Slavery in Renaissance Europe was very much an urban phenomenon.

By Dr. Kate Lowe

Professor Emerita of Renaissance History and Culture

Queen Mary University of London

Introduction

The first questions are: Who were the slaves in Europe in the Renaissance and where did they come from? Was there a change over time in the period from 1400 to 1600? There were two main routes by which enslaved Africans were brought to Europe: from the eastern Mediterranean or North Africa, and from the west coast of Africa. But, with the exception of Spain, in the mid-fifteenth century before the commencement of the slave trade from West Africa, only a small percentage of slaves in Europe were African; the vast majority were from the eastern Mediterranean, Russia, or Central Asia. During the Renaissance, slavery was not just a black phenomenon—slaves in Europe were both “white” and “black.” Europe had a long history of white slavery. There was mass white slavery in Europe before there was black slavery,1 and white slavery continued after the influx of black slaves from sub-Saharan Africa in the fifteenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth centuries, so that often white and black slaves worked alongside each other in the same households or on the same properties. Because of its ancient settlement and diverse civilizations, European society in the Renaissance was fractured and complex, and this had consequences for the variety of ways in which slavery developed.

Slavery in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Europe was usually not for life; instead, on the death of a master or mistress, either a slave was freed or a set period of further enslavement was fixed. In Europe, a future freed life for slaves was envisaged, and consequently slaves always lived in hope that they would be freed from bondage. Manumission, or the freeing of slaves, was a distinct probability. The mechanism for this was normally contained in a will, where futures for slaves were mapped out, and where money was bequeathed for marriage, for setting up house, or for enabling a former slave to make a living. Clothes and possessions were also bequeathed. At its simplest and smoothest, therefore, slavery in Europe during the Renaissance can be seen as just a stage in a life and not a life sentence. As a result of this process of being freed within a generation, and of having the possibility of integration, freed and free Africans were socially mobile and very quickly appeared in professional and creative positions in Europe. The late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries saw the first black lawyers, the first black churchmen, the first black schoolteachers, the first black authors, and the first black artists.2 Superficially at least, the black African depicted in European dress by Jan Mostaert (see fig. 1) had been “Europeanized” through his acquisition of European accessories such as a sword and the hat badge from a Christian shrine, and he may have been an ambassador or held a position at a European court.3 The son of a black African slave couple in Europe in this period even achieved sainthood: the first black European saint, San Benedetto (St. Benedict, known as “il moro” or the Moor) lived in Sicily in the sixteenth century, although he was not canonized until 1807.4 “Moor” is an imprecise word that in the sixteenth century had been divested of its original religious meaning of a Muslim, to become a generic word most usually applied to an African or someone from the Ottoman empire. The word does not carry any indication of ethnicity or skin color: rather, further descriptors labeled people as white moors, brown or tawny moors, and black moors.

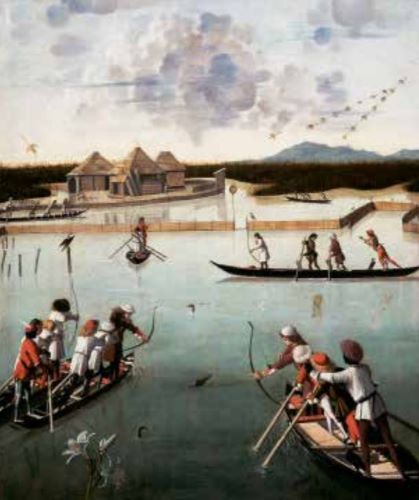

The practice in Renaissance Europe of manumitting slaves during their lifetimes had important consequences for the representation of Africans in whatever media in the Renaissance. Although African—especially black African—attendants and bystanders in European depictions (except in some parts of Northern Europe) are usually assumed to be slaves, in most cases legal status is not apparent and cannot be discerned from an image. In Venice, a niche occupation for freed black Africans existed, linked to their prior skills as slaves, and possibly also to their prior lives in West Africa: that of gondolier.5 Two iconic Venetian Renaissance paintings, Vittore Carpaccio’s Miracle of the True Cross at the Rialto Bridge, also known as The Healing of the Possessed Man, of 1494, which includes two black gondoliers, and his Hunting on the Lagoon of ca. 1490–95 (fig. 2), which includes a couple of black boatmen, show black Africans at work in water activities, but there is no way of telling whether they are enslaved or free.6 Africans in Renaissance representations could be either slaves, freedmen (that is, ex-slaves), or freemen (that is, people who had never been slaves, but one or both of whose parents probably had been). This latter category could have included people of part-African ancestry, who had only one African parent, of whom within a generation there was a significant number. In most cases, especially in representations of African heads, the legal status of the individual depicted was beside the point; in a few cases, the artist wished to ensure that the viewer understood that the African was a slave, and so included chains, manacles, or a slave collar. A small Italian cast-iron head of a bearded black slave wearing a slave collar from the second half of the sixteenth century (no. 52) is rather surprising, as most depictions of slaves in slave collars, which could be highly decorated, expensive pieces of jewelry, are from a later period. Leg irons and manacles were usually used as a form of punishment after a slave had attempted to run away or when it was suspected that they would abscond if a chance arose; chains were not routinely employed. North African Muslims, some of whom would have been captured in war, were placed in chains more frequently than sub-Saharan Africans.

The German artist Christoph Weiditz from Strasbourg compiled a costume book in the 1520s and 1530s that recorded the dress and habits of people, including slaves, in Spain and the Netherlands. White galley slaves and black slaves loading water onto ships appear wearing leg irons, and a black slave in Castile has leg irons around both ankles and a heavy chain linking one of them to his waist (fig. 3). In the inscription accompanying this last image, it is explained that the chain signifies that the wearer has already attempted an escape.7

Including an inscription or explanatory panel was another route by which artists could ensure that the viewer understood that the African depicted was a slave. For example, the black female slave designated by the label Ethiopissa in a German woodcut illustrating the list of characters in a 1499 edition of Terence’s play The Eunuch (fig. 4) is a slave. Use of the word Ethiops or one of its variations in this period simply indicates that the person is a black African; it does not indicate that the person came from Ethiopia.

