptable quality in 1550 than 1300.

Woollen cloth became steadily heavier. Worsteds were not only easier to produce, but were also lighter, and therefore used less wool. I have estimated that the weight of cloth based on the size of standard broadcloth went from 38lb at the beginning of the fourteenth century to 64lb in the mid sixteenth century, an increase of 70 per cent.9 This weight increase was not just because of the transition to woollens, but also the desire for higher quality cloth as the standard of living rose; and because English merchants forced up the weight of exported cloth as wool prices went down in the fifteenth century. The fixed wool subsidy on the declining price of English wool exports made wool increasingly more expensive for continental draperies. The more English wool used to make broadcloth the greater the English price and value advantage.

Woollens production became more efficient as technology improved. Mill fulling replaced foot fulling, and mills became more efficient. Weft thread became wheel spun in the fourteenth century, and warp thread for coarse cloth started to be wheel spun in the later fifteenth century.10 The fulling mill produced a 70 per cent cost saving over foot fulling, and wheel spinning a threefold productivity improvement for spinning weft.11 The gig-mill mill that mechanized raising the nap, part of the finishing process, was used in mid fifteenth-century Wiltshire, but was prohibited by parliament in the mid sixteenth century.12

More important than technology was the rural clothier, who used capital and labour more effectively. He had sufficient capital to control the complete production process, in contrast with urban drapers who mostly financed trade, but tended to ignore production until the cloth was fulled: only investing in finishing and dyeing-in-the-piece. The clothier bought and often dyed the wool, financed its production, invested in looms and fulling mills, built up wool, yarn and cloth inventories, and financed its sale. The clothier used labour more efficiently. He paid piece rates, used female and child labour extensively, and adjusted his use of labour to blend with the rhythms of agricultural life.13 For example, the Kendrick Newbury workhouse accounts from the early seventeenth century show us that little yarn was spun in late August and early September, as spinsters went to the fields.14 From 1562 justices of the peace could force artificers to bring in the harvest.15 The clothier specialized in one type of cloth for which he found a national market, rather than produce a range of cloths, typical of most urban draperies, to suit a broad but limited regional market. By the sixteenth century standard broadcloth was woven in East Anglia and the West Country; kersey across southern England; cheap narrow cloths in Devon and Cornwall, Wales, Cheshire and Lancashire. The West Riding made inexpensive dozens and kerseys. Only the highest quality ‘long cloths’ were made in towns: Worcester, close to the finest wools, made whites, and Reading and the Kentish Weald, near London, specialized in finished, coloured cloth.

Size of the Industry

Historians have tended to underestimate the size of the industry, and therefore conclude that it had limited economic impact. Michael Postan in 1950 stated that ‘the numbers engaged in English cloth production at its height could not possibly have accounted for more than an insignificant proportion of the rural population in the country’. He thought demand was less than 50,000 cloths, which produced 15,000 full-time jobs, equivalent to 0.65 per cent of employment in 1377.16 He estimated that the wage to make a broadcloth at the beginning of the fifteenth century was thirty shillings, and that it took fifteen weeks work to make a cloth, earning 24d a week. Eleanora Carus-Wilson pointed out that this underestimated the number of workers because yarn preparation was lower paid work.17

Carus-Wilson in the same year correctly estimated that 17,000–20,000 more clothworkers were producing exported cloth at the end of the fourteenth century, based on full-time work. Assuming that no woollen cloth was imported and that domestic demand was static, there were 23,000–26,000 more clothworkers at the end of the century than at the beginning.18 She acknowledged that more workers were involved because some of the work was part time. Richard Britnell, writing in 1997, believed that the increase in cloth exports from the 1450s to the early 1540s may have created employment for around 21,500 people.19 He estimated that the hours taken to produce broadcloth was equivalent to a quarter of a year’s work. Since this full-time work was only equivalent to the labour of 1.2 per cent of the population aged sixteen years or over, it was unlikely to have much effect on economic growth. It should be noted that all three used the concept of full-time work. Britnell defined it as 270 working days a year.

If you add the figures of these eminent economic historians together, combining Postan’s domestic market figures with Carus-Wilson and Britnell’s figures for the export market, the total is still only around 61,000 jobs devoted to clothmaking in 1540 assuming a static domestic market of 50,000 cloths, hardly a vital economic force. Both Carus-Wilson and Britnell thought that the domestic market, at best, was stagnant, so all economic growth was in exports, and this produced around at best 46,000 jobs. Not insignificant since the population halved, but insufficient to move the economic needle.

The size of the domestic cloth market was far greater than Michael Postan and the wool historians Robert Trow-Smith and Peter Bowden thought when they considered the subject in the 1950s.20 It was always greater than the export market, rather than a small percentage of it, even when exports surged in the early sixteenth century. Edward Miller thought that home demand in the early fourteenth century might have been equal to 150,000 to 200,000 broadcloths.21 Christopher Dyer suggested that, if in 1500 1,250,000 adults were buying three yards of cloth annually, this would amount to 160,000 cloths, double cloth exports.22 Looking at the number of weavers and their likely production in the Babergh Hundred, Suffolk in 1522, where the county’s clothmaking was concentrated, and then projecting this nationally, he felt that cloth production cannot have been any less than 200,000 cloths.23 In addition, there was considerable non-clothing usage for woollen cloth, which in 1688 was estimated to have been a third of clothing usage.24

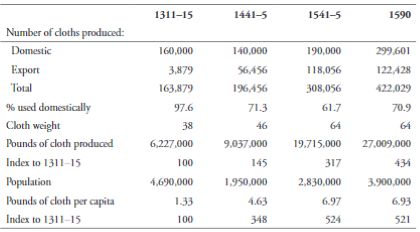

The estimates in Table 12.1 are based on domestic consumption of 160,000 cloths in 1311–15, falling to 140,000 cloths in 1441–5, and then rising quite dramatically through to the end of the sixteenth century. Per capita consumption rose dramatically after the Black Death through to the mid sixteenth century, and then continued to increase at a far slower rate until the end of the century, as the standard of living fell for the wage earner. Recent estimates suggest that pasture moved from 51 per cent of agricultural output in 1350 to 62 per cent in 1450.25 It is difficult to imagine that the per capita production of wool therefore went down anywhere to the extent that population declined, even taking into account that some of the pasture was used for cattle, and wool yields declined.26 Since wool exports fell far faster than the wool used in cloth exports from 1350 to 1450, the only conclusion must be that domestic consumption rose quite dramatically. Domestic consumption was driven higher by rising household incomes, colder winters, increasing weight of woollen cloth, improved productivity, and the allure of fashion. It is possible that by the mid sixteenth century the production of woollen cloth in terms of its total weight had risen almost six-fold from 1300. Craig Muldrew has recently estimated the domestic market to have been 300,000 cloths in 1590, with per capita consumption continuing to grow. I also believe that the customs figures for exports underestimated the size of the export market, because they excluded cheap narrow cloths that were not subject to petty custom, and cloth was actually longer than the standard cloth on which the figures were based.27 The figures in Table 12.1 tell us that cloth production per capita increased 3.5 fold from the 1310s to the early 1440s and then a further 50 per cent again over the next century.

