When dreams of democracy contended with the realities of empire and oil.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The history of Iran between the late 18th century and the mid-20th century is a turbulent saga of dynastic decline, imperial entanglement, nationalist awakening, and political rupture. The period from the founding of the Qajar dynasty in 1796 to the Anglo-American coup of 1953 encapsulates Iran’s struggle to maintain sovereignty amid the crosscurrents of internal weakness and foreign domination. The Qajar monarchs, the constitutional revolutionaries, the Pahlavi autocrats, and the democratic aspirations of figures like Mohammad Mossadegh all left indelible marks on the formation of modern Iranian identity and statehood.

The Rise and Rule of the Qajar Dynasty (1796–1925)

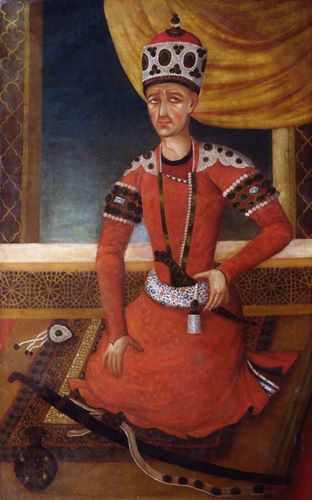

The Qajar dynasty emerged at a time when Iran was reeling from the disintegration of centralized Safavid rule and the chaos of successive tribal wars. Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar, the dynasty’s founder, was a eunuch from the Qajar tribe who had served in various royal courts before asserting his own claim to leadership. After subduing rival factions and defeating the remnants of the Zand dynasty, he declared himself Shah in 1796 and established his capital in Tehran—a city he chose for its strategic centrality rather than historical prestige.1 His reign was marked by brutal campaigns to consolidate authority, most infamously the massacre of the population of Kerman, but he succeeded in reuniting Iran as a cohesive if fragile political entity. His assassination in 1797 ushered in the reign of Fath-Ali Shah, under whom Iran would suffer the first of many humiliations at the hands of imperial powers.

The 19th century for the Qajar dynasty was characterized by military weakness and diplomatic failure, particularly in their dealings with Russia. The Russo-Persian Wars (1804–1813 and 1826–1828) resulted in devastating territorial losses through the Treaties of Gulistan and Turkmenchay, in which Iran ceded large parts of the Caucasus, including modern-day Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan.2 These defeats exposed the antiquated nature of Iran’s military and administrative systems and revealed the Qajar state’s vulnerability to imperial aggression. Attempts at military modernization by figures such as Abbas Mirza, Fath-Ali Shah’s son, introduced Western-style training and equipment but were undercut by financial instability and factionalism at court.3 The treaties also opened Iran to a flood of diplomatic and commercial interference, particularly by the British and Russians, who would play increasingly manipulative roles in Iranian internal affairs.

One of the defining features of Qajar rule was the selling of economic concessions to foreign powers, often in exchange for bribes or loans that sustained the extravagant lifestyles of the royal court. The most notorious example of this was the 1890 tobacco concession granted by Nasir al-Din Shah to a British company, giving it exclusive rights over the production, sale, and export of tobacco. This concession triggered a nationwide protest movement—the Tobacco Revolt—led by a unique coalition of merchants, clerics, and common citizens, marking an early manifestation of mass political mobilization in modern Iran.4 The boycott, which forced the Shah to cancel the concession, revealed the deep-rooted resentment against foreign control and planted seeds of constitutionalism by demonstrating the power of collective action and clerical legitimacy in political resistance. The revolt also marked the beginning of the political awakening of the Iranian middle class and merchant elite.

The culmination of widespread dissatisfaction with Qajar misrule came with the Constitutional Revolution of 1905–1911, during the reign of Mozaffar al-Din Shah. Triggered by economic hardship, administrative corruption, and resentment over foreign dominance, the revolution led to the establishment of a majles (parliament) and the drafting of Iran’s first constitution in 1906.5 Though the revolution aimed to transform Iran into a constitutional monarchy modeled on European systems, it faced fierce opposition from the monarchy, conservative clerics, and foreign powers—especially Russia, which intervened militarily to suppress the movement. The fragile constitutional order was repeatedly undermined by coups, factionalism, and foreign intervention, leaving Iran in a state of semi-chaos. While the revolution was ultimately stifled, it established a precedent for legal reform, representative government, and public discourse on the limits of royal power.

