The spatial sign in the middle ages is the product of the mythology of static, determinate structure.

By Dr. Jesse M. Gellrich

Professor of English

Louisiana State University

The Divine Page, in its literal sense, contains many things which seem both to be opposed to each other and, sometimes, to impart something which smacks of the absurd or the impossible. But the spiritual meaning admits no opposition; in it, many things can be different from one another, but none can be opposed.

Hugh of St. Victor, Didascalicon

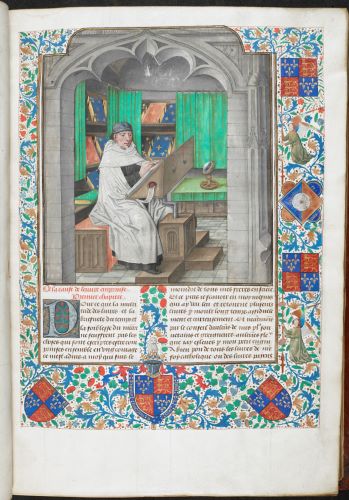

If mythology in the middle ages is understood according to the argument set forth so far, as a specific structure of thought rather than simply an inherited collection of legends and characters, then the origin and growth of medieval spatial forms appear in a new light: the supposed displacement of pagan by Christian ideology was not as clear-cut as those forms might suggest, and thus the hold on the past was quite a bit tighter than medieval opinion would have it. Although the old pagan deities were renamed or reformulated for new purposes, they still figured prominently in patterns of thought that were fixed and centered, and those structures were not so easily called into question. Furthermore, they were an integral part of many traditions in the middle ages-from the classification of trees, animals, and stars in the study of nature to the Gothic style in architecture, manuscript painting, and philosophical argumentation. The “mythology” of these forms consists in their encyclopedic and totalizing structure, which has roots not in the intellectual processes that developed to explain them-such as the summae of Scholasticism -but in the presence of meaning in spatial form. This conception of mythology is customarily illustrated in the ancient world out of which Christianity emerged and the archaic societies it encountered during its movement through medieval Europe and Britain, but it is no less operative in the so-called Book of cultural forms in the middle ages. To the extent that this Text is composed of the replication of familiar schemata, such as the firm outlines dominating Romanesque and Gothic painting or the sacralization of stone and volume in church architecture, the semiology of spatial patterns is characterized by the repetition and emphasis of earlier forms, rather than by deviation from them, until the elaboration of past models gives place-by the end of the fourteenth century-to an interest in sheer ornamentation and cleverness for their own sakes (as may be noticed, for instance, in the work of Bosch).

The development of spatial forms of the sign in medieval tradition invites a certain comparison and contrast with the linguistic sign, in both its spoken and its written manifestations. If the semiology of space is characterized by elaboration and repetition over the centuries, we are led to inquire about the fate of the linguistic sign as it was treated in several medieval disciplines of learning by writers ranging from Augustine, Donatus, and Priscian in the fourth and fifth centuries to Aquinas and the speculative grammarians, or modistae, after the twelfth. Treatments of this subject, whether they are products of grammatica in the trivium or the hermeneutics of Scripture in the quadrivium, are controlled in some ways by the same repetition of auctoritates that determines the growth of spatial forms. However, the comparison is far from simple, not only because we cannot draw an easy equivalence between spatial and written or spoken signs, but also because medieval reflections on the linguistic sign undergo many complicated and rich variations.1

Whereas spatial forms are organized by an effort to contain and make present their objects of signification, some approaches to the linguistic sign appear to lead in a different direction when language is explained as a conventional, rather than a natural, representation of meaning and when the word is studied for its various “ways of signifying.” The spatial sign in the middle ages is the product of the mythology of static, determinate structure, of the totalizing containment that subsumed cultural forms into a Book. Its influence, as suggested heretofore, spread well beyond visual materials, governing even the conception of writing in Scripture and the Book of nature. But it is now relevant to look in finer detail at the structure of medieval mythologizing in relation to the signs of writing and speaking. Does the linguistic sign follow a path similar to its spatial counterpart and contribute to the same mythology? A response to this question may be undertaken by considering whether the study of signs, grammar, and language became at certain points in the middle ages the ground for new departures and changes in the modes of signification.

We do not look far in medieval writings about verbal signs without noting the frequent reference to them as natural entities-the word as “seed,” the pen as “tongue.”2 Such descriptions appear mostly commonly in comments on the hermeneutics of Scripture, and if they constitute a prevailing conception about the language of God, they exist in contrast to the understanding that linguistic meaning, whether natural or not, is never free from problems of inconsistency and misunderstanding. No one asserted this dilemma about the meaning of words more sharply than Martianus Capella. In the Marriage of Mercury and Philology, Martianus provides the personified figure of grammar with a knife, a stick, and a box of medicines. Each has its function, which was not forgotten in the subsequent history of grammatical studies, as is obvious in John of Salisbury’S recollection, in the Metalogicon, of Martianus’s image: grammar employs the knife, says John, to cut away linguistic errors and to purify the speech of the young; she uses the rod to suppress those who “babble in barbarisms and solecisms”; but then “with the ointment of … propriety and utility,” she eases the pain of her patients.3

In her function as “nurse” of language, grammar serves Martianus, John, and other medieval commentators on the trivium as a system for controlling meaning and establishing the study of linguistics as fundamentally subservient to semantics. “If, therefore, grammar is so useful,” John continues, “and the key to everything written, as well as the mother and arbiter of speech, who will [try to] exclude it from the threshold of philosophy?4 The rhetorical question insists on the basic medieval belief that grammatica is the first of the seven liberal arts and absolutely indispensable for ascending the hierarchy of learning through the quadrivium, especially to the higher reaches of ethics and theology. While John’s battle in the Metalogicon is directed immediately against detractors of the trivium, which had come under increasing attack in his time at Paris and Chartres, his enemy is not local: John writes against a general ignorance of systematic grammar. In fact, the nom de plume of his fictional adversary-one “Cornificius”-is apparently taken from Donatus’s fifth-century Vita Vergilii, in which Cornificius is the name given to Virgil’s detractor. John clearly faced the same problem as Donatus and other early medieval grammarians: linguistic signification is, to a certain extent, uncontrollable, an errant child who must be curtailed by the parental rod, or a sick body in need of grammar’s medicine.

When medieval writers considered the question of signification, if they did not think of Martianus’s rod, they surely had access to another story about language that was quite a bit more influential because of its scriptural authority, the account in Genesis 11 of the dissemination of languages after the destruction of Babel. Relating how God decides to “confound” (confundamus; Gen. 11.7) the original “one tongue” (unum labium; Gen. 11.5) leaving a state of linguistic chaos throughout the earth (“confusus est labium universae terrae”; Gen. 11.9), the story suggested to medieval readers the devastating loss, like the fall of man, from the presence of God’s words and thoughts-the time when meaning had no mediation and intention was undifferentiated.’ “Why,” asks John of Salisbury of the detractors of grammar, “do you not at least know Hebrew, which, as we are told, mother nature gave to our first parents and preserved for mankind until human unity [unitatem]5 was rent by impiety, and the pride which presumed to mount to heaven by physical strength and the construction of a tower, rather than by virtue, was leveled in a babbling chaos of tongues [confusione linguarum]?” The original language, he continues, “is more natural than the others, having been, so to speak, taught by nature herself [natura docente loquuntur].”6 But in the postlapsarian world, the state of speaking and writing after Babel, only a nostalgia for an originary oneness of natural meaning survives, as readers and speakers, like the Hebrews themselves, wander in the exile of many disparate tongues. Among the medieval seven liberal arts, grammatica was the first bulwark against further confusion and dissemination, and the continuing appeal to the works of Priscian and Donatus, though devoted to classical Latin, provided the means for shoring up meaning against the ruin of misreading.

