The widespread influence of the idea of ancient Rome on political rhetoric.

By Dr. Cosimo Cascione

Professor of Roman Law and the Foundations of European Law

Department of Jurisprudence

Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II

Introduction

Studies on the relationship between fascism and law have multiplied in recent years (Lacchè 2015; Birocchi and Loschiavo 2015; Stolzi 2014; Montagnani 2012).1 Yet the specific relationship between the policies of the fascist regime and Roman law (more in general the history of law) still appears only partially explored.2 The point is that this is a multiform matter. It clearly touches the adherence to fascism by individual professors of the discipline, as well as a series of links that during two decades of totalitarian power emerged between Roman law (a legal system which carries the motives of tradition and order) and the ideology of the dominant policy at the time. The laws of the ancient Romans were proposed as an ideal, a model for the present (not a new idea, indeed, but in a new context). Here I would like to put in evidence at least one of these links, that is, the widespread influence of the idea of ancient Rome on the regime’s political rhetoric and how that idea also played a role in reconstructing a connection with Roman law considered as a genetic factor of the fascist legal order.

An Encyclopaedia Entry: The Idea of Rome

A useful observation point from which to regard the idea of Rome during the fascist era could be one of the most important cultural enterprises of the regime, namely the Enciclopedia Italiana di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti, better known as Enciclopedia Treccani, after the name of its initiator, Giovanni Treccani (1877‒1961), a businessman and patron of many significant intellectual initiatives in those days. It is the Enciclopedia and two of its entries, ‘Rome’ and ‘Fascism’ (in this perspective ‘law’ is of lesser importance),3 which form the starting points of this brief reflection on fascist Roman law.

The director of Enciclopedia Treccani was the neo-Hegelian idealist philosopher and politician Giovanni Gentile (1875‒1944), who is usually called the ‘philosopher of fascism’ (Gregor 2001). This major work was first published between 1929 and 1936 in thirty-five volumes (plus one index volume). In this magnum opus great importance is dedicated to classical antiquity (Cagnetta 1990). Roman history forms the very centre, the core, of the Enciclopedia, and of course Roman law (with its tradition in the Middle Ages and in the modern era) has its proper place. This is not unusual, considering that, from the beginning of his political movement, Mussolini had stressed the common Roman heritage of Italians, and he fervently wished to restore the former glory of the Romans in Italy and indeed the world (Giardina 2008; cf. Giardina and Vouchez 2000: 212‒86).

The strategic choices made by Gentile in assigning roles of direction within the enterprise and the individual entries were clearly generally, though not always, aligned with the policy of the regime. Gentile was inspired by what has been called ‘lucky double dealing’ (Cagnetta 1990: 11): He attracted not only fascist intellectuals. In the section dedicated to classics, former neutralists and Germanophiles, such as the great historian Gaetano De Sanctis (1870‒1957), well known as an anti-fascist,4 and the authoritative philologist Giorgio Pasquali (1885‒1952), very close to German culture since his studies at Göttingen, were involved, and the direction of the section on law was given to the Romanist Pietro Bonfante (1864‒1932),5 who some years earlier had engaged in a fierce polemic against the same Gentile and the other great representative of Italian idealist philosophy, Benedetto Croce (1866‒1954), which ended up almost in mutual insult.6

In the Enciclopedia Italiana, the entry ‘Roma’ was particularly significant.7 The part devoted to the ‘idea of Rome’8 – assigned to Pasquali – shows two perspectives in the history of the classical tradition: the idea as contained in ancient writings and a matching construction of the myth of Rome. These perceptions are intertwined, but the myth is clearly more useful to politics than an erudite scholarly historical treatment of sources and related bibliography. The use (or abuse) of Roman-ness (Italian Romanità) (cf. Arthurs 2012, with Chiari 2013: 1; Nelis 2013) had been a typical political tool of trends in Italian nationalism since the Middle Ages.9 Rome was one of the principal aims of the Italian Risorgimento: the political unification of the Italian peninsula took on a new meaning with the seizure of the city in 1870, a sense of continuity with ancient grandeur (cf. Gramsci 1975a: 971).

An anecdote, a dictum of the great German historian and jurist Theodor Mommsen (1818‒1903), reveals a common feeling among European intellectuals. Mommsen once asked Quintino Sella, Italian minister of finance (1827‒84), a ‘spirited’ (Chabod 1996: 155) question: ‘What do you intend to do in Rome? This is worrying all of us: it is impossible to stay in Rome without cosmopolitan purposes’ (Sella 1887: 292).10 Mommsen’s view was, of course, influenced by his evaluation of the universal role of Roman law as well as by consideration of the millenarian mission of the Roman Catholic Church, whose temporal power had just been abolished by the Italian government. The universal idea of Rome existed over and above its mere existence as an Italian city (and the new capital of the realm, after Turin and Florence).

The great innovation of fascist attitudes towards this myth was its diffusion in a global dimension (not only among the educated classes), which led to the rhetorically simple equation of Italians as contemporary Romans: a significant new political implication of the masses. Anyone could understand the meaning of the Roman military force (especially the veterans of the First World War), even without being able to understand a poem by Ovid or Catullus, to discuss a passage from Tacitus or to interpret a fragment of Roman law.

Indeed the ‘fascist sense of roman-ness could do without books’ (as it was written) (Giardina 2008: 63). However, books were aimed at nurturing a culture of glorification of the past and constantly setting connections with contemporary Italian life. Books offered, among other things, a messianic vision of Italy’s imperialist commitment in the Mediterranean (the ancient Mare nostrum) and especially in Africa. Fascist culture is not only ‘printed’ but also expressed in rituals, celebrations, images, art and architecture (spread across the media: radio, newspapers and cinema), constantly referring to the myth of Rome. This is not always the historic Rome: Sometimes it is only a shadow or a distorted projection of that reality.

The Roman model was immediately clear in the symbolism of fascism: the very name of the party has Roman roots (Giardina and Vouchez 2000: 224ff ). Fascism derives from the fasces, rod-bundles used by the lictores (auxiliaries preceding magistrates) to drive away the masses and able to carry out violent coercion against those who disobeyed the orders of their superiors (cf. Mommsen 1887: 373): Fasceswere weaponized with an axe when the magistrate was holder of the power of life and death. Thus the name recalls at the same time violence, unity of force and, according to Mussolini, even justice.11 Besides, the fascist salute (right arm raised with outstretched palm)12 corresponded to the Roman (also Greek) iconographic repertory (cf. Hug 1920: col. 2065), but in more recent times was used by the ‘legionnaires’ (another Roman retrieval) of the poet and military leader Gabriele D’Annunzio (1863‒1938) (cf. Falasca Zamponi 2003: 231ff ), who occupied the Istrian city of Fiume in 1919‒21 to protest the results of the Versailles peace treaty (corresponding to his idea of a ‘wingless victory’, which deprived Italy of the hope of acquiring territories formerly belonging to the Austro-Hungarian Empire).13

The Myth of the Good Old Roman (between Citizenship and Imperialism)

Mussolini strongly emphasized tradition and typical Roman features, such as military strength, courage, order and discipline, and glorified himself as the duce (Italian for the Latin dux), the leader. This identification of modern times with ancient models, based on a naive hereditary theory, was obsessively repeated and easily made extensible among the simplest people through mass communication. This revival of Roman greatness increased enthusiasm and interest not only in Italy but also abroad: It was a comforting model, made of order and composure (the Roman disciplina) in the agitated era after the First World War, when traditional societies (both conservative and liberal) felt threatened by the eastern monster of Bolshevism. The exaltation of this myth enabled the joinder of fascism with traditional conservative and nationalist political forces.

‘The myth of Rome was used by Mussolini, with a multiplicity of positive references, even before the fascist movement became a party’ (Giardina 2008: 55; cf. Giardina and Vouchez 2000: 238ff, and also Nelis 2012). Very soon he drew the relationship between fascism and Rome in a line that took the political centre of the movement along the two decades of its power, although there were not insignificant subsequent deviations. In fact, he said in a speech in 1922, some months before the March on Rome, on the occasion of Rome’s birthday (21 April,14 which for fascists and then for the ‘new’ fascist Italy replaced the celebrations for 1 May, socialist workers’ day):

As a matter of fact, Rome and Italy are two inseparable terms …. The Rome we honour is certainly not the Rome of the monuments and ruins, the Rome of the glorious ruins among which no civilized man walks without feeling a thrilling shiver of veneration …. The Rome we honour, but primarily the Rome we are longing for and planning is another one: it is not about honourable stones, but living souls: it is not the nostalgic contemplation of the past, but the hard preparation of the future. Rome is our starting point and reference; it is our symbol, or, if you will, our myth. We dream about a Roman Italy, that is, wise, strong, disciplined, imperial Italy. Much of what was the immortal spirit of Rome is reborn in fascism: the lictor is Roman, our organization of combat is Roman, our pride and our courage is Roman: Civis Romanus sum. (Mussolini 1956: 160f [1922: ix]; cf. Giardina and Vouchez 2000: 241ff )

Several political aspects of this discourse are relevant: the different aspects of the Roman tradition, the explicit reference to the lictors, especially the rhetorical affirmation of Roman citizenship in its Latin wording civis Romanus sum, stressing the identity-making representation.15

To a certain extent the statement was prophetic: After seizing power in 1924, in a solemn ceremony held in Campidoglio (in the Sala degli Orazi e Curiazi), again on 21 April, Mussolini obtained (modern) Roman citizenship. He could now also formally proclaim himself a Roman citizen (Mussolini 1956: 234–6 [1924: xi]), and he again used the Latin words. On that day ancient fascist Rome was born, and the project of the new fascist Rome proclaimed.

Mussolini declared the impenetrability of the Roman phenomenon merely by historical research. The actual fascist interpretation of the past rejects the slow elegance of philology: It could simply be action and intuition, also violence against the historical truth. The return to Roman-ness was a sort of ‘back to the future’ (Giardina and Vouchez 2000: 212f ),16 a pompous time-machine bringing the past into the present and connecting the future to the glory of the past with a political purpose that would be realized with the return of the Empire. Even though based on the past, this ideology was completely modern. It was of course a rhetorical exercise, but, at the same time, Realpolitik, practical politics.

As the years passed, Italians and the world perceived the stabilization of the tenth anniversary of the March on Rome (the powerful demonstration by which Mussolini came to power in October 1922). The revolutionary idea that had characterized the early days of the regime in 1932 was changed. It became more an imperial idea and took up the theme of the eternal destiny of Rome and its military power. In Italy, the war against Ethiopia (1935‒6), the enemy that had blocked Italian colonial enterprises in Eastern Africa at the end of the nineteenth century, and its subsequent conquest represented the moment of the greatest consensus for Mussolini and the regime. Many opponents aligned themselves with the expansionist policy that realized the old dream of an African Empire, reacting to the sanctions imposed by the League of Nations.17 On 9 May 1936, the Duce triumphantly proclaimed from the balcony of Palazzo Venezia ‘the reappearance of the empire over the fatal hills of Rome’ (Giardina and Vouchez 2000: 250ff ).18 The highest point of political support for Mussolini corresponded to the climax of the rhetoric of the myth of Rome. While Vittorio Emanuele, the King of Italy, also became emperor of Ethiopia, Mussolini reserved for himself the more expressive title of ‘founder of the Empire’ (cf. Calamandrei 2014: 93).

The asserted continuity was celebrated through a symbolic discontinuity: the transition in fascist rhetoric from the centrality of the character of Julius Caesar (the revolutionary dictator) to Augustus (the warrior but also the peacemaker and very Father of the Nation) (cf. Schieder 2016: 130ff ):19 both powerful ancient images that aimed to reflect (and enhance) the figure of the Duce. The Caesarian idea of a perpetual dictatorship (cf. De Martino 1973: 239ff ) enthused Mussolini, but he was a superstitious man: He feared the Ides of March (the notorious and symbolic date of the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 BC). At this stage, the Augustan idea of Rome, imperialism and the empire are perfectly combined in military and political action in Eastern Africa, then in Spain (beside the nationalist forces of Francisco Franco, 1936–9) and in the Albanian enterprise (militarily occupied by Italian forces and annexed in 1939).

Abusing the Past: Cosmopolitan Empire and Active Racism

What the regime concealed was the fact that the idea of Rome as reconstructed in the sources and the myth of the strong Roman citizen, rudis and pastorius (Flor. 2.2.4), as a depository of all the qualities, was a Utopia even in ancient Rome. It was an ideal type forged by the conservative party in the Catonian era.20

Between the 1920s and 1930s, the idea of Rome, then of the Roman Empire, became a political catalyst activated to gain consent. This strategy resumed (with adaptations) the Risorgimento’s themes of nationalism, irredentism (which had played a central role in Italy’s siding in the First World War and then in subsequent events as above mentioned concerning the Fiume enterprise), the expansionist drive in Africa, as cultural, propagandistic (and also military) activity in Europe. This idea was treading in the footsteps of the mythical ancient Roman man depicted, the builder of an orderly cosmopolis, fascist and totalitarian, based on the principle of authority (and at this point emerges the ideological role of Romanistic legal and institutional tradition) turned into hierarchy. But the imperial cosmopolis in the ancient world was not the result of alleged Roman purity. Regardless of the significant role of the various Italic tribes, the socii Italici or allies in ‘Roman’ military and economic expansionism, the important flow of ideas from East to West, based on advanced Hellenistic culture, cannot be ignored.

Between 1934 and 1935, locked up in prison for anti-fascist activities, Antonio Gramsci (1891‒1937) was able to develop a much deeper discourse that undermined the very idea of ‘Roman man’, showing how between the late Republic and early Principate, a kind of Roman arose, disconnected from the past:

It does not seem to be understood that Caesar and Augustus radically changed the position of Rome and of the peninsula in the balance of the classical world, removing Italy’s ‘territorial’ hegemony and transferring the function to a hegemonic imperial, i.e. supranational, class. If it is true that Caesar continues and concludes the democratic movement of the Gracchi, Marius, Catilina, it is also true that Caesar wins in the frame of the whole empire, while the problem for the Gracchi, for Marius, for Catilina arose so as to be solved in the peninsula, in Rome. This historical connection is of utmost importance for the history of the peninsula and of Rome, since it is the beginning of the process of ‘de-nationalization’ of Rome and of the peninsula and its becoming a ‘cosmopolitan’ territory. (Gramsci 1975b: 1959‒60)

The fascist regime built its representation of the relationship between Caesarian and Augustan policy (and between the two historical characters) more on intuition than on scientific grounds based on a serious confrontation with classical culture and its tradition. Gramsci, on the other hand, goes deeply into the comparison with historiography: From his thinking emerges a central venture to reconsider the imperial transition from the Roman Republic to the Principate:

The Roman aristocracy, which had, in the manner and by the means appropriate to the times, unified the peninsula and created a basis for national development, is overwhelmed by the imperial forces and the problems which it has raised: the historical-political knot is dissolved by Caesar with his sword and so a new era begins, in which the East has a weight so great that overcame the West and led to a rift between the two parts of the Empire. (Gramsci 1975b: 1959‒60)

Augustus wanted to legitimate the new world, an issue of the civil wars. A successful way to achieve this aim could be to rebuild the tradition, the moral connection, already partially lost, with the past. The literature genre of imperial epic (firstly Virgilius, with his Aeneid) performed this fundamental task. In the fascist reading there was no break in tradition: Roman man was a steady positive image.

At the end of the 1930s, in a political phase when fascism was much closer to Nazism and had borrowed its racist ideology, turning it into law in 1938,21 an extreme fascist fringe movement reused the mythical figure of the ideal Roman citizen to build the theory of ‘active racism’. This theory sought to provide a non-biological basis and identity for the ‘Italian race’. For Julius Evola (1898‒1974), the anti-egalitarian, anti-liberal, anti-democratic philosopher and esotericist (cf. Ferraresi 1988: 84), the central point of racism was not the blood theory, but the spiritual construction of a new man, ‘new’ but at the same time old. He wrote in 1941 (Evola 1994 [1941]: 155ff ) (on a theme already dealt by the author previously): ‘What better ideal model than the Roman man – stern, sober, active, free of expressionism, measured, calmly aware of his dignity?’ This model again retained from Roman times (or – better – from modern ideas of the ancient Roman) was to inspire the new Italian, but in an overall elitist vision of the fascist active man, remote from the masses: the multitasking abuse of the past.

Fascist Law: Tradition and Opportunism (an American Point of View and Another Encyclopaedia Entry)

In the phase of the consensus (1929‒36),22 fascism itself became a myth and (paradoxically in terms of logic) truth: the civilizing mission of Rome now stands alongside the ancient and the modern empire. The identification of past and present was seldom placed on a basis of serious historical analysis, as it was in the works of two fascist intellectuals, the historian Ettore Pais (1856‒1939) and the Romanist Pietro de Francisci (1883‒1971), who was rector of the University of Rome and then minister for justice. More often it was a superficial and ritual connection of past grandeur and (alleged) present glories. But the international context pushed the naive policy of Mussolini towards an unworthy and deadly embrace with Nazi Germany (which indeed had some anti-Roman founding traits, including in the field of law) (cf. Santucci 2009 and Vinci 2014).23

With respect to this vision of the idea of Rome, we should now look at the relationship between fascist policy and (Italian) law. In 1936 H. Arthur Steiner (1905‒91), who was then teaching at UCLA as an associate professor, one of the sharpest Anglophone interpreters of Italian political totalitarianism, wrote a theoretical essay entitled The Fascist Conception of Law, in which he provided a useful explanation of the cultural arguments that sought to provide a philosophical basis for fascist law (cf. Skinner 2015: 74). Steiner sees fascist law as a quid novi compared to the earlier Italian legal system:

Modern dictatorships, proceeding uniformly on the assumption that ‘the regime is precarious which has not begun by transforming the law and by investing it with its principles’, have sought to consolidate their positions behind a facade of distinctive legislation and juridical theory. Legal transformation not only insures the revolution, but actually makes it. (Steiner 1936: 1267)

His analysis highlights the transformations more than the continuity:

But to one who is given an opportunity to absorb the spirit of Fascist literature and legislation and to observe the phenomena of Fascism at first hand, inevitably comes a … conclusion: that Fascism represents, fundamentally, an entirely different conception of Society, Law, and State, and that from its philosophical assumptions are derived some elements of a universal and permanent character. (Steiner 1936: 1267)

The American scholar remarks here on the importance of the phenomenon and its spread in Europe (see Albanese 2016). At the same time he emphasizes the incomplete and unsystematic nature of legal fascism, as a result of political opportunism:

The striking expansion of Fascist thought in all of the countries of Western Europe suggests that its legal philosophy deserves careful study and analysis. It may be objected, at the outset, that Fascism should not be regarded as a complete philosophical system. For this doubt about its character, Fascists are themselves largely responsible. Fascist doctrine contains a substantial element of opportunism. (Steiner 1936: 1267)

This picture corresponds, to some extent, to the perspective that the Duce himself proposes in the entry on ‘Fascism’24 in the Enciclopedia Italiana (an article which owes much to the ideas of Giovanni Gentile). This, in 1932, was Mussolini’s first formal and complete (although not extensive) exposition of fascist thinking. In this view, tradition (especially Roman tradition) is the touchstone of the future:

‘Tradition is certainly one of the greatest spiritual forces of a people, inasmuch as it is a successive and constant creation of their soul.’ Respect for tradition as the custodian of the national soul must, however, be confined simply to the observance of profitable examples; it must not restrict or confine future development. Political doctrine must retain dynamism and versatility. There is a dose of opportunism in this recipe: ‘We do not believe in a single solution, be it economic, political or moral, a linear solution to the problems of life, because … life is not linear and can never be reduced to a segment traced by primordial needs’.

Historical-Legal Studies Taken Seriously and the Ornamental Antiquity: Roman Law between ‘Enciclopedia Italiana’ and the Civil Code of 1942

Arriving at this point arouses the curiosity to fathom the reading of Roman law in Treccani’s Enciclopedia. Only some mentions lie in the entry ‘Law’ (Diritto),25 which, however, does not contain a section specifically devoted to ‘Roman law’: We must once again be directed to the entry on ‘Rome’.

Anyone wishing to seek here explicit political traces and connections with the present would remain disappointed. This long essay is divided into four parts. The first – assigned to Emilio Albertario (1885‒1948), a fascist scholar, at the time a full professor of Roman law in Rome – is dedicated to private law and consists of a long, detailed discussion of sources and doctrines (in various fields of law, such as subject, object, legal transaction, family, property rights, obligations, inheritance, gift), oriented to a search for classical law, clearly separated from that of Justinian, strongly affected, in Albertario’s opinion, by interpolations and dogmatic errors (Albertario 1940).26 Roman public and criminal law were the subjects treated by Vincenzo Arangio-Ruiz (1884‒1964), an anti-fascist Romanist at that time teaching at the University of Naples, a signatory of the so-called Manifesto of anti-fascist intellectuals of 1925 (cf. Cascione 2009: 12ff ). Hunting for signs of acquiescence to the regime in his pages is needless: Even the coercive powers of the magistrates and the emperors are treated according to the best scientific standards, without any concession to comparison with the contemporary situation. The fourth part, devoted to the ius commune, was committed to Francesco Calasso (1904‒65), a historian of medieval (and modern) law. Despite emphatic expressions ‘great historical fact’ (grandioso fatto storico) and some abuse of superlatives27 (but it could be a question of style), the preparation of the contribution does not appear in any way influenced by the political context.

Analogously, it must be said that the entry on Fascismo signed by Mussolini contains no reference to Roman law (with the exception of the above-quoted phrase on the fasces): It is much more a philosophical frame than a legal one.

Back to the fascist idea of law: It represents a crude, eclectic, revolutionary political perspective in which the myth of tradition emerges as an ideological trinket, an ornament, but an important one, especially with regard to codification. This observation does not mean that this particular aspect of the Roman heritage did not play an important role in fascist use of legitimating tradition. The image of Roman law is strongly linked with order. It was the legal system of the Empire which the subjects of all nations must obey. At the same time it is one of the most enduring traditions of ancient Rome in modern times.

Many perspectives exist in which the specific relationship between fascism and Roman law can be re-read (cf. Cascione 2009: 3ff ): Three of these perspectives are – in my opinion – the most fruitful. They are strictly linked with three solid scientific personalities of Roman law scholarship of fascist times: the centrality of authority (auctoritas) in the Roman legal system (public and private) of de Francisci, put in parallel with the new fascist political constitution, the Romanism (the civilizing mission of Roman law in the ancient world as well as in later legal tradition) of Salvatore Riccobono (1864‒1958) and the modernization of a renewed social law proposed by Emilio Betti (1890‒1968) through dogmatics.28 All these interpretations gain strength from the relationship between past and present and form part of a nexus of continuity of long duration, where the fracture is represented by liberal Italy, the historical period prior to fascism. Conservation, reaction and revolution can thus be welded together without apparent contradiction. Even corporatism is tied to Roman history (as well as that of medieval towns) and the Roman–Italic spirit.

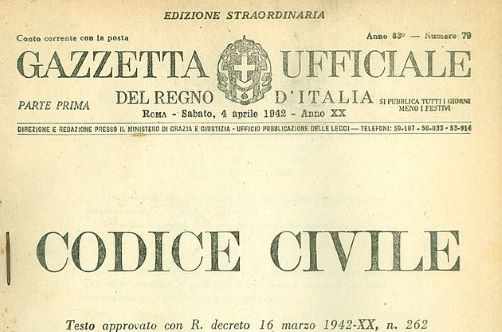

But, on these issues, I have already expressed my point of view in the contribution published in 2009 (Cascione 2009: 12ff ). Here I would like to look in a different direction, and that is the alleged continuity between Roman law (in particular classical Roman law) and the new codification of Italian civil and commercial law, that, after the preparatory works started in the 1920s (cf. Caprioli 2008: 131ff ), was completed with the entry into force of the Civil Code on 21 April (once again that fateful date) 1942, in the middle of the war (at a not unfavourable moment for Italian and German troops).29

Rather than a comprehensive analysis of the Code (which would be a titanic work), I intend to restrict my observations to some points in the official ‘Report’ (Relazione)30 which the minister of justice, the Bologna lawyer Dino Grandi (1895‒1988), a former minister for foreign affairs and ambassador in London, formally presented to the king. I am not interested in highly specific technical passages but will recall some points where Grandi more openly (and strategically) quotes ancient Rome and Roman law (cf. Caprioli 2008: 200f ).

Three points of the Report should be emphasized: the importance of the terminology, the inclusion of the new codification within the fold of the Roman tradition and the value of Roman law as a general principle for the interpretation of positive law.

The terminology, while modern and perfectly matching that of legislation of 1865, regains its full historical value acquiring new meaning with the attachment to tradition:

When we say Civil Code, our thoughts go back to the notion of the Roman civis, the active member of the political community of Rome, with its well-defined position with respect to the family and civitas. This notion of civis has nothing in common with that of the citoyen of the French Revolution. The name of our code will not therefore mean that it is the code that governs the inherent rights of the citizen, as opposed to the rights of the State, much less does it mean the code of the bourgeoisie, that is, citizens of the middle classes (this concept also deriving from the French Revolution) as is sometimes called the French Code. (Relazione: 33ff, § 11)

The uncoupling of liberal values is made clear by the rejection of any connection with French revolutionary ideas: fascist revolution is another thing.

For us – continues the Minister – the Civil Code means only the code that includes the civil law, in the sense that it was originally in Rome, as defined by Gaius in his Institutions (I.1): ius proprium civitatis. It is the proper law of the Roman civitas, like the walls and the gods born with it or received in it from the people who brought it into being, a law which cannot be confused with that of any other civitas. This original concept had necessarily become discoloured later, when what was once the exclusive law of Roman citizens, members of the civitas, became the general law of all subjects of the empire of Rome, whatever the race from which they derived. (Relazione: 34, § 11)31

Grandi here retrieves a great myth of Roman law: Gaius, the second-century author, the best-known Roman jurist thanks to the discovery (by Barthold Georg Niebuhr, in 1816) (cf. Vano 2000) of a manuscript containing the text of his Commentarii Institutionum, first represents the framework which will then be repeated by Emperor Justinian in the sixth century. The political breadth of the operation is clear in the insistent appeal to the constitutional pair civis-civitas: citizenship (belonging) as the heart of the system. We could not forget the Latin wording of Mussolini, civis Romanus sum.32 The sense of the reference to tradition is already clear, but Grandi insists on the nationality of the Code:

The name ‘Civil Code’ means, then, for us, the own code of the Italian people, and first of all denotes the purely national law of the Italian people. It is the law of our race: the law that arose in Rome, when it was still the civitas, and then ruled all the subjects of the Roman Empire and, through the centuries of the Middle Ages, carefully reworked by our thriving universities, bright headlights of science, and adapted by the practical experience of our jurists, could be adapted to the needs of new times, and come down to us still alive and active, able to regulate the relations of social life in countless conditions of time and civilization. (Relazione: 34, § 11; cf. also 35, § 13)33

This point is particularly interesting: It emphasizes the connection between national tradition and race and connects ancient Roman law with its medieval and modern continuation (through the work of lawyers and universities), declaring the timelessness, the everlasting value in the practice of Roman law. The theme is repeated, and again starting from the name of the new Code: formally the same as the previous codification of 1865 (Codice civile), but different in the sense that the lawmaker claims. The name issue is central to the building of the new legal ideology; it becomes the ideal (and rhetorical) bridge between past and present:

The name given to the code then reaffirms our millennial unbroken tradition, Roman and Italian, and retrieves to its Roman origins the law of our people. The reaffirmation of our Roman law does not mean its immutability or crystallization. Roman law has proven over the centuries and through its application to many different countries such a force of adaptation that no progress in civil life was ever hindered by it. (Relazione: 24, § 12)

But here is a break: Grandi shows how tradition does not mean the stasis or immutability of Roman law. The observation could be historically founded, but in this part of the speech serves to justify the relationship of Roman law with the new regime’s ‘revolutionary’ law and the necessary adjustment of old rules to something completely different from that in which they were developed. It is clear that the problem of the relationship between past and present is here in evidence and the minister again resolves it with a rhetorical exercise. He is, to a certain extent, contradictory:

The sources of Roman law were the subject of processing for a secular time; the different generations have been able to interpret them according to their ideal needs, according to their own ideas and their own creative genius. The legal tradition was, and must be interpreted in the light of an idea. (Relazione: 34, § 12)

Even the execrable French Revolution had suited Roman law to its ideals! And, with regard to specific points of the Report in which the minister will summon Roman law as justification of a regulatory option, there are others in which he explicitly declares its uselessness. It is not a matter of opportunism with respect to the ideal declared (the perpetual importance of Roman law with a historical, genealogical connection with Italian fascist law). It is, rather, the simple revelation of the fact that that ideal reflected a political choice, very useful and strategic as a general statement, but impossible to follow when the needs of legislation (arising from economic and social links) imposed different options.

Fascinating Fascism?

The third point refers to the part of the report dedicated to Article 12 of ‘Rules on the law in general’ (Disposizioni sulla legge in generale, commonly called ‘Preleggi’), a sort of preamble to the Civil Code (but of more general validity, not limited to private law), which contains the rules on interpretation. According to this Article, in the absence of a specific provision and the inability of analogical interpretation, judges have to use the ‘general principles of the legal system of the State’. This is a typical way of integrating the provisions (necessarily limited) of a code. Even today, for example, in Austrian law (since the codification of private law of 1811), this is the way to enforce natural law in the presence of a gap in the Allgemeines Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch’s rules.

In this perspective, the Italian formula of 1942 is new: It replaces the old wording of the Code of 1865, ‘general principles of law’, which is a widespread term in Romanistic codifications (Guzmán Brito 2011: passim).34 The broadest sense includes all the rules and institutions of the State and also the national scientific tradition. Here Roman law reappears in the Report as a principle of existing law. In 1950, the Romanist Salvatore Di Marzo (1875‒1954), writing a sort of historical commentary on the new Civil Code (Di Marzo 1950: 29ff ),35 attempted to re-read the latest wording as a result of a return to genuine Roman legal thought: ‘To no Roman would it have come to mind that a case should be decided on the basis of abstract formulas and not according to the spirit of the legal system of the civitas.’ The supposed abstract formulas are – here – the general principles of the natural law tradition, taken up again by nineteenth-century codifications.

Fascinating legal fascism for a Romanist today? Not at all: The interpretation of this Article in the Relazione al Re has to be considered, in that context, a rhetorical tribute to the tradition in which the lawmaker wants to route the interpretive activity of the fascist judge,36 much more than the ultimate unveiling of the perennial actuality of Roman law. It is a rule that, as each rule (including meta-rules), has to be understood against their historical background.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Other bibliographical references can be found in Stolfi 2016: 63, n. 6. On the peculiar situation of Roman law in Italy during the fascist era, see Cascione 2009. Some relevant themes have already been briefly outlined by Casavola 1984: 4146‒8. Important for the issues here discussed is the recent work of Marotta (2013).

- In 2011, Tommaso Giaro wrote about my contribution (Cascione 2009): ‘Unter dem Titel “Romanisti e fascismo” skizziert Cosimo Cascione … eigentlich zum ersten Mal in diesem Umfang die Geschichte der italienischen Romanistik während der Musso-lini-Zeit’ (‘Under the title “Romanisti e fascismo” Cosimo Cascione outlines … actually for the first time in this extension the history of Italian Romanistic in the Mussolini era’) (Giaro 2011: 706).

- Roma s.v. Enciclopedia Italiana XXIX (Roma 1936): 589‒928; Fascismo s.v. Enciclopedia Italiana X (Roma 1932): 847‒84; Diritto s.v. Enciclopedia Italiana XII (Roma 1931): 987‒1007.

- He was one of the very few Italian university professors who in 1931 refused to swear the legally required oath of allegiance to the fascist regime. As a result, his career was curtailed until after the Second World War. Cf. Goetz 2000: 62‒75; Boatti 2001: 46‒64.

- On the political position of Bonfante, see Marotta 2015: 267‒88.

- For a short commentary on the polemic (with bibliography), see Cascione 2011.

- It is, in fact, a monograph of 677 pages signed by several prestigious experts in differ-ent fields.

- Roma s.v. Enciclopedia Italiana XXIX (Roma 1936): 589‒928; I am specifically referring to the subentry ‘L’idea di Roma – Antichità’, pp. 906‒16.

- More widely, the reference to the Roman past as a model has for centuries been a cen-tral theme of European civilization: on Rome as generator of mythology and model for cultural choices, see Giardina and Vouchez 2000.

- Sella’speech was on 14 March 1881; the fact dates back to 1871, some months after the Italian taking of Rome; cf. Marcone 2004: 220. Mommsen’s words (through oral tradi-tion) are also reported in Croce 1977: 3, where the opinion of the Italian philosopher is critical of the romantic idea of the ‘missions’ of the peoples.

- Fascismo s.v. Enciclopedia Italiana X (Roma 1932): 843. Indeed the praetores, Roman magistrates who wielded jurisdiction were escorted by lictores.

- On the assumption of the Roman salute as a social ritual in fascist Italy, see Turnaturi 2011: 120ff.

- With the Rome Treaty (22 February 1924), Italy finally obtained Fiume plus a coastal corridor connecting the town with the Italian mainland.

- The date that corresponds to the day on which Romulus, according to ancient tradi-tion, founded the city in 754 or 753 BC was fateful in the fascist view of history. In ancient times it was a pastoral new year’s day connected with spring rituals in ancient Latium, cf. Carafa 2006: 422ff. On fascist use, see Giardina and Vouchez 2000: 227ff.

- The phrase used by Mussolini is a famous quotation from Cicero (Ve r r. II 5.147, II 5.162, II 5.168; cf. Quint. Inst. 9.4.102; Gell. NA 10.3.12). Pronouncing those words in the Roman world would, in a situation of danger, be an implement of protection directed to Roman magistrates or officers, a sort of appeal to a constitutional guaran-tee of personal inviolability for the Roman citizen (in the absence of a legal process), cf. Rodríguez-Ennes 1983: 110.

- Chapter IV is entitled ‘Ritorno al futuro: la romanità fascista’.

- From a British point of view (highly critical of the Italian ‘new Roman Empire’): Gar-ratt 1938.

- For the Roman law connections, see Marotta 2013: 425ff.

- On the political aims of Augustus, see Licandro 2015.

- On the stereotype and connected themes, see Labruna 1998.

- For a brief introduction, Sarfatti 2002; more recently, from a specific historical–juridi-cal point of view, Gentile 2011, with a huge bibliography. Cf. Giardina and Vouchez 2000: 258ff.

- Following the well-known periodization proposed by De Felice 1974.

- The problem of the relationship between Nazism and Roman law is complicated, see Mantello 1987; Giardina and Vouchez 2000: 268ff; Chapoutot 2012: passim.

- Fascismo s.v. Enciclopedia Italiana X (Roma 1932): 847‒84. In particular, see the sub-entry ‘Political and Social Doctrine of Fascism’, pp. 848‒51.

- See note 3.

- The essay was published as number 3 of the series Civiltà italiana, edited by Istituto Nazionale di Cultura fascista. Cf. Cascione 2009.

- See, for example, Roma s.v. Enciclopedia Italiana XXIX (Roma 1936): 695.

- On these three capital representatives of Roman law scholarship involved with the regime, see the respective entries in the Dizionario biografico dei giuristi italiani I‒II (Bologna 2013): for de Francisci, C. Lanza in DBGI vol. I: 675‒8; for Riccobono, M. Varvaro in DBGI vol. II: 1685‒8; for Betti, S. Tondo in DBGI vol. I: 243‒5. Cf. also Mantello 2010; Marotta 2013; Bartocci 2012; Varvaro 2014; Brutti 2013: 85‒190.

- On the history of the Italian Civil code of 1942, Rondinone 2003 is now fundamental.

- ‘Relazione alla Maestà del Re Imperatore del Ministro Guardasigilli (Grandi). Presen-tata nell’udienza del 16 marzo 1942‒XX per l’approvazione del testo del Codice civile’ (1943).

- Italics in the original text.

- See note 3.

- Italics in the original text.

- On the Italian experience of 1865, see especially Guzmán Brito 2011: 507ff.

- On the position of Di Marzo towards the regime: Cascione 2009: 21ff.

- On the formative role of judicial decisions in fascist law, see Abbamonte 2011.

References

- Abbamonte, O. (2011), ‘Fra tradizione ed autorità: la formazione giurisprudenziale del diritto durante il ventennio fascista’, Quaderni fiorentini, 40 (2): 869–966.

- Albanese, G. (2016), Dittature mediterranee. Sovversioni fasciste e colpi di Stato in Italia, Spagna e Portogallo, Roma and Bari: Laterza.

- Albertario E. (1940), Il diritto romano, Milano: Giuffrè.

- Arthurs, J. (2012), Excavating Modernity: The Roman Past in Fascist Italy, Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Bartocci, U. (2012), Salvatore Riccobono, il diritto romano e il valore politico degli Studia Humanitatis, Torino: Giappichelli.

- Birocchi, I. and Loschiavo, L., eds. (2015), I giuristi e il fascino del regime (1918‒1925), Roma: RomaTrE-Press.

- Boatti, G. (2001), Preferirei di no. Le storie dei dodici professori che si opposero a Mussolini, Torino: Einaudi.

- Brutti, M. (2013), Vittorio Scialoja, Emilio Betti. Due visioni del diritto civile, Torino: Giappichelli.

- Cagnetta, M. (1990), Antichità classiche nell’Enciclopedia italiana, Roma and Bari: Laterza.

- Calamandrei, P. (2014), Il fascismo come regime della menzogna, Roma and Bari: Laterza.

- Caprioli, S. (2008), Codice civile. Struttura e vicende, Milano: Giuffrè.

- Carafa, P. (2006), ‘Introduzione’, in A. Carandini (ed.), La leggenda di Roma I. Dalla nascita dei gemelli alla fondazione della città, xiii–lxxix, Milano: Monoladozi.

- Casavola, F. P. (1984), ‘Breve appunto ragionato su profili romanistici italiani’, in V. Giuffrè (ed.), Sodalitas. Scritti in onore di A. Guarino, vol. VIII, 4133–48, Napoli: Jovene. Reprinted in (2001), Sententia legum tra antico e moderno II. Metodologia e storia della storiografia, 181‒96, Napoli: Jovene.

- Cascione, C. (2009), ‘Romanisti e fascismo’, in M. Miglietta and G. Santucci (eds), Diritto romano e regimi totalitari nel ’900 europeo. Atti del seminario internazionale (Trento 20‒21 ottobre 2006), 3–51, Trento: Università degli Studi di Trento.

- Cascione, C. (2011), ‘“Addendum”’ epistolare alla polemica Bonfante “versus” Croce (e Gentile)’, in K. Muscheler (ed.), Römische Jurisprudenz ‒ Dogmatik, Überlieferung, Rezeption. Festschrift D. Liebs zum 75. Geburtstag, 97–104, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot.

- Chabod, F. (1996), Italian Foreign Policy: The Statecraft of the Founders, 1870‒1896, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Chapoutot, J. (2012), Le Nazisme et l’antiquité, Paris: Gallimard.

- Chiari, E. (2013), ‘Review of J. Arthurs, Excavating Modernity. The Roman Past in Fascist Italy’, H-SAE, H-Net Reviews, June 2013: 1–3.

- Croce, B. (1977), Storia d’Italia dal 1871 al 1915, Roma and Bari: Laterza.

- De Felice, R. (1974), Mussolini il Duce I. Gli anni del consenso, Torino: Einaudi.

- De Martino, F. (1973), Storia della costituzione romana III, 2nd edn, Napoli: Jovene.

- Di Marzo, S. (1950), Le basi romanistiche del Codice civile, Torino: Utet.

- Evola, J. (1994 [1941]), Sintesi di dottrina della razza, Milano: Edizioni di Ar.

- Falasca Zamponi, S. (2003), Lo spettacolo del fascismo, Soveria Mannelli: Rubbettino.

- Ferraresi, F. (1988), ‘The Radical Right in Postwar Italy’, Politics & Society, 16: 71–119.

- Garratt, G. T. (1938), Mussolini’s Roman Empire, Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Gentile, S. (2011), La legalità del male. L‘offensiva mussoliniana contro gli Ebrei nella prospettiva storico-giuridica (1938‒1945), Torino: Giappichelli.

- Giardina, A. (2008), ‘The Fascist Myth of Romanity’, Estudos Avançados, 22 (62): 55–76.

- Giardina, A. and Vouchez, A. (2000), Il mito di Roma. Da Carlo Magno a Mussolini, Roma and Bari: Laterza.Giaro, T. (2011), ‘Review of Diritto romano e regimi totalitari nel ’900 Europeo. Atti del seminario internazionale’, Zeitschrift der Savigny-Stiftung fu ̈r Rechtsgeschichte. Romanistische Abteilung, 128: 706–12.

- Goetz, H. (2000), Il giuramento rifiutato. I docenti universitari e il regime fascista, Firenze: La Nuova Italia.

- Gramsci, A. (1975a), Quaderni del carcere II. Quaderni 6‒11 (1930‒1933), Torino: Einaudi.

- Gramsci, A. (1975b), Quaderni del carcere III. Quaderni 12‒19 (1932‒1935), Torino: Einaudi.

- Gregor, A. J. (2001), Giovanni Gentile: Philosopher of Fascism, New Brunswick: Transaction.

- Guzmán Brito, A. (2011), Codificación del Derecho civil e interpretación de las leyes. Las normas sobre interpretación de las leyes en los principales Códigos civiles europeo-occidentales y americanos emitidos hasta fines del siglo XIX, Madrid: Iustel.

- Hug, A. (1920), ‘Salutatio’, in A. F. Pauly and G. Wissowa (eds), Real-Encyclopädie, I A/2, col. 2060–72, Stuttgart: J. B. Metzler Verlag.