The final decades of Qajar rule were defined by further national decline, as World War I turned Iran into a battleground for competing foreign armies despite its declared neutrality. Widespread famine, economic collapse, and the collapse of central authority paved the way for military figures to fill the power vacuum. Chief among them was Reza Khan, a military officer who staged a coup in 1921 and gradually consolidated control. With support from Britain and a growing nationalist movement disillusioned with dynastic incompetence, Reza Khan forced the abdication of Ahmad Shah Qajar—the last Qajar monarch—in 1925 and established the Pahlavi dynasty.6 Thus, the Qajar era ended as it began: with the concentration of power in a single strongman seeking to restore order to a fractured land. Yet the legacy of the Qajars, especially in the form of constitutional aspirations and the politicization of the clerical and merchant classes, would endure and reemerge throughout Iran’s subsequent modern history.

The Constitutional Revolution (1905–1911)

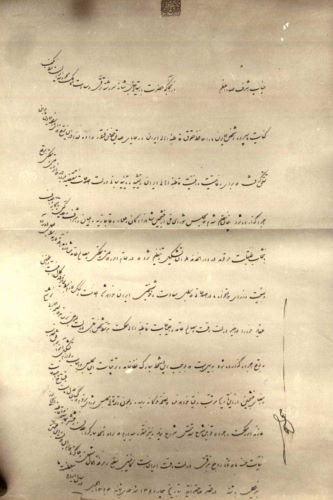

The Iranian Constitutional Revolution of 1905–1911 represented the first significant mass movement in the modern Middle East to demand constitutional governance and the rule of law. Rooted in growing discontent with the autocracy of the Qajar dynasty, the revolution was sparked by a convergence of economic hardship, political repression, and resentment toward foreign interference—particularly by Britain and Russia. The immediate catalyst came in 1905 when a group of Tehran bazaaris (market merchants) were publicly flogged for price gouging. This humiliation inflamed broader frustrations with state corruption, inflation, and arbitrary governance, leading to widespread demonstrations by merchants, clerics, and intellectuals demanding reform.7 The protests escalated into a national movement, culminating in the 1906 concession by Mozaffar al-Din Shah to establish a national parliament, or Majles, and a written constitution. This was a monumental departure from centuries of patrimonial monarchy and signaled a profound political awakening among Iran’s emerging civil society.

The 1906 constitution was a hybrid document blending Islamic concepts of justice with European liberalism, influenced by Belgian and French constitutional models. It declared the equality of all Iranians before the law, protected property rights, and established a representative legislature with the authority to approve budgets and review laws.8 Importantly, it also created a balance—albeit fragile—between the monarchy and elected representatives. However, tensions emerged almost immediately between competing visions of Iran’s future. Clerics like Sheikh Fazlollah Nouri supported the constitution only insofar as it upheld Islamic values, while secular intellectuals and modernist ulama pushed for a more progressive and nationalistic system. This ideological friction, combined with the monarchy’s reluctance to cede real power, laid the groundwork for future conflict. Nevertheless, the Majles became a vital symbol of national sovereignty and civic participation, despite its limited powers and uneven enforcement.

The brief democratic experiment was soon imperiled by reactionary backlash. In 1907, following the death of Mozaffar al-Din Shah, his son Mohammad Ali Shah ascended the throne with little regard for constitutionalism. With military and financial backing from Tsarist Russia, he launched a coup in 1908, bombarding the Majles building and arresting or executing leading constitutionalists.9 This act of aggression triggered a nationwide civil war between royalist forces and constitutionalist militias—most notably from Tabriz, Isfahan, and Gilan—who fought to restore the constitution. Among the key leaders of this resistance were figures like Sattar Khan and Baqer Khan, who organized popular defenses and reinvigorated the revolutionary cause. By July 1909, the constitutionalist forces had marched on Tehran and deposed Mohammad Ali Shah, reinstating the constitution and installing his young son, Ahmad Shah, as a nominal monarch under a regency.