The unrivaled popularity of the Ars grammatica and the Institutiones grammaticae as teaching tools of grammar throughout the early middle ages (Priscian’s treatise survives in over one thousand manuscripts) constitutes a paradox of linguistic history, since medieval Latin could not be pressed without strain against the matrix of classical Latin.7 It is no surprise at all to encounter objections, such as the remark of Smaragdus of St. Michel (ninth century): “I disagree with Donatus because I hold the authority of the Scriptures to be greater.”8 The question of which has priority, classical or vulgar Latin, was a medieval commonplace, but it explains the undeveloped theory of grammatica less than it indicates the firm hold of the Babel story on the medieval consciousness. If an ideal state of language is assumed-as Hebrew was imagined to represent the thoughts and speech closest to God-it was inevitable that subsequent tongues would appear as rivals for priority. Now the mother tongue, Latin, has taken the place of Hebrew as the Ursprache, leaving the language of the Vulgate Bible in conflict with the language of Virgil and the Roman poets.

The inclination to protect signification from dissemination that is apparent in this appeal to the correct speech of God is validated by more subtle forms in medieval linguistic history, such as in the accessus ad auctores. Specifying the place of Priscian in the curriculum of studies, a thirteenth-century accessus shows the privilege granted to the spoken word before any correct appreciation of the written is possible: “praua pronunciatio quam praua copulatio.” Bad copulatio-conjugation of noun and verb-follows from bad pronunciation, and the unavoidable mistake will be the inability to tell “domine” from “dominum.”9 Grammar’s knife and rodPriscian’s firm advice on the correct syntactic functions of the eight pars orationes, or parts of speech-are definitely in hand in this late medieval example. A simple warning about pronunciation is controlled by a larger mythology in which the spoken is privileged as a model of the written and an ideal state of language is identified with the stabilization of signification that is always under threat of erosion by the lesser, diminished fo rms of speaking and writing.

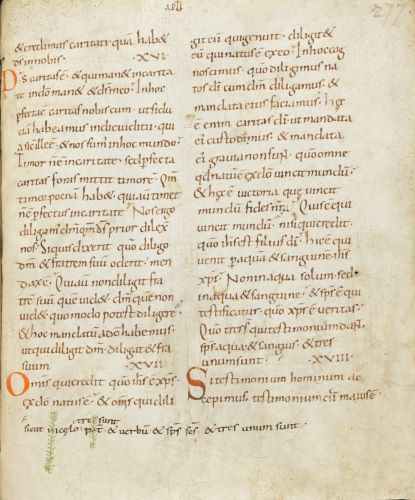

The attempt to stabilize dialectical habits and solidify the flux of individual instances of language-which was surely the effect of perpetuating Donatus and Priscian in the curriculum-may be noticed as well in more rarefied and sophisticated studies, such as the reflections on the nature of the written word in Scripture. For example, in a telling page of the Didascalicon, Hugh of St. Victor reveals brilliantly a way out of the wandering confusio of the fallen state of signs by ascending back up the hierarchy to the primal word spoken by God:

The substantial word is a sign of man’s perceptions; the thing is a resemblance of the divine Idea. What, therefore, the sound of the mouth, which all in the same moment begins to subsist and fades away, is to the idea in the mind, that the whole extent of time is to eternity. The idea in the mind is the internal word, which is shown forth by the sound of the voice, that is, by the external word. And the divine Wisdom, which the Father has uttered out of his heart, invisible in Itself, is recognized through creatures and in them. From this is most surely to be gathered how profound is the understanding to be sought in the Sacred Writings, in which we come through the word to a concept, through a concept to a thing, through the thing to its idea, and through its idea arrive at Truth.10

Hugh’s reflections on the language of the Bible derive from his earlier concerns in the Didascalicon with the place of grammatica in the trivium and quadrivium, and he is entirely conventional in his advice. He even offers us an instance of the vertical probing back to the original source for meaning in his etymological gloss on the names “quadrivium” and “trivium.” They are so called, he says, “because by them, as by certain ways (viae), a quick mind enters into the secret places of wisdom.”11 While his immediate aim is with teaching his pupils how to read the Bible correctly, his linguistics is thoroughly informed by medieval commonplaces about language, such as those that inform Donatus and Priscian. Like them, Hugh offers an apologetics against linguistic confusio ; language is a transparency through which meaning may be reached by ascending the hierarchy to the origin of truth; signification is identified with a parent word or an original language before the taint of differentiation and mediation; linguistic change is conceived of as a moral vice (the sin of pride in the Babel story) and a disease in the primal tongue of speaking and writing. While theoretical stability was the obvious effect of perpetuating such a “logocentric” hierarchy for medieval writers on language, the facts of linguistic usage would inevitably present an ongoing challenge to grammatica; but oddly enough, it was not the data of experience that brought about the next development in medieval linguistic history. It was initiated instead by the reintroduction of speculative logic and metaphysics -primarily from Aristotle-in the disciplines of study during the twelfth century.12

Because of the impact of logic and dialectic on grammar after 1100, it may appear somewhat anachronistic that John of Salisbury, like the early medieval commentators, appeals to an original, natural language as a model by which subsequent languages and dialects might be described. Following the work of Peter Abelard, Anselm of Laon, and William of Conches, Peter Helias-who was John’S teacher-did more than any previous commentator to establish grammar as an autonomous discipline, a “language” in itself that sought to encompass all aspects of linguistic study.13 The “metalanguage” of grammatica that Peter Helias taught was the product of much innovative thinking about Donatus and Priscian, and John’s Metalogicon shows the results. But John’s book is not, finally, anachronistic, since the twelfth-century grammarians, such as Peter Helias, approach the problem of linguistic signification by reference to a model that has much in common with some of the early medieval reflections on language. Accordingly, it may not be quite accurate to divide linguistic history in the middle ages into the customary “periods” -the early teachings of grammatical commentators before 1200 and the extensive speculations that followed that date.14 For writers like John of Salisbury show that in language theory, as in so many other medieval traditions, the continuity of auctores and auctoritates appears to prevail over radical change.

For example, with regard to the subject of the origin of words and letters, John echoes several previous disputes about whether they are natural or human.15 Priscian had argued that they are contrived by man and yet remain tied to material things: men “pronounced letters by means of a vocabulary of elements according to a similitude with elements of the world” (“literas autem etiam elementorum vocabulo nuncupaverunt ad similitudinem mundi elementorum”).16 For John of Salisbury, “the very application of names, and the use of various expressions, although much depends on the will of man, is in a way subject to nature, which it probably imitates.” Consequently John insists that, although the grammatical study of language is “an invention of man,” still it too “imitates nature, from which it derives its origin” (“naturam tamen imitatur, et pro parte ab ipsa originem ducit”).17 Because of the emphasis on the roots of names or words in their sources, letters were commonly thought to carry with them something of their origins. Isidore recognizes this representational aspect of letters when he says that they are “the indices of things, the signs of words”; but nonetheless, he also goes on to observe that in letters “there is such power that they speak to us without voice the discourse of the absent” (“dicta absentium sine voce loquantur”).18 John knew this passage from the Etymologiarum and inserted it almost verbatim into his Metalogicon (1.13).19

Yet in the conception of the word as an imitation of its source, John is also indebted to his language teacher. Peter Helias, in his effort to free linguistic study from questions that were not precisely grammatical, appropriates an early medieval opinion (from Priscian) when he comments that verbs were invented to signify substances proprie-“principally” or “properly.”20 But his excursus shows the subtle influx of dialectic; for he goes on to explain that they were created to designate the “action” and “passion” of a substance and later became extended to cover “qualities” and other “accidents.” This principle allows a certain latitude in solving such problems as Priscian’s verbum substantium, namely, that est as a verb designates an action or passion, and yet as a substantive it signifies things as existing. Peter argues his way out of this dilemma by claiming that, first of all, a substance unites all other things to itself (“substantia itaque unitiva est accidentium”); as derivative elements return to their source, so the verbal substantive is unitary and copulative (“omnia namque accidentia in se recipit et sibi copulat et unit”).21 Thus, though esse signifies a substance, it does so in the manner of an action (“quia licet substantiam significat, modo tamen action is earn significat, ut determinatum est”).22 In Peter’s solution, a certain flexibility informs the question of signification: nouns signify by naming “properly” the substances on which-as John says- they are “stamped”;23 but verbs signify differently, as is apparent in the example of verbal nouns; they also signify their sources, yet do so in modo actionis.

