Conditions over vast expanses still demanded from would-be passengers solid motivations that can essentially come down to two sets of objectives.

By Dr. Damien Coulon

Professor of History

University of Strasbourg

Embarking on a journey to the Levant1 from the West, in the Middle Ages, was a risky venture that would require a good measure of audacity considering the perils that might lie in wait for the travellers, and the length of the route. Despite a context of progressive assertiveness of Christian Europe, in particular from the 11th century onwards, navigational conditions over vast expanses still demanded from would-be passengers solid motivations that can essentially come down to two sets of objectives. The first are religious in nature and refer us, on the one hand, to pilgrimages, which can be defined primarily as an individual quest. Indeed, even if Jerusalem was located several thousand miles away from the Christian West, the places where Christ had lived and undergone martyrdom began to attract pilgrims as early as Late Antiquity, and this activity increased during the Middle Ages as a whole despite the crusades against the Muslims, who had been living in that area since the great conquests of the 7th century. To the medieval mindset, these conflicts which aimed at establishing a Christian control over these supposedly sacred places were actually seen as “armed pilgrimages”. This phrase, which may sound quite contradictory today but was meaningful then, appeared in a context marked by the Church’s assertiveness.2 The armed character of these distant travels reflected very well the essential importance Christian Westerners attached to Jerusalem and the Holy Land in what was their medieval hierarchy of values. As they took the Cross, not only were they convinced that they were going on the most prestigious of pilgrimages but also that they were taking part in the “deliverance” of the tomb of Christ from the “infidels”.

The Levant also attracted other Western Christians, though this was for radically different reasons. Traders, in particular, would go to the Cairo or Damascus markets to purchase precious spices which very often came from more remote parts of the East. They also went to the quays of Acre, Beirut, and, most of all, to those of Alexandria. A little farther North, several branches of the Silk Road ended up on the shores of the Black Sea and in northern Syria. The Silk Road channelled across the heart of the Asian continent large quantities of very often high-priced textile products which would also interest Western traders.

As can be seen, few or no elements at all apparently predisposed the English to play a specific role in the Levant, mainly because of their geographic remoteness. Taking into account the maritime transportation then extant, journeys took longer than in our own time,3 circumstances of which would also make it more difficult to achieve a clear perception of the routes to follow. As early as in the mid-twelfth century, the famous chronicler Geoffrey of Monmouth involuntarily bore witness to this by recounting the unusual—to say the least—and, of course, partly symbolic, route followed by the legendary Brutus and his crew; indeed, hailing from Troy, they had reached Africa’s shores, then the Pillars of Hercules, but, according to this author, they then had to cross the Tyrrhenian (sic) Sea in order to reach Aquitaine, then the Loire river estuary and, eventually, England.4

Nevertheless, this very particular context, which focused the attention of European traders and pilgrims on the Near East, led English people to spend time regularly in this region, at least in the 12th and 13th centuries. But in so doing, some of them were also brought to deeply renew, in a pioneering and original way in the Western world, their perception and representation of the Mediterranean and Middle Eastern space.

Details about the crusades the English took part in during those two centuries are now well known and will not be developed here. Besides, they have already been engagingly introduced in high-standard essays which the interested reader may profitably refer to.5 However, I think three important remarks should be made within the framework of this paper.

First of all, despite the distance which stood between them and the Holy Land, the English took part in the expeditions to that region on a regular basis, especially from the 1147 second crusade onwards,6 until what historians have regarded as the eighth and ultimate one, which was led by Louis IX, i.e. Saint Louis, in 1270, and which Edward Longshanks—the future Edward I of England—joined. Unlike the French sovereign, who died at Tunis, Prince Edward actually reached Palestine with his troops. Thus began a long-lasting English presence in the Mediterranean and Middle Eastern space.6

Secondly, from the third crusade onwards, in 1190-1192, Western troops—the Germanic contingents excepted—were primarily sent to the Holy Land following a sea route, unlike the first expeditions which were nearly always terrestrial. This mode of transport, which indeed made it possible to cover longer distances and save the troops’ energy prior to their deployment, facilitated the sending of northern Europe crusaders, particularly English ones, thanks to their own fleets.

Lastly, it is important to emphasize the fact that some English contingents were far from negligible; they were even the largest of the third crusade—in which Richard the Lionheart took part in 1191-1192, after Saladin’s recapture of Jerusalem—as well as of the 1227 expedition, led by the bishops of Winchester and Exeter, and that of 1240, led by Richard, 1st Earl of Cornwall.7

If these events and the role played by the English are well documented, on the other hand it seems to me that the attention of historians has less been drawn to a yet quite telling phenomenon, and that is the geographical and cartographic musings the successive expeditions aroused in England and which have recently brought about a significant historiographical renewal.