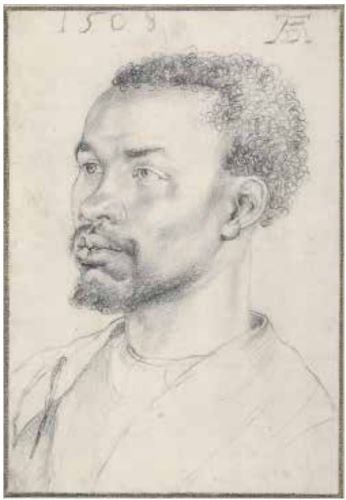

As far as representations of slaves are concerned, ancient historians have isolated factors such as smallness of stature, shortness of hair, and posture of the body that they claim denoted slaves in representations from ancient Greece,8 but it is not possible to do this in Renaissance Europe. Occasionally, the depressed or despairing expression of the African indicates that the person depicted was probably a slave. This is the case with the portrait in silverpoint by Albrecht Dürer of a young black African woman called Katharina (no. 55), whom Dürer encountered in Antwerp in the house of one of his patrons, the Portuguese factor João Brandão. Described by Dürer in his diary as Brandão’s Mohrin, or Moor,9 she was very probably his slave rather than simply his servant, although as we shall see, slavery was not legal in the Low Countries,10 and the word does not convey any legal meaning. Katharina was black, as is shown by Dürer’s drawing, but his diary entry does not make this clear. Dürer himself inscribed the year, her name, and her age—twenty years old—on the drawing, so these are not in doubt. Katharina’s infinitely faraway expression, her downcast eyes, and her hair covering are movingly captured by Dürer. The artist also drew a second black African, a man, at around the same date (fig. 5). Although the date “1508” appears on the drawing, alongside Dürer’s monogram, the date is not considered secure. Nothing is known of this man, and it could be that he is the Diener or servant of the same João Brandão whom Dürer writes he drew after 14 December 1520. With a moustache and beard in addition to close, curly hair, this African is less likely to have been a slave than Katherina, as beards were usually forbidden to slaves, and his expression is less obviously despairing.

The position of the African in a scene visà-vis other humans can also suggest inferiority, as in the case with the young black children who were so prized at European courts, and who were sometimes painted alongside their owners or masters/mistresses, as in Titian’s portrait of Laura dei Dianti of ca. 1523 (fig. 6)11 and Cristóvão de Morais’s portrait of Juana of Austria of 1555 (fig. 7).12 The black boy and girl are considerably smaller than their mistresses, as they are children, and their smallness of stature makes them vulnerable and unimportant.

However, these children were not necessarily slaves, although most of them probably were; sometimes whole black families of free people were lured to the courts to work, in order that suitably young and attractive black children could be available to serve.13 In group scenes involving both white and black people, black Africans often appear in very marginal or liminal positions, but once again this cannot be taken as an indication of legal rather than social status.

The Lives of Slaves

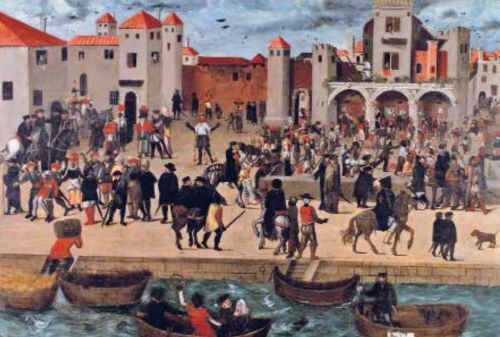

Slavery in Europe was very much an urban phenomenon, and as a consequence, many slaves found themselves living as either the only slave or one of two or three in a household. Households were often composed of both slaves and differing types of servants. Only very occasionally would large groups of Africans have been able to congregate in a European city, but one site in Lisbon provided just such an opportunity. Lisbon had the greatest percentage of black people in Europe at this time, with perhaps 10 percent of the population being black.14 In an anonymous, late sixteenth-century painting of the Lisbon waterfront, a probably Netherlandish artist has depicted the great concentration of black people of all social and legal statuses, from slaves carrying water to petty criminals to knights, to be found around the Chafariz d’el Rey, the king’s water fountain (fig. 8, and no. 47).15 This genre scene is highly unusual, and in addition to providing valuable visual vignettes of Africans at work and at play, it allows the viewer to gain a sense of black and white social and spatial interaction in a setting where blacks and whites appear in roughly equal numbers. Domestic slavery was in most cases the “easiest” form of slavery for men, less arduous and less physically dangerous than other forms of slavery. Like female servants, female slaves were easy sexual prey wherever they worked, although there may have been safety as well as danger in living in cramped conditions. Slaves were owned by a great variety of people living in cities and towns: for example, one study of Valencia found that in the period 1460–80, of 317 slaves, 8 percent were owned by nobles, 8 percent by lawyers and doctors, 25 percent by merchants, shopkeepers and brokers, 11 percent by people involved in the textile industry, 5 percent by those involved in construction, and 4 percent by bakers.16 And in a list of black and white African female slaves shipped from Lisbon and sold in Italy through a Tuscan bank in the 1470s, owners included goldbeaters, leather, wool, and silk merchants, shoemakers, a general manager of the Medici bank, the son of a humanist, and a count.17 In countries where there was a monarch, the monarch often owned a number of slaves, and in the Italian courts, the ruler owned slaves. The conditions of enslavement often depended upon the status of the owner. If a slave was owned by an artisan, s/he lived in part of the artisan’s house and ate food given by the artisan, but if a slave was owned by a king or queen, or nobles, s/he was dressed well, fed well, and housed well. Accounts from the Italian courts include many interesting payments for slave clothes, slave bedding, slave shoes, and slave artifacts. African slaves owned by monarchs and rulers also had access to excellent health care. For instance, the Portuguese queen Catherine of Austria paid for one of her slaves who had a head injury to be treated by her surgeon in 1552.18