However, the difference granted in this important grammatical principle of the twelfth century is not as various as it may seem, since the larger issue of derivative signification-consignificatio-it introduces was itself rooted in a controlling parent structure.24 For instance, many medieval grammarians worried the question of how the word “whiteness” signifies when it is a noun (albedo), or a verb (“is white,” albet), or an adjective (“white,” album).25 But while this example illustrates that they were touching on different “ways of signifying” in connotative functions, it would be wrong to imagine that they were unearthing a principle of linguistic indeterminancy. Terms differ manifestly in their simultaneous secondary meanings-their consignification; but they never lose possession of the primary stem from which they derive. John of Salisbury addresses this knotty problem by recalling what Bernard of Chartres used to say about it: “‘Whiteness’ represents an undefiled virgin; ‘is white’ the virgin entering the bedchamber, or lying on a couch; and ‘white’ the girl after she has lost her virginity.”26 If signification is gradually tainted as a word enters syntax, John goes on to explain, the linguistic state of privilege, the chastity and virginity of pure meaning (albedo), is a quality without “any participation of a subject [sine omni participatione subjecti],,; but the consignification of syntax will inevitably violate that quality through “participation by a person” until the “whiteness” of unqualified meaning is “infused” and “mixed”- “in a way still more impure [corruptam].”27

The virginity of signification remains open to the mixing of senses, but by identifying consignificatio with deflowering, perhaps even with sin, John and Bernard illustrate yet another strand of the many lines leading back to the natural, pristine state of meaning before Babel: signification sine participatione subjecti is nothing less than the unmediated language of God. While the impurity of syntax is unavoidable, the perpetuation of virginal meaning (like ecclesiastical chastity) is the preferred condition, and it was consistently sought, as we will see shortly, in the discipline of ecclesiastical writing-biblical hermeneutics and exegesis. But first it will be necessary to consider a bit further whether grammatica remained rooted in the mimesis of nature after the twelfth century.

The work of Peter Helias and other twelfth-century grammarians was to have a profound impact not only immediately on treatises for teaching grammar, such as the Doctrinale of Alexander of Villedieu (one of the most popular texts at the end of the century), but also more remotely on the many writers who turned their attention to grammar in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries; for example, Robert Grosseteste, Peter of Spain, Roger Bacon, and the modistae-Martin of Dacia, John of Dacia, Siger of Courtrai, Michel de Marabais, and Thomas of Erfurt. The contribution of twelfth-century grammatica was elaborated and refined in theory and terminology by each of these writers, and, as with Peter Helias, their fundamental intention was to establish grammar as a self-consistent system through the study of language per se. But it is hardly surprising, in view of the impetus to study grammar by virtue of advances in dialectic and logic, that grammarians saw their subject through the lens of philosophical categories. On the one hand, the assistance of philosophy emphasized even more an interest in how language signified, rather than in what it signified, and this direction produced many texts in “speculative grammar,” de modis significandi. But on the other hand, in spite of an approach to the elements and functions of language as the products of convention, individual languages were not for the most part the concern of linguists in the thirteenth century or of the later modistae.28 Roger Bacon, for instance, sums up much of the theoretical speculation of his age when he maintains that there really is only one grammar, which is subordinate to the nature of the physical world and the structure of human understanding: “grammar is one and the same according to the substance in all languages.” And therefore he is led to insist that it is “not the grammarian, but the philosopher, diligently considering the proper natures of things, who sets down grammatical principles.”29 In this remark is buried the assumption of the thirteenth century that the primary object of grammatica is the self-sufficiency of Latin as a metalanguage for organizing the discipline itself, rather than for describing specific linguistic instances.30 Vox unde vox, the concrete occurrences of speech that illustrate conceptions about the general category of voice, was in effect a mirror image of the order of understanding, or modus intelligendi.

In the next century, Thomas of Erfurt, who wrote one of the most complete texts in grammatica speculativa, carries out Bacon’s rule when he argues, with regard to sentence construction: “grammar is organic” (grammatic a … sit organicum”); and consequently each element of the discipline must be “ordered towards some … necessary end or purpose.”31 Like the sentence, so also the discipline of studying it-Thomas’s remark is hardly casual. The structure of thought pars pro toto, as it is illustrated in the many spatial forms of the sign already considered, determines as well the organization of grammatica among the modistae. We see it most clearly as they appropriate the terminology of Scholastic logic for the description of linguistic phenomena. The contrast of matter and form, which had been used by previous grammarians, is emphasized again by the modistae, but with new philosophical rigor-for instance, in distinguishing the material appearance of a word, or dictio, from a formal class of words, or pars orationis. Owing to a difference in form, therefore, the dictio denotes a meaning while the pars orationis has the potential of connoting derivative sense. The Scholastic interest in act and potency plays a large role in such distinctions, determining the classification of all modi significandi as “acts” and modi intelligendi and consignificandi as the “potencies” of those acts.32

Defining the parts of speech according to the modes of signifying, the modistae move beyond their predecessors by locating the domain of linguistics between “being” (essens or ens) and “understanding” (intelligens), and this situation allows it to mirror both orders simultaneously. Siger of Courtrai, for example, says that the noun “is the mode of signifying substance, permanence, rest, or being” (“modus significandi substantiae, permanentis, habitus seu entis”); but the verb is a “mode of signifying becoming or being” (“modum significandi fieri seu esse”).33 Temporality and action are the crucial distinctions in the mode of the verb for Siger, controlling his use of ens for the noun that may perform a certain ac-tion or esse. It is clear that philosophical interests push Siger a bit further than linguistic description per se when he concludes that verbs must follow their nouns since the state of esse (action) obviously fol-lows the state of ens (rest).34

In Thomas of Erfurt’s Grammatica speculativa, the modis tic determination to describe grammar in itself is again unmistakable; but the study of language as a phenomenon of convention, which had otherwise opposed medieval notions of the natural presence of meaning, reveals that language theory through the fourteenth century did not finally displace an archaic natural matrix.35 Thomas begins his treatise with as sharp an attention to the modus, rather than the object, of signifying as we are likely to find in fourteenth-century grammar; he says that modes of signifying are twofold, taking their form from the active and passive modes of understanding and moods of the verb. But the priority of the source or the object determines his description: “every active mode of signifying comes from some property of the thing” (“omnis modus significandi activus est ab aliqua rei proprietate”).36 The convention of linguistic description, in this instance, remains subordinate to what is natural to the “thing,” its proprietas. This point might not be assumed in, for example, grammatical gender, since it seems mechanically, perhaps arbitrarily, assigned by convention. Not so for Thomas, who finds in it the operation of a law of sexual differentiation: “masculine gender is the mode of signifying the thing by means of the property of acting (… vir). Feminine gender is the mode of signifying the thing by means of the property of being acted upon ( … mulier).”37 As a linguistic category has here changed places with, and even determined, a logical one (the modus intelligendi activi and passivi), grammar is imitating nature, which is in turn imitating it.

