Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The Know Nothing movement was a nativist American political movement of the 1850s. It grew up as a popular reaction to fears that major cities were being overwhelmed by Irish Catholic immigrants whom they regarded as hostile to American values and controlled by the Pope in Rome. It was a short-lived movement mainly active 1854–56; it demanded reform measures but few were passed. There were few prominent leaders, and the membership, mostly middle-class and Protestant, apparently was soon absorbed by the Republican Party in the North.

The movement originated in New York in 1843 when it was called the American Republican Party. It spread to other states as the Native American Party and became a national party in 1845. In 1855 they renamed themselves the American Party. The origin of the “Know Nothing” term was in the semi-secret organization of the party. When a member was asked about its activities, he was supposed to reply “I know nothing.”

History

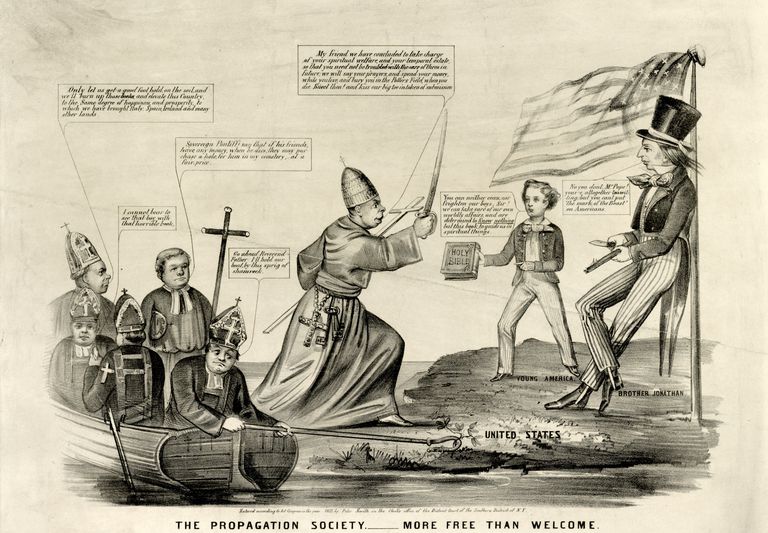

The immigration of large numbers of Irish and German Catholics to the United States in the 1830–1860 period made religious differences between Catholics and Protestants a political issue. The tensions reflected European battles between Catholics and Protestants, but were much less intense. Violence occasionally erupted over elections. Many of the anti Catholics were themselves immigrants. The biggest fear was that Catholics would undermine American democracy by creating a political network controlled by the Pope in Rome through Catholic bishops and priests. They argued that the strong allegiance of Roman Catholics to the Pope ran counter to democratic values.

Although Catholics asserted they were politically independent from their priests, Protestants alleged that Pope Pius IX had put down the failed liberal Revolutions of 1848 and was an opponent of liberty, democracy and Protestantism. These concerns encouraged conspiracy theories regarding the Pope’s purported plans to subjugate the United States through a continuing influx of obedient Catholics controlled by Irish bishops obedient to and personally selected by the Pope. In 1849, an oath-bound secret society, The Order of the Star Spangled Banner, was created by Charles Allen in New York City. It became the nucleus of some units of the American Party.

Fear of Catholic immigration led to a dissatisfaction with the dominant party, the Democrats, whose membership included many Irish American Catholics. Activists formed secret groups, coordinating their votes and throwing their weight behind candidates sympathetic to their cause. When asked about these secret organizations, members supposedly were to reply “I know nothing,” which led to their popularly being called Know Nothings.

Rise to Power

This movement won elections in major cities from Chicago to Boston in 1855, and carried the Massachusetts legislature and governorship.

In spring 1854, the Know Nothings carried Boston, Salem, and other New England cities. They swept the state of Massachusetts in the fall 1854 elections—their biggest victory. The Whig Party candidate in Philadelphia was editor Robert Conrad, soon revealed as a Know Nothing; he promised to crack down on crime, close saloons on Sundays, and to appoint only native-born Americans to office. He won by a landslide. In Washington, D.C., Know-Nothing candidate John T. Towers defeated incumbent Mayor John Walker Maury, causing opposition of such proportion that the Democrats, Whigs, and Freesoilers in the capital united as the “Anti-Know-Nothing Party.”

In New York, in a four-way race, the Know Nothing candidate ran third with 26 percent. After the fall 1854 elections, they claimed to have exerted decisive influence in Maine, Indiana, Pennsylvania, and California, but historians are unsure due to the secrecy, as all parties were in turmoil and the anti-slavery and prohibition issues overlapped with nativism in complex and confusing ways. They did elect the Mayor of San Francisco. They were still an unofficial movement with no centralized organization. The results of the 1854 elections were so favorable to the Know Nothings that they formed officially as a political party called the American Party, and attracted many members of the now nearly-defunct Whig party, as well as a significant number of Democrats and prohibitionists.