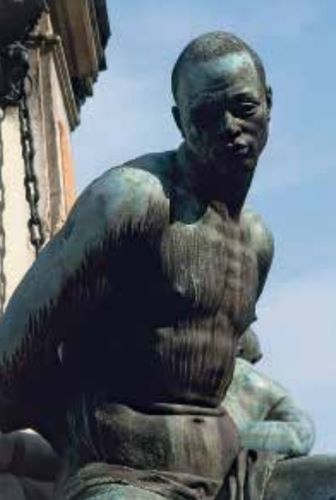

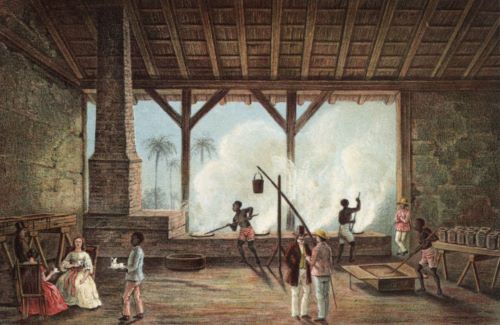

Those African slaves who did not live in urban centers probably had worse lives. A particularly unfortunate, non-urban group of about 125 black Africans was worked to death in the silver mines of Guadalcanal in Andalucia, owned by the crown, between 1559 and 1576;19 although not significant in numerical terms, their fate is a presentiment of the dehumanization later to befall many other enslaved people. In Sicily20 and Madeira, slaves worked as agricultural laborers, some even on sugar plantations,21 in situations that may have been the forerunners of plantation slavery in the Caribbean (no. 45) and United States. Other slaves, both white and black, served on the galleys, some as punishment for a crime, others because they had been taken prisoner in war. Theoretically, most galley slaves too served time-limited sentences, but the life was extremely hard and many died before regaining their freedom. A monument in Livorno commemorated victory over the Ottomans in North African by Ferdinando I de’ Medici, the grand duke of Tuscany in 1607. It was composed of a marble statue of Ferdinando completed in 1599 and of four colossal ethnically diverse slaves in bronze, which were commissioned by Fernandino’s son, Cosimo II de’ Medici, from Pietro Tacca and completed in 1626.22 The Medici developed Livorno as an international port, setting up the huge bagno or depot for galley slaves there, and encouraging settlement by forcibly converted ex-Jews,23 so it was populated by an appropriately diverse population. One of the four chained, nearly naked slaves, known as the Four Moors, on the base of the monument, has black African features (fig. 9), and had been modeled, as had the other three, on real galley slaves.24 The clean-shaven, young black man’s expression is of numbed despair, with worry lines creasing his high forehead. A note authorizing that Tacca take a wax cast of a slave in 1608 specified that the slave must be a well-behaved one (therefore presumably not one with a criminal past).25 Tacca followed classical precedent in assembling the most perfect features from a number of slaves in order to create his statues, so although the representations of these slaves were all taken from life, there were no four slaves whose faces and bodies looked exactly as these figures did.

There are a considerable number of Renaissance representations where rich and influential people are depicted with their families or entourage, including their servants and slaves. Some of these representations were almost certainly of real people, painted or sculpted from life, and these allow us a glimpse into servants’/slaves’ social realities. The image of the black huntsman in the fresco of The Journey of the Magi by Benozzo Gozzoli in the Medici Riccardi palace in Florence of 1459–62 (fig. 10), which is full of portraits of the Medici and their friends and retainers, falls into this category.26 One of the attractions of this very extensive group of likenesses would have been the possibilities of recognition it afforded to contemporaries. The black African is positioned right at the front of the fresco on the east wall, between Galeazzo Maria Sforza, the ruler of Milan, and Cosimo de’ Medici, the ruler of Florence, both of whose portraits would have been instantly recognizable. At the time, the black African would probably have been recognizable too, although no black Africans have as yet been found in Cosimo’s household or employment. The face and head of the huntsman are strikingly rendered, with tight, very short curls, high and deeply angled cheekbones, wide nose, light moustache, and full lips; he is dressed in a turquoise tunic with multicolored hose, and holds a large bow but no arrows.

Rather than being likenesses, other representations involving master and slaves were not based on actual slaves but on imagined, generic, or impersonal slaves, with composite features or unstable African attributes, such as a turban. These, in their turn, allow us to see a different aspect of the Renaissance attitude toward slavery. In the marble bust of 1553 attributed to the workshop of Leone Leoni (perhaps by Angelo Marini), the severe and imposing Milanese judge and senator, Giacomo Maria Stampa (no. 43), is supported by two semi-naked figures known as atlantes, one wearing a turban.27 The occupation and pose of these human pillars make it likely that they were supposed to represent slaves. Atlantes were a relatively common type of slave representation at the time, but the features of the atlantes themselves were imagined rather than “real,” in contrast to those of the black huntsman. Even if it is merely a stylistic issue, Stampa is here represented as a higher mortal, whose likeness is worthy of being remembered, held aloft by two straining lesser beings of no consequence.