Although the revolution was momentarily revived, it entered a second phase characterized by deep internal divisions, foreign occupation, and financial insolvency. The new Majles was burdened with the challenge of governing a fractured country, managing foreign debt, and confronting the entrenchment of foreign influence. Britain and Russia had, in the 1907 Anglo-Russian Convention, effectively divided Iran into zones of influence without Iranian consent, undermining the very sovereignty the constitutionalists had fought to achieve.10 Moreover, debates over the role of religion in the state, property rights, and land reform fractured the fragile coalition that had supported the revolution. Conservative clerics withdrew support, and tribal leaders reverted to traditional allegiances, while socialists, liberals, and nationalists clashed over the direction of reform. Despite these setbacks, the revolution created a new political vocabulary—centered on law, representation, and nationhood—that would persist throughout the 20th century.

The Constitutional Revolution ultimately failed to create a stable constitutional order, but its legacy was profound. It inaugurated Iran’s modern political consciousness, established the Majles as a central institution, and catalyzed debates over national identity, civil rights, and clerical authority that would echo in later upheavals, including the 1979 revolution. Though Iran fell back into autocracy during the reigns of Reza Shah and his son, the ideals of constitutionalism endured as a latent force in Iranian political culture. The revolution also helped usher in new social actors—urban middle classes, intelligentsia, and nationalist clerics—who would continue to challenge the status quo. While the constitutionalists failed to permanently constrain monarchical power, they succeeded in embedding a vision of accountable governance and national dignity that continued to inspire reformers and revolutionaries long after their apparent defeat.11

The Rise of Reza Shah and the End of the Qajars (1921–1925)

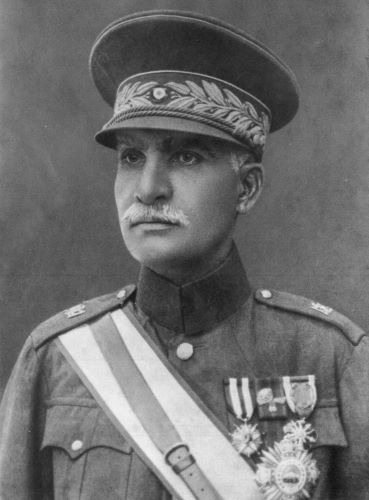

The final collapse of the Qajar dynasty and the rise of Reza Khan—later Reza Shah Pahlavi—must be understood within the broader context of national disintegration, foreign occupation, and revolutionary aftershocks in the early 20th century. In the aftermath of World War I, Iran lay in ruins. Though officially neutral, the country was occupied by British, Russian, and Ottoman forces. Widespread famine, economic devastation, and social fragmentation plagued the Qajar state, whose authority had already been eroded by decades of internal misrule and foreign intervention.12 The weak and ineffectual rule of Ahmad Shah Qajar, the last monarch of the dynasty, further undermined the throne’s legitimacy. With no standing army, depleted finances, and widespread provincial autonomy, the central government was largely a fiction by 1920. In this vacuum, new figures emerged, most notably Reza Khan, a military officer of humble origins who would soon become the architect of a new authoritarian order.

Reza Khan began his ascent in the Persian Cossack Brigade—a military force originally created and trained under Russian command. In February 1921, he staged a bloodless coup in Tehran in collaboration with Sayyed Zia al-Din Tabataba’i, a reform-minded journalist who briefly served as prime minister following the coup.13 Reza Khan became Minister of War and quickly began consolidating power. While Zia was dismissed after only three months, Reza remained, using his military command and nationalist rhetoric to project strength in a country desperate for order. Over the next few years, he embarked on a campaign to pacify the provinces, suppress tribal revolts, and reduce the influence of regional warlords and clerical authorities. His efforts to centralize the state through military force and administrative expansion won him the support of a broad cross-section of the elite—reformist intellectuals, merchants, and technocrats—who viewed him as a necessary bulwark against chaos.