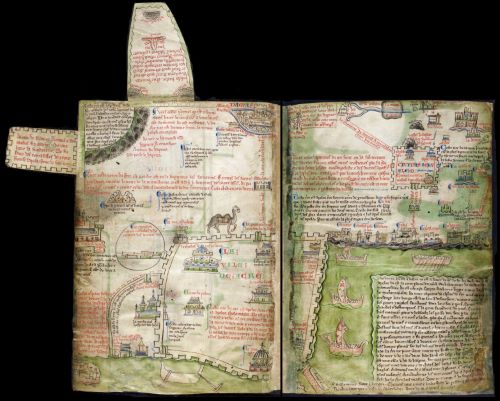

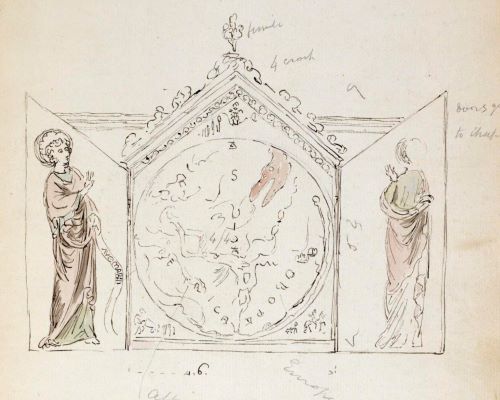

It is indeed known that the principal cartography established during the 12th and 13th centuries wore the shape of the famous maps representing the whole (so it was then thought) of the extant world, which they usually displayed in circular form comprising the Old World’s three landmasses—Asia, Europe and Africa—with their little realistic outlines. Sawley’s and Hereford’s famous world maps furnish good examples.8 Incidentally, this kind of representation has led us believe for a long time that the medieval imago mundi amounted to a flat disc floating on water. This idea still endures today to a large extent and conveys the notion of the Middle Ages as dark ages. But nothing could be further from the truth; well-read people of the Middle Ages knew for a fact that the Earth was a sphere, as was recounted by some travelers or storytellers such as John Mandeville, who clearly alluded to the Earth’s circularity in his astonishing narrative,9 as well as by some theologians, in particular Hugh of Saint Victor, Robert Grosseteste, and, of course, geographers like Gautier de Metz, as the latter’s illustrations unequivocally show.10 As a matter of fact, this way of representing the three landmasses on the maps simply was consistent with a bidimensional graphic convention then in use in the Western world.

Recent historiography has shown that these mappae mundi originated with one unique type of representation, though they could be adapted to quite different formats, for example small ones in books or large ones for maps exhibited in churches such as those at Hereford and Ebstorf. Above all, this kind of representation actually seems to have proceeded from a common geographical birthplace, since it has now been firmly established that it “was favoured in northern European countries, in particular England” in the 12th and 13th centuries.11 The well-known maps called the Psalter World Map and the Sawley Map, dating back to the 12th century, and the 13th century Hereford Mappa Mundi clearly establish the fact.

Besides, it is a commonplace—albeit an important one—to recall that these maps, being above all the product of a symbolic approach and emphasizing the importance of biblical traditions, also favour the Holy Land and Jerusalem area, generally located at their centre, though this is not systematic, since for example the Sawley Map is centred on the island of Delos, thus respecting an antique Greek heritage.12 Obviously, these rules of representation did not integrate the concrete observations sometimes directly reported by crusaders or pilgrims, but they did tally with their project and objective by highlighting the Holy Land, which was positioned “in the middle of the oecumene, at the intersection of the three parts of the world”.13

However, a better documented case shows that a more obvious link can be established between an actual participation in the crusade and an in-depth cartogeographic work. This is what historian P. Gautier-Dalché has endeavoured to show in his essay Du Yorkshire à l’Inde. Une « géographie » urbaine et maritime de la fin du xiie siècle (Roger de Howden ?), published in 2005, and which focuses on the figure of an English chronicler, Roger of Hoveden, who took part in the third crusade.14

In his book, P. Gautier-Dalché has highlighted the existence of three texts preserved in two manuscripts that aimed at spreading the same geographical knowledge, though with quite distinct approaches, in the first place a cartographic one in a work entitled Expositio mappe mundi, which is a thirty-page long description of an un-reproduced world map, in the second place a nautical one in an eight-page booklet entitled Liber nautarum, and, finally, a geographical perspective in the sixty-page De Viis Maris text.