Even when freed, it would have been almost impossible for most sub-Saharan former slaves to return to their country of origin. Exceptions to this rule are provided by some of those taken on the first voyages by the Portuguese, who trained them as translators in Lisbon and took them back on subsequent voyages to act as interpreters for them,28 and some of those taken on the first English voyages, who stayed a period of time in England, probably to learn English, and then were taken back. Five Africans from Shama on the coast of what is now Ghana were taken to London in 1554–55. They were returned in 1556, and were greeted with much joy, especially by the wife of the brother of one of them, and by the aunt of the same person.29 Returning home was, however, a possibility for North Africans, especially from Spain, which was very close to North Africa; one study identified 330 freed moors who emigrated back from Valencia in Spain to Islamic territories between 1470 and 1516, paying an exit tax in order to leave.30 There is also the famous case of the Muslim travel writer al-Hasan ibn Ahmad ibn Muhammad al-Wazzan, known as Leo Africanus in Europe (see Davis, pp. 61–79), who was captured, enslaved, and converted to Christianity under Pope Leo X in the second decade of the sixteenth century. As soon as the opportunity arose, he returned to North Africa after years in Europe.31

It is important to consider the types of collective activities available to African slaves. In some parts of Europe, Africans were able to fight their masters through the courts (for example, in Valencia they could appeal to an official called the Procurator of the Wretched), and a surprising number were successful.32 In Portugal, Spain, and Italy, they also could belong to confraternities,33 which were social groups backed by the church devoted to good works, some of which were all-black, and were heavily engaged in buying the freedom of black slaves.34 There were, in addition, parishes in Portugal and Spain where a significant number of African people lived, which must have facilitated more of a sense of collective identity. The worst threat was to say that a slave would be sold away from his or her familiar surroundings—in mainland Spain, difficult slaves were threatened with being sent to Ibiza35 or Majorca, and in Portugal, slaves were brought to heel by the prospect of being sold in Spain. Collective slave resistance is not much in evidence; in the case of black slaves, perhaps this was because slaves coming from West Africa did not often speak the same, or a similar, dialect or language.

However, governments were always fearful that slaves might revolt, and so tried to limit access to dangerous weapons, or other implements that could be used as weapons, such as long staffs or knives, and to stop Africans meeting together in large numbers. So they often passed laws forbidding slaves from carrying weapons, forbidding the congregation of more than a certain number of Africans, forbidding slaves from going to taverns (King Manuel I of Portugal decreed that any innkeeper in Lisbon who sold wine or food to any slave, black or white, would be fined),36 and even in some cases from carrying drums or tambourines, which might have led to a heady loss of control.37 Individual resistance mainly took the form of running away; descriptions of runaway slaves were common, as are letters demanding their return. Only rarely did a slave kill his or her master, but the penalties for a slave who did so were draconian. The tendency to view all black people as slaves occurred in parts of Europe where there were significant numbers of black slaves, and black non-slaves were sometimes required to prove their free status.38

Further important differences related to where and how slaves were sold. Slave markets were not designated physical spaces across much of Renaissance Europe, which could be one reason why there are few, if any, illustrations of slave markets. A French printmaker, Jacques Callot, made an etching of a scene of the ransoming of captives of ca. 1620 (no. 44),39 in a scene where virtually everyone was white, which is not the same as a slave market in Europe where newly captured African slaves are sold on to new owners. Here, instead, white Europeans who have been captured by pirates or overrun in war are ransomed by buyers who take them back to their homes. The setting appears to be a generic Mediterranean scene rather than an actual location. Once again, sub-Saharan Africans were at a disadvantage because of the great distance between Europe and their homelands, so they were not usually ransomed or exchanged. But one enterprising black African of high status who had been captured and taken to Europe promised that if he was returned to Africa, his family would provide ten slaves in his stead, which they duly did.40 Slaves in Italy were usually sold from the agents’ or owners’ homes or premises, and only sometimes on public squares, and the same was probably true in all parts of Europe where there were not many slaves. For instance, in Southampton a black slave was put up for sale in the 1540s by his Italian owner in a square, but no buyer came forward, probably because slavery “did not exist” in England, and the English people in Southampton may not have liked the idea.41 In Lagos in the Algarve, the first place in Europe where black slaves from West Africa were disembarked, memory of the slave market where slaves were sold is still alive hundreds of years later.42 In Lisbon, a great center for arriving slaves, there was in the fifteenth century a Slave House, the Casa dos Escravos, which handled all the financial transactions on behalf of the Crown. Slaves were valued by crown officials and a price tag tied around the slave’s neck.43 Slaves could be viewed at the Slave House or were sold to contractors or brokers, who re-sold slaves at the regular slave auctions in the public square known as the Pelourinho Velho.44 Procedures for sales differed greatly within Europe. At Valencia and at Mantua in Italy, for example, a crucial part of a slave sale was the “interview” between the slave and his or her potential buyer,45 an occurrence that allowed slaves a measure of self-presentation. Some slaves were very successful in refusing to be sold away: they feigned madness, were thoroughly objectionable and out of control, or self-harmed, as in the case of a female slave who put a sewing needle up her nose.46

Treatment of Slaves

When newly enslaved African people arrived in Europe, they had to begin a difficult process of adjustment to becoming a slave. Being renamed was an especially important part of this process, as it signaled a milestone on the long journey of being forced to readjust to a life of new social realities in a new country, and to a new religious allegiance. Many naming practices make tracing Africans in the records complicated. It is difficult to know from fifteenth- and sixteenth-century documentary sources who is an African, unless their place of origin or skin color is spelled out. When Africans were enslaved and taken to Europe, they were given European Christian names and were forced to drop their own names. A few North African Muslims held onto their own names, so, for example, there is a North African slave named Barack in a Genoese document from 1432,47 but sub-Saharan Africans mainly did not. Some sub-Saharan Africans in Africa who were not slaves may have chosen their own Christian names when they converted. The ruler of the Kongo, his close family and his “nobles,” when they accepted Christianity in 1491, were baptized with exactly the same names as their royal and noble counterparts in Portugal: the ruler was called João, after King João II of Portugal, his consort was called Leonor, after Queen Leonor, and their eldest son was called Afonso, after Afonso, the son of João and Leonor.48 And so on with all the nobles. Slaves were given Christian names, often from quite a small pool, so in Italy there are many slaves named Lucia, Giovanni, or Marta, and in Portugal there are hundreds of slaves called Maria, António, Catarina, or Francisco.49 They were often referred to by this Christian name in conjunction with the surname of their owner, which would change once again if they were sold to other owners. Many Africans were given nicknames related to their skin color (Carbone / Charcoal, or Maura / Moor),50 and there were many “joke” names too, such as John White, or its equivalent, which is found across Europe. Occasionally, instead of being given the surname of their owner, they were given their owner’s Christian name, and another “joke” surname was “invented” for them. Edward Winter in England gave his slave the invented surname “Swarthye” so that the slave was known as Edward Swarthye.51 Fashion in slave names went through periods when classical names were common, for example, Pompey or Fortunatus.