Proprietas as a determinate of meaning takes on more complex proportions in the case of the demonstrative pronoun, because it “signifies the thing by means of the property of presence” (“proprietate praesentiae”).38 The indications of presence are six for Thomas, one each for the five senses, plus one for the intellectual sense. In the example, ille currit, demonstration is synonymous with presence: the dictio makes its meaning immediate to the physical sense and is present in it. However, some demonstratives, says Thomas, are not so simple. For instance, if someone points to a bunch of grass held in the hand and observes, “This grass is growing in my garden,” it is obvious that one thing “is demonstrated” (demonstratur) and something else “is signified” (significatur). In this case the grass in the hand is present to the physical sense, and the grass in the garden is conveyed to the intellectual sense; there must be different “modes of demonstrating,” he continues, because of the “different modes of certainty and presence” (“diversos modos certitudinis, et praesentiae”).39 In order to take care of the separation in these examples between demonstrative elements and signification, Thomas separates the perceptual categories. But nowhere does his example, despite its suggestiveness, invite him to deviate from his first principle-the conception of spoken or written utterance as a property of the presence of meaning. Rather, he concludes, we simply move from what is “really established or present, which is demonstrated by the pronoun ego” to what may be “less certain and present … which is demonstrated by the pronoun tu, and so on” (“contingit enim rem esse praesentem et certam, et maxime certam vel praesentem, et sic demonstratur per hoc pronomen ego, vel non maxime esse certam et praesentem, et sic demonstratur per hoc pronomen tu, et alia similia”).40

In this conception of relative degrees of presence that correspond to a graduating order of pronouns, we notice yet again the influential force of a precedent model, for example, Hugh of St. Victor’s linguistic hierarchy that descends from the absolute Verbum to the lower manifestations of the written and spoken, internal and external word. The matter of which has priority speech or writing, demonstrative utterance or signified meaning, the grass in the hand or the grass in the garden-does not really call into question Hugh’s or Thomas’s basic idea of the identity of discourse with presence. But this factor also means that, for Thomas and the other modistae, the modus essendi is just as much defined by as it defines its modus significandi. In fourteenth-century grammatica, many elaborate examples suggest that the modistic effort to describe linguistic phenomena in themselves remained rooted in ideas about the structure of reality and the mind. It is a discipline well aware of the separation of language from meaning, yet tied deeply to early medieval linguistic models, such as those of Donatus and Priscian, whose grammatical systems are still intact as late as Thomas of Erfurt.41 Like the early commentators, the modistae created a metalanguage that mirrors its own self-sufficiency much more than it analyzes the dictiones of usage.42 While this development protects signification from indeterminacy, it also forestalls the advance of distinctly new directions in thinking about the origin of language and the modes of signifying meaning.

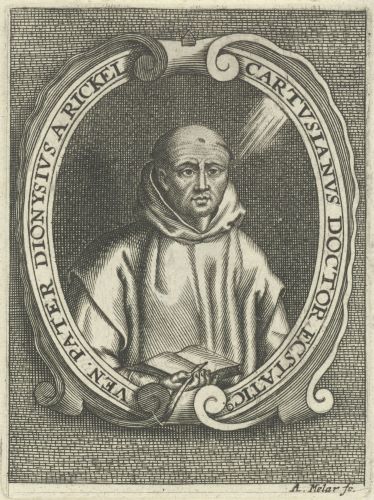

If grammatica does not isolate the study of language from the structures of past models or other disciplines of the trivium-as the various moments in the history of the discipline considered thus far suggest-we may expect that the treatment of linguistic signs in other fields of learning illustrates a similar tendency. Such is the case, it seems, in the hermeneutic theory and practice of reading Scripture, and the reasons for it are not at all remote. Hugh of St. Victor and other grammarians have already pointed to them: signs are defined in this field of knowledge not for their own sake, but primarily and explicitly for the value of reading the Bible correctly. In view of the extensive development of medieval hermeneutics-its growth into an institution of reading after the fathers of the church and flourishing at least until the time of Denis the Carthusian -the theological force of its approach to language not only discloses how scriptural signs were defined and understood, but also indicates why the effort to study language per se in other disciplines (for example, grammatica) remained conditioned by the past. This situation, like the perpetuation of classical Latin as a model in grammatica, seems paradoxical, since hermeneutics in the middle ages takes its origin from vivid instances of differentiation, such as the theoretical effort to separate transcendent reference from linguistic expression, which was illustrated historically for medieval readers not only by the story of Babel, but also by the Hebrew repudiation of pagan images and habits of thought heard frequently in the prophetic books of the Old Testament.

Determined to establish a transcendent and abstract sense of divinity, a frame of reference beyond adequate representation in concrete and particular things, the Hebrew protest shows little patience with the signifying systems of the Egyptians and Sumerians, which have been characterized in the following way:

The primitive uses symbols as much as we do; but he can no more conceive them as signifying, yet separate from, the gods or powers than he can consider a relationship established in his mind-such as resemblance-as connecting, and yet separate from, the objects compared. Hence there is coalescence of the symbol and what it signifies, as there is coalescence of two objects compared so that one may stand for the other. In a similar manner we can explain the curious figure of thought pars pro toto, “a part can stand for the whole”; a name, a lock of hair, or a shadow can stand for the man because at any moment the lock of hair or shadow may be felt by the primitive to be pregnant with the full significance of the man.43

While this form of signifying remains grounded in material substances, it would be incomplete to assume that it is incapable of becoming a basis for engaging abstract problems; and yet the Hebrew opposition demanded a capacity for reference to a transcendent order that would not be limited in any way by materiality. Medieval hermeneutic theories of the sign are conceived in that imperative, but the signans (or signifying means) was often described as carrying with it or within it a part of its signatum (or signified reference). Since this structure of the sign-pars pro toto-has been commonly defined in the history of semiology as an instance of “symbolic” form, it will be useful to begin hermeneutic considerations of the sign with reference to the movement toward and away from symbolic structure.44 Thus defined, symbolic signifying has direct bearing on the nature of abstraction in hermeneutics and relates more broadly to the problem of the stability of signification in the middle ages.

The question of the extent to which abstraction figures in commentaries on hermeneutics may begin with reference to Aquinas, since he explicitly takes up the problem of symbolic signification in a discussion of the place of metaphor in biblical texts. Engaging the issue “Whether Holy Scripture Should Use Metaphors and Symbols” (De sacra doctrina, article 9), Aquinas answers the objection, “It seems that Holy Scripture should not use metaphors,” by acknowledging first the usual oppositions: similitudes are befitting only to poetic art, “the lowest of all sciences”; comparisons obscure truth; representations of the divine ought to be made from “nobler” likenesses but are frequently drawn from “lower” ones.45 Relying on conventional ideas about Scripture, Aquinas affirms, “it is natural to man to seek intellectual truths through sensible things, because all our knowledge originates from sense. Thus in Holy Scripture spiritual truths are appropriately taught under the likeness of metaphors taken from bodily things. This is what Dionysius says: ‘Divine rays cannot enlighten us unless they are covered by many sacred veils.'” Such representations only give “delight” in poetry, Aquinas continues, but in Scripture they are “both necessary and useful,” since sensible imagery provokes sensitive minds not “to remain within the likenesses, but elevates them to the knowledge of intelligible truths.” If Scripture employs likenesses of the divine to “less noble bodies,” the intention is not to confuse but to lead the mind away from error, “for such expressions in their proper sense are not said of divine things.” Furthermore such knowledge is more befitting the understanding of God proper to creatures: “for what he is not is clearer to us that what he is.”46 With that remark we are as far from equating an image with a transcendent referent as we are, for instance, in Ferdinand de Saussure’s separation of the sign from the nomination of a thing.47 But we have not left the realm of symbolic form.

In one of Aquinas’s sources for article g, Dionysius the Areopagites On the Celestial Hierarchy, the argument against mistaking the similitudes in Scripture for the true nature of God respects a sacred balance that is based upon the difference between the signified and what signifies it. Beginning with the assumption that divine nature is unknowable in its essence, Dionysius affirms that between the two ways Scripture describes holy mystery-through positive similitudes and negative or “unlike” comparisons-the via negativa “accords more closely with that which is ineffable.”48 According to Dionysius, the danger in positive comparisons is that “we might even think that the supercelestial regions are filled with herds of lions and horses, and re-echo with roaring songs of praise, and contain flocks of birds and other creatures.” “We might fall into the error of supposing that the Celestial Intelligences are some kind of golden beings, or shining men flashing like lightning, fair to behold, or clad in glittering apparel.”49 To avoid such errors, Scripture employs “unlike images” or negative comparisons that do not allow the facile identification of image and referent, appearance and reality. Since divine nature “transcends all essence and life,” words and wisdom are “incomparably below it.” When it is named “Invisible, Infinite and Unbounded” we are told “not what It is, but what It is not,” and this “is more in accord with Its nature.” Accordingly “inharmonious dissimiltidues” or negative images do not risk the identification of sign with signified because an “unseemly image” cannot be mistaken for that which surpasses all comparison.50 In other words, the unlikeliness of the image provokes the search for spiritual truth. Since the similitude is equivalent to the whole of which it is only a part, the structure of the sign for Dionysius remains symbolic.

