Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Established by the United States Constitution, the Supreme Court began to take shape with the passage of the Judiciary Act of 1789 and has enjoyed a rich history since its first assembly in 1790. The Supreme Court is deeply tied to its traditions: Of the federal government’s three branches, the Court bears the closest resemblance to its original form – a 225 year old legacy.

The Court as an Institution

The Constitution elaborated neither the exact powers and prerogatives of the Supreme Court nor the organization of the Judicial Branch as a whole. Thus, it was left to Congress and to the Justices of the Court through their decisions to develop the Federal Judiciary and a body of Federal law.

The establishment of a Federal Judiciary was a high priority for the new government, and the first bill introduced in the United States Senate became the Judiciary Act of 1789. The act divided the country into 13 judicial districts, which were, in turn, organized into three circuits: the Eastern, Middle, and Southern. The Supreme Court, the country’s highest judicial tribunal, was to sit in the Nation’s Capital, and was initially composed of a Chief Justice and five Associate Justices. For the first 101 years of the Supreme Court’s life — but for a brief period in the early 1800’s — the Justices were also required to “ride circuit,” and hold circuit court twice a year in each judicial district.

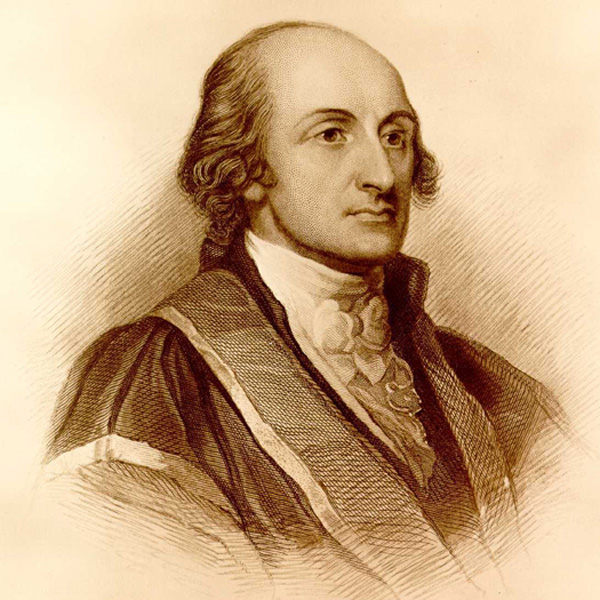

The Supreme Court first assembled on February 1, 1790, in the Merchants Exchange Building in New York City — then the Nation’s Capital. Chief Justice John Jay was, however, forced to postpone the initial meeting of the Court until the next day since, due to transportation problems, some of the Justices were not able to reach New York until February 2.

The earliest sessions of the Court were devoted to organizational proceedings. The first cases reached the Supreme Court during its second year, and the Justices handed down their first opinion on August 3, 1791 in the case of West v. Barnes.

During its first decade of existence, the Supreme Court rendered some significant decisions and established lasting precedents. However, the first Justices complained of the Court’s limited stature; they were also concerned about the burdens of “riding circuit” under primitive travel conditions. Chief Justice John Jay resigned from the Court in 1795 to become Governor of New York and, despite the pleading of President John Adams, could not be persuaded to accept reappointment as Chief Justice when the post again became vacant in 1800.

Consequently, shortly before being succeeded in the White House by Thomas Jefferson, President Adams appointed John Marshall of Virginia to be the fourth Chief Justice. This appointment was to have a significant and lasting effect on the Court and the country. Chief Justice Marshall’s vigorous and able leadership in the formative years of the Court was central to the development of its prominent role in American government. Although his immediate predecessors had served only briefly, Marshall remained on the Court for 34 years and five months and several of his colleagues served for more than 20 years.

Members of the Supreme Court are appointed by the President subject to the approval of the Senate. To ensure an independent Judiciary and to protect judges from partisan pressures, the Constitution provides that judges serve during “good Behaviour,” which has generally meant life terms. To further assure their independence, the Constitution provides that judges’ salaries may not be diminished while they are in office.

