Despite their common interests, relations between the foreigners and the Chinese community grew more tense during the early 19th century.

By Dr. Peter C. Perdue

Professor of History

Yale University

Despite their common interests, relations between the foreigners and the Chinese community grew more tense during the early 19th century. The increasing amount of trade and larger number of ships inevitably brought more conflict. The imperial court’s growing concern about the illegal opium trade led to more restrictions and anti-foreign attitudes, while the victories of the British in the Napoleonic wars bred more self-confidence and contempt for China’s resistance to opening additional ports to trade.

The “Terranova incident” of 1821 illustrated how the close and tense relationship between ships’ crews and sampan vendors could seriously endanger the entire China trade. Francis Terranova, an illiterate Italian seaman on the American ship Emily, was accused by the Chinese of killing a Chinese boat-woman with whom he had been bargaining. (Terranova allegedly threw an olive jar that hit her in the head, causing her to drown.) When the captain of the Emily refused to turn Terranova over for punishment, the Chinese suspended trade and arrested the hong merchant Eshing, who was not only responsible for the behavior of the foreigners but also owed large sums of money to the Americans. Confronted with this dilemma, and possibly to prevent the Chinese from inspecting the hold for smuggled opium, the Americans surrendered Terranova to the Chinese, who executed him by strangulation a few days later, notwithstanding assurances to the contrary. The incident shocked the foreign community, who regarded the trial as a mockery of justice. The British criticized the Americans for being too compliant toward the Chinese authorities:

As for the Americans who have thus barbarously abandoned a man serving under their flag to the sanguinary laws of this empire without an endeavour to obtain common justice for him, their conduct deserves to be held in eternal execration by every moral, honorable and feeling mind.

(Hosea Ballou Morse, Chronicles, volume 4, p. 26)

In Chinese eyes, honor and morality clearly resided on their side rather than that of the drug-dealing foreigners. The steady rise of illegal opium trade hardened the Chinese mood toward foreigners, who in turn resented their dependency on the Chinese who provisioned them and the officials who ruled them. When the British tried to bring a number of women into the factories in 1830, challenging official regulations, the women were quickly expelled. These tensions came to a head in the late 1830s, when the Canton system of Chinese control over the foreigners essentially entered its death throes, triggered in large part by the toxic mainstay of the Western export trade: opium. Nothing was the same thereafter—including even the spatial connections between the foreign factories and local Chinese community.

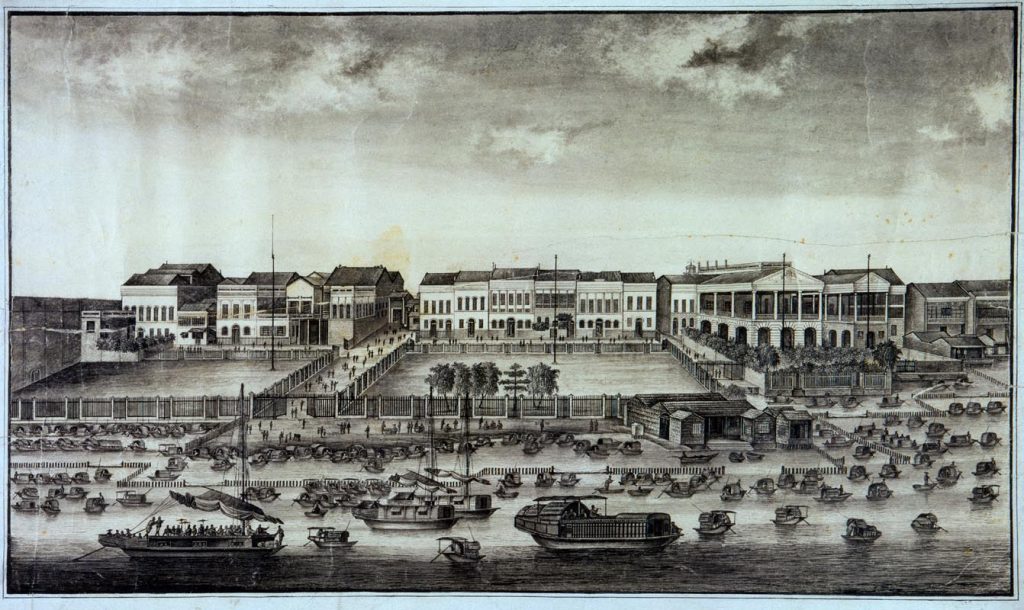

There is also the setting of Canton itself in the 1830s and ’40s, a hotbed of cultural and commercial competition in the period of the Opium Wars. Bounded to the south by the Pearl River and cut off from the general population by the city’s sizable and well-guarded walls, the claustrophobic foreign factory sector of Canton, adjacent to the old walled city was small enough to be measured in footsteps by its pent-up foreign occupants: 270 paces from one end to the other along the riverfront and a mere 50 from the shore to the shops and factories, or hongs, as they were called. On this strip of land, all of the trade between China and the West was carried.