Learning a new European language was another vital element of the process of becoming a slave in Europe. Europe was not a linguistic entity, but a conglomeration of countries and areas, many of which had different languages, so often Africans had to learn more than one new European language. Vicente Lusitano was of African descent and wrote a famous book on musical theory. He was born in Portugal, went to Rome in the early sixteenth century, and then went on to a German court, and he must have spoken the languages of all these places.52 The common written language of the educated in Renaissance Europe was Latin, which would have been even more difficult to acquire than a vernacular language. However, there is evidence of Africans not only mastering it,53 but also composing and publishing works in it.54 In terms of spoken communication, creole or pidgin were available to recent African arrivals in Renaissance Europe, although it is not known how extensively they were used. Whether they were or not, in Portugal fala de Guiné (Guinea speak—that is, the type of speech used by West Africans) and its Spanish equivalent habla de negros (black speak) were mocked in contemporary plays, poems, and jokes.55

There was discrimination at all levels, just as there was acceptance at all levels, so the picture remains mixed. The sixteenth-century black Portuguese court jester or fool, João de Sá de Panasco, is a good example of a very talented performer who, while promoted and protected by the Portuguese monarchs, also suffered vicious insults about his former slave status and his black skin from the tongues of nobles and courtiers jealous of his position and success.56 However, he was successful enough to be made a knight of the Order of Santiago, one of only three black Africans to be so honored in the sixteenth century, the other two being prominent black courtiers at African courts.57 More jokes against him survive than jokes that he made himself. These jokes reveal a great deal about reactions or responses to a successful black African living a protected life at court.

Nor should the sometimes punitive nature of European Renaissance slavery be ignored; as was to be expected, this differed from place to place. At its worst, for instance in Valencia, slaves in individual houses were locked up at night in wooden cages and restrained with ropes and stirrups,58 but this was quite exceptional. Slaves could also often be physically punished for misdemeanors more severely than free people, a differentiation that could be enshrined in law. Slave-owners could be tried if a slave died as a result of punishment, but few were—societal pressure militated against too harsh a cruelty more successfully than the law. It is also worth remembering that nearly all groups in the household at this time were liable to physical chastisement by the heads of the household: wives, children, servants, and slaves, so slaves were by no means in a unique position in this respect. Another identifying feature of slaves was that they could be branded: slaves belonging to the Portuguese crown were branded on the arm. All slaves taken to São Tomé from Benin or elsewhere after 1519 were branded with a cross on their upper right arm,59 later changed to a G, the marca de Guiné.60 In Spain, slaves were branded with an S on one cheek, and an I, signifying a clavo, a nail, on the other, so that the whole read esclavo, the word for slave.61 In Italy and elsewhere, slaves were branded only if they ran away, not as a primary means of identification.

The treatment of slaves can be grouped under several headings. First of all, Europe was not a place of one religion. The established religion in mid-fifteenth-century Europe was Catholicism, but there were also small but significant numbers of Jews and of Muslims. By the mid-sixteenth century, there were also large numbers of Protestants, of many different types. The papacy usually approved and backed up the institution of slavery, and priests, bishops, cardinals, and popes all owned slaves. The first cargo of slaves to include black slaves arrived in Europe at Lagos in southern Portugal in 1444, and some of this initial cohort were sent to ecclesiastical establishments. In terms of conversion, black slaves brought from West Africa who were considered “animist,” were often summarily baptized by being sprinkled with water on board ship or, if not, they were supposed to be baptized by their new owners. Often this compulsory baptism was more honored in the breach than in the observance, even at the highest levels of society. King João II of Portugal offered incentives in the form of clothing, called “victory clothes” if his slaves converted, but in 1493, at least three of his slaves still retained their African names, transcribed into Portuguese as Tanba, Tonba, and Baybry,62 which demonstrates that they had not converted to Christianity because they had not been given Christian names. Pope Leo X’s bull Eximiae devotionis of 1513 provided for the erection of a baptismal font in the Church of Nossa Senhora de Conçeição in Lisbon specifically to cater for the baptism of newly arrived black slaves.63 Islamic North Africans, if they converted, sometimes had more elaborate baptismal ceremonies (as did Jews) because Islam and Christianity were locked in conflict and conversion of the “infidel” was highly prized.64 Baptism did not alter slave status. Slaves were afforded differential treatment according to their perceived religion, rather than their skin color. Muslims were regarded less favorably than “animist” black Africans, only a small percentage of whom had been Islamicized; because Muslims were the traditional enemies of Christians in Europe, as slaves they were believed to be more difficult and less trustworthy than non-Muslims.

The European country of destination mattered, as treatment could vary widely. There was a difference in how slaves were perceived and treated between countries with differing political systems: monarchies, republics, courts. Countries also had differing traditions of slavery. In legal terms, slavery was enshrined in Roman law, but various countries and cities in Europe either did not adhere to Roman law or promulgated local statutes that overrode certain aspects of it. Distinctive law codes were composed for societies with large numbers of slaves. For instance, royal laws promulgated in Portugal from 1481 to 1514—a period when many black Africans arrived—were collected into the law code called the Ordenações Manuelinas.