The number of Justices on the Supreme Court changed six times before settling at the present total of nine in 1869. Since the formation of the Court in 1790, there have been only 17 Chief Justices and 102 Associate Justices, with Justices serving for an average of 16 years. Since five Chief Justices had previously served as Associate Justices, there have been 114 Justices in all. This included former Justice John Rutledge, who was appointed Chief Justice under an interim commission during a recess of Congress and served for only four months in 1795. When the Senate failed to confirm him, his nomination was withdrawn; however, since he held the office and performed the judicial duties of Chief Justice, he is properly regarded as an incumbent of that office.

Despite this important institutional continuity, the Court has had periodic infusions of new Justices and new ideas throughout its existence; on average a new Justice joins the Court almost every two years. President Washington appointed the six original Justices and before the end of his second term had appointed four other Justices. During his long tenure, President Franklin D. Roosevelt came close to this record by appointing eight Justices and elevating Justice Harlan Fiske Stone to be Chief Justice.

The Court and Its Traditions

For all of the changes in its history, the Supreme Court has retained so many traditions that it is in many respects the same institution that first met in 1790, prompting one legal historian to call it, “the first Court still sitting.”

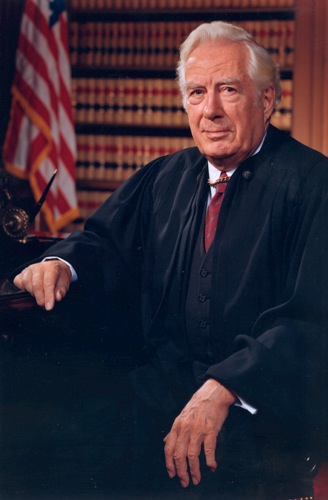

Justices have perpetuated the tradition of longevity of tenure. Recently, Justice John Paul Stevens served for 34 years before retiring in 2010 as the fourth longest serving Justice in the Court’s history, just barely missing the third longest record of service held by Justice Hugo Black, who served for 34 years and one month prior to his retirement in 1971. The record for length of service is held by Justice William O. Douglas, who retired on November 12, 1975, after serving a total of 36 years and six months. He surpassed the previously held record of Justice Stephen J. Field, who served for 34 years and six months from 1863 to 1897.

As is customary in American courts, the nine Justices are seated by seniority on the Bench. The Chief Justice occupies the center chair; the senior Associate Justice sits to his right, the second senior to his left, and so on, alternating right and left by seniority.

Since at least 1800, it has been traditional for Justices to wear black robes while in Court. Chief Justice Jay, and apparently his colleagues, lent a colorful air to the earlier sessions by wearing robes with a red facing, somewhat like those worn by early colonial and English judges. The Jay robe of black and salmon is now in the possession of the Smithsonian Institution.

Initially, all attorneys wore formal “morning clothes” when appearing before the Court. Senator George Wharton Pepper of Pennsylvania often told friends of the incident he provoked when, as a young lawyer in the 1890s, he arrived to argue a case in “street clothes.” Justice Horace Gray was overheard whispering to a colleague, “Who is that beast who dares to come in here with a grey coat?” The young attorney was refused admission until he borrowed a “morning coat.” Today, the tradition of formal dress is followed only by Department of Justice and other government lawyers, who serve as advocates for the United States Government.

Quill pens have remained part of the Courtroom scene. White quills are placed on counsel tables each day that the Court sits, as was done at the earliest sessions of the Court. The “Judicial Handshake” has been a tradition since the days of Chief Justice Melville W. Fuller in the late 19th century. When the Justices assemble to go on the Bench each day and at the beginning of the private Conferences at which they discuss decisions, each Justice shakes hands with each of the other eight. Chief Justice Fuller instituted the practice as a reminder that differences of opinion on the Court did not preclude overall harmony of purpose.

The Supreme Court has a traditional seal, which is similar to the Great Seal of the United States, but which has a single star beneath the eagle’s claws— symbolizing the Constitution’s creation of “one Supreme Court.” The Seal of the Supreme Court of the United States is kept in the custody of the Clerk of the Court and is stamped on official papers, such as certificates given to attorneys newly admitted to practice before the Supreme Court. The seal now used is the fifth in the Court’s history.

Oaths of Office

Overview

The Constitution provides that the President “shall nominate, and by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, shall appoint…judges of the Supreme Court….” After Senate confirmation, the President signs a commission appointing the nominee, who then must take two oaths before executing the duties of the office. These oaths are known as the Constitutional Oath and the Judicial Oath.

The Constitutional Oath

As noted below in Article VI, all federal officials must take an oath in support of the Constitution:

“The Senators and Representatives before mentioned, and the Members of the several State Legislatures, and all executive and judicial Officers, both of the United States and of the several States, shall be bound by Oath or Affirmation, to support this Constitution; but no religious Test shall ever be required as a Qualification to any Office or public Trust under the United States.”

The Constitution does not provide the wording for this oath, leaving that to the determination of Congress. From 1789 until 1861, this oath was, “I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will support the Constitution of the United States.” During the 1860s, this oath was altered several times before Congress settled on the text used today, which is set out at 5 U. S. C. § 3331. This oath is now taken by all federal employees, other than the President:

“I, _________, do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same; that I take this obligation freely, without any mental reservation or purpose of evasion; and that I will well and faithfully discharge the duties of the office on which I am about to enter. So help me God.”

The Judicial Oath

The origin of the second oath is found in the Judiciary Act of 1789, which reads “the justices of the Supreme Court, and the district judges, before they proceed to execute the duties of their respective offices” to take a second oath or affirmation. From 1789 to 1990, the original text used for this oath (1 Stat. 76 § 8) was:

“I, _________, do solemnly swear or affirm that I will administer justice without respect to persons, and do equal right to the poor and to the rich, and that I will faithfully and impartially discharge and perform all the duties incumbent upon me as _________, according to the best of my abilities and understanding, agreeably to the constitution and laws of the United States. So help me God.”

In December 1990, the Judicial Improvements Act of 1990 replaced the phrase “according to the best of my abilities and understanding, agreeably to the Constitution” with “under the Constitution.” The revised Judicial Oath, found at 28 U. S. C. § 453, reads:

“I, _________, do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will administer justice without respect to persons, and do equal right to the poor and to the rich, and that I will faithfully and impartially discharge and perform all the duties incumbent upon me as _________ under the Constitution and laws of the United States. So help me God.”

The Combined Oath

Upon occasion, appointees to the Supreme Court have taken a combined version of the two oaths, which reads:

“I, _________, do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will administer justice without respect to persons, and do equal right to the poor and to the rich, and that I will faithfully and impartially discharge and perform all the duties incumbent upon me as _________ under the Constitution and laws of the United States; and that I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same; that I take this obligation freely, without any mental reservation or purpose of evasion; and that I will well and faithfully discharge the duties of the office on which I am about to enter. So help me God.”

Administration of the Oaths of Office

Neither the Constitution nor the Judiciary Act of 1789 specified the manner of administration of the oaths. William Cushing, one of the first five Associate Justices, wrote to the first Chief Justice, John Jay, asking for guidance as to who should administer the oaths. Jay replied, “No particular person being designated by Law, to administer to us the oaths prescribed by the Statute, I thought it best to take them before the Chief Justice of this state [New York].” While Cushing must have eventually taken his oaths as an Associate Justice, no documentation has been located recording who administered them. Other early members of the Court took their oaths before various government officials. For example, James Wilson took his in 1789 before Samuel Powell, the Mayor of Philadelphia.

The early Justices were required to sit on regional circuit courts in addition to their duties on the Supreme Court. If a Justice had not taken the oaths of office locally upon receipt of his commission, he would do so on arrival at the circuit court. The presiding judge or clerk of the court would administer the oaths and endorse the back of the Justice’s commission, testifying that the oaths had been taken as prescribed by law. When the new Justice first sat with the Supreme Court, he would present his commission, which would be read aloud in open court and recorded in the Court’s Minutes. If the Justice had not yet taken the oaths, they would be administered.

Two Oath Ceremonies Evolve

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, as Supreme Court Terms grew longer and circuit court duties diminished, new appointees were more likely to begin their work with the Supreme Court in Washington, D.C. Two distinct oath ceremonies developed. In the first, the Chief Justice or the senior Associate Justice administered the Constitutional Oath during a private ceremony, usually held in the Justices’ Consultation Room in the U.S. Capitol. In the second, the Clerk read the commission in open court and administered the Judicial Oath before the new Justice took his seat on the Bench.

For the most part, this process was followed until 1940 when President Franklin D. Roosevelt invited Frank Murphy to take his Constitutional Oath at the White House. On January 18th, Murphy’s Constitutional Oath was administered in the Oval Office by Justice Stanley F. Reed as the President looked on. A newspaper covering the event stated this occurrence was “without precedent.” A little more than two weeks later, on February 5, 1940, the Clerk of the Supreme Court administered the Judicial Oath to Murphy in the Courtroom and the new Justice took his seat.

By the 1950s, the practice of administering the oaths at the Supreme Court Building resumed. If the new Justice had not previously taken the oaths, the Chief Justice or senior Associate Justice administered the Constitutional Oath privately in the Justices’ Conference Room after which the Justices proceeded to the Courtroom. Upon entering, the new Justice sat near the Clerk of the Court while the Clerk read the commission aloud. Next, the Clerk administered the Judicial Oath and the new Justice took the Bench. If the oaths had already been taken, the new Justice sat at the Bench upon entering and the Chief Justice simply announced the change in membership.

The Investiture Ceremony

On June 23, 1969, the Court closed its last scheduled sitting with a formal Courtroom ceremony in which retiring Chief Justice Earl Warren administered a combined oath to incoming Chief Justice Warren E. Burger. Under Chief Justice Burger, the Court began to hold special sittings to receive the commissions of newly appointed Justices. The first ceremony of this kind was held for Justice Harry A. Blackmun on June 9, 1970. During this special ceremony, referred to as the investiture, the Chief Justice generally administers the Constitutional Oath privately to the new Justice in the Justices’ Conference Room, the commission is presented and read aloud in the Courtroom and the Chief Justice administers the Judicial Oath in the Courtroom. Burger also started a tradition of having the new Justice sit in the historic John Marshall Bench Chair at the beginning of the ceremony.

More Recent Changes

In 1986, President Ronald Reagan revived the practice of holding a Constitutional Oath ceremony at the White House when he hosted a ceremony for Chief Justice-designate William H. Rehnquist and Justice-designate Antonin Scalia. Retiring Chief Justice Warren E. Burger administered the Constitutional Oaths to both after which Rehnquist said, “At the conclusion of the second part of these proceedings in our Court this afternoon, I will become the sixteenth Chief Justice of the United States.” Later that day in a special sitting in the Courtroom, Chief Justice Burger administered the Judicial Oath to Rehnquist. Chief Justice Rehnquist in turn administered the Judicial Oath to Scalia, making Scalia the only Justice to take oaths from two different Chief Justices on the same day.

Subsequently, some oaths have been taken at the White House, or other locations as circumstances may dictate. For example, Stephen G. Breyer, confirmed during the summer of 1994, was vacationing near Chief Justice Rehnquist. Rather than wait to take the oaths, he drove to Rehnquist’s location in Vermont where the Chief Justice administered them. When all had returned to Washington, D.C., Breyer retook the Constitutional Oath at a White House ceremony and an investiture ceremony was also held at the Supreme Court on September 30, 1994.

In 2009, the Supreme Court broadcast an oath taking ceremony from the Supreme Court Building for the first time. After Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr., privately administered the Constitutional Oath to Justice Sonia Sotomayor in the Justices’ Conference Room, her Judicial Oath ceremony was broadcast live from the East Conference Room. A year later, Justice Elena Kagan took the oaths in a similar sequence at the Court, again broadcast live.

Originally published by The Supreme Court of the United States to the public domain.