One of the main difficulties about their analysis comes from the fact that these texts have remained anonymous. However, a set of convincing arguments leads us to believe that they did have one single author, in particular their common geographical origin, which can be deduced from their contents—Yorkshire.15 Though he cannot prove it indisputably, P. Gautier-Dalché believes that this author probably was a chronicler at the courts of Henry II of England then Richard the Lionheart. His name was Roger of Hoveden, and several historians suppose that he moreover left behind him two historiographical narratives entitled Gesta and Chronica. Now, these obviously indicate an empirical knowledge of the Holy Land, where Roger probably stayed between the spring of 1190 and the summer of 1191, if we take into account the details he gave in relation to the third crusade. These observations eventually make it possible for historians to deduce that he actually accompanied Richard I on his outward journey to the Levant, then Philip II of France, on his return.16

The content of these three texts is relevant to our subject; in the first place, the Expositio mappe mundi describes in minute detail a world map strangely similar to the Hereford Mappa Mundi though it is, as seen before, one century older, thus adding an English copy—or at least a copy resorted to in England—to those we are already familiar with. Significantly, P. Gautier-Dalché notes that the Hereford Mappa Mundi seems to differ from the one used by the author of the Expositio mappe mundi only in some secondary aspects, one of which being a highlighting of the Holy Land in its centre,17 as we have seen. Besides, the precisely described route in the De Viis Maris does link England to the Levant while extending it as far as India.18

A final point deserves consideration, that of the author’s intellectual biography and the source material he used. If it was indeed Roger of Hoveden, we also know that he enjoyed the patronage of the Bishop of Durham, Hugh de Puiset19 (1153-1195), who obviously influenced Roger’s historical works in a decisive way. Now, as P. Gautier-Dalché has shown once again, this intellectual took part in “diverse undertakings of a geographical and cartographical nature” from which Roger was able to access a large amount of information.20

It results from the study of these elements that an English protagonist wished to emphasize, in an original and varied written form, his geographical and nautical knowledge as well as his experience of a journey to the Holy Land. This activity, though not an isolated case in Europe, still was original for a late twelfth-century Englishman.

As it happens, a distinct and better known example of an even more original route, written by another Englishman a little time after Roger of Hoveden, ought in my view to be mentioned here as well though its author, Matthew Paris, never went to the Levant. This Benedictine monk, who lived at St Albans Abbey and died in 1259, is indeed famous for having left several written accounts “richly illuminated and also illustrated with maps that show evidence of their author’s interest in various ways of representing space”.21 As E. Vagnon notices, “M. Paris’s representation of the Near East particularly took on two very distinct aspects which appeared to complement each other”.22 The first map, quite sober in its design, was actually integrated into the final pages of a Bible. He drew it himself around the middle of the 13th century, perhaps as early as 1235;23 facing north, the map positions the Holy Land between Antioch (Antakya) and Alexandria, and from the Jordan River24 to the Mediterranean Sea, all of it within a rectangular frame. Realistically, Jerusalem is not located at its centre but is highlighted by a somewhat larger vignette.

However, the second map turns out to be quite different and is integrated into a very original kind of document, the famous itinerary from London to Apulia, southern Italy, designed for pilgrims by Matthew Paris in the form of a series of more or less developed urban vignettes, depending on the size of the towns that marked out the itinerary. As it happens, the last of these maps focuses on the Holy Land as if, from southern Italy, Matthew Paris had invited his page-turning readers to symbolically cross the eastern Mediterranean Sea and reach Palestine, as has been stressed by some authors.25 But this new map is more elaborated and contains written notes that are much more developed than those found in the first one.

However, in both cases the representation of Palestine is based on a new and more realistic approach which emphasizes the land’s actual topography, notably by lending St. John d’Acre’s vast harbour a particular importance, so much so that, on both maps, it even pushes into the background the city of Jerusalem.26 Lastly, one of the elements that deserves emphasis is the particularly original character of Matthew Paris’Itinerary, the progress of which thus led one to the map of the Holy Land; indeed, if numerous written accounts of the 12th and 13th centuries itineraries are at hand —the De viis maris is of course a good example—this way of mapping, halfway between text and illustration, was quite exceptional.27

It is well known that the late 13th century was marked successively by the failure of the last crusade, then by the definitive recapture of the Holy Land’s last Latin states by the Mamluks, in 1291.28 From then on, the English—as well as other peoples from the shores of the North Sea—no longer travelled there collectively. Nor did they sail across the Mediterranean Sea anymore. On an individual basis, some did perpetuate the tradition of the great pilgrimage in the 14th and 15th centuries, such as Margery Kempe, an exceptional example of a pilgrim woman who not only wrote a narrative of her pilgrimage to the Holy Land circa 1415, but also narratives of her extensive travels.29 Later on, pilgrim William Wey did add a map to the narrative of his 1458 and 1462 pilgrimages,30 but it was actually inspired by an ancient model, tested out by Venetian geographer Marino Sanuto of Torcello (1270-1343) in relation to his aim at reviving the crusades in the early 14th century—a project which never saw the light of day.31 It seems therefore that cartographic production and original geographical reflection pertaining to the Levantine Sea are no longer to be found in England from the late 13th century onwards.