However, in Aquinas’s other important source for article 9, Augustine’s De doctrina Christiana, book 2, the differentiation of the sign is not so easily compromised. Augustine begins book 2 by departing from his earlier discussion of “things” (res) in order to take up the “sign” (signum), but the materiality of the res has left its mark on the idea of the signum. “Just as I began,” he argues:

when I was writing about things, by warning that no one should consider them except as they are, without reference to what they signify beyond themselves, now when I am discussing signs [signis] I wish it understood that no one should consider them for what they are but rather for their value as signs which signify [significant] something else. A sign [signum] is a thing [res] which causes us to think of something beyond the impression the thing itself makes upon the senses. Thus if we see a track, we think of the animal that made the track.51

Like Dionysius, Augustine does not say that the sign is simply the nomination of something, but that it is composed of a “signified” (for example, the animal) and also of the “impression the thing itself makes upon the senses.” Here we have the rudiments of a tripartite structure: the implied idea of a signifier is separated from a signified, and both are parts of a whole idea called the sign. This tridimensional pattern, like its parallel in Saussure’s Cours, explains a conception of the “impression” that offers a clear alternative to the coalescence of image into referent that constitutes the symbolic structure of metaphor.52

But in the remaining pages of De doctrina Christiana Augustine argues for the necessity of discovering that all signs lead to one univocal meaning, and thereby he moves away from the tripartite structure of the sign and toward symbolism. Proceeding to describe “natural signs” (signa naturalia) as those that are not made with “any desire or intention of signifying,” Augustine contrasts “conventional signs” (signa data), which are made for the express purpose of conveying the intention of whoever made them.53 He then identifies the signs in Scripture as “conventional” because they bear the intention of the Maker conveyed through prophets and evangelists.

Conventional signs are those which living creatures show to one another for the purpose of conveying, insofar as they are able, the motion of their spirits or something which they have sensed or understood. Nor is there any other reason for signifying, or for giving signs, except for bringing forth the transferring to another mind the action of the mind in the person who makes up the sign. We propose to consider and to discuss this class of signs insofar as men are concerned with it, for even signs given by God and contained in the Holy Scriptures are of this type also, since they were presented to us by the men who wrote them.54

With the distinction of certain signs as intentional objects, in contrast to natural objects, Augustine involves in his argument the idea of “use” that Aquinas referred to in article 9. The term reflects the principle, which runs throughout the De doctrina and medieval exegesis as well, that the signs in Scripture are not simply to be “enjoyed” for their own sake, but are to be “used” for the sake of uncovering the spiritual intention of God in them. Although certain signs, “literal” ones, are used with clear intentions, others, “figurative signs,” are more difficult. “Figurative signs occur when that thing which we designate by a literal sign is used to signify something else; thus we say ‘ox’ and by that syllable understand the animal which is ordinarily designated by that word, but again by that animal we understand an evangelist, as is signified in the Scripture, according to the interpretation of the Apostle, when it says, ‘Thou shalt not muzzle the ox that treadeth out the corn.”55 The ox in this text is a conventional sign, according to Augustine’s category, because its meaning is understandable from a familiarity with the broader intentions of Scripture. But the lack of knowledge of those conventions leaves the figurative sign to be read either “literally” or else in any number of arbitrary and erroneous identifications. Furthermore, ignorance of things in the natural world is also the potential of arbitrary interpretation, and Augustine therefore exhorts his readers to study “the nature of animals, or stones, or plants, or other things which are often used in the Scriptures for purposes of constructing similitudes.” Paradoxically, “natural signs,” which have no “intention of signifying,” are also “conventional” because they convey the intention of signifying the universal meanings of God.

Thus the well-known fact that a serpent exposes its whole body in order to protect its head from those attacking it illustrates the sense of the Lord’s admonition that we be wise like serpents [Matt. 10.16]. That is, for the sake of our head, which is Christ, we should offer our bodies to persecutors lest the Christian faith be in a manner killed in us, and in an effort to save our bodies we deny God. It is also said that the serpent, having forced its way through narrow openings, sheds its skin and renews its vigor. How well this conforms to our imitation of the wisdom of the serpent when we shed the “old man,” as the Apostle says, and put on the “new” [Eph. 4.22-25]; and we shed it in narrow places, for the Lord directs us, “Enter ye in at the narrow Gate” [Matt. 7. 13]. Just as a knowledge of the nature of serpents illuminated the many similitudes which Scripture frequently makes with that animal, an ignorance of many other animals which are also used for comparisons is a great impediment to understanding.56

With this passage the tripartite structure of the sign has disappeared; for Augustine has set down the rules for reading physical things as words in the Book of nature : the “snake” has been transformed from the sign that began book 2 into a metaphor. The idea of the sign as an “impression” that occasions the search fo r truth has been replaced by an image that is an object in its own right imitating or miming a signified meaning already well known at the outset. Although Augustine is not saying that divinity is present in the snake (as we find, for instance, in Egyptian fertility myths), he is insisting that the signified precept of God-of shedding the old ways of cupiditas to put on the new virtue of caritas-is present in the image. By this move Augustine has changed the natural object, which he says has no intention, into the position of the conventional sign, which is rich with significance, and the result is the affirmation of a natural bond-a symbolic structure-between the signified and what signifies it.

The ideas about the linguistic sign that emerge from Augustine’s treatise and that were to have a profound influence on subsequent theory, such as Aquinas’s, compare substantially with several of the assumptions we have seen governing the tradition of grammatica: the conventional, rather than the natural, origin of language; its dislocation from a source or object of meaning; its inability to be the language of Adam-the mythological “one tongue” spoken before Babel. And yet hermeneutic approaches to language, like grammatical ones, attempt to reconcile these linguistic facts to a desire to preserve or recapture the natural representation of meaning, and thus they perpetuate past models by continuing appeal to the auctores of linguistic history. Excursions into the various “ways of signifying” in both grammar and hermeneutics remain committed to a more overriding interest in stabilizing signification. While this interest may be understood to a certain extent with reference to the symbolic reading of signs, it ought to be explored as well through consideration of how theoretical positions inform the practice of writing about signs and language. Such exploration, of course, is not limited exclusively to exegesis, as we will see in due course; but for now the step from theory to practice may be taken within the tradition of hermeneutic writing-and in this case an example is conveniently supplied again by Augustine in the Confessions. He began and completed the work during the span of years when he was also laboring over the theoretical study of reading in De doctrina Christiana. Since Augustine confronts in the Confessions the problem of language as a man-made convention, it will be helpful to see how he reconciles it with God’s writing in Scripture-as well as with his own writing in the Confessions itself.

No reader leaves the text without feeling for it some of the lure and pleasure that Augustine himself initially expresses for the seductions of pagan rhetoric and narrative, such as the oratory of Cicero and the Aeneid of Virgil. The irony of this situation of reading must have been felt by Augustine, too, since he spells out rather plainly in the early books the story of himself as a young boy first beaten into learning grammatica-overcoming its various deceptions- and then seduced into the desire to set it and all pagan literature aside in favor of reading and writing about Scripture (the exegesis of Genesis that begins when he leaves off the story of his life, books 10-13). As modern scholarship has become increasingly aware, Augustine’s reflections on language in the book constitute an extensive meditation on the separation of God from man.57 The whole argument about the deception and distraction of rhetoric is an indication of the frustration the young Augustine felt in attempting to understand the transience of all earthly ventures, even intellectual exercises, in perfecting rhetorical skill; for language is a vivid instance of the temporality of worldly affairs. “Our speech,” he says in book 4.10, is “accomplished by signs emitting a sound [per signa sonantia] ; but our speech would not be whole [totus] unless one word pass away when it has sounded its parts [partes suas], so that another may succeed it [succedat].”58 The necessity of temporality, illustrated here as one word or one life must succeed another, is a constant reminder of the value of seeking the Verbum that will not pass away.