There were special problems in parts of Northern Europe such as Sweden and England, where slavery was not legal because it had been abolished. In 1532, an interesting case arose in the Low Countries. A “white Moor” called Simon, branded with a P on one cheek and an M on the other, who was a slave of the Portuguese ambassador to the emperor Charles V, absconded by returning to the Low Countries while his master continued to Germany. When his return was requested through the usual diplomatic channels, the Grand Conseil, the highest court of law in the Low Countries, refused to help, stating that in their country, personal slavery did not exist.65 Yet in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, African “slaves” continued to be brought into England, Sweden, and the Low Countries by their masters, and were treated in precisely the same manner as they had been when they were living with their “owners” in countries where slavery was legal. To a certain extent, the illegality of slavery in England must have been known, even if only by hearsay, as there is a case of a black African’s refusal to be someone’s slave. In 1587, Hector Nunes, a forcibly converted Portuguese ex-Jew living in London, bought a black male slave from an English sailor for £4 10s. but, as his would-be master put it, the “slave” utterly refused to serve him. When Nunes went to court to try to force his “slave” to acquiesce, he found no satisfaction, instead being told that his only recourse was to apply to a debtors’ court for the repayment of his costs.66 In addition, as slavery was not supposed to exist, slaves could not be freed by clauses in their masters’ wills because the law of England did not recognize them as slaves in the first place. There were also differences in how Africans were viewed and treated that varied according to how many Africans there were in the area or country, and therefore how rare or common they were. In German cities and in Scandinavia, where black Africans were the exception, they stood out.

It is important to notice how issues relating to sex and sexual relations, and to marriage, were dealt with in connection to slaves. Female African slaves—like all other slaves and servants living in a household—were vulnerable to sexual assault from their male masters, but they were also at the mercy of many other men, both in and outside the household. The lies that slave-owners told in this respect are extraordinary; one claimed in a Spanish court of law that it was not lust that had driven him to have sex with his slave, but a desire to find relief from the pain of his kidney stones.67 Most European laws at the time included clauses detailing how much the master of a female slave should be paid if someone made his slave pregnant. But there are also very early cases of black “couples” who managed to have children together in Europe. For example, a black “couple” in Florence in 1470 had a child,68 as did other couples in Venice and Mantua, and there are more examples from Spain and Portugal. In many places, skin color was not at issue, although there was interest in what the skin color of the children born to a mixed black and white couple would be, and there are cautionary tales of white women being discovered to have been unfaithful when they produced black-skinned babies.69 Instead, it was status that was most relevant. According to Roman law, the legal status of the child followed that of the mother, so a child of a slave mother was a slave. But Florentine city statutes, on the contrary, decreed that the status of a child followed that of its father,70 so a child born to a slave mother and a free middle-class father was free in Florence. Noble or middle-class women were not supposed to have affairs with their black servants, although a double standard operated, and the orphanages of Italy contained many babies born to white patrician men and their female slaves or servants, including numbers of part-African ones.71 Many slaves who were freed by their masters or mistresses were married off to white husbands. This flags one of the most important issues of European Renaissance slavery: What happened to the descendants of these black African slaves? The answer is that they have been “swallowed up” by the white population over successive generations. It is only now with DNA testing that some people in Europe are beginning to discover that they had black ancestors. There is no historically black population from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries still in existence, although there is a village in Portugal (São Romão near Alcácer do Sal) and two small towns in Spain (Niebla and Gibraleón, both in the province of Huelva) where African features lingered longer than elsewhere, and where some of the now white inhabitants acknowledge their descent from black African slaves.

Finally, in terms of treatment of slaves, access to education for slaves was not blocked by law, but usually did not happen, as slaves were needed for their work and hiring tutors cost money; however, there are examples of black slaves belonging to teachers or educated people who allowed or encouraged their slaves to gain an education.72 Some of these slaves, often later manumitted, were of part-African descent, and were probably the children of their mothers’ owners, which was an added reason why their fathers would want them to be educated. Most occupations required only minimal formal education (as opposed to training or apprenticeships), and could be done either by slaves or by free/d people, which is indicative of the way in which slavery was conceptualized. Slaves in Europe could be hired out by their owners, and if they worked with their owners at a salaried job, the salary was paid to the owner. An example of this is a black slave who in 1516 served as part of the police watch led by his master in Beira in Portugal; his master was given the slave’s pay.73 Slaves were often taught vital skills by the people who owned them and alongside whom they worked, such as goldsmiths’ work or cooking or fencing, and so were able to earn a living when they were freed. Some slaves, such as musicians or singers or dancers, must have arrived in Europe from Africa already with skills, and there is ample evidence of how these skills were valued and employed in Europe. The North Italian drawing of musicians and a black African singer from the second half of the sixteenth century once again shows white and black people engaged in a joint endeavor (fig. 11), although the African may have learnt to sing in Europe. Some black singers and musicians were employed at courts and were not slaves.74

We know John Blanke, “the black trumpet” at the court of King Henry VII of England, who appears in two different images alongside white colleagues in the Great Tournament Roll of Westminster of 1511, wearing distinctive headgear but in otherwise identical dress (fig. 12),75 was free or freed because he was paid a salary.76 Wherever and however Africans acquired their skills, integration into European life was easier on account of them.

African protagonists and African minor characters—whether real or imagined, genuine likenesses or composite inventions—featured in a number of fifteenth and sixteenth-century European representations, sometimes depicted by the greatest Renaissance artists. The African presence in Renaissance Europe had a visual dimension of an outstanding nature that allows visual, spatial, and conceptual aspects of Renaissance European slavery to be revisited. These representations are interesting in their own right, but if they are used in conjunction with the enormous and greatly varied documentary legacy left by slavery, there is the possibility that the lives of African slaves and those of African descent in Renaissance Europe can be more authoritatively re-created, and the European chapter of the global history of slavery can be better understood.

Endnotes

- See, e.g., Steven A. Epstein, Speaking of Slavery: Color, Ethnicity, and Human Bondage in Italy (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2001), 107–12, for a description of 357 white slaves in late fourteenth-century Florence.