Membership in the American Party increased dramatically, from 50,000 to over one million in a matter of months in that year, it is estimated. The same member might also split tickets to vote for Democrats or Republicans, for party loyalty was in confusion. Simultaneously the new Republican party emerged as a dominant power in many northern states. Very few prominent politicians joined the party, and very few party leaders had a subsequent career in politics. The major exceptions were Schuyler Colfax in Indiana and Henry Wilson in Massachusetts, both of whom became Republicans and were elected Vice President. A historian of the party concluded:

The key to Know Nothing success in 1854 was the collapse of the second party system, brought about primarily by the demise of the Whig party. The Whig party, weakened for years by internal dissent and chronic factionalism, was nearly destroyed by the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Growing anti-party sentiment, fueled by anti-slavery as well as temperance and nativism, also contributed to the disintegration of the party system. The collapsing second party system gave the Know Nothings a much larger pool of potential converts than was available to previous nativist organizations, allowing the Order to succeed where older nativist groups had failed.

Tyler G. Anbinder, Nativism and Slavery, p. 95

In 1854, alleged members of the American Party stole and destroyed the block of granite contributed by Pope Pius IX, intended for the cornerstone of the Washington Monument. They also took over the monument’s building society and controlled it for four years. What little progress occurred in their tenure had to be undone and remade.

In spring 1855, Levi Boone was elected Mayor of Chicago for the Know Nothings. He barred all immigrants from city jobs. Statewide, however, Republican Abraham Lincoln blocked the party from any successes. Ohio was the only state where the party gained strength in 1855. Their Ohio success seems to have come from winning over immigrants, especially German Lutherans and Scottish Presbyterians who feared Catholicism. In Alabama, the Know Nothings were a mix of former Whigs, malcontented Democrats, and other political outsiders who favored state aid to build more railroads. In the tempestuous 1855 campaign, the Democrats convinced state voters that Alabama Know Nothings could not protect slavery from Northern abolitionists.

Decline

The party declined rapidly in the North in 1855–56. In the Election of 1856, it was bitterly divided over slavery; one faction supported Millard Fillmore who won 23 percent of the popular vote and Maryland’s eight electoral votes. He did not win enough votes in Pennsylvania to block Democrat James Buchanan from the White House. Most of the anti-slavery members of the American Party joined the Republican Party after the controversial Dred Scott ruling occurred. The pro-slavery wing of the American Party remained strong on the local and state levels in a few southern states, but by the Election of 1860, they were no longer a serious national political movement.

Some historians argue that in the South the Know Nothings were fundamentally different from their northern counterparts, and were motivated less by nativism or anti-Catholicism than by conservative Unionism; southern Know Nothings were mostly old Whig Partys who were worried about both the pro-slavery extremism of the Democrats and the emergence of the anti-slavery Republican party in the North. In Louisiana and Maryland, the Know-Nothings enlisted Catholics. Historian Michael F. Holt, however, argues, “Know Nothingism originally grew in the South for the same reasons it spread in the North—nativism, anti-Catholicism, and animosity toward unresponsive politicos—not because of conservative Unionism.” He quotes ex-Governor William B. Campbell of Tennessee, who wrote in January 1855, “I have been astonished at the widespread feeling in favor of their principles—to wit, Native Americanism and anti-Catholicism—it takes everywhere.”

Platform

The platform of the American Party called for, among other things:

- Severe limits on immigration, especially from Catholic countries.

- Restricting political office to native-born Americans

- Mandating a wait of 21 years before an immigrant could gain citizenship.

- Restricting public school teachers to Protestants.

- Mandating daily Bible readings in public schools (from the Protestant version of the Bible).

- Restricting the sale of liquor.

References

- Anbinder; Tyler. Nativism and Slavery: The Northern Know Nothings and the politics of the 1850s. New York: Oxford University Press 1992.

- Gienapp, William E. The Origins of the Republican Party, 1852–1856. New York: Oxford University Press 1978.

- Griffin, Clifford Stephen. Their brothers’ keepers: moral stewardship in the United States, 1800-1865. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press 1983.

- Holt, Michael F. The rise and fall of the American Whig Party: Jacksonian politics and the onset of the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Holt, Michael F. Political Parties and American Political Development: From the Age of Jackson to the Age of Lincoln. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1992.

Originally published by New World Encyclopedia, 04.03.2008, under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.