The history of the saeculum obscurum exposes a recurring vulnerability in human institutions. Corruption does not destroy authority simply by existing.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: When Corruption Becomes a Loyalty Test

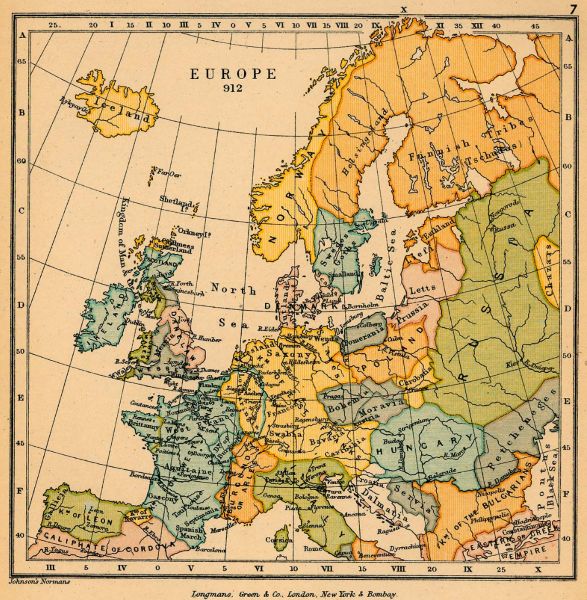

The tenth-century papacy occupies an uneasy and unusually well-documented place in medieval history, not because later moralists projected scandal backward, but because contemporaries themselves recorded a prolonged collapse of credibility at the center of Western Christendom. The period often labeled the saeculum obscurum unfolded amid political fragmentation, aristocratic domination of Rome, and the absence of effective external restraint on papal behavior. What distinguishes it from other moments of clerical scandal is the sheer openness with which accusations circulated. Allegations of sexual exploitation, violence, sacrilege, and criminal conduct were not whispered rumors confined to hostile pamphlets or distant observers. They were recorded in annals, correspondence, and reformist commentary by writers who understood themselves to be documenting a crisis, not inventing one. The papacy continued to function liturgically and politically even as its moral authority visibly eroded, forcing contemporaries to confront a destabilizing question. How much corruption could an institution absorb before belief itself became untenable.

What follows approaches the so-called papal “pornocracy” not as an episode of personal vice or sensational depravity, but as a structural moment in the history of institutional survival. Chroniclers such as Liudprand of Cremona and Flodoard of Reims did not write from the margins of power. They were diplomats, clerics, and embedded political actors whose works circulated among courts and episcopal elites. Their accounts display neither hesitation nor surprise in recounting papal misconduct, suggesting that such behavior had become normalized within elite discourse even as it remained morally shocking. Crucially, these writers framed corruption as a political and spiritual problem rather than an individual failing. Yet as accusations accumulated, defenders of the papacy increasingly redirected attention away from acts themselves and toward the intentions and affiliations of those making the claims. Moral evaluation was displaced by procedural argument. The question was no longer whether corruption existed, but whether acknowledging it would do greater damage than denial.

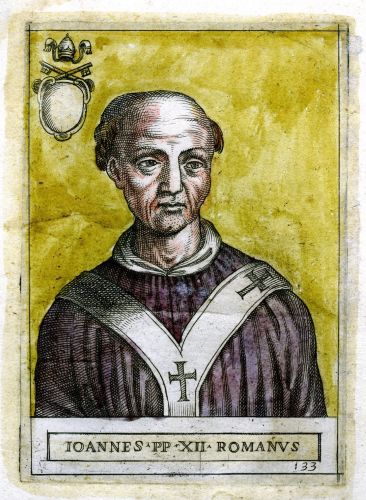

At the center of this dynamic stands Pope John XII, whose reign crystallized the limits of plausible denial. Formally accused in 963 of crimes ranging from sexual violence to sacrilege, John was condemned not by hostile outsiders but by an imperial synod convened in Rome itself. The proceedings, preserved in multiple sources, make clear that no one present argued that the papal office had become morally compromised by ignorance or accident. The defense rested on authority, not innocence. To admit wrongdoing was framed as an attack on the Church, while disbelief became a demonstration of loyalty. The papacy survived not by refuting evidence, but by redefining what evidence could mean.

The pattern established in tenth-century Rome has proved remarkably durable. When political or religious identity becomes inseparable from institutional power, moral judgment turns inward and dangerous. Truth becomes negotiable, evidence becomes partisan, and disbelief becomes a virtue. The bridge to the modern world is neither strained nor symbolic. It is structural. The mechanisms that allowed medieval believers to defend the papacy against its own chroniclers are the same mechanisms that allow contemporary political movements to dismiss overwhelming documentation as conspiracy or malice. Once loyalty replaces judgment, corruption ceases to be a scandal and becomes a test.

Rome without Restraint: The Political Ecology of Tenth-Century Papal Power

The collapse of effective imperial oversight in Italy during the late ninth and early tenth centuries transformed the papacy from a transregional religious authority into a locally captured institution. After the disintegration of Carolingian power, Rome lacked a durable administrative or military framework capable of regulating papal elections or disciplining papal conduct. Sacred authority remained intact in theory, but enforcement depended almost entirely on unstable local politics. This imbalance left the papacy symbolically exalted yet practically exposed.