Between 1921 and 1925, Reza Khan increasingly positioned himself as the only viable alternative to Qajar impotence. He first served as Minister of War, then as Prime Minister (from 1923), carefully cultivating a nationalist image while dismantling the old aristocratic order. His policies promoted a secular, modernist vision of Iran, with an emphasis on law and order, a standing army, and infrastructural development.14 Many constitutionalists—disillusioned by the failures of the 1906 revolution—supported his authoritarianism as a means of completing the national project they had begun. Meanwhile, foreign powers, especially Britain, viewed him as a useful ally who could stabilize Iran and protect British interests in the region. Though Reza publicly denounced foreign influence, he benefited from British logistical and political support, particularly in suppressing leftist uprisings and maintaining control over oil-rich regions in the south.

Ahmad Shah, increasingly absent from governance and often abroad in Europe, made little effort to resist Reza Khan’s gradual assumption of authority. In 1925, the Majles—under Reza’s growing influence—voted to depose the Qajar dynasty and abolish hereditary succession in favor of a new constitutional monarchy.15 Reza Khan was crowned Reza Shah Pahlavi on December 15, 1925, inaugurating the Pahlavi dynasty. The constitutional mechanisms used to transfer power gave a veneer of legality to what was, in essence, a military-backed seizure of the throne. Yet Reza Shah did not present himself as a usurper. Rather, he invoked the legacy of ancient Persian kingship—particularly that of Cyrus and Darius the Great—to frame his rule as a restoration of national greatness rather than a rupture with tradition. His reign would mark a new era of aggressive state-building, secular reform, and nationalist consolidation.

The fall of the Qajars marked the end of Iran’s long experiment with a decaying patrimonial monarchy that had proven incapable of adapting to modernity. While the constitutional revolution had introduced new institutions and ideas, it was Reza Shah who succeeded in institutionalizing state authority and imposing a modern bureaucratic order—albeit through autocratic means. His rise also signaled a shift in the locus of power from dynastic aristocracy to militarized bureaucracy, setting the stage for the centralized, state-led modernization programs of the 1930s. Although his methods were often coercive, Reza Shah’s ascent reflected the aspirations of many Iranians who yearned for stability, national dignity, and liberation from foreign domination.16 The transition from Qajar to Pahlavi rule thus encapsulated both the failure of constitutionalism and the triumph of authoritarian modernism in the first phase of Iran’s 20th-century transformation.

World War II and the Abdication of Reza Shah

Reza Shah’s aggressive campaign of centralization and modernization in the 1930s brought dramatic changes to Iranian society, but it also sowed the seeds of growing discontent both domestically and internationally. His emphasis on secularization, bureaucratic expansion, and compulsory state education aimed to create a strong, unified nation-state modeled on European prototypes. However, these reforms often alienated traditional power bases, including the clerical establishment, tribal leaders, and sections of the bazaar merchant class. Reza Shah’s repression of dissent, coupled with his rigid control over the press and public life, created a climate of authoritarian stagnation masked as progress.17 Yet it was not internal dissent, but rather global geopolitical conflict, that would bring his reign to an abrupt end. The outbreak of World War II placed Iran once again at the strategic crossroads of great power competition—this time between Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union, and the Western Allies.

Despite his professed neutrality, Reza Shah’s foreign policy during the late 1930s increasingly leaned toward Germany, which had become Iran’s largest trading partner by the outbreak of the war. Seeking to reduce British and Soviet influence, the Shah welcomed German engineers, technicians, and advisors—many of whom were suspected of espionage. Although Reza Shah hoped to preserve Iranian sovereignty through a policy of “neutral equidistance,” this posture was interpreted by Britain and the Soviet Union as a pro-Axis tilt.18 Iran’s geographic position and vital oil reserves rendered it indispensable to Allied strategic planning, particularly as a corridor for supplying the Soviet war effort through what became known as the “Persian Corridor.” Fearing sabotage and German penetration, the Allies issued several ultimatums demanding the expulsion of Axis nationals from Iran—demands which Reza Shah either ignored or only partially fulfilled.