Days Worked and the Number of Clothworkers

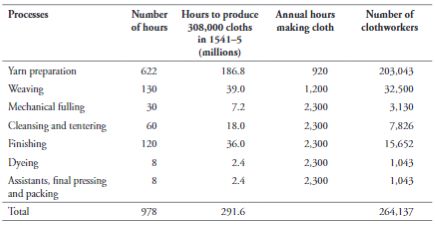

It took around 264,000 clothworkers, or about 15–16 per cent of the adult workforce, to make 308,000 equivalent broadcloths in the early 1540s.28 To reach this conclusion it is necessary to estimate how many hours each process took and how many hours, on average, a clothworker worked during the year. Broadcloth production was labour intensive. Quality mechanically fulled, late sixteenth-century broadcloth is estimated to have taken 978 hours to produce.29 Lord Cobham pointed out in the late 1560s that ‘the making of a broadcloth consisteth not in the travail of one or two persons, but in a number as of thirty or forty persons at the least, of men, women and children’.30 When Lord Kenyon investigated the establishment of a textile industry in 1588, his consultant Ralph Mathew considered that it would take sixty people to turn out either two broadcloths or six kerseys a week in Yorkshire.31 At Newbury in 1631–2 it took forty to fifty spinners to keep four broadlooms and one narrow loom going, and this necessitated the establishment of four spinning houses in the countryside apart from spinners in Newbury. Every two weeks someone visited the houses to distribute wool to spinners and pick up yarn.32

To put this labour intensity in perspective, a shepherd looking after 400 sheep could produce wool for ten cloths. The 978 hours to produce broadcloth was just under half a year’s work, so it would have taken close to five clothworkers to use all the wool the shepherd produced. Sixty-four per cent of the hours involved in making cloth were mostly secondary employment by country women and children sorting, combing and spinning wool. Weaving a cloth took 130 hours, and some of this must have been part-time, as women and children would have frequently set up the looms and wives sat side-by-side weaving with their husbands. Most were employed in the countryside, a higher percentage than a century before. Admittedly the estimate, that the average cloth took 978 hours to make, is a little high. Much exported cloth was dyed and finished at Antwerp at this time, and not all cloth was pressed and properly packed. On the other hand there was additional work moving the cloth, negotiating with suppliers, etc.33 Also, the average cloth probably took less time than high quality broadcloth. Cheaper cloth used cheaper processes, and cloths like cottons and frieze were less expensively finished. Yet most cloths were surprisingly similar in weight per area, and those that were slightly lighter were offset by the finest long cloths made in places like the Kentish Weald that took longer to make.34

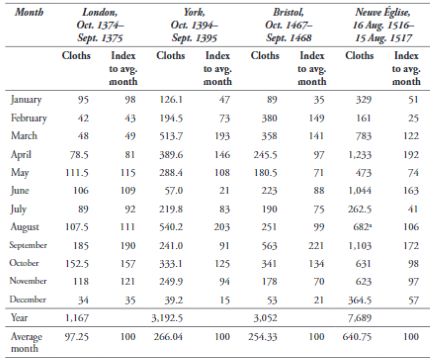

The estimate of the time worked, 2,300 hours for full-time work (230 ten-hour days) fulling, and finishing cloth, 1,200 for part-time weaving, and 920 hours for yarn production, is speculative. There continued to be considerable under-employment after the Black Death as many found it easier to sustain an acceptable standard of living with less work. An analysis of late sixteenth-century weaving showed that the average weaver worked at only half his capacity.35 There are records of daily presentations of cloth to the alnager in three English towns, London, York and Bristol, and these can be compared with a Flemish town, Neuve Église (Table 12.3). In London, in 1374–5, records demonstrated the seasonality for fulling cloth, since it was usually fullers who presented cloth to the alnager and then sold it to merchants.36 At York it was weavers presenting cloth in 1394–5, among them 105 women bringing small amounts of cloth, some as little as three yards in length.37 At Bristol in 1467–8 we see clothmakers often bringing one or two cloths to the alnager each day, rather than assembling large quantities before presentation.38 Production in the highest months might be four times that of winter months when days were shorter. December and January were particularly low production months, June and July tended to be soft, September and October were peak months.

There are two studies on work hours in England that bracket the 1540s, one in 1433 for lead-workers in the Mendips and the other for 1560–9.39 For 1433 Ian Blanchard concludes that the miner/farmer spent around half the year, 135 days, farming his five acres of leased land, and around a further sixty-five days mining for a total of 200 days.40 Blanchard’s farmer-miner worked only as long as it took to sustain himself, his mining income roughly equivalent to his rent and the need to maintain his capital equipment. An Antwerp study for the mid fifteenth century concluded that building workers worked for an average of 210 days a year.41 By 1560–99 the number of days agricultural labourers worked had risen to 257.42 The literature on work psychology seems to support the proposition that the pre-industrial wage labourer was motivated by need rather than greed, that increases in days worked, as in the later sixteenth century when real wage rates were declining, was driven by the need to work harder to sustain an accustomed standard of living.43 Allen and Weisdorf concluded that ‘“industrious” revolutions did indeed occur among farm labourers. However, these appear to have come out of economic hardship with no signs that they were associated with consumer revolutions’. This conclusion may not hold for the late medieval period. Allen and Weisdorf ’s calculations show that it took half the number of days to earn the money to buy a basket of basic consumption goods in 1450 than 1350.44 The inference, although not expressly stated, is that the labourer worked less. He simply concluded that ‘it implies idle labour in the countryside in the fifteenth century’.45 However, there is plenty of evidence that the basket of consumables changed: families ate more meat, purchased more clothes, bought more small luxuries, for example. It seems quite logical that many people worked the same number of hours, and maybe more, to adjust to a rapidly changing range of consumer wants: that a taste of a better life was a considerable inducement to work harder, and they then had to work harder again when real incomes began to fall in the sixteenth century. It may have been that after 1470, when rising living standards plateaued but the range of low-cost luxury goods available to buy continued to expand, labourers worked harder. In 1536 forty-nine holy days were removed from the calendar, which also led to some increase in the number of days worked.