- Kate Lowe, “La place des Africains sub-sahariens dans l’histoire européenne, 1400–1600,” in Dieudonné Gnammankou and Yao Modzinoum, eds., Les Africains et leurs descendents en Europe avant le XXe siècle (Toulouse: MAT Éditions, 2008), 71–82, at 75–80.

- K.J.P. Lowe, “The Stereotyping of Black Africans in Renaissance Europe,” in T.F. Earle and K.J.P. Lowe, eds., Black Africans in Renaissance Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 17–47 at 44–47.

- Giovanna Fiume and Marilena Modica, eds., San Benedetto il moro: Santità, agiografia e primi processi di canonizzazione (Palermo: Città di Palermo, 1998); Giovanna Fiume, “Il processo ‘de cultu’ a Fra’ Benedetto da San Fratello (1734),” in Giovanna Fiume, ed., Il santo patrono e la città: San Benedetto il Moro: culti, devozioni, strategie di età moderna (Venice: Marsilio, 2000), 231–52; and Nelson Minnich, ‘The Catholic Church and the Pastoral Care of Black Africans in Italy,” in Earle and Lowe, eds., Black Africans, 280–300 at 298–99.

- Kate Lowe, “Visible Lives: Black Gondoliers and Other Black Africans in Renaissance Venice,” Renaissance Quarterly [2013].

- Paul H.D. Kaplan, “Italy, 1490–1700,” in The Image of the Black in Western Art, 3: From the “Age of Discovery” to the Age of Abolition, part 1: Artists of the Renaissance and Baroque, ed. David Bindman and Henry Louis Gates, Jr. (Cambridge Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University

Press, 2010), 93–190 at 94–96; and Lowe, “Visible Lives.” - Theodor Hampe, Das Trachtenbuch des Christoph Weiditz: Von seinen Reisen nach Spanien (1529) und den Niederlanden (1531/31) (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1927), pls. xlvii, lxiii, lxiv, lxv, lxvi for slaves wearing anklets. The inscription is on pl. xlvii.

- William G. Thalmann, “Some Ancient Greek Images of Slavery,” in Richard Alston, Edith Hall, and Laura Profitt, eds., Reading Ancient Slavery (London and New York: Bristol Classical Press, 2011), 72–96 at 78–86.

- Moriz Thausing ed., Dürers Briefe, Tagebücher und Reime (Vienna: Wilhelm Braumüller, 1872), 114: “Ich habe mit dem Stift seine Mohrin porträtiert,” after 17 March and before 6 April 1521.

- See below, note 64. Antwerp is in Brabant, and it is not absolutely clear if the Grand Conseil’s jurisdiction included Brabant at this date or if it was exempt. The Grand Conseil took no appeals from Brabant after 1491, and Brabant’s exemption was confirmed in 1530. However, the law relating to slavery is very likely to have been uniform throughout the Low Countries.

- Paul H.D. Kaplan, “Titian’s Laura Dianti and the Origins of the Motif of the Black Page in Portraiture,” Antichità viva 21:1 (1982): 11–18 at 11–12, and 21:4, 10–18 at 13–14; P.H.D. Kaplan, “Isabella d’Este and Black African Women,” in Earle and Lowe, eds., Black Africans, 125–54 at 154; and Kaplan, “Italy, 1490–1700,” 107–10 and fig. 44.

- Annemarie Jordan, “Images of Empire: Slaves in the Lisbon Household and Court of Catherine of Austria,” in Earle and Lowe, eds., Black Africans, 155–80 at 175–79 and fig. 45.

- A. Luzio and R. Renier, “Buffoni, nani e schiavi dei Gonzaga ai tempi d’Isabella d’Este,” Nuova antologia di scienze, lettere ed arti, 3rd series, 34 (1891): 618–50, and 35 (1891): 112–46 at 141; Kate Lowe, “Isabella d’Este and the Acquisition of Black Africans at the Mantuan Court,” in

P. Jackson and G. Rebecchini, eds., Mantova e il Rinascimento italiano: Studi in onore di David S. Chambers (Mantua: Sometti, 2011), 65–76 at 70. - Jorge Fonseca, Escravos e senhores na Lisboa Quinhentista (Lisbon: Colibri, 2010), 88–100.

- Os Negros em Portugal—Secs. XV a XIX, exh. cat., Mosteiro de Belém (Lisbon: Comissão Nacional para as Comemorações dos Descobrimentos Portugueses, 1999), 104–7; Lowe, “The Stereotyping of Black Africans,” 29 and figs. 3, 4, and 9; and the entry by Vitor Serrão in Jay A. Levenson, ed., Encompassing the Globe: Portugal and the World in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. Reference Catalogue (Washington, D.C.: Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, 2007), 21–22.

- Debra Blumenthal, Enemies and Familiars: Slavery and Mastery in Fifteenth-Century Valencia (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2009), 82n8.

- Sergio Tognetti, “The Trade in Black African Slaves in Fifteenth-Century Florence,” in Earle and Lowe, eds., Black Africans, 213–24 at 223–24.

- Jordan, “Images of Empire,” 73.

- John Vogt, “The Lisbon Slave House and African Trade, 1486–1521,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 117:1 (1973): 1–16 at 10.

- Ibid., 11; João Brandão, “Majestade e Grandezas de Lisboa em 1552,” ed. Anselmo Braamcamp Freire and J.J. Gomes de Brito, Archivo Historico Portuguez 11 (1917): 8–241 at 94.

- Blumenthal, Enemies and Familiars, 46–47; and Lowe, “Isabella d’Este,” 70.

- Blumenthal, Enemies and Familiars, 73–76.

- Domenico Gioffré, Il mercato degli schiavi a Genova nel secolo XV (Genoa: Fratelli Bozzi, 1971), unpaginated table of “schiavi mori.”

- Filippo Pigafetta, A Report of the Kingdom of Congo and of the Surrounding Countries, trans. Margarite Hutchinson (London: Frank Cass, 1970), 76.