The frustration of linguistic distraction, compared throughout the early books of the Confessions to the seductions of the flesh, is relentless until Augustine meets Ambrose, who teaches him how to read the Scriptures figuratively for their moral and anagogical truth. This kind of reading, an ability to see beyond the material appearance of letters to their sources of meaning, is figured for Augustine in Ambrose’s “silent reading”: “But while he read, his eyes passed through the pages, and his heart sought out the sense, but his voice and tongue were silent” (“vox autem et lingua quiescebant”; 6,3).59 It is this exegetical reading in silentio that will ultimately capture Augustine’s attention and determine the kind of writing he himself undertakes in the final three books of the Confessions. But for the moment and until the death of his mother (book 9), Augustine must face the mystery of the “silent writing” in the heart and in God’s Book that is demanding from him some form of audible or written speech. The gap seems unbridgeable at certain points, since his own language reminds him of his difference from the divine Verbum. In book 7, he hears God’s voice in the Psalm, “I am the food of strong men” (Ps. 39.11), but he is thrown back into renewed awareness of his own limitation in the “region of dissimilarity” of this world.60 His utterance, his regio dissimilitudinis, must accept the “unlikeliness” of its own mode and find a means of “becoming like” God’s Word.

The death of his mother brings him closer than he had ever been to an imitation of God’s silent will. In the mysterious deathbed colloquy with his mother, every “tumult of the flesh” (“tumultus carnis”) is silenced-“silenced, too, the … fancies and imaginary revelations, every tongue, and every sign” (“sileant … omnis lingua et omne signum”); no “tongue of flesh” (“lingua carnis”) nor even the “obscurity of a similitude” (“aenigma similitudinis”) gets in the way as they “were talking thus” (9.10).61 Confronting outright the irony of speaking and writing about silence, Augustine seeks a means of avoiding further confused wandering in the regio dissimilitudinis. He recognizes fully the separation between the text that the angels read “without the syllables of time” (“sine syllabis temporum”) and his own noisy, distracted reading.62 But he is led irresistibly toward that Book, toward the discourse that Ambrose, like the angels, read in silentio and that he now reads with Monica. As Augustine moves away from worldly excess and toward spiritual renewal following book 11, the deathbed colloquy becomes the means for solving the riddle of how he can write about God’s silent Word entering his own life.

He begins book 11.2 with phrases that were to fall like potent dyes into the history of medieval writing about writing. Excess is still a powerful motion of his soul, and he is troubled by how he will ever “suffice with the tongue of my pen to express all” (“lingua calami enuntiare omnia”; 11.2).63 To direct the passion for fulfilling desires away from fleshly ends, he requests the capacity for a new chaste and virginal utterance: “Circumcise my interior and exterior lips from every temerity and every lie. Let your Scriptures be my chaste delights” (“Circumcide ab omni temeritate omnique mendacio interiora et exteriora labia mea. Sint castae delicae meae Scripturae tuae”).64 Perhaps Bernard of Chartres was thinking of this text in the Confessions when he reflected on the status of pristine meaning as an undefiled virgin who is gradually corrupted when the substantive is differentiated through syntactical arrangements. We do not know for sure. But it is obvious in Augustine’s passage that God’s discourse is unmediated, a natural-“chaste” -state of meaning. He begins to solve the dilemma of speaking about the unspoken will of God in his own life by redirecting his attention away from himself and toward God’s words in Scripture.65 And yet, since they are the records of human writers, he must begin with a meditation on how he can get back to the paradise of the divine Verbum through the mediation of the created and temporal syllables of the Bible.

With “circumcised” lips and tongue, he poses the first question the nature of God’s utterance at the moment of Creation: “But how did you speak?” What was the “manner” (“modo”) of it (11 .6)?66 Like the later grammarians, Augustine is motivated by fundamental questions concerning the “ways of signifying,” though he has much more metaphysical weight to carry in the Confessions. If God spoke in Hebrew, Augustine would listen in vain since he did not know the language; yet he says that he would nevertheless understand the divine utterance “in the chamber of my thought,” where it would be heard “without the organs of voice and tongue, without the sound of syllables” (11 .3).67 But the limitations of human comprehension cannot adequately reflect how God’s utterance at the Creation was spoken and understood. For even the voice that said “This is my beloved Son” (Matt. 17.5) “was uttered and passed away, began and ended” until there was silence after the last syllable (11 .6).68 A creature had to say and hear these words, but the creating Verbum had to precede both. When it was spoken, Augustine continues, the outer ear reported the words sounding temporally to the inner ear of the understanding mind; listening to the eternal, the ear of the mind then said: “Aliud est, longe aliud est” (“It is different, it is far different”; 11.6).69 The creating word asserts a separation between itself and the words by which it is spoken: it is self-differentiating. But so are Augustine’s spoken and written words. While the “ear” is “speaking,” he goes on to say that the temporal words spoken at Creation (“these words”) are “below me,” and God’s Word is “above” -yet with this sentence, Augustine implicates the temporal words that he writes; his own utterance is self-differentiating. (“Haec longe infra me sunt; nec sunt, quia fugiant et praeterunt: Verbum autem Domini mei supra me manet in aeternum”; 11.6).70 At the same moment as Augustine asserts the separation of divine from human discourse, he draws his own writing into parallel with the creating Verbum: while there is nothing similar in essence between them, the first nonetheless is profoundly involved in the second by virtue of the differentiation that both carry out. The strategy through which the text comments on itself occurs at various points when Augustine speaks of haec verba, but it is particularly emphatic in the interrogative mood, with which the chapter closes: “By what word of yours was it announced that a body might be created, from which these words might be created?” (“Ut ergo fieret corpus unde ista verba fierent, quo verbo a te dictum est?” 11.6).71

The metaphorical conjunction here between corpus and verba is hardly accidental. It suggests the parallel of his writing with (the incarnational Verbum that “became flesh” so that saving words might be spoken. Augustine’s verba are becoming the corpus explaining God’s Verbum-an act of writing in which the presence of the word is maintained in the flesh of the letter. It is fitting, therefore, that Augustine proceeds from the question who made the words to a consideration of the continuity of the Verbum in the created world: “For what was spoken was not finished, and something else spoken so that all things could be spoken” (“neque enim finitur quod dicebatur, et dicitur aliud ut possint dici omnia”; 11.7).72 Conceiving of creation as a concatenation of utterances proceeding from the first Word, Augustine links the human word- specifically his expression at the opening of book 9.8-with divine origin. “How I shall express it I do not know,” he says (“sed quomodo id eloquor nescio”; 11. 8), since everything begins and ends. But nothing begins or ends except as it “is known in eternal reason” (“in aeterna ratione cognoscitur”; 11.8). That ratio “is your Word-your Beginning-and it speaks to us” (“Ipsum est verbum tuum, quod et Principium es quia et loquitur nobis”; 11.8).73 The Principium, he concludes, continues in what has been made, just as Jesus, the Verbum, spoke in the gospel after the creation of the world; his word was spoken as ours is- “through the flesh; and it was heard abroad by the ears of men” (“per carnem ait; et hoc insonuit foris auribus hominum”; 11.8); yet still “he is the Beginning and speaks to us” (“quia Principium est, et loquitur nobis”; 11.8).74

Although the primordial creation is a moment of profound differentiation, the created world and words of Augustine endure not a breach but an expansion from their origins of meaning.75 The words of Scripture and its exegesis in the text of the Confessions cannot body fo rth the timeless presence of the Verbum-“no time can be totally present” (“nullum vero tempus totum esse praesens”; 11.11),76 but the traces of that original presence are before us as Augustine turns the Word of his experience of God’s will into the flesh of the words-the corpus-of the Confessions. Leaving off the story of his life in the flesh, he takes up the explication of Genesis with “circumcised” tongue as a new effort in the redemption of fallen discourse. The practice of hermeneutics is the project through which “the obscure secret of so many pages should be written” (“scribi voluisti tot paginarum opaca secreta”; 11.2); it is instituted as a recuperation of the lost origin and plentitude of God’s meaning.77 Augustine may be limited by the “syllables of time,” but the project he begins is committed to seeing the Book read by the angels reflected in the Scriptures read on earth. “Your Scripture is spread abroad over the people, even to the end of the world” (13.15).78 Although he does not dissolve all differences between the two texts, his hermeneutics is surely devoted to illuminating the dark likeness between them. By conceiving of his own interpretive writing as the gradual manifestation of an original Word-a Principium that has no end-Augustine illustrates in the Confessions what he says about reading in De doctrina Christiana-that signs are ultimately informed by the controlling law of caritas. Given the authority of Augustine for later writers, it is not difficult to see why language theory, in spite of its complexity in hermeneutics and grammatica, did not give birth to radical departures in the modes of signification.