For this exercise it is assumed that clothworkers worked 230 days a year because, especially from the mid fifteenth century onwards, they were more entrepreneurial, ambitious and acquisitive than Blanchard’s lead miners.46 Tenant farmers were forced to work harder to pay rents and tithes when agricultural prices were falling, or they would lose money.47 In a period of rapidly rising demand for cloth there was greater opportunity to work harder, demand forcing supply. Further, clothworking was a year-round activity, whereas lead mining was possible only from March to October; the work was easier and certainly closer to hand. Since the Mendips was also an important clothmaking region, perhaps the more ambitious became clothmakers. Real wage rates for labourers were declining from the 1520s providing an inducement to work harder.48 The assumption is that most yarn preparation was by married women who gave about 40 per cent of their time to clothmaking, based on a late seventeenth-century study showing that married women spun 2.5lb of wool a week, and single women 6lb.49

Clothworkers’ Wages

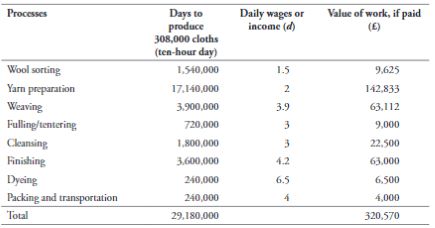

It is estimated that wages from producing 308,000 cloths in 1540 would have amounted to £320,570, if all the cloth was produced with paid work; equivalent to just over one pound a cloth (Table 12.4). There are no detailed English cloth production accounts: nevertheless, there is sufficient wage data to roughly estimate the fifteenth-century labour cost to produce broadcloth. Much clothmaking was set on the basis of piece rates, payment for work done. Consequently work was accomplished with reasonable efficiency, and clothiers aggressively competed on both price and quality.50 Further, there seems to have been a working convention at the time that the master weaver received two thirds of the value of the work, and the servant a third.51 So the price of weaving in effect has the lower wages for wives, children, servants and apprentices built into the cost. The average daily wage for making cloth was 2.64d because so much work was by women and children. For comparison, Bowden’s estimate for the average agricultural labourer outside harvest time in southern England was 4.66d; and Phelps Brown and Hopkins’s for southern craftsman in the 1532–48 period was 6–7d.52 Clark’s more recent estimate combining agricultural day wages and piece-rate wages for 1540–9 was lower at 3.63d.53

Thorold Rogers observed that artisans’ piece work tended to pay less than daily work before the fifteenth century, and a little more afterwards.54 Blanchard’s miners saw their daily rates increase between 1430 and 1460 from 3d to 4d per day.55 Although we have no wage price series for clothworkers their rates also may have increased as demand for their services rose, and clothiers competed for reliable, expert spinners on whom they ultimately depended. This also seems to be supported by the dispersion during the fifteenth century of low-priced cloth production to peripheral areas of the country where spinning costs were lower.

One of the advantages of rural clothmaking was that children and wives could work without regulation, whereas urban guilds excluded women from most organized trades with some few exceptions, silkweavers for example.56 In towns, women’s economic position seems to have deteriorated with the mid fifteenth-century depression, and did not recover as population slowly expanded.57 Rural women carded, spun and wove: boys carded, set up the loom, and may, on occasion, have woven. Combing the warp thread was harder work often done by men.58 Payment depended on the type and location of work. Combers, carders, spinners and weavers were paid piecework. Fullers charged by the cloth but either paid their labourers a daily wage or had servants under annual contract, and some labour was by women and boys.59 Shearmen charged by the cloth or yard, as did dyers, but they also paid their workers a daily wage, and employed servants and apprentices. Fullers and dyers had to include in their prices some estimate for the value of their considerable capital investment, raw material costs, and leases. The participation of women, children, servants and apprentices makes any estimate based on the wages of master craftsmen far too high, and rural wages were lower than urban wages.60 It was explained at York that the flight of its textile industry to the West Riding in 1561 was ‘not only the comodytie of the water mylnes is ther nigh at hande, but also the poore folke as speynners, carders, and other necessary work folks for the sayd webbing, may ther beside ther hand labor, have rye, fyre, and other relief good cheape, which is in this citie very deare and wantyng’.61

The price of women’s work has been set at 50 per cent of man’s work based on daily wage rates, 2d a day.62 There is evidence that women were paid equal to men after the Black Death if based on piece rates, if they could do the work; and around 70 per cent of men’s wages for agricultural work when paid on a time basis.63 This clearly did not apply to yarn preparation. Men were rarely involved, the work was year-round and it was usually secondary employment. In fact 2d a day was an excellent wage, if compared with men’s wage paid at the winter rate which might be 25–33 per cent less than the summer wage, or servants’ wages based on annual contract.64

The clothier would have sorted the wools, for weft and warp, scoured the wool and then oiled it. This must have been women’s work, but we have no cost information. As it was unskilled work, it is estimated to have been 1½d per day, compared with combing, carding and spinning at 2d per day.65 There are very few late medieval references to spinning cost. At Laleham in 1290, carding and spinning cost 2d/lb for weft and 3d/lb for warp.66 In the 1580s spinners were paid 2–3d per pound.67 If in the 1540s they were paid 2d, and they carded and spun 1lb a day, their daily wage would have been 2d, or 11d a week. Married women, servants and children in the household could earn an additional 1d daily for the family for five hours work. Hatcher has estimated that the average late fifteenth-century wage for servants was only 2¼–2½d given that they were paid lower wages during the year than at harvest time, and that there was considerable unemployment.68 In this context spinners were well paid, for their income was only just below a skilled worker’s agricultural wage, if spinning was continuous work.69 We have no way to determine the days worked by an average spinner. However, clothiers had the capital to maintain large wool and cloth inventories and they were operating in a rising market for cloth from 1450 to 1550, so they may well have been able to offer steady work. In 1472, the clothier William Spryng of Lavenham on his death had sixty cloths in inventory; in 1480 Robert Rychardes of Dursley, Gloucestershire, had in storage £18 of warp thread, £23 of weft thread, and twenty-two broadcloths, as well as another fifteen or so in London; the Salisbury weaver, William Cuff, in 1500, had £7 of wool, £8 6s 8d of yarn, seventy broadcloths, twenty-six kerseys and thirty-seven dozens in his house; and the Cranbrook clothier, Stephen Draner, in 1540 left £11 of wool and yarn, and cloth worth £174 10s in storage.70

Weavers and their assistants spent fifty hours to prepare the warp and weft thread and then warp the loom; and eighty hours to weave broadcloth. At Colchester in 1388 a low quality half-broadcloth cost 1.87d per yard to weave, if we assume it was sixteen yards on the loom, but better quality cloth cost 3d per yard.71 At York in 1400 journeymen weavers were allowed to charge 2.3d per yard for weaving fourteen yards.72 In 1502 in Norwich low quality broadcloth, thirteen yards in length cost 20d, 1.54d per yard.73 At Coventry low quality cloth cost 48d, medium quality, 54d and high quality 60d to weave, or assuming length on the loom of thirty-two yards, 1.5d per yard, 1.69d per yard and 1.875d yard respectively.74 The duke of Norfolk paid 2d a yard to weave thirty-seven yards of brown broadcloth in the 1460s.75 The prescribed price for weaving a quality broadcloth at York in 1505, thirty-five yards in length before fulling, was 2s 8d, or only 0.91d a yard.76 Weaving a cheap dozen in 1588 cost 2.25d per yard.77 If we assume that an average broadcloth, thirty-two yards on the loom, in the 1540s cost 1.75d per yard or 56d a cloth, and it took 14.4 nine-hour days to weave, then the cost per day would have been 3.9d. If we also assume that the assistant was paid half the master’s wage and they each did half the work, then it was equivalent to 4.9d a day for the master and 2.9d for the servant/wife.