out.(Stephen Rachman, Memento Morbi: Lam Qua’s Paintings, Peter Parker’s Patients)

Confronted by both the expiration of the East India Company’s monopoly in 1834 and a steady surge in opium smuggling by private traders, in 1838 and 1839 Chinese authorities attempted to crack down on the illegal drug trade by executing several Chinese opium dealers in the large open space between the factories and the Pearl River known as Respondentia Square—an unfenced area that functioned much like traditional Chinese open-air markets as a gathering place for vendors, entertainers, beggars, thieves, and occasional rowdy gangs. Several English sailors who were present tried to prevent the executions in 1839, but they came under attack by Chinese crowds and retreated to the factories for safety. The crowds drove out the local police and attacked the factories with stones and battering rams. Just as they broke into the English factory, Chinese troops arrived to disperse them.

Full-scale war erupted between China and Britain in 1839, after the Chinese attempted to cut off exports of tea, which Chinese authorities believed to be essential to the British economy. This, they hoped, would pressure England into suppressing opium smuggling. When the British responded instead by insisting on their right to trade freely in the illegal drug, the Chinese mobilized troops and ships to blockade the factories. The Chinese lost the Opium War when British ships bombarded Chinese forts and forced their way into Canton. The treaties that ended the war compelled the Chinese to allow free trade in opium as well as other goods, with a low fixed tariff.

During these years of conflict, while the warships fought at sea the merchants defended themselves by fencing in Respondentia Walk. After the Opium War, further riots led to the destruction of three factories. In response foreign merchants built the American Garden, a large space surrounded by a high fence designed to keep out the Chinese and provide recreation for Americans and Europeans within.

As the fences rose up, curious Chinese often pressed against them to watch the Westerners promenading in their cage. In a riot in 1846, the crowd chased an English merchant from Old China Street into a factory nearby, whereupon a detachment of armed foreigners marched out to break up the crowd, wounding and capturing several of them. After this riot, the foreigners obtained permission to block up the notorious Hog Lane, source of fires and troublemakers, and expand the American Garden. In 1847 an Anglican Church was built in front of the new factories, dominating most panoramic renderings and replacing the pagodas and mountains of earlier times.

Tension & Isolation in “The Square”

The increasingly isolated factories remained peaceful and undisturbed for a decade, but in 1856 another fire destroyed them completely, just as the Chinese and foreigners began mobilizing for a second Opium War. After their loss in this war, China had to open more treaty ports and allow foreigners access to the interior, but the foreign enclave in Canton still attracted a majority of the foreign traders. The entire trade area first moved to temporary quarters on Honam Island across the Pearl River, and then to a manmade island further up the river named Shamian. Shamian Island was entirely cut off from the local population, accessible only over two guarded bridges.

By the late 1850s the trading scene at and around Canton was flourishing as actively as ever. The great city maintained its dominant position for a long time, but competition from the newly opened treaty ports, especially Hong Kong and Shanghai, reduced its relative importance. Export paintings declined in popularity as photography arrived, and foreigners gained access to the interior. Images of China focused more widely on the entire empire, not just the limited foreign sector. Westerners now saw much more of China, but with a less intensive gaze, and religious and historical monuments replaced ships and traders as the primary subject of interest.

Bibliography

Brook, Timothy and Wakabayashi, Bob Tadashi, editors. Opium Regimes: China, Britain, and Japan, 1839–1952 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000).

Chaitkin, Anton. Treason in America: From Aaron Burr to Averell Harriman (New York: New Benjamin Franklin House, 1985).

Cheng, Christina Miu Bing. Macau: A Cultural Janus (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1999).

Cheong, W. E. The Hong Merchants of Canton: Chinese Merchants in Sino-Western Trade p. 71 (Routledge, 1997).

The China Trade and Its Influences, exhibition catalog (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1941).

The China Trade: Romance and Reality (De Cordova and Dana Museum and Park), an exhibition organized in collaboration with the Museum of the American China Trade, Milton, Mass., June 22 to Sept. 16, 1979 (Lincoln: De Cordova Museum, 1979).

Chu, Cindy Yik-yi, ed. Foreign communities in Hong Kong, 1840s–1950s, (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005).