Augustine’S influence on the institution of interpreting the Bible in the middle ages must not be underestimated; but it would be wrong to assume that he was its primary magister controlling all later developments. Yet in view of the preoccupation with validating meaning by appeal to a source-be it an original language or text in the hermeneutic tradition or a given linguistic model in the grammatical tradition – language theory in the middle ages was fertile soil for interpretation to take root among various authors, as it does in the final books of the Confessions: subsequent exegesis also validates its own mode by appeal to an original text – the Bible itself, the Book in the sky, or an authoritative auctoritas, such as a work by Augustine. Although these medieval strategies of signifying are a long way, both in time and in composition, from Egyptian and Sumerian myth, the structure of thought pars pro toto has not been completely abandoned.79 The fate of the linguistic sign in the middle ages seems to correspond to that of its spatial counterpart: the effort to break away from precedent structures turns out to repeat or supplement some aspect of them. In this case, both the spatial and the linguistic sign function within, rather than call into question, the larger structure of medieval mythologizing that includes them. One way to consider further the nature of this mythology in medieval hermeneutics is provided by the noted argument of Erich Auerbach concerning the difference between the styles of biblical writing and the styles of myth, as represented by the Homeric poems. Auerbach’s contrast is not without certain weaknesses of generalization: Homer’s texts do not entirely exemplify a style “of the foreground,” and the biblical documents, which were written over many centuries and which reflect different cultural influences, are not exclusively “of the background.”80 But the value of the contrast need not be judged by the application of these two categories to every detail of style in each of the two literary texts; rather, the importance may consist in the link between a particular kind of thought and the style of writing it produced: the “fore grounded” style of myth seems to be of a piece with the immanence of divinity in signs-the logocentric presence of meaning. In contrast, Hebrew writing “of the background” reflects a sense of the abstraction and transcendence of the divine order, an understanding of the essential secrecy and mystery of divine meanings, and an appreciation of their absence from the writing that tries to render them intelligible.81 Medieval interpreters of the Bible were certainly well aware of the difference, but it is not always preserved in their own styles of writing, and where one style slides into the other, the earlier mythological form of signifying has left its mark on the course of the medieval hermeneutic project. This determination may be studied by taking a close look at a biblical text and then considering whether the medieval interpretation of it has anything to do with the “foregrounding” interest of mythology.

The Document of the Davidic Succession (2 Sam. 9-20; 1 Kings 2) offers a challenging test of Auerbach’s view of the unmythological style of biblical narrative because it is older than the work of the Elohist and was written at a time (in Solomon’s reign) when Israel was very close to her mythological neighbors. Although in this document the Hebrews first explained their sense of kingship and dynasty, they did not emulate the elaborate myths of the Egyptians and Babylonians whose kings were deities and whose monarchies replicated the kingship of the gods. Beginning with the dilemma that the queen is barren, the record raises the question of the king’s successor, but it does not provide God’s choice or even his will about the matter. Events proceed in the chronicle “as they occurred.”

It happened towards evening when David had arisen from his couch and was strolling on the palace roof, that he saw from the roof a woman bathing; the woman was very beautiful. David made inquiries about this woman and was told, “Why, that is Bathsheba, Eliam’s daughter, the wife of Uriah the Hittite.” Then David sent messengers and had her brought. She came to him, and he slept with her; now she had just been purified from her courses. She then went home again. The woman conceived and sent word to David, “I am with child.” (2 Sam. 11.2-5)

Whereas in Genesis we find at least some expression of Adam’s fear and hear the divine judgment upon him, the absence of subordinating information in the account of David creates a sense of the matter-of-fact about an incident that is anything but a matter of simple fact. David’s predicament has vast political and religious significance, but it remains unexpressed. The one possible remedy -to send Uriah home from the battlefield to sleep with his wife backfires when Uriah refuses out of his sense of loyalty to the king. “Are not the ark and the men of Israel, and Judah lodged in tents; and my master Joab and the bodyguard of my lord, are they not in the open fields? Am I to go to my house, then, and eat and drink and sleep with my wife? As Yahweh lives, and as you yourself live, I will do no such thing!” (2 Sam. 11.11). The impact of what is not being said in these lines creates a feeling for the unexpected that eventually results in murder. The question of Uriah has the same rhetorical effect as the famous ironic question of Isaac. And as Isaac does not know that he himself is “the lamb for the burnt offering,” Uriah’s innocence of heart and his simple faith in his king prevent him from ever suspecting the adultery of his wife and the dishonesty disguised behind the king’s favor. At the end of the account, all we are told is: “What David had done displeased Yahweh” (2 Sam. 11.27).

The reluctance to justify David’s behavior and express the divine judgment on him is evidence of the crucial difference between the Hebrew monarchy and Near Eastern mythologies of divine kingship. Studying the theology of this difference, Gerhard von Rad observes that the “Anointed” of Israel is clearly not a deity like Pharoah, nor is he especially pure, nor is his office intrinsically sacred. Unlike the monarchies of Egypt and Babylon, the Davidic dynasty did not “‘come down at the beginning from heaven.’ In this respect no mythic dignity of any kind attaches to it.” The assumption of the presence of the divine order in myth is contrasted sharply to the premises of the Hebrew document. What Auerbach says of Genesis- “Everything remains unexpressed” -is paralleled nearly exactly by von Rad’s remarks on the style of the Succession Document: “The narrator only once draws the curtain back and allows the reader for a moment to perceive the divine power at the back of what appears in the foreground …. This historical work was the first word spoken by Israel about Yahweh and his anointed in Jerusalem; and it is an absolutely unmythological word. This realism with which the anointed is depicted, and the secularity out of which he emerges and in which he moves, are without parallel in the ancient East.”82 By refusing to foreground the nature and reasons of the divine will, the styles of Genesis and the Succession Document do not tend toward the metaphor of writing that replicates divinity. Rather, speaking about a God who made “Darkness … a veil to surround him” (Ps. 18.11), the styles of biblical narratives are “demythologizing.” Zeus is “comprehensible in his presence,” and to touch Pharoah is to touch Ra; the Egyptian mother goddess Nutt is present in the sky, and the Mesopotamian deity Ahamash is known in the sun; Baal is immanent in the storm and Poseidon in the sea. But the Hebrew God, as Henri Frankfort has commented, “is pure being, unqualified, ineffable.

He is holy . . . all values are ultimately attributes of God alone. Hence all concrete phenomena are devalued …. Nowhere else do we meet this fanatical devaluation of the phenomena of nature and the achievements of man: art, virtue, social order-in view of the unique significance of the divine …. Only a God who transcends every phenomenon, who is not conditioned by any mode of manifestation-only an unqualified God can be the one and only ground of all existence. This conception of God represents so high a degree of abstraction that, in reaching it, the Hebrews seem to have left the realm of mythopoeic thought. “83 In contrast to deities who exist in the foreground, are immanent, Yahweh’s nature is not revealed in the burning bush (Exod. 3.1 -6) or the acts of David. The sign tells us nothing about the nature of the signified. The Hebrews speak of a God who is not known in idols but who is always “at hand” in the background – imminent. The signs about him do not tell us what he is, only that he is. All we hear in the episodes of Isaac and Uriah as the divine voice is an echo of a never-present totality, a sudden irruption that is only an accidental and arbitrary means by which Yahweh lets himself be known.