In August 1941, after failed negotiations, British and Soviet forces launched a joint invasion of Iran under the pretext of securing supply lines and protecting the region from Axis influence. Operation Countenance was swift and largely unopposed, as Iranian forces were vastly outmatched and demoralized. Within days, the Allies had seized key cities including Tehran, and the Iranian army was effectively neutralized. Although Reza Shah attempted to negotiate, the Allies made it clear that his continued rule was unacceptable due to his perceived pro-German sympathies.19 On September 16, 1941, under intense pressure from the occupying powers, Reza Shah abdicated in favor of his son, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who was viewed as more pliable and amenable to Allied interests. The elder Shah was forced into exile, eventually settling in Johannesburg, South Africa, where he died in 1944.

The abdication of Reza Shah marked a critical turning point in Iranian political life. Though the monarchy remained intact under Mohammad Reza Shah, the occupation shattered the aura of invincibility that Reza Shah had cultivated during his two decades of rule. Allied control over Iran introduced a new period of political liberalization, as censorship was relaxed, political parties reemerged, and civil society experienced a renaissance. Groups ranging from liberal constitutionalists to Marxists and Islamists took advantage of this opening to reassert their place in public life.20 Yet the Allies also retained considerable influence over Iranian affairs, controlling transportation networks, managing economic policy, and even shaping the selection of government ministers. This dual reality—a young and insecure monarch reigning under foreign supervision amidst a politically awakened populace—set the stage for the turbulent decades to follow.

Despite the humiliation of invasion and occupation, the wartime years also fostered important structural transformations. The Allied presence accelerated industrial development, improved infrastructure, and established new educational institutions. However, these benefits were unevenly distributed, and wartime inflation, food shortages, and corruption eroded popular trust in the state. Moreover, the 1943 Tehran Conference, attended by Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin, reaffirmed Iran’s independence but did little to curtail foreign dominance in practice.21 The legacy of Reza Shah’s abdication was thus a paradox: his downfall enabled a partial democratic opening and new political energies, but also entrenched Iran’s role as a pawn in global geopolitics. For many Iranians, the war years would come to symbolize both the possibilities of national revival and the stark limits imposed by external interference—dynamics that would resurface again during the crisis of 1953.

Oil, Nationalism, and the Rise of Mohammad Mossadegh

The postwar years in Iran were marked by political pluralism, economic instability, and mounting nationalist sentiment, particularly around the issue of oil. Although Iran had regained nominal sovereignty following the withdrawal of Allied forces in 1946, its most valuable natural resource remained under foreign control. The Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC), majority-owned by the British government, reaped enormous profits from Iranian oil while paying the Iranian state only a fraction of the revenues.22 The inequities of this arrangement sparked outrage across the political spectrum. By the late 1940s, oil had become a symbol of broader foreign exploitation and national humiliation, crystallizing Iranian demands for true independence. It was in this atmosphere that Mohammad Mossadegh—an elder statesman known for his integrity, legal acumen, and unwavering nationalism—emerged as the central figure of a movement to reclaim Iran’s resources and redefine its political destiny.

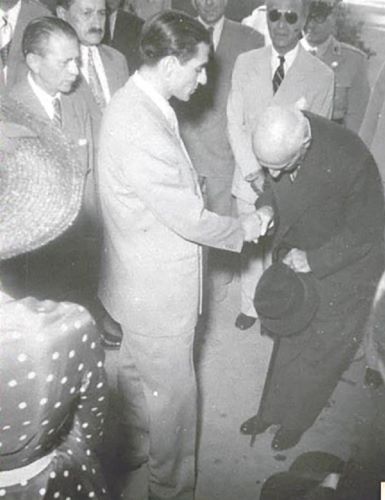

Mossadegh had long been involved in Iranian politics as a constitutionalist and critic of autocracy. A member of the National Front, a coalition of nationalists, liberals, and secular intellectuals, he advocated for parliamentary sovereignty, civil liberties, and the expulsion of foreign influence. His political career was defined by a consistent opposition to despotism, both foreign and domestic. In 1951, following a surge in public support and mounting frustration with British intransigence, Mossadegh led the Majles to pass legislation nationalizing the AIOC, thereby creating the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC).23 The move electrified the country and catapulted Mossadegh to the premiership. For many Iranians, he represented the long-deferred promise of the Constitutional Revolution—a leader committed to the rule of law, accountable government, and national dignity.