It took an estimated thirty hours to full broadcloth, and sixty hours to wash and clean it. The only reference to the cost of fulling in the literature was at Chester in the 1390s when it cost 20d to mill-full a hundred yards, and 10d to tenter the same length of narrow cloth.78 This might be equivalent to one and a half broadcloths, so fulling broadcloth would then cost 13.3d. Mill fulling was capital but not labour intensive. Hypothetically, a servant supervising the process, paid 3d per day, would cost 8d, leaving a 5.3d profit for the master. Washing and cleaning the cloth required the work of a master and two assistants. If the master earned 6d and assistants 3d, then the average cost was 4d a day, and the cost for a cloth 24d.79 At Bristol in 1381 those working for fullers ‘on the land’ were paid 3d a day.80 The duke of Norfolk paid 36d to burl a blue cloth in the 1480s.81

The standard charge for finishing, combining the work of both the fuller and the shearmen to finish standard broadcloth at the end of the fifteenth century, was 2½d a yard.82 It cost Sir Thomas Howard in the late fifteenth century 48d to shear his broadcloth in Suffolk.83 In the 1520s it cost the London draper, Thomas Howell, 2½d per yard to have his cloths napped and sheared, 60d for a twenty-four yard cloth.84 If finishing a twenty-four yard broadcloth was 60d, and it took 14.4 days (130 hours over nine days), then the daily wage was 4.16d. If the work was done by one master fuller or shearman, and two assistants, and the master earned twice the servant’s wage, then the master earned 6d, and the servant 3d.

Master dyers were highly skilled and carried great responsibility. In 1563, when rates were set for all London journeymen at £6 13s 4d, an exception was made for dyers’ foreman who were to be paid £10, equivalent to 10d a day for a 230–day working year.85 Assuming in the 1540s that the average master dyer was paid 10d and his two assistants 3d, and the master did half the work, then the average daily wage was 6.5d.

It is interesting to note that the value of women’s work, if that was equated with wool sorting and yarn preparation, was 48 per cent of all work. It has been estimated that in the 1590s the earnings of a married woman, who spent half her time spinning, would have been equivalent to 31 per cent of a labourer’s wage.86

Economic Value

Rept0n1x, Wikimedia CommonsThe value of the cloth industry can be determined by multiplying the price of cloth by the number of cloths, but there are two problems, price inflation in the 1540s and the wide range of cloth prices. Price inflation, beginning in the 1520s, gathered momentum with Henry’s 1542 currency devaluation. The range of prices across a broad range of cloths is best illustrated by the large inventory of a Salisbury draper, David Lewis in 1548, whose sixty-nine rolls of quality broadcloths, ranging from 144d per yard for one scarlet to 24d per yard for coarse red and black cloth, produced an average of 53d yard or 1,272d (£5 6s) for a broadcloth: his sixteen northern dozens were valued at 23d yard.87 The price of his ten quality kerseys was 28.5d per yard, and his cheaper kerseys 19d per yard for an equivalent width of broadcloth.88 His eight straits were worth 26d per yard for equivalent broadcloth. The thirty-nine cheap narrow cottons, frieze and kendalls were worth 13d per yard for equivalent broadcloth width. If we assume that broadcloth was 50 per cent of the market, northern dozens 10 per cent, kerseys and straits 20 per cent, and cottons and frieze 20 per cent, then the average wholesale price for woollen cloth was £3 12s.89 Thorold Rogers’ prices for first quality Cambridge broadcloth indicate rapid inflation during this period, as it was purchased for 80s in 1536 (assuming a twenty-four yard cloth), 108s in 1541 and 130s 8¾d in 1544, and averaging 128s for the period 1544–9; second quality cloth was 66s 6d in 1536, 81s 4d in 1541; even third-quality cloth was 76s in 1541.90 In 1548 Cambridge coloured broadcloth was purchased for £6, a 15 per cent premium over David Lewis’s wholesale price.91 Using this markup the average price of retail cloth in 1548 is estimated to have been £4 2s 10d.

The assumption is that an average cloth was priced at retail at around £4 in the early 1540s, and that therefore production wages accounted for a quarter of the final price.92 If all cloth was traded on the open market, then the value of cloth production would have been around £1,232,000 or 11.2 per cent of net national income, estimated at £11 million in 1546.93 It has been estimated that industry was around 39 per cent of the economy in 1522, or £4.29 million, so woollens manufacture would have been 28.7 per cent of industrial output (including mining), again if all cloth was purchased on the open market.94 In 1700 woollens’ share of industry was 27 per cent.95

This industry value is exaggerated because homespun continued to be made in large quantities, and this was unpaid work, unless it was traded at fairs and markets which, in fact, must often have been the case. We can see, from the alnage accounts for York and Middlesex for 1394–5, women bringing very small lengths of cloth to pay the subsidy and then be sold.96 So we need to consider just how much cloth in 1300 and 1550 was homespun, and how much commercially produced. Unfortunately we cannot answer this question with statistics, but a far greater percentage of cloth was woven for the commercial market in 1500 than 1300. The growing complexity of the production process for woollens, increased capital, higher quality expectations and skill requirements all favoured commercial clothmaking.97 Further, after the Black Death, other occupational opportunities and increased specialization reduced underemployment levels, and this made it logical to buy rather than make cloth. It has been suggested that landlords, farming their own demesnes, who had previously arranged for turning wool into cloth for their household and retinues, were now buying it on the open market.98 But the crucial factor was the rural clothier whose capital, expertise and organization made cloth production so much more efficient that both homespun and urban clothmaking became uncompetitive. The growth of urban clothmaking in the second half of the fourteenth century was reversed in the fifteenth, before recovering in the second quarter of the sixteenth with the rising export of the highest quality long cloths.99

The narrow cloth clothier was a far smaller operator, making kerseys or straits. The area of cloth was a quarter to a third of the size of broadcloth, required only a narrow loom, and straits were sold on the basis of cost not quality and therefore required less skill. He might be independent but he often sold his cloth to a clothier to finish and market. In a sense he was the successor to the maker of homespun, but he was making cloth for a regional, national or international market. For instance, narrow cloths transformed the Devon economy as kerseys and straits were made in most of its villages and small towns in the early sixteenth century.100