Crossman, Carl L. The Decorative Arts of the China Trade: Paintings, Furnishings, and Exotic Curiosities (Woodbridge, Suffolk: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1991).

Dyce, Charles M. Personal Reminiscences of Thirty Years’ Residence in the Model Settlement Shanghai, 1870-1900 (Chapman & Hall, ltd., 1906)

Fay, Peter Ward. The Opium War, 1840–1842: Barbarians in the Celestial Empire in the Early Part of the Nineteenth Century and the War by Which They Forced Her Gates Ajar (New York: Norton, 1976).

Forbes, Robert Bennet. Personal Reminiscences, pp. 346-347 (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1882).

Frayler, John. Retired on the Fourth of Julyhttp://www.nps.gov/sama/historyculture/upload/Vol4No6WilliamStory.pdf

Grant, Frederic D. Jr. Hong Merchant Litigation in the American Courtshttp://www.grantboston.com/Articles/HMLitigation.pdf

Greenberg, Michael. British Trade and the Opening of China 1800-1842, p. 66

(Cam U Press Archive).

Gunn, Geoffrey C. Encountering Macau: a Portugese city-state on the periphery of China, 1557–1999 (Boulder: Westview Press, 1996).

Haddad, John Rogers. The Romance of China: Excursions to China in U. S. Culture, 1778-1876 (Columbia University Press, 2008).

History of the China Tradehttp://www.bl.uk/reshelp/findhelpregion/asia/china/guidesources/chinatrade/

Hudson, Geoffrey Francis. Europe & China; a Survey of Their Relations from the Earliest Times to 1800 (London, 1931: reprint Boston: Beacon Press, 1961).

Jourdain, Margaret and R. Soame Jenyns. Chinese Export Art in the 18th Century (London: Spring Books, 1967).

Kerr, Phyllis Forbes, editor. Letters from China: the Canton-Boston Correspondence of Robert Bennet Forbes, 1838-1840, (Mystic, Connecticut: Mystic Seaport Museum, 1996)

Lamas, Rosemarie Wank-Nolasco. Everything in Style: Harriett Low’s Macau (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press).

Loines, Elma. The China Trade Post-Bag of the Seth Low Family of Salem and New York, 1829–1873 (Manchester: Falmouth Pub. House, 1953).

Magazine Antiques, 1998, (Brant Publications, Inc. 1998)

Malcolm, Howard. Travels in South-Eastern Asia (Boston: Gould, Kendall, and Lincoln, 1839).

Map of the Eurasian Trade Routes in the 13th Century,http://www.drben.net/ChinaReport/Sources/China_Maps/China_Empire_History/Map-EurAsian_Trade_Routes-1200-1300AD-1A.html

Morse, Hosea Ballou. The Chronicles of the East India Company, Trading to China 1635–1834, volumes 1–5 (Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1926–29).

Munn, Christopher. Anglo-China: Chinese People and British Rule in Hong Kong, 1841–1880 (Richmond, Surrey: Curzon, 2001).

Paine, Ralph Delahaye. The Old Merchant Marine: a Chronicle of American Ships and Sailors (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1919; Toronto, Glasgow, Brook, & co., London, Humphrey Milford, Oxford University Press, 1921).

Smith, Philip Chadwick Foster. The Empress of China (Univ of Pennsylvania Press, 1984).

Sullivan, Michael. The Meeting of Eastern and Western Art (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997).

Tsang, Steve Yui-Sang. A Modern History of Hong Kong (London, New York: I.B. Tauris, 2007).

Turner, J.A. Kwang Tung or Five Years in South China, With an Introduction by H.J. Lethbridge (Hong Kong, Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 1894).

Views of the Pearl River Delta: Macau, Canton and Hong Kong, Exhibition Catalog (Hong Kong & Salem, Massachusetts: Hong Kong Museum of Art & Peabody Essex Museum, 1997).

Waley, Arthur. The Opium War Through Chinese Eyes (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1958).

Warner, John. Hong Kong Illustrated: Views and News, 1840–1890 (J. Warner, 1981).

Wei, Betty Peh-T’i. Ruan Yuan, 1764–1849: the Life and Work of a Major Scholar-Official in Nineteenth-Century China Before the Opium War (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2006).

White, Barbara-Sue, ed. Hong Kong: Somewhere Between Heaven and Earth (Oxford University Press, USA, 2006).

Wood, Frances. No Dogs and Not Many Chinese: Treaty-Port Life in China 1843–1943 (London: John Murray, 1998).

Zheng, Yangwen. The Social Life of Opium in China (Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

Originally published by Visualizing Cultures, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 United States license.