Fletcherism’s legacy is not merely that of a peculiar dietary eccentricity but of a revealing moment in the history of food, science, and self-control.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Appetite, Discipline, and the Modern Body

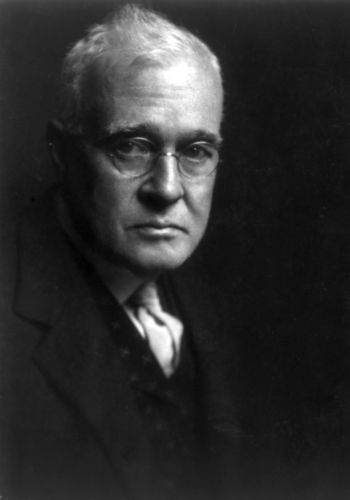

In the final years of the nineteenth century, as industrial modernity reshaped the rhythms of American life, the nation found itself preoccupied with the problem of health and diet. Urbanization and mechanization had not only changed the pace of work but also the pace of eating. Against this backdrop, Horace Fletcher emerged as a curious prophet of mastication. Known popularly as “The Great Masticator,” Fletcher promoted a regimen of slow, deliberate chewing, in which each bite of food was ground by the teeth up to one hundred times before swallowing. His method, quickly dubbed “Fletcherism,” promised not simply weight loss but moral and physiological transformation. Fletcher himself claimed to have shed nearly forty pounds through this practice, and he traveled the world to spread what he framed as a scientifically proven gospel of eating.1

The Origins of Fletcherism

Fletcher’s approach emerged in an era when scientific dietetics was still in its infancy, yet increasingly entangled with moral ideals of self-control. Born in 1849, Fletcher came to his dietary convictions later in life, after personal struggles with health and employment left him searching for a remedy to both physical and professional stagnation.2 His discovery of mastication as the key to health was not the product of formal medical training but of personal experimentation. He insisted that food should be chewed until it became fluid, swallowed only when the body “swallowed itself,” a phrase meant to indicate the natural reflexive urge once the food was sufficiently liquefied.3

The discipline extended beyond the act of chewing. Fletcher counseled his followers never to eat until they were “good and hungry” and never to eat when angry or anxious. To do otherwise, he argued, was to betray the body’s natural rhythms and invite illness. In this respect, Fletcherism was as much a philosophy of self-governance as it was a nutritional theory, aligning with a Progressive Era belief that the management of one’s habits could reform the self and, by extension, society.4

The Practice and Its Promises

Perhaps the most striking aspect of Fletcherism was its allowance for unrestricted food choice. Followers could consume anything they desired (meat, sweets, or otherwise) so long as they chewed it with sufficient thoroughness. The process, Fletcher promised, would naturally limit consumption by making overeating physically tedious. The result, according to Fletcher, was a leaner body, improved digestion, and a remarkable transformation of bodily waste. He famously claimed that true adherents would defecate only once every two weeks, producing nearly odorless excrement. In what can only be described as a feat of promotional eccentricity, Fletcher even carried a sample of his own stool in a sealed jar to lectures as proof of his claims.5

While the scatological centerpiece of Fletcherism’s marketing struck many contemporaries as bizarre, it was not without precedent in the era’s fascination with bodily regularity and elimination. The late nineteenth century witnessed an upsurge of interest in colon health, purgatives, and dietary fiber, and Fletcher’s assertions, though unorthodox, were framed as part of a broader hygienic project.6

Fletcherism and Scientific Reception

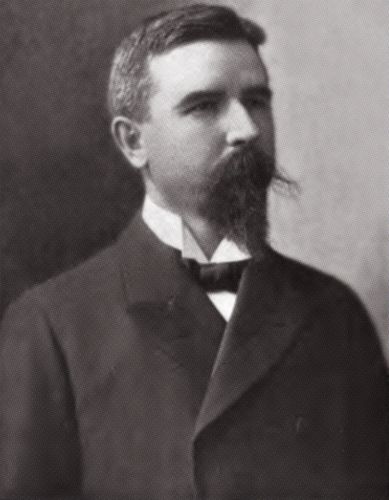

Fletcher was more than a showman. His ideas attracted the interest of prominent scientists and physicians of his day, including Yale physiologist Russell Henry Chittenden, who conducted controlled studies on Fletcher’s chewing regimen with military recruits and athletes. The results, while mixed, suggested potential benefits in nutrient absorption and reduced food waste.7 This partial endorsement from the scientific community lent Fletcherism a veneer of legitimacy, even if many doctors remained skeptical of its more extravagant claims.

Fletcher also capitalized on the rising prestige of laboratory science, presenting himself not as a crank but as a pioneer in nutritional research. He adopted the language of metabolism and caloric efficiency, linking his method to measurable outcomes. Yet his emphasis on extreme mastication went beyond the scope of empirical support, sliding into a quasi-spiritual ritual that blurred the lines between science and moral exhortation.8

Cultural Impact and Decline

By the early twentieth century, Fletcherism had become a minor dietary craze, finding adherents not only in the United States but also in Britain and continental Europe. Its appeal lay partly in its compatibility with existing habits, one could still enjoy indulgent foods, and partly in its alignment with the era’s fascination with bodily discipline. Fletcher’s lecture tours drew curious crowds, and his books sold widely.

However, as nutritional science advanced in the 1910s and 1920s, Fletcherism began to wane. Caloric science, vitamin research, and the standardization of dietary recommendations shifted the conversation away from mastication as the central determinant of health. Fletcher’s death in 1919 removed the charismatic force behind the movement, and without his tireless promotion, Fletcherism faded into a historical curiosity.9

Conclusion: The Aftertaste of a Dietary Fad

Fletcherism’s legacy is not merely that of a peculiar dietary eccentricity but of a revealing moment in the history of food, science, and self-control. In its insistence on slowing the act of eating, it anticipated later research on the relationship between eating speed and satiety, though without the exaggerated prescriptions that made Fletcher a figure of both fascination and ridicule. His blending of personal testimony, selective scientific validation, and moral instruction captures the spirit of Progressive Era health reform, when the line between bodily care and moral character was often indistinct. Fletcher’s life and work remind us that the history of diet is as much about cultural values as it is about nutritional science, and that the act of eating has long been a site where physiology, identity, and self-discipline intersect.10

Appendix

Footnotes

- Horace Fletcher, The A.B.-Z. of Our Own Nutrition (New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1903), 15–17.

- Louise Foxcroft, Calories and Corsets: A History of Dieting Over Two Thousand Years (London: Profile Books, 2012), 174–176.

- Fletcher, The New Glutton or Epicure (London: Grant Richards, 1911), 54.

- Foxcroft, Calories and Corsets, 179.

- Ibid., 181.

- Harvey Levenstein, Revolution at the Table: The Transformation of the American Diet (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 106–107.

- Russell Henry Chittenden, Physiological Economy in Nutrition (New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1904), 213–218.

- Ibid., 225.

- Levenstein, Revolution at the Table, 108.

- Foxcroft, Calories and Corsets, 182–183.

Bibliography

- Chittenden, Russell Henry. Physiological Economy in Nutrition. New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1904.

- Fletcher, Horace. The A.B.-Z. of Our Own Nutrition. New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1903.

- ———. The New Glutton or Epicure. London: Grant Richards, 1911.

- Foxcroft, Louise. Calories and Corsets: A History of Dieting Over Two Thousand Years. London: Profile Books, 2012.

- Levenstein, Harvey. Revolution at the Table: The Transformation of the American Diet. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.14.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.