The nationalization triggered an immediate crisis. Britain responded with a global boycott of Iranian oil, legal challenges at the International Court of Justice, and covert efforts to destabilize Mossadegh’s government. The British blockade devastated Iran’s economy, causing inflation and revenue loss, but Mossadegh’s popularity soared due to his defiance. In 1952, he resigned temporarily when the Shah refused to grant him emergency powers, but massive street protests forced the monarch to reinstate him with expanded authority.24 Mossadegh used his enhanced powers to push for land reform, curb royal influence, and reduce the power of the military. However, his position became increasingly precarious. Economic hardship, political infighting, and opposition from conservative clerics and landowners eroded his support base. Simultaneously, British officials, having been expelled from Iran, turned to the United States to engineer Mossadegh’s removal, portraying him as a potential ally of communists amid the Cold War.

American attitudes toward Mossadegh were initially ambivalent. While some U.S. officials admired his democratic ideals, others feared the growing influence of the Tudeh Party, Iran’s communist organization, which had begun supporting his nationalist agenda. In the climate of Cold War paranoia, even the appearance of communist sympathy was sufficient to provoke alarm in Washington. By 1953, the CIA and MI6 jointly launched Operation Ajax, a covert operation to orchestrate a coup against Mossadegh.25 After an initial failure on August 15, loyalist forces regrouped, and on August 19, aided by military officers, paid mobs, and political agitators, the coup succeeded. Mossadegh was arrested, tried, and placed under house arrest for the rest of his life. The Shah returned to power with full support from the United States and Britain, ushering in a period of autocratic rule that would last until the Islamic Revolution of 1979.

The fall of Mossadegh marked a profound rupture in Iran’s modern political development. It extinguished the country’s most promising experiment in parliamentary democracy and entrenched a regime dependent on Western support and resistant to popular accountability. Though Mossadegh was vilified by his opponents as a demagogue and opportunist, he was revered by supporters as a martyr for national sovereignty and democratic values.26 The oil nationalization campaign inspired anticolonial movements around the world and reshaped the geopolitics of the Middle East. More enduringly, it seeded a deep and abiding distrust of foreign intervention among Iranians—particularly of British and American motives—that would reverberate for decades. Mossadegh’s legacy, though cut short, continued to loom large over Iran’s political consciousness, not as a failure, but as a foretaste of what an independent and democratic Iran might have become.

The 1953 Coup d’État

The coup d’état of August 1953 stands as one of the most consequential turning points in modern Iranian history and a watershed moment in U.S.–Middle East relations. Known internally as the 28 Mordad coup and externally as Operation Ajax, the event was a calculated, covert operation orchestrated by the United States’ Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in collaboration with the British Secret Intelligence Service (MI6). Its primary goal was the removal of Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh and the restoration of full monarchical power to Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi. The coup was fueled by a convergence of Western strategic concerns—foremost among them, the Cold War fear that Iran might fall into Soviet orbit if Mossadegh’s nationalist government, supported by the left-leaning Tudeh Party, were allowed to continue unchecked.27 British motives were more economic: they sought to reclaim control over Iranian oil after Mossadegh’s nationalization of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company. Thus, national sovereignty collided with Cold War realpolitik and imperial interests in a fateful alignment.