There were still broad areas of the country where homespun was still widely woven, especially in central and northern England, whose economy remained depressed in the later fifteenth century, and were distant from the emerging areas of commercial rural clothmaking. In Woodward’s study of late sixteenth-century northern builders, he found that over a third of Lincolnshire carpenters’ inventories between 1550 and 1600 had spinning wheels, and more than 20 per cent among Lancashire and Cheshire carpenters between 1580 and 1660.101

Economic Impact

This study suggests that the demand for cloth was far greater than has been suggested. A recent study concluded that industry, which accounted for 19.2 per cent of the economy in 1381, had risen to 22.7 per cent in 1524.102 Bruce Campbell estimated that ‘non-agricultural employment may have contributed roughly a tenth of rural incomes by 1300. Two centuries later this proportion had probably doubled, as manufacturing fastened more vigorously onto rural labour’.103 Clothmaking was important because of its size and the employment it generated: woollens production was more labour intensive than worsteds, less homespun was woven, and demand for cloth increased both domestically and for export. At the same time technical and organizational change produced significant improvements in productivity. The industry became more geographically specialized as regional clothiers leveraged their competitive advantage, cheaper cloths moving to areas furthest from London in the later fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries.104

The rapid increase in textile income stimulated other work. One extra shepherd gave rise to as many as five clothmakers who eventually helped to create many more jobs. Some of the jobs were to supply the industry with raw materials and market the cloth, but most were to support other agricultural, manufacturing and service jobs that developed as income was spent. To give some obvious examples: the population of Coventry and York slumped once the cloth industry declined in the fifteenth century; and Lavenham, a sleepy village in 1400, was transformed into a prosperous cloth town, supporting seventeen non-textile trades in the 1520s.105

This chapter illustrates that household, rather than male employment is critical to our understanding of the late medieval rural economy. John Hatcher’s recent provocative paper on wages and living standards showed how difficult it was for a fifteenth-century tenant farmer with 18–20 acres to make a profit as prices fell faster than rents, and that this could not be achieved if he was paying harvest wages throughout the year.106 He undoubtedly improved his economic position by increasing the size of holdings and converting arable to pasture, lowering wage costs by hiring on annual contracts, using household labour more effectively, and employing other cost-reduction farming practices. He also increased his income through rents, and diversification into industry or services.107 In southern England clothmaking was the primary secondary employment opportunity.

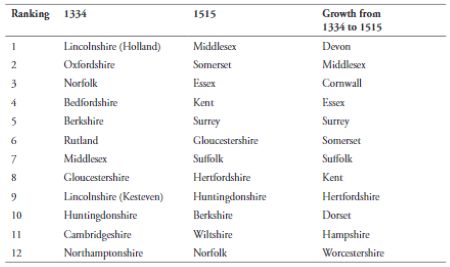

The dramatic economic impact of the cloth industry seems to be clear from Schofield’s comparative ranking of the wealth in the top twelve counties from 1334 to 1515 (see Table 12.5). London’s rapid growth in wealth spread to the counties that surrounded it – Middlesex, Surrey, Kent, Essex and Hertfordshire – and the most important factor in London’s growth was expansion in the value of its cloth trade, and the increased wealth from trade in imported merchandise that cloth now mostly financed.108 Clothmaking counties were among the wealthiest in 1515, and dominated the list of those counties with the most rapid growth from 1334.109 Much of the change probably occurred at the end of the period, after 1470. From the 1520s continued industry expansion provided an opportunity for additional employment that would offset the declining buying power of wages as inflation began to grip the country.

This chapter is also relevant to the work by Nick Mayhew, Gregory Clark, and the ‘National Income Group’, led by Stephen Broadberry, who are trying to track the long-term performance of the English economy. This is extremely difficult for the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries since the manorial database based on demesne agriculture becomes less reliable as a general indicator after 1420, and the early modern database based on probate inventories becomes available only in the second half of the sixteenth century.110 Further, estimates for population around 1300, and for 1379–81 and 1522 based on the poll tax and muster returns are subject to some error that may affect projections for changes in per capita income. Sectoral studies such as this can modify conclusions that come from macroeconomic studies. Clothmaking was important because it affected both the sheep population and secondary employment in the countryside, agriculture and industry. For example, the National Income Group projected sheep numbers falling from 15 million in 1300 to a trough of 11.29 million in 1400–9, only to rise to 9.55 million in 1550–9, then leaping to 16.75 million in 1600–9.111 My projections are 13.7 million adult sheep in 1311–15, falling to 11.4 million in 1391–5, rising to 12.8 million in 1491–5, and then dramatically increasing to 15.0 million in 1541–5.112

The national income study also projected that the value of textile production, indexed to 100 in 1700, was 42.01 in 1350, and fell to a low of 31.45 in 1500 before rebounding to 46.04 in 1550 and 66.10 in 1600.113 This chapter suggests that textile production, rather than following the general reduction in demand for most of the fifteenth century, was in fact a stimulus to the economy until the mid-century depression, and then a catalyst for economic recovery at the end of the century. Farmers struggled to sustain themselves as agricultural prices fell; while industrial work, often based on piece-work wages and secondary employment, became more efficient and productive, especially in the countryside. The national income study has per capita GDP declining annually by 0.07 per cent from the 1450s to 1480s, remaining stable until the mid sixteenth century, and then growing strongly at 0.17 per cent in the second half of the century.114 Higher textile employment and income, and its rippling effects throughout the economy, may well have resulted in higher per capita economic growth from 1475; with acceleration from the later fifteenth century, thus either bringing closer together the growth rates in the first half and second half of the sixteenth century, or even reversing the trend, with per capita growth rates in the first half of the century exceeding those in the second.

Endnotes

- M. Postan, ‘Some economic evidence of declining population in the later middle ages’, Economic History Review, 2nd ser., iii (1950), 221–46, at p. 232; E. M. Carus-Wilson, ‘Trends in the export of English woollens in the fourteenth century’, in E. M. Carus-Wilson, Medieval Merchant Venturers: Collected Studies (1967), pp. 239–64, at pp. 261–2; R. H. Britnell, ‘The English economy and the government, 1450–1550’, in The End of the Middle Ages? England in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries, ed. J. L. Watts (Stroud, 1998), pp. 89–116, at p. 93.

- J. Oldland, ‘Wool and cloth production in late medieval and early Tudor England’, Economic History Review, lxvii (2014), 25–47, at p. 29.

- There still is no consensus about the population in 1300 and the depth of its decline by the mid 15th century, so the extent of population change from 1300 to 1550 is debatable.