When we turn to the pages of medieval hermeneutic practice, the profound sense of background that characterizes such biblical texts as Abraham and Isaac or David and Bathsheba is not always maintained. Auerbach has observed this point as a general characteristic of Augustine’s commentaries on Scripture, for instance, in the Civitas Dei, and his observations may serve as a preface to the nature of style in the many commentaries that followed Augustine. “There is visible,” says Auerbach of the Civitas Dei,

a constant endeavor to fill in the lacunae of the Biblical account, to supplement it by other passages from the Bible and by original considerations, to establish a continuous connection of events, and in general to give the highest measure of rational plausibility to an intrinsically irrational interpretation. Almost everything which Augustine himself adds to the Biblical account serves to explain the historical situation in rational terms and to reconcile the figural interpretation with the conception of an uninterrupted historical sequence of events. The element of classical antiquity which asserts itself here is also apparent in the language – is, indeed, more apparent there than anywhere else; the periods … make no impression of great art … but with their abundant display of connectives, their precise gradation of temporal, comparative, and concessive hypotaxes, their participial constructions, they still form a most striking contrast to the Biblical passage cited, with its parataxis and lack of connectives. This contrast between text and Biblical citation is very frequently to be observed in the Fathers and almost always in Augustine …. In such a passage as this from the Civitas Dei, one clearly recognizes the struggle in which two worlds were engaged in matters of language as well as in matters of fact.84

This insight merits careful consideration in the study of medieval hermeneutics. As forthrightly as Augustine opposed pagan habits of thinking and writing, his interpretive procedure does not finally establish a firm boundary against them. The “two worlds” that converge in his work are also two fundamentally opposed ways of signifying meaning. They are as old as Abraham’s departure from the religions of Ur and as consequential as the difference between the sign that is the embodiment of its signified reference and the writing that is fraught with the background of the abstract and transcendent. If Augustine’S brightly illuminated form holds on to the past, so also may the writings of many of the commentators he influenced. Perhaps they too, as Auerbach claims, “fill in the lacunae of the Biblical account” and create a form not unlike the mythologized style that stands out as a “most striking contrast to the Biblical passage cited.” To examine this possibility, I would like to return to the story of David and Bathsheba and consider a typical medieval interpretation of it, for instance, one recorded in the Glossa ordinana.

In this commentary, we find the record of a lengthy dialogue between the lovers that is revealed for the exegete in the mention of only one word, concepi (2 Kings 11.5), Bathsheba’s confession that she is pregnant.

The pregnant woman goes to the king and says: “0 king, I have been undone.” And he says to her: “What is the matter?” “I am pregnant,” she says. “The fruit of my sin grows, and inside I have the cause. In my womb I am making the betrayer. If my husband comes to me and sees, what will I say? What will I tell? What excuse will I put forward?”85

Hardly an enigmatic figure, Bathsheba is almost less important than the frustrations, fears, and thoughts that are seen brightly illuminated and delineated by her. A context of motives behind David’s questionable behavior is just as vividly in the foreground as the few details indicating that he was on his balcony “when kings go forth.” For whatever reasons David did not go with his army to meet the enemy, exegetes saw otiositas, too much “idleness” or “leisure,” as the explanation for his acts; the old sententia from elsewhere in the Bible, “the devil finds work for the idle hands,” and from Seneca, “summa omnium vitiorum otiositas,” are also clearly intended by the scriptural passage according to the Glossa, which includes them between the lines of the quoted text in the “interlinear gloss” and on all four sides of it.86 Not only does the Glossa add details to the text-namely, that David was strolling about his balcony, looking out of a window and gazing eagerly at Bathsheba bathing in the nude-but further, Gregory and Rabanus take us on a virtual tour of David’s inteThe biblical narrative makes no attempt to explain away the ironic aspects of events, but exegesis, like myth, refuses to tolerate irony: all events are fitted into a highly systematic and self-explanatory scheme. The overbearing irony of the entire narrative-that the king of Israel has to stoop to murder because of the devotionrnal being, pointing out the image of Bathsheba imprinted on his mind as a primary cause of the “filth of thought” (cogitationis immunditia) inducing oculorum illecebra, an “enticement of the eyes” that ineluctably provoked David’s soul to concupiscentia and his flesh to luxuria.87 The ideas “behind” the events clearly have greater reality than the events themselves. That the baby conceived by Bathsheba dies suggests that God punished David for adultery by “taking” his child, but the comment in the Glossa elicits from this mere suggestion an elaborate conclusion surely informed by medieval morality. “Truly, those who were born after him [the dead child] God did not kill, because David married that woman.”88 The crucial difference between the text and the comment is the generalization that the child dies because David and Bathsheba were not married: what is simply suggested as a result of the incident is made by the exegete into its primary cause. One implication, among many possibilities in the text, is totalized into a precept about marriage.

The biblical narrative makes no attempt to explain away the ironic aspects of events, but exegesis, like myth, refuses to tolerate irony: all events are fitted into a highly systematic and self-explanatory scheme. The overbearing irony of the entire narrative-that the king of Israel has to stoop to murder because of the devotion and chastity of one of his lowly soldiers-is no contradiction in the Glossa. For Bathsheba is a type of the “well of living water,” puteus aquae vivae (because she is associated with water imagery in the narrative), David is a type of Christ because he is king of Israel, and Uriah signifies the Jewish people. As a type of the well, Bathsheba is identified with Ecclesia, which was carried as the ark by the Jews until that “marriage” was broken by Christ. David – “appearing as the Redeemer in the flesh” -took away “by strength of hand” (manufortis) that “wife” from her former “husband” dedicating her to a new life of the spirit, no longer bound to the letter of the law but “conjoined” (conjunxit) to a new spiritual “husband.”89 The exegete is not really interested in righting David’s wrongs but focuses on the apparent conflict, for it reveals that even in an event reprehensible in itself God was giving “signs” to future generations about the superiority of Christianity to Judaism. The immorality is less important than the preoccupation to see common themes illustrated in new ways. In this case the union of Christ and the Church, God and the soul of man by virtue of their unifying bond, caritas, is totalized in the text. While these meanings are not “literally” present, neither are they hidden in the distant background; from the medieval point of view, they were written “with Goddes fynger.”90

In these examples, the nature of the linguistic sign is hardly arbitrary. As one commentator has observed, the sign is a “copy” that has the “magical ability to focus … reality and bring it into view.” Another commentator, E. H. Gombrich, has argued a similar point, maintaining that such signs have their roots in the mythological cultures of prehistory; few have recognized, he argues, that “Western literature and art have preserved the peculiar habits of the ancient world to hypostasize abstract concepts. “91 As the medieval “habit” of reading is determined to reveal, clarify, and make present scriptural meanings, it too hypostasizes an imminent and transcendent order. And what is true of a sign in the Succession Document is true of the medieval sense of history in general: an event in David’s reign could be “read” in the Tree of Jesse, for instance, in the window of Chartres cathedral just as it was “written” in the past of ancient Israel. In these interpretive exercises, performed on Scripture or on nature, the organicism of mythology is in full control of the metaphor of writing.

For all their color and invention, the brightly illuminated glosses in the texts of Augustine or the windows of Chartres are not made explicitly in the service of advancing an order of speculative and abstract thought that might be associated with the discipline of philosophical theology. But although medieval hermeneutic practice may lack the “vocabulary” of abstract reference, it nonetheless possesses the “grammar” for it. In the determination to answer authoritatively and thoroughly the questions and doubts, the gaps and lacunae of biblical writing, exegesis carries out a function analogous with that of myth, as argued in recent theory, to mediate contradictions and uncertainties in a society, not to doubt things, but “to talk about them; simply, it purifies them, it makes them innocent, it gives them a natural and eternal justification, it gives them a clarity which is not that of an explanation but that of a statement of fact … it organizes a world which is without contradictions.”92 Such concerns may not proceed in the language of abstract inquiry, but they obviously engage problems of a very high order of thought. Turning, for example, to the sacrifice of Isaac, the background of mystery and doubt apparently did not draw the attention of the medieval exegete, from what we can tell by the popularity of the following gloss:

Abraham ergo Deum Patrem significat, Isaac Christum. Sicut enim Abraham unicum et dilectum filium victim am Deo obtulit, sic Deus Pater unigenitum Filium pro nobis tradidit. Et sicut Isaac ligna portabat, quibus imponendus erat, sic Christus crucem, in qua figendus erato

[Abraham therefore signifies God the Father. Isaac signifies Christ. Just as Abraham offered to God his only beloved son as a victim, God the Father surrendered for us his only begotten Son. And just as Isaac carried the wood, on which he was to be laid, so also did Christ carry the cross on which he was to be fastened.]93