The initial phase of the operation was riddled with uncertainty. The CIA’s Kermit Roosevelt Jr., grandson of President Theodore Roosevelt, led the mission on the ground in Tehran. The plan was to pressure the Shah to dismiss Mossadegh and appoint General Fazlollah Zahedi as the new prime minister, backed by a mix of royalist officers, tribal allies, and street agitators.28 On August 15, the first attempt to oust Mossadegh failed when the prime minister, having been tipped off, had the officers involved in the plot arrested. The Shah, terrified of the unfolding events, fled to Baghdad and then to Rome, believing his rule was over. However, rather than extinguishing the coup, this temporary failure galvanized the CIA and their Iranian collaborators to regroup. Over the next four days, they funneled money into street protests, bribed newspaper editors, and mobilized mobs—including criminal gangs such as those led by Shaban Jafari (“Shaban the Brainless”)—to create the appearance of popular unrest and support for the Shah.

On August 19, 1953, the streets of Tehran erupted in violence and chaos. Orchestrated demonstrations culminated in clashes around government buildings, with army units loyal to the coup taking control of key locations. With the military now firmly aligned against Mossadegh, his residence was attacked and he was arrested by nightfall. Zahedi emerged as the new prime minister, and the Shah triumphantly returned to Iran within days, heralded as the savior of the nation.29 In the wake of the coup, Mossadegh was tried for treason, sentenced to house arrest, and silenced from public life. Many of his allies were imprisoned, exiled, or executed, and the National Front was suppressed. The Tudeh Party was dismantled with ruthless efficiency, its members hunted down and its influence extinguished. The monarchy, previously restrained by constitutional checks, was now resurrected as an absolute institution, backed by foreign intelligence and military support.

The success of the coup emboldened the Shah and transformed the Iranian political landscape for decades. It ushered in a period of autocratic rule characterized by the consolidation of royal authority, the expansion of the secret police (SAVAK), and a foreign policy closely aligned with U.S. strategic interests. For the United States, the coup was initially celebrated as a triumph of covert intervention, forestalling perceived Soviet encroachment and securing Western access to Iranian oil. In reality, it marked the beginning of deep mistrust between the Iranian populace and the West, particularly toward the United States, whose role in toppling a democratically elected leader was perceived as betrayal of Iran’s national aspirations.30 The Shah’s regime, bolstered by petrodollars and U.S. military aid, became increasingly authoritarian, setting the stage for the revolutionary backlash of 1979. Thus, what appeared in 1953 as a tactical victory proved to be a strategic blunder with long-term repercussions.

The legacy of the 1953 coup endures as a foundational trauma in the Iranian national consciousness. For many Iranians, the event came to symbolize the thwarting of Iran’s potential for democratic development and the cynical manipulation of the country by foreign powers. Declassified U.S. government documents in recent decades have confirmed the details of CIA involvement, adding historical validation to long-held Iranian suspicions. The coup has also become a reference point in broader debates about sovereignty, imperialism, and the ethics of foreign intervention in the postcolonial world. As historian Ervand Abrahamian has noted, the memory of 1953 is inseparable from the grievances that fueled the Islamic Revolution, animating calls for independence and resistance against external domination.31 The fall of Mossadegh was not merely the end of a government—it was the closure of a chapter in Iran’s pursuit of modern constitutionalism, one that continues to cast a shadow over its political imagination.

Conclusion

The period from the Qajar ascension to the 1953 coup illustrates the core dilemmas of modern Iranian history: the tension between reform and tradition, nationalism and imperialism, monarchy and democracy. It is a story of aspirations deferred and sovereignty compromised. The failure of constitutionalism, the rise of authoritarian modernization, and the foreign-orchestrated coup laid the foundation for decades of political repression and revolutionary backlash. Iran’s 20th-century trajectory cannot be understood without reckoning with this pivotal epoch—when dreams of democracy contended with the realities of empire and oil.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Abbas Amanat, Iran: A Modern History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017), 211–214.

- Firuz Kazemzadeh, Russia and Britain in Persia, 1864–1914: A Study in Imperialism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1968), 12–19.

- Nikki R. Keddie, Modern Iran: Roots and Results of Revolution (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006), 25–30.

- Homa Katouzian, State and Society in Iran: The Eclipse of the Qajars and the Emergence of the Pahlavis (London: I.B. Tauris, 2000), 61–65.