- J. Munro, ‘Textile technology’, in The Dictionary of the Middle Ages, Volume 11, ed. J. R. Streafer and others(New York, 1988), pp. 693–711, at p. 694.

- Records of the City of Norwich, ed. W. Hudson and J. C. Tingay (2 vols., Norwich, 1901), ii. 105–6; York Civic Records, Volume III, 1504–1536, ed. A. Raine (York Archaeological Record Series, cvi, 1942),p. 21; J. Oldland, ‘The variety and quality of English woollen cloth exported in the late middle ages’, Journal of European Economic History, xxxix (2011), 215–29.

- Tudor Economic Documents, ed. R. H. Tawney and E. Power (3 vols., 1924), i. 178–84.

- J. Langdon, Mills in the Medieval Economy: England 1300–1540 (Oxford, 2004), p. 46. The number of industrial mills is estimated to have risen from 600 in 1300 to between 1,300 and 2,000 in 1540.

- E. M. Carus-Wilson, ‘An industrial revolution of the thirteenth century’, in Carus-Wilson, Medieval Merchant Venturers, pp. 183–210; R. Holt, The Mills of Medieval England (Oxford, 1988), p. 154; Langdon, Mills, pp. 40–63.

- Oldland, ‘Wool and cloth production’, p. 29.

- Hudson and Tingay, Records of the City of Norwich, ii. 105–6; H. Lemon, ‘The development of hand spinning wheels’, Textile History, i (1975), 83–91, at pp. 87–8; J. Munro, ‘Medieval woollens: textiles, technology and industrial organisation, c.800–1500’, in The Cambridge History of Western Textiles, ed. D. Jenkins (Cambridge, 2003), pp. 197–202; P. Chorley, ‘The evolution of the woollen, 1300–1700’, in The New Draperies in the Low Countries and England, 1300–1800, ed. N. Harte (Oxford, 1997), pp. 7–34, at p. 22. The first direct reference we have to an all-carded English woollen was at Norwich in 1508, where woollen weavers’ ordinances declared that low thread-count narrow cloths (350 warp threads per yard) were all wheel spun.

- Munro, ‘Textile technology’, p. 698; Munro, ‘Medieval woollens: textiles’, pp. 203, 207. The Saxony wheel introduced in the 15th century was twice as productive as the old wheel.

- Statutes of the Realm, 5&6 Edward VI, c. 22; E. M. Carus-Wilson, ‘Evidences of industrial growth on some fifteenth-century manors’, Economic History Review, 2nd ser., xii (1959–60), 190–205, at p. 201.

- J. Thirsk, ‘Industries in the countryside’, in Essays in the Economic and Social History of Tudor and Stuart England, ed. F. J. Fisher (Cambridge, 1961), pp. 70–88.

- Newbury Kendrick Workhouse Records 1627–1641, ed. C. Jackson (Berkshire Record Society, viii, 2004), p. xxix.

- Statutes of the Realm,4 Eliz. c. 4.

- Postan, ‘Some economic evidence’, p. 234.

- Carus-Wilson, ‘Export’, p. 261.

- Carus-Wilson, ‘Export’, p. 261.

- Britnell, ‘English economy’, pp. 92–3.

- Postan, ‘Some economic evidence’, p. 234; R. Trow-Smith, A History of British Livestock Husbandry (1957), p. 140; P. J. Bowden, The Wool Trade in Tudor and Stuart England (1962), p. 38.

- E. Miller and J. Hatcher, Medieval England: Towns, Commerce and Crafts (1995), p. 126.

- C. Dyer, The Age of Transition (Oxford, 2005), p. 159.

- Dyer, The Age of Transition, pp. 148–9.

- C. Muldrew, ‘“Th’ancient distaff” and “whirling spindle”: measuring the contribution of spinning to household earnings and the national economy in England, 1550–1770’, Economic History Review, lxv (2012), 498–526, at p. 514.

- S. Broadberry, B. Campbell, A. Klein, M. Overton and B. van Leeuwen, ‘British economic growth, 1270–1870: an output-based approach’ (2011), p. 34, <http://www2.lse.ac.uk/economicHistory/whosWho/profiles/sbroadberry.aspx>; charted in S. Broadberry, B. Campbell, A. Klein, M. Overton and B. van Leeuwen, British Economic Growth, 1270–1870 (Cambridge, 2015), p. 114.

- Oldland, ‘Wool and cloth production’, pp. 38–41.

- Oldland, ‘Wool and cloth production’, p. 43.

- This assumes adult population to be 60% of the total. In 1679 a pamphleteer estimated that 700,000 were connected with, or dependant on, the woollen industry (see A. P. Usher, The Industrial History of England (New York, 1920), p. 208).

- W. Endrei, ‘Manufacturing a piece of woollen cloth in medieval Flanders: how many work hours?’, in Textiles of the Low Countries in European Economic History, ed. E. Aerts and J. Munro (Leuven, 1990), pp. 14–33.

- BL, Cotton MS, Vesp. F., xii, fo. 168.

- Manuscripts of Lord Kenyon, Historical Manuscripts Commission, 14th Report, Appendix Part IV (1894), pp. 572–3, reprinted in Tawney and Power, Tudor Economic Documents,i. 216–17.

- Jackson, Newbury Kendrick Workhouse Records, pp. xxxiii–xxxv.

- In 1588, six out of the 60 people needed to produce broadcloth were just helpers.

- Statutes of the Realm, 5&6 Edward VI, c.6.

- W. Endrei, ‘The productivity of weaving in late medieval Flanders’, in Cloth and Clothing in Medieval Europe, ed. N. B. Harte and K. G. Ponting (1967), pp. 108–19, at p. 118.

- J. Oldland, ‘London Clothmaking c.1270–1550’ (unpublished University of London PhD thesis, 2003), pp. 84–6.

- The Early Yorkshire Woollen Trade, ed. J. Lister (Yorkshire Archaeological Society, xliv, 1925), pp. 47–95.

- PRO: TNA, E 101/339/11.

- I. Blanchard, ‘Labour productivity and work psychology in the English mining industry, 1400–1600’, Economic History Review, 2nd ser., xxxi (1978), 1–24; G. Clark and Y. Van der Werf, ‘Work in progress? The industrious revolution’, Journal of Economic History, lviii (1998), 830–43.