- Fonseca, Escravos e senhores, 354–57.

- Fonseca, “Black Africans in Portugal during Cleynaerts’s Visit (1533–1538),” in Earle and Lowe, eds., Black Africans, 121; and Giovanni Mantese, Memorie storiche della chiesa vicentina, III, II (Vicenza: Neri Pozzi, 1964), 665n16.

- Information from Miranda Kaufmann.

- Maria Augusta Alves Barbosa, Vicentivs Lvsitanvs: Ein portugiesischer Komponist und Musiktheoretiker des Jahrhunderts (Lisbon: Estado da Cultura, 1977), 2; and Robert Stevenson, “The First Black Published Composer,” Inter-American Music Review 5 (1982): 79–103.

- Fonseca, “Black Africans in Portugal,” 119–20.

- Baltasar Fra Molinero, “Juan Latino and His Racial Difference,” in Earle and Lowe, eds., Black Africans, 326–44.

- Jeremy Lawrance, “Black Africans in Renaissance Spanish Literature,” in Earle and Lowe, eds., Black Africans, 70–93; Ditos Portugueses dignos de memória, ed. José Hermano Saraiva (Lisbon: Europa-América, 1997), 197.

- A.C. de C.M. Saunders, “The Life and Humour of João de Sá de Panasco, o Negro, Former Slave, Court Jester and Gentleman of the Portuguese Royal Household (fl. 1524–1567,” in F.W. Hodcroft et al., eds., Medieval and Renaissance Studies on Spain and Portugal in Honour of P.E. Russell (Oxford, The Society for the Study of Mediaeval Languages and Literature, 1981), 180–91.

- Francis A. Dutra, “A Hard-Fought Struggle for Recognition: Manuel Gonçalves Doria, First Afro-Brazilian to Become a Knight of Santiago,” in Francis A. Dutra, Military Orders in the Early Modern Portuguese World: The Orders of Christ, Santiago and Avis (Aldershot: Variorum, 2006), XII, 91–113 at 93–94; and Lowe, “‘Representing’ Africa,” 114.

- Blumenthal, Enemies and Familiars, 116–17.

- Vogt, “The Lisbon Slave House and African Trade,” 9n50.

- Saunders, A Social History of Black Slaves and Freedmen in Portugal, 13.

- Alessandro Stella, “‘Herrado en el rostro con una S y un clavo’: L’homme-animal dans Espagne des XV–XVIIIe siècles,” in Henri Bresc, ed., Figures de l’esclave au MoyenAge et dans le monde moderne (Paris: L’Harmattan, 1996), 147–63.

- Saunders, A Social History of Black Slaves and Freedmen, 40.

- António Brásio, ed., Monumenta Missionaria Africana: África Ocidental (1471–1531), 6 vols., 1st series (Lisbon: Agência Geral do Ultramar, 1952–88), 1:275–77; and Saunders, A Social History of Black Slaves and Freedmen, 41.

- Wipertus Rudt de Collenberg, “Le baptême des Musulmans esclaves à Rome aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles,” Mélanges de l’École française de Rome: Italie et Méditerranée, 101:1(1989): 9–181 at 76–117, for the names of godparents present at these ceremonies in Rome between 1614 and 1650; they included cardinals, countesses, and princesses.

- Robert van Answaarden, Les Portugais devant le Grand Conseil des Pays-Bays (1460–1580) (Paris: Fondation Calouste Gulbenkian, 1991), 250–53.

- Roslyn L. Knutson, “A Caliban in St. Mildred Poultry,” in Tetsuo Kishi, Roger Pringle, and Stanley Wells, eds., Shakespeare and Cultural Traditions (Newark: University of Delaware Press/London and Toronto: Associated University Presses, 1994), 110–26 at 116.

- Blumenthal, Enemies and Familiars, 179.

- Kate Lowe, “Black Africans’ Religious and Cultural Assimilation to, or Appropriation of, Catholicism in Italy, 1470–1520,” Renaissance and Reformation/Renaissance et réforme, 31:2 (2008): 67–86 at 70–73.

- Cf. Megan Holmes, “‘How a Woman with a Strong Devotion to The Virgin Mary Gave Birth to a Very Black Child’: Imagining ‘Blackness’ in Renaissance Florence,” in Peter Bell, Dirk Suckow, and Gerhard Wolf, eds., Fremde in der Stadt: Ordnungen, Repräsentationen und soziale Praktiken (13.–15. Jahrhundert) (Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2010), 333–51, 447–48, 517–24 at 333–34, 336.

- Kate Lowe, “Black Africans’ Religious and Cultural Assimilation,” 73.

- On Florence, see Richard C. Trexler, “The Foundlings of Florence, 1395–1455,” History of Childhood Quarterly, 1:1 (1973): 259–84; Philip Gavitt, Charity and Children in Renaissance Florence: The Ospedale degli Innocenti, 1410–1536 (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1990).

- Fra Molinero, “Juan Latino,” 329.

- Saunders, A Social History of Black Slaves and Freedmen, 131.

- Tess Knighton, Música y músicos en la corte de Fernando el Católico, 1474–1516 (Zaragoza: Institución Fernando el Católico, Sección de Musica Antigua, 2001): 197–205.

- Sydney Anglo, ed., The Great Tournament Roll of Westminster: A Collotype Reproduction of the Manuscript, 2 vols. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1968), 2: plate 3, membranes 3–5, and plate xviii, membranes 28–29.

- Sydney Anglo, “The Court Festivals of Henry VIII: A Study Based upon the Account Books of John Heron, Treasurer of the Chamber,” Bulletin of the John Rylands Library 43 (1960): 12–45 at 42, and Lowe, “The Stereotyping of Black Africans,” 39 and fig. 8.

Chapter excerpt from Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe (2012, 13-33), edited by Joaneath Spicer, Walters Art Museum, republished under fair use for educational, non-commercial purposes.