John Mandeville is nevertheless quite a particular exception. It is known that despite the fact that he claimed, in the travel memoir he wrote in 1355-1356, to be an English knight from St Albans, his identity actually remains something of a mystery, and it is now established that the first version of his work was not written in English but in French.32 Even so, it seems significant to me to bring together several essential points; to begin with, the author’s so-called English birth plus the fact that his work was a complete success in England, in the French language, then in English.33 Secondly, Mandeville’s Book is an early and original development of a geographical approach specialists have never failed to point out,34 and in which the Holy Land and the Levantine Sea are extensively dealt with. More precisely, eleven chapters35 are devoted to this area, out of a total of thirty-four covering the then three known continents. Of course, the itineraries to Jerusalem, in this original geography, constitute particularly highlighted roadways.36 In other words, a wide English readership became closely interested in his narrative, and consequently in his geographical approach. Mandeville was possibly better prepared than others, not only because he claimed to be an Englishman, which actually was not questioned in the Middle Ages.

To conclude, I think it is important to stress the fact that the Middle East, a faraway clime, albeit one frequented by the English, especially in the 12th and 13th centuries, was tied to significant plans and pursuits that compelled them, for the first time in their history, to project themselves into a distant elsewhere, well before the initial colonial conquests. This initiative was actually the cause and the consequence of travels to the Levant. The point for some English intellectuals, whether they went there or not, was to achieve a synthesis of the acquired knowledge pertaining to this region of the world but also to describe in a more and more practical and realistic way the itineraries that led there. These attempts at a geographical awareness in particular seem to proceed from episcopal sees, especially those at Durham, Hereford and York, while the bishops of Winchester and Exeter, as has been seen, set up and led in person the expeditions to the Holy Land. These scholarly initiatives which greatly value cartography and geography—more specifically that of the Holy Land and the routes leading there with England as a starting point—are based on the actually original setting up of maritime expeditions directly captained by Englishmen even if, once in the Mediterranean Sea, they may have mingled with other fleets. Indeed, among the foremost nations encountered in the region, the continental Germans would logically use a more direct land route, while the French would often resort to Italian, Venetian and Genoese ships as troop transports, at least until the mid-thirteenth century.37

Besides, this new geographical approach resting to a large extent on concrete data—probably brought back by crusaders—is however no substitute for the tradition of ecumenical world maps, as the late—c. 1300—Hereford Mappa Mundi, again, noteworthily exemplifies. Thus, two different forms of cartographic and geographical approach gradually became entangled; on the one hand, a traditional vision relying to a large extent on a symbolic logic. On the other hand, an early combination of new and varied descriptions which, because of their more and more realistic and concrete substance, would be used as reference works by new travellers.38 These two concomitant perspectives are not specific to England. They show that at a time when new travellers tried to bring up to date their knowledge of the far-away Levant, many scholars went on displaying, on maps or in books, principles and myths reported by ancient writers, in particular Pliny the Elder, Gaius Julius Solinus and Isidore of Seville, and even present in biblical narratives, which were still authoritative by the late Middle Ages. Only our modern mind will find the interference between these two approaches puzzling.

The new attempts at map projection made in England thus were original in two ways. Firstly, they were distinct from those actually produced later, from the early 14th century onwards, by Mediterranean cartographers. As we know, the famous nautical, or portolan, charts originated with Italians—especially Venetians and Genoese—and Majorcans. They had nothing in common with the English experiences described here and were characterized, among other things, by the remarkable quality of the layout of the Mediterranean coastline. From these essential differences, distinct representations and projections of space seem to emerge, and even, through them, different identities.39

Secondly, another original specificity of this first experience of English people journeying to the Levant deserves mention—their non-commercial character. We nevertheless know that the Mediterranean Sea was crossed by more and more Western traders, from the 10th-11th centuries onwards. By the late Middle Ages, these were primarily Italians, Catalans, Majorcans and secondarily French, Castilians, Portuguese and Basques. From a time-spanning perspective, and considering in particular the conquests and the later exploitation colonialism, these first English expeditions to the Levant which occurred in the 12th and 13th centuries should also be perceived as quite original events rich in remarkable potentialities waiting to unfold.

See endnotes and bibliography at source.

Section II, Pages 59-69, from Geographies of Contact: Britain, the Middle East and the Circulation of Knowledge, edited by Caroline Lehni, Fanny Moghaddassi, Hélène Ibata and Nader Nasiri-Moghaddam (Presses universitaires de Strasbourg, 10.14.2019), published by OpenEdition Books under an Open Access license.