- The 65 days of mining for the mid 15th century is not explicitly stated by Blanchard, and has to be teased out of his text and charts. My estimate differs from Allen and Weisdorf ’s reading of Blanchard’s data, at 165 days a year in 1433 and 180 days in 1536 (see R. C. Allen and J. L. Weisdorf, ‘Was there an “industrious revolution” before the industrial revolution? An empirical exercise for England, c.1300–1830’, Economic Historical Review, lxiv (2011), 715–29, at pp. 720–1). My calculation for 1433 is based on reading the text, Table B1, and Figures 6(i) and 12 that is based on farmer-miners. Allen and Weisdorf use Table C2, Appendix C, based on all miners; farmer-miners, cottar-miners and professional miners. No estimate for working days for farmer-miners is possible for the 16th century because the mining population seems to have changed from farmer-miners to professional miners. The employment figures on Table C2 do not agree with those on Table B1–1 and Table B1–2, so there is no way of knowing the occupational characteristics of the 16th-century mining population from the article. It should be noted that Blanchard’s analysis for 1433 is centred around a sample of only 15 farmer-miners, which is presumably why he hesitated to draw firm conclusions on days worked.

- H. Van der Wee, The Growth of the Antwerp and the European Economy (3 vols., The Hague, 1963), i. Appendix 48, pp. 540–1.

- Clark and Van der Werf, ‘Work in progress?’, p. 838.

- L. Angeles, ‘GDP per capita or real wages? Making sense of conflicting views on pre-industrial Europe’, Explorations in Economic History, xlv (2008), 147–83; Allen and Weisdorf, ‘Was there an “industrious revolution”’, pp. 715–29.

- Allen and Weisdorf, ‘Was there an “industrious revolution”’, p. 719.

- Allen and Weisdorf, ‘Was there an “industrious revolution”’, p. 722.

- F. E. Baldwin, Sumptuary Legislation and Personal Regulation in England (Baltimore, Md., 1926); Dyer, Age of Transition, pp. 132–5, 143–7; C. Dyer, ‘Luxury goods in medieval England’, in Commercial Activity, Markets, and Entrepreneurs in the Middle Ages, ed. B. Dodds and C. D. Liddy (Woodbridge, 2011), pp. 217–38; Oldland, ‘Wool and cloth production’, pp. 35–7; J. Oldland, ‘London’s trade in the time of Richard III’, The Ricardian, xxiii (2013), 21–9.

- J. Hatcher, ‘Unreal wages: long-run living standards and the ‘golden age’ of the fifteenth century’, in Commercial Activity, Markets and Entrepreneurs in the Middle Ages, ed. B. Dodds and C. D. Liddy (Woodbridge, 2011), pp. 1–24.

- Allen and Weisdorf, ‘Was there an “industrious revolution”’, p. 719.

- Muldrew, ‘“Th’ancient distaff” and “whirling spindle”’, pp. 499, 507.

- R. C. Allen, ‘Progress and poverty in early modern Europe’, Economic History Review, lvi (2003), 403–43, at p. 413. Allen has worked out an index for productivity in making broadcloth, dividing the price of cloth by a geometric average of the price of wool and artisan wage rates. This shows some increase in productivity from 1500 to 1550. However, given the high amount of female labour in making cloth, artisan wage rates may not be a good proxy for clothworkers’ wages.

- The Coventry Leet Book, ed. M. Dormer Harris (Early English Text Society, Original Ser., cxxxiv, 1907), p. 94.

- E. H. Phelps Brown and S. V. Hopkins, ‘Seven centuries of building wages’, Economica, new ser., xxii (1955), 195–206, at p. 205; P. Bowden, ‘Statistical appendix’, in The Agrarian History of England and Wales, Volume IV 1500–1640, ed. J. Thirsk (Cambridge, 1967), pp. 864–5.

- G. Clark, ‘The long march of history: farm wages, population, and economic growth, England 1209–1869’, Economic History Review, lx (2007), 100.

- J. E. Thorold Rogers, Six Centuries of Work and Wages (1903), p. 328.

- Blanchard, ‘Labour productivity’, p. 21.

- P. J. P. Goldberg, Women, Work, and the Life-Cycle in a Medieval Economy: Women and Work in Yorkshire c.1300–1520 (Oxford, 1992), pp. 88–92.

- The Little Red Book of Bristol, ed. F. B. Bickley (2 vols., 1900), ii. 127–9; P. J. P. Goldberg, ‘Female labour, service and marriage in the late medieval urban north’, Northern History, xxii (1986), 18–38, at p. 35.

- Muldrew, ‘“Th’ancient distaff” and “whirling spindle”’, p. 503.

- Bickley, The Little Red Book of Bristol, ii. 10–14.

- Allen and Weisdorf, ‘Was there an “industrious revolution”’, p. 717.

- H. Heaton, The Yorkshire Woollen and Worsted Industries (Oxford, 1965), pp. 54–5.

- Wages for unmarried women were still estimated to be 50% of those of men in 1851 (see Clark and Van der Werf, ‘Work in progress?’, p. 840).

- S. Bardsley, ‘Women’s work reconsidered: gender and wage differentiation in late medieval England’, Past & Present, clxv (1999), 3–29; J. Hatcher, ‘Women’s work reconsidered: gender and wage differentiation in late medieval England’, Past & Present clxxiii (2001), 191–8, at pp. 192–3.

- The lower winter wage was for building craftsmen, see J. Munro, ‘Urban wage structures in late-medieval England and the Low Countries: work time and seasonal wages’, in Labour and Leisure in Historical Perspective. Papers presented at the 11th International Economic History Congress, ed. I. Blanchard(Milan, 1994), pp. 65–78, at p. 67.

- Before the Black Death, in Bristol Fullers’ ordinances, those raising the nap were paid 4d/day, those tramping cloth 6d/day and women ‘wedesteres’ were paid 1d/day (see Bickley, The Little Red Book of Bristol, ii. 10–16).

- T. H. Lloyd, ‘Some costs of cloth manufacturing in thirteenth-century England’, Textile History, i (1968–70), 233–6, at p. 235.

- Muldrew, ‘“Th’ancient distaff” and “whirling spindle”’, p. 504; M. Zell, Industry in the Countryside: Wealden Society in the Sixteenth Century (Cambridge, 1995), p. 167.

- Hatcher, ‘Unreal wages’, p. 6.

- Hatcher, ‘Unreal wages’, p. 14.

- TNA: PRO, PROB 2/7, 57, 174, 525.

- R. H. Britnell, Growth and Decline in Colchester, 1350–1500 (Cambridge, 1986), pp. 60–1.

- Heaton, The Yorkshire Woollen and Worsted Industries, p. 39.

- Hudson and Tingay, Records of the City of Norwich, ii. 105–6. The cloth had 700 warps per yard. The rates for higher quality cloth had to be negotiated.

- The Coventry Leet Book, ed. M. Dormer Harris (Early English Text Society, Original Ser., cxxxvi, 1909), p. 660. Warp counts for low quality cloth was 800–900; medium 900–1,000; fine 1,000–1,100.

- The Household Books of John Howard, Duke of Norfolk 1462–1471, 1481–1483, ed.A. Crawford (Stroud, 1992), p. 368.

- Raine, York Civic Records, iii. 21.

- Tawney and Power, Tudor Economic Documents, i. 217.