- Mangol Bayat, Iran’s First Revolution: Shi’ism and the Constitutional Revolution of 1905–1909 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 110–117.

- Ervand Abrahamian, A History of Modern Iran (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 32–36.

- Abrahamian, A History of Modern Iran, 19-21.

- Bayat, Iran’s First Revolution, 143-147.

- Katouzian, State and Society in Iran, 75-79.

- Amanat, Iran, 422-426.

- Vanessa Martin, Islam and Modernism: The Iranian Revolution of 1906 (London: I.B. Tauris, 1989), 196–199.

- Abrahamian, A History of Modern Iran, 36-39.

- Amanat, Iran, 440-443.

- Katouzian, State and Society in Iran, 97-101.

- Stephanie Cronin, The Army and the Creation of the Pahlavi State in Iran, 1921–1926 (London: I.B. Tauris, 1997), 154–157.

- Keddie, Modern Iran, 58-61.

- Katouzian, State and Society in Iran, 107-110.

- Amanat, Iran, 472-476.

- Abrahamian, A History of Modern Iran, 67-69.

- Stephanie Cronin, Reformers and Revolutionaries in Modern Iran: New Perspectives on the Iranian Left (London: Routledge, 2004), 92–94.

- Roham Alvandi, Nixon, Kissinger, and the Shah: The United States and Iran in the Cold War (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 11–13.

- Abrahamian, A History of Modern Iran, 80-83.

- Homa Katouzian, Mossadegh and the Struggle for Power in Iran (London: I.B. Tauris, 1990), 105–109.

- Amanat, Iran, 511-515.

- Stephen Kinzer, All the Shah’s Men: An American Coup and the Roots of Middle East Terror (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2003), 164–176.

- Ali Rahnema, Behind the 1953 Coup in Iran: Thugs, Turncoats, Soldiers, and Spooks (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 302–305.

- Ervand Abrahamian, The Coup: 1953, the CIA, and the Roots of Modern U.S.–Iranian Relations (New York: The New Press, 2013), 5–9.

- Kinzer, All the Shah’s Men, 130-145.

- Amanat, Iran, 525-530.

- Mark J. Gasiorowski, “The 1953 Coup D’État in Iran,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 19, no. 3 (1987): 261–286.

- Abrahamian, A History of Modern Iran, 100-104.

Bibliography

- Abrahamian, Ervand. The Coup: 1953, the CIA, and the Roots of Modern U.S.–Iranian Relations. New York: The New Press, 2013.

- —-. A History of Modern Iran. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Alvandi, Roham. Nixon, Kissinger, and the Shah: The United States and Iran in the Cold War. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Amanat, Abbas. Iran: A Modern History. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017.

- Bayat, Mangol. Iran’s First Revolution: Shi’ism and the Constitutional Revolution of 1905–1909. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

- Cronin, Stephanie. Reformers and Revolutionaries in Modern Iran: New Perspectives on the Iranian Left. London: Routledge, 2004.

- —-. The Army and the Creation of the Pahlavi State in Iran, 1921–1926. London: I.B. Tauris, 1997.

- Gasiorowski, Mark J. “The 1953 Coup D’État in Iran.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 19, no. 3 (1987): 261–286.

- Kazemzadeh, Firuz. Russia and Britain in Persia, 1864–1914: A Study in Imperialism. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1968.

- Katouzian, Homa. Mossadegh and the Struggle for Power in Iran. London: I.B. Tauris, 1990.

- —-. State and Society in Iran: The Eclipse of the Qajars and the Emergence of the Pahlavis. London: I.B. Tauris, 2000.

- Keddie, Nikki R. Modern Iran: Roots and Results of Revolution. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006.

- Kinzer, Stephen. All the Shah’s Men: An American Coup and the Roots of Middle East Terror. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2003.

- Martin, Vanessa. Islam and Modernism: The Iranian Revolution of 1906. London: I.B. Tauris, 1989.

- Rahnema, Ali. Behind the 1953 Coup in Iran: Thugs, Turncoats, Soldiers, and Spooks. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Originally published by Brewminate, 06.23.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.