Many believed that celestial bodies exert a strong influence on elements and bodies in the sub-lunar world.

By Dr. Clarck Drieshen

Early Career Research Fellow

Institute of English Studies

School of Advanced Study

University of London

For many medieval men and women, the idea of a journey beyond Earth’s atmosphere would have rocked their worldview: they saw mankind as part of the ‘sub-lunar sphere’, a world where nature is temporal, changing and corruptible. The Moon and other celestial bodies, on the other hand, were thought to inhabit a region where nature is eternal, permanent and incorruptible. A journey to the Moon would have seemed all the more impossible because of the solid, impenetrable spheres through which the celestial bodies were thought to travel. If you are wondering how comets were accounted for: they were explained as atmospheric phenomena only!

Classical writings and translated Arabic sources (from the 12th century onwards) nurtured the belief that the celestial bodies exert a strong influence on the sub-lunar world — both on elements and human bodies — to such a degree that they determine the outcome of daily activities and events. This belief resulted in a variety of astrological writings that provided predictions about future events (prognostications) based on the positions of the celestial bodies. Especially popular among these writings were ‘lunaries’ or ‘moonbooks’. An example of such a lunary is the Middle English verse text The Dayes of the Mone. It presents prognostications for each of the days of the synodic month: the period between two consecutive new moons that alternately has 29 and 30 days. The text, extant in the 15th-century medical and astrological miscellanies Harley MS 2320 and Harley MS 1735, helps readers determine for each day of the lunar month whether the Moon’s position makes it into a good or a bad day for bloodletting, buying and selling, travelling, finding lost possessions, and for being born. For example, the text tells us that a child that is born today (16 July, the 23th day of a lunar month) will become ‘a good clerk’.

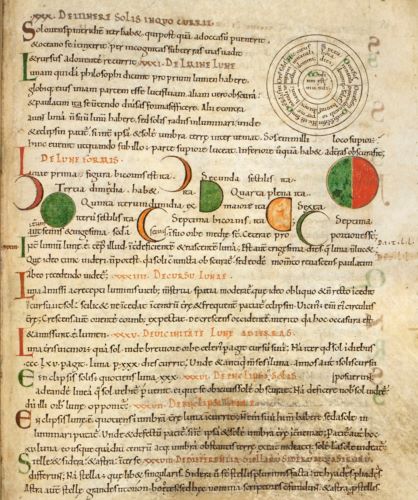

Users of lunaries had a need for diagrams and devices that could help them keep track of the lunar months. An example can be found in a mid-15th-century German manuscript (Additional MS 17987), where a lunary is preceded by a diagram that shows the phases of the Moon.

Perhaps a unique example of a ‘lunary device’ may be found in a series of four paper wheels that are sewn into parchment disks inscribed with Middle Dutch biblical citations and the year ‘1585’ (Additional MS 21549). Its function is not entirely clear, but its contents suggest that it may have been used for determining favourable days for praying for the souls of the dead.

The large wheel records the 30 days of a lunar month and cites Sirach 27:12: ‘A holy man continues in wisdom as the sun: but a fool is changed as the Moon’. The small disk in the large disk’s upper right corner allows the user to record whether a synodic month has 29 or 30 days. The wheel in the left-hand corner, numbered from 1 until 9, cites Proverbs 10:7: ‘The memory of the just is with praises’. Perhaps this wheel was used to track a period of 9 months of prayer — a so-called novena — for the souls of the dead. A separate fourth wheel, numbered from 1 until 14, states that it is holy to pray for the dead. Maybe it helped users to track the period of 14 days from the lunar month’s New Moon until its Full Moon, which may have been the preferred day for prayer.

Another unique device can be found in a 15th-century German ‘Book of Fate’ (Additional MS 25435). This book provides answers to questions related to a variety of subjects (‘hope’, ‘happiness’, ‘dreams’, ‘wealth’, etc.) provided by 28 Old Testament prophets. These prophets should be consulted on specific days of the sidereal month: a period of time that is based on the Moon’s passage through 28 segments of the zodiac (lunar mansions). In order to establish which prophet a reader should turn to for advice and on what day, the reader first needs to work his or her way to four tables with instructions from Classical and Christian authorities at the beginning of the book. For example, if your question pertains to the subject of warfare (‘crieg’), the Roman poet Cicero, in the first table, tells you that ‘what needs to be done shall be answered by Alexander [the Great]’. Alexander, in a second table, instructs you to wait until the month’s 25th day and then ask Pilate what to do. But Pilate, whose advice is found in a third table, wants you to wait until the next month’s 14th day and then consult Mercury. Mercury, finally, reveals that you should ask your question to the Old Testament prophet Zechariah on the month’s 15th day. The latter’s advice is relatively general, but allowed each reader to find a statement that was applicable to his or her situation.

What makes this manuscript remarkable is that it features a wooden panel on the inside of its upper cover with, on a moveable disk, a figure with his or her hand in a pointing position that enabled the book’s user to track the days of the sidereal month.

Today, astrology, for many, is a form of entertainment, but for many medieval men and women it was a very serious matter. Astrology gave them an insight into God’s design of the universe and intended influences of the celestial bodies on earth. The Moon was well beyond their reach, but its perceived importance was much greater than it is for most of us today. To us the Moon’s effect on earth begins and ends with its influence on the tides. For medieval men and women its tidal effect only confirmed its much wider influence on the elements and bodily humours.

Originally published by the British Library, 07.16.2017, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.