- J. Laughton, Life in a Late Medieval City, Chester 1275–1520 (Oxford, 2008),p. 143. At King’s College, Cambridge, in 1536 it cost 48d to aquatus and tonsus (full and shear) chorister’s cloth, which had cost 380d. If this included only the work done by a fuller (fulling, burling and tentering), then the average daily wage to complete the work would have been 5.7d/day (see J. E. Thorold Rogers, A History of Agriculture and Prices in England from the Year of the Oxford Parliament (1259) to the Commencement of the Continental War (1793) (8 vols., Oxford, 1866–1902), iii. 506). The wage would have been far less if it included dry shearing as well.

- At York burling (washing and cleaning) was 1d/yd, or 24d/cloth at the turn of the fifteenth century (see Heaton, The Yorkshire Woollen and Worsted Industries, p. 39).

- Bickley, The Little Red Book of Bristol, ii. 15–16.

- Hudson and Tingay, Records of the City of Norwich, ii. 407.

- This includes tentering the cloth, wet shearing it by the fuller, and the shearman raising and cutting the nap of the dry but oiled cloth. The fuller John Stoke and the shearmen Thomas Martyn had been paid 2½d per yard for finishing 339 yards of cloth for the bishop of London in 1477–8 and for two cloths in 1465–6, see TNA: PRO, SC 6/1140/26,27.

- B. McClanaghan, The Springs of Lavenham (Ipswich, 1924), p. 22.

- Drapers’ Hall, London, Thomas Howell ledger, fo. 17*.

- Tudor Proclamations, ed. P. L. Hughes and J. F. Larkin (3 vols., 1964), ii. 233, 256.

- Muldrew, ‘“Th’ancient distaff” and “whirling spindle”’, p. 510.

- TNA: PRO, E 154/2/22.

- Broadcloths were one and three quarters yards in width, kersey one yard and cottons and frieze three quarters of a yard.

- The composite price of £3.62 was 50% quality broadcloth at £5.30, 10% northern dozens at £2.30, 20% kerseys and straits at £2.40 for equivalent widths, and 20% cottons and frieze at £1.30 for equivalent widths.

- Thorold Rogers, A History of Agriculture and Prices, iii. 506–7; iv. 587.

- Thorold Rogers, A History of Agriculture and Prices, iii. 506.

- The reduction from £3.62 to £3.00 was made because of price inflation during the 1540s, and the belief that Lewis’s inventory would have been superior to the average price of cloth. The only long price series for woollen cloth gives prices for the 1540s of 42d a yard, or £4 5s 8d a cloth (see G. Clark, ‘The macroeconomic aggregates for England, 1209–2008’, Research in Economic History, xxvii (2010), 51–140, Table A1).

- Clark, ‘Macroeconomic aggregates’, Table 13. Mayhew has recently estimated national income to have been £8.62 million in 1546, based on the work by Broadberry and others, ‘British Economic Growth’, in which case woollens production would have been 14.3% of national income (see N. J. Mayhew, ‘Prices in England, 1170–1750’, Past & Present, ccxix (2013), 3–39, at p. 37).

- Broadberry and others, ‘British economic growth’, p. 38. In 1522 agriculture was estimated to be 39.7% of output, industry 38.7%, and services 21.6%.

- Broadberry and others, ‘British economic growth’, p. 35.

- Lister, The Early Yorkshire Woollen Trade, pp. 39–45; TNA: PRO, E 101/340/26, /27.

- For example clothiers often had several broadlooms: Robert Rychardes had three in his house in 1480; the Newbury weaver Nicholas Frere had two osette and two ‘quelyng’ looms in 1495; William Cuff in his weaving house in 1500 had three broadlooms and two other looms; John Scoten of Nayland in 1539 had three broadlooms in his weaving shop (see TNA: PRO, PROB 2/57, 95, 174, 233).

- A. R. Bridbury, Medieval English Clothmaking (1982), p. 64.

- Oldland, ‘Variety and quality’, pp. 227–8.

- C. Dyer, ‘Small towns 1270–1540’, in The Cambridge Urban History of Britain, 1: 600–1540, ed. D. Palliser (Cambridge, 2000), pp. 505–37.

- D. Woodward, ‘Wage rates and living standards in pre-industrial England’, Past & Present, xci (1981), 28–46, at p. 39.

- S. Broadberry, B. M. S. Campbell and B. van Leeuwen, ‘When did Britain industrialise? The sectoral distribution of the labour force and labour productivity in Britain, 1381–1851’, Explorations in Economic History, l (2013), 16–27, esp. p. 23. These figures may well be conservative as the paper assumes that women’s participation in the workforce was constant at 30%, whereas this chapter, and other work on servanthood and late marriage, indicates increased participation. For 1522 the only available database for rural England in 1522 was Rutland, a county where industrialization is likely to have been below average.

- B. M. S. Campbell, ‘The land’, in A Social History of England, 1200–1500, ed. R. Horrox and M. Ormrod (Cambridge, 2006), p. 221.

- Cheaper cloths used cheaper raw materials so labour was a higher percentage of production cost: wool alone accounting for 33–40% of cost.

- J. Patten, ‘Village and town: an occupational study’, Agricultural History Review, xx (1972), 1–16, at p. 13.

- Hatcher, ‘Unreal wages’.

- C. Dyer, ‘A small landowner in the fifteenth century’, Midland History, xiii (1972), 1–14; C. Dyer, ‘A Suffolk farmer in the fifteenth century’, Agricultural History Review, lv (2007), 1–22. The Warwickshire farmer, John Brome, operated a quarry and tile-works to supplement income from cattle rearing, while Robert Parman’s wife Joan managed an alehouse.

- J. Oldland, ‘The wealth of the trades in early-Tudor London’, London Journal, xxxi (2006), 127–56; J. Oldland, ‘The expansion of London’s overseas trade from 1475 to 1520’, in The Medieval Merchant: Proceedings of the 2012 Harlaxton Symposium, ed. C. M. Barron and A. F. Sutton(Donington, 2014), pp. 55–92. Wool income remained remarkably constant during the 15th century but declined in the 16th.

- All these counties were centres of woollen manufacture except Norfolk which dominated the market for worsteds.

- Broadberry and others, British Economic Growth, Appendix, pp. 80–2.

- Broadberry and others, British Economic Growth, Appendix, p. 106.

- Oldland, ‘Wool and cloth production’, p. 29.

- Broadberry and others, ‘British economic growth’, App. Figure A6.1 (B), from national income database.

- Broadberry and others, British Economic Growth, p. 204..

Chapter 12 (229-252) from Medieval Merchants and Money: Essays in Honour of James L. Bolton, edited by Martin Allen and Matthew Davies (Institute of Historical Research, School of Advanced Study, University of London, 06.30.2016), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons