Considering how Britain’s intellectual, political and creative circles responded to the French Revolution.

By Dr. Ruth Mather

Postdoctoral Research Associate

University of Exeter

Intellectual debate

News of the Revolution in France received a mixed response in Britain in July 1789. ‘In every province of this great kingdom the flame of liberty has burst forth,’ reported the London Chronicle, but warned that ‘before they have accomplished their end, France will be deluged with blood.’[1] Edmund Burke likewise recognised the potential of the Revolution to turn violent, but in 1790 many British people considered his Reflections on the Revolution in France to be unnecessarily alarmist. Even for moderate Britons, the Revolution could initially be seen as a belated attempt by the French to mimic the establishment of a constitutional monarchy in their own version of England’s ‘Glorious Revolution.’ The English Chronicle or Universal Evening Post, in a sensational report heavily-laden with exclamation marks declared that ‘Thus has the hand of JUSTICE been brought upon France’ and praised the men who had brought about a ‘great and glorious REVOLUTION.’[2] Others saw events in France as an inspiration. ‘Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive’, wrote William Wordsworth in his ‘Prelude’ of 1805, recalling the storming of the Bastille (Book 10, l. 696). The French example provided hope to those who wanted to extend reforms of the British government from the imperfect settlement of 1688.

Thomas Paine’s The Rights of Man began as a history of the French Revolution, but was reworked for publication in 1791 as a response to Burke’s Reflections. It not only asserted the natural birthrights of all men, but controversially advocated republicanism and a system of social welfare in the second volume, published in 1792. Although the accessible language and cheap editions of the Rights of Man made it enormously popular, Paine felt compelled to escape to France after the text was condemned as a seditious libel.

His work was defended in print by Mary Wollstonecraft, who had already published an argument against Burke’s Reflections entitled A Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790). She would go on to write A Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792), in which she advocates improved education for women in order to enable them to act as rational beings equal to men. Events in France had, therefore, provoked considerable reflection about the way society was organised along class and gender lines.

Radicalism

The controversy sparked by the French Revolution did not just inspire intellectual debate in educated circles. Influenced by Paine’s notion of universal rights, and beginning to make connections between their economic struggles and political corruption, ordinary working people began to organise into political groups for the first time, and to call for reforms that would enable them to take a more active part in deciding how the country was governed.

The London Corresponding Society was established in 1792 ‘as a means of informing the people of the violence that had been committed on their rights, and of uniting them in an endeavour to recover those rights’ in the words of its founder Thomas Hardy. Soon the society was in communication with other reform groups in northern towns including Manchester and Sheffield. The breeches-maker and LCS member Francis Place credited the Society with improving the morals and education of its humbly-born members, but the government regarded radical societies – especially those with an unlimited membership and nationwide association – as dangerous. Their fears were exacerbated by the violent turn taken by the Revolution, and once war with France broke out in 1793, the authorities sought to restrict the activities of reform societies under the guise of national security. British reformers, they argued, were far too similar to French Jacobins, the most powerful and extreme revolutionary faction. Government-sponsored journalists propagated this message in the press, while spies on the ground penetrated radical meetings and provided exaggerated reports of treasonous plots.

Conservative reactions

Not all anti-radical activity was government-led. The Association for the Preservation of Liberty and Property against Republicans and Levellers was established by the barrister John Reeves to counter the perceived threat to the British constitution. Like the LCS, the Reeves association in London communicated with the more than 200 affiliated regional offshoots, and helped to circulate conservative propaganda by the likes of Hannah More. More’s Cheap Repository Tracts were specifically designed for distribution among the poor, who, it was hoped, would absorb their messages about the benefits of good Christian morality, hard work and deference to authority in contrast to the perils of French Revolutionary ideas. Reeves himself published several tracts in defence of the existing system and was rewarded by the government for his actions, but ministers remained somewhat ambivalent about the popular conservative movement, which itself raised the spectre of mob violence it claimed to be trying to defeat.

Not all supporters of the existing constitution restricted themselves to writing pamphlets or loyal addresses to the king; some also resorted to violence to intimidate suspected radicals. While Hardy, along with fellow LCS leaders, was imprisoned awaiting trial for treason in 1794, his house was attacked by a loyalist mob, an event he blamed for his wife’s stillbirth and subsequent death. William Blake’s reference to the ‘little blasts of fear/ That the hireling blows into my ear’ in an early draft of the poem ‘London’, as recorded in his notebook, is also thought to be a reference to the intimidation he experienced as a known Revolutionary sympathiser. As Britons were encouraged to form armed associations to defend against a possible French invasion, anyone suspected of harbouring disloyalty to the British king and constitution faced the threat of physical force.

Inspiration and Division

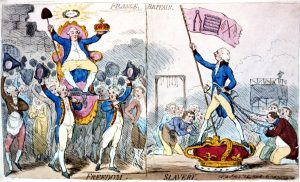

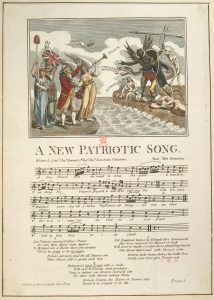

The French Revolution occurred at a time when rapid economic change was already altering the way ordinary British men and women led their lives. Both the Revolution itself and the wars which followed served to increase political awareness by stimulating intellectual debate and the artistic impulses of poets like Blake and Wordsworth or satirists like James Gillray, who found much rich material in exaggerating the extremes of opinion on either side. Yet the political polarisation of the 1790s proved deeply divisive in some communities, and the rifts were felt for years to come, re-emerging as the movement for parliamentary reform revived itself after 1815.

Footnotes

- London Chronicle (London, England), July 14, 1789–July 16, 1789; Issue 5114.

- English Chronicle or Universal Evening Post (London, England), July 18, 1789–July 21, 1789; Issue 1535.

Originally published by the British Library under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.