- Labruna, L. (1998), ‘Il diritto mercantile dei Romani e l’espansionismo’, in L. Labruna (ed.), ‘Tradere’ e altri studii, 79–105, Napoli: Jovene.

- Lacchè, L., ed. (2015), Il diritto del Duce. Giustizia e repressione nell’Italia fascista, Roma: Donzelli.

- Licandro, O. (2015), ‘‘Restitutio rei publicae’ tra teoria e prassi politica. Augusto e l’eredità di Cicerone’, AU PA, 58: 57–130.

- Mantello, A. (1987), ‘La giurisprudenza romana fra Nazismo e fascismo’, Quaderni di storia 13 (25): 23–71.

- Mantello, A. (2010), ‘A proposito di ‘continuità’ storiche’, in C. Russo Ruggeri (ed.), Studi in onore di A. Metro IV, 33–58, Milano: Giuffrè.

- Marcone, A. (2004), ‘Collaboratori italiani di Mommsen’, in Theodor Mommsen e l’Italia, 209–23, Roma: Atti dei Convegni Lincei.

- Marotta, V. (2013), ‘Roma, l’Impero e l’Italia nella letteratura romanistica degli anni trenta’, in G. Cazzetta (ed.), Retoriche dei giuristi e costruzione dell’identità nazionale, 425–60, Bologna: Il Mulino.

- Marotta, V. (2015), ‘“Mazziniano in politica estera e prussiano in interna”. Note brevi sulle idee politiche di Pietro Bonfante’, in I. Birocchi and L. Loschiavo (eds), I giuristi e il fascino del regime (1918‒1925), 267–88, Roma: RomaTrE-Press.

- Mommsen, T. (1887), Römisches Staatsrecht I, 3rd edn, Leipzig: S. Hirzel.

- Montagnani, C. (2012), Il fascismo ‘visibile’. Rileggendo Alberto Asquini, Napoli: Editoriale scientifica.

- Mussolini, B. (1956 [1922]), ‘Passato e avvenire’, Il Popolo d’Italia, 95 (21 April 1922): ix. Reprinted in Mussolini, B. (1956), Opera omnia XVIII, 160, Firenze: La Fenice.

- Mussolini, B. (1956 [1924]), ‘Per la cittadinanza romana’, Il Popolo d’Italia, 97 (23 April 1924): xi. Reprinted in Mussolini, B. (1956), Opera omnia XX, 234‒6, Firenze: La Fenice.Nelis, J. (2012), ‘Imperialismo e mito della romanità nella Terza Roma Mussoliniana’, Forum Romanum Belgicum, 2: 1–11.

- Nelis, J. (2013), ‘The myth of “Romanità”, “Antichistica” and the aesthetics in light of the fascist sacralization of politics, and modernism’, Mediterraneo Antico, 16 (1): 259–74.‘Relazione alla Maestà del Re Imperatore del Ministro Guardasigilli (Grandi). Presentata nell’udienza del 16 marzo 1942‒XX per l’approvazione del testo del Codice civile’ (1943), in Codice civile. Relazione del Ministro Guardasigilli preceduta dalla Relazione al Disegno di legge sul ‘valore giuridico della carta del lavoro’, Roma: Istituto Poligrafico dello Stato.

- Rodríguez-Ennes, L. (1983), ‘La ‘provocatio ad populum’ como garantia fundamental del ciudadano romano frente al poder coercitivo del magistrado en la epoca republicana’, in Studi in onore di A. Biscardi IV, 73–114, Milano: Istituto Editoriale Cisalpino-La Goliardica.

- Rondinone, N. (2003), Storia inedita della codificazione civile, Milano: Giuffrè.

- Santucci, G. (2009), ‘Diritto romano e Nazionalsocialismo: i dati fondamentali’, in M. Miglietta and G. Santucci (eds), Diritto romano e regimi totalitari nel ’900 europeo. Atti del seminario internazionale (Trento 20‒21 ottobre 2006), 53–82, Trento: Università degli Studi di Trento.

- Sarfatti, M. (2002), Le leggi antiebraiche spiegate agli italiani di oggi, Torino: Einaudi.

- Schieder, W. (2016), ‘Romanità fascista – Kaiser Augustus in der geschichtspolitischen Konstruktion Benito Mussolinis’, in E. Baltrusch and C. Wendt (eds), Der Erste Augustus und der Beginn einer neuen Epoche, Mainz: Philipp von Zabern.

- Sella, Q. (1887), Discorsi Parlamentari I, Roma: Tipografia della Camera dei Deputati.

- Skinner, S. (2015), ‘Fascist by Name?, Fascist by Nature? The 1930 Italian Penal Code in Academic Commentary 1928‒46’, in S. Skinner (ed.), Fascism and Criminal Law. History, Theory, Continuity, 59–84, Oxford and Portland, OR: Bloomsbury.

- Steiner, H. A. (1936), ‘The Fascist Conception of Law’, Columbia Law Review, 36 (8): 1267–83.

- Stolfi, E. (2016), ‘Ancora su Vittorio Scialoja (ed Emilio Betti)’, in Scritti per A. Corbino VII, Tricase: Libellula.

- Stolzi, I. (2014), ‘Fascismo e cultura giuridica’, Studi storici, 55 (1): 139–54.

- Turnaturi, G. (2011), Signore e signori d’Italia: Una storia delle buone maniere, Milano: Feltrinelli.

- Vano, C. (2000), ‘Il nostro autentico Gaio’. Strategie della Scuola storica alle origini della romanistica moderna, Napoli: Editoriale Scientifica.

- Varvaro, M. (2014), ‘Gli “studia humanitatis” e i “fata iuris Romani” tra fascio e croce uncinata’, Index, 42: 643–61.

- Vinci, S. (2014), ‘‘L’abominevole Babele del diritto’. Nazismo e fascismo fra diritto germanico e diritto romano-italico’, in A. De Martino (ed.), Saggi e ricerche sul Novecento giuridico, 59–98, Torino: Giappichelli.

Chapter 7 (127-144) from Roman Law and the Idea of Europe, edited by Kaius Tuori and Heta Björklund (Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2019), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 license.