Roman aristocratic families quickly moved to occupy this vacuum, treating the papacy as a prize within an intensely competitive political landscape. Lineages such as the Theophylacti embedded themselves deeply in ecclesiastical power through marriage alliances, hereditary patronage, and the strategic use of intimidation. Papal elections became predictable expressions of factional dominance rather than moments of collective discernment or reform. Control of the papacy conferred legitimacy, access to land and revenue, and leverage over rival families, making the office indispensable regardless of its occupant’s moral standing. Repeated manipulation of succession dulled resistance. What initially appeared as corruption hardened into custom, and the sacred character of the office became a resource to be exploited rather than a standard to be upheld.

Within this environment, mechanisms of restraint existed largely on paper. Canon law articulated ideals of clerical behavior, but enforcement depended on elites whose power depended on papal compliance and disorder. Councils and synods possessed theoretical authority to discipline popes, yet they convened only when politically expedient, often under external pressure. Moral language was instrumentalized, deployed selectively in factional struggles rather than applied consistently. Popes learned quickly that consequences followed political miscalculation, not ethical failure. The relevant question was not whether misconduct violated norms, but whether it threatened alliances or destabilized the local balance of power. This recalibration of risk transformed corruption from a liability into a manageable condition of office.

The sacramental function of the papacy further complicated this political ecology. Regardless of personal conduct, popes continued to ordain clergy, consecrate bishops, and perform rites believed essential to Christian order. This created a structural dissonance between moral evaluation and institutional necessity. To question the legitimacy of the office too directly risked destabilizing the religious life of the community itself. As a result, criticism tended to target individuals while preserving the abstract sanctity of the institution. This distinction allowed corruption to be acknowledged rhetorically while neutralized practically.

External powers, particularly the Ottonian emperors, occasionally intervened in Roman affairs, but such interventions were intermittent and transactional. Imperial involvement did not impose consistent moral reform. It substituted one political calculus for another. When emperors intervened, they did so to stabilize authority, not to purify it. Their willingness to tolerate compromised popes so long as order was maintained reinforced the lesson that legitimacy flowed from power alignment rather than ethical standing. Moral failure became secondary to political usefulness.

By the early tenth century, Rome functioned as a system without effective restraint, not because norms were absent, but because incentives discouraged their enforcement. The papacy remained symbolically sacred while practically unguarded, creating a durable contradiction at the heart of ecclesiastical authority. This contradiction shaped elite behavior and public expectation alike. It encouraged conduct that contemporaries recognized as corrupt while simultaneously teaching believers that corruption could be endured without theological collapse. Survival depended not on reform but on adaptation. Scandal no longer threatened legitimacy; it tested the community’s willingness to reinterpret what it already knew. The political ecology of Rome did not fracture under exposure. It stabilized around denial, accommodation, and the disciplined management of obvious wrongdoing.

The Saeculum Obscurum: What Contemporaries Actually Alleged

Accounts of the saeculum obscurum derive not from hostile hindsight or later reformist mythology, but from contemporaries who understood themselves to be recording political reality as it unfolded. Chroniclers writing in the late ninth and tenth centuries did not frame papal misconduct as rumor, hearsay, or private vice exaggerated by distance. They described it as public knowledge with institutional consequences, embedded in the ordinary functioning of Roman power. These writers were often politically connected, ecclesiastically trained, and acutely aware of the gravity of what they were recording. Their decision to write at all suggests not sensationalism but obligation. Silence, in their view, would have been a distortion of the historical record. The resulting accounts vary in tone and emphasis, but they converge in substance, revealing a shared recognition that corruption at the papal center was neither exceptional nor hidden.

Liudprand of Cremona remains the most frequently cited source for this period, but his testimony gains weight when read alongside other contemporary voices rather than treated as a singular polemic. His descriptions of papal behavior, including sexual violence, sacrilege, and the use of ecclesiastical space for criminal activity, are vivid and uncompromising. Yet Liudprand did not present these allegations as shocking revelations intended to persuade skeptics. He wrote with the assumption that his audience already grasped the outlines of the crisis. His outrage was moral rather than evidentiary. He did not labor to prove that corruption existed; he assumed recognition and demanded judgment for what continued to be tolerated.

Flodoard of Reims offers a complementary perspective, one less accusatory but no less revealing. His annals register papal scandals with a restrained, almost bureaucratic tone that suggests normalization rather than disbelief. Accusations appear alongside military campaigns, episcopal appointments, and diplomatic events without rhetorical escalation. This stylistic restraint is historically significant. It indicates that contemporaries did not experience papal corruption as a disruptive anomaly requiring justification. Instead, it had become part of the expected narrative of Roman affairs, recorded with the same documentary sobriety as any other political development.

What emerges from these sources is not a discrete catalogue of crimes confined to a handful of notorious pontiffs, but a repeating pattern of allegation that spans multiple reigns. Charges of sexual exploitation, violence, simony, and sacrilege recur with such frequency that individual cases blur into a broader structural indictment. Importantly, these accusations were rarely framed as purely moral failures. They described abuses of authority that intersected directly with governance, coercion, and the manipulation of sacred power. Papal authority appears in these accounts not as merely indulgent or dissolute, but as predatory, reinforcing the sense that corruption was embedded in the operation of office rather than incidental to it.

Equally revealing is how these allegations were received and managed. They circulated widely, were acknowledged by elites, and yet failed to produce sustained institutional reckoning. Accusers were challenged not primarily on factual grounds, but on political alignment, social position, and presumed motive. Foreign origin, imperial association, or reformist intent were invoked to discredit testimony without addressing its substance. This response pattern constitutes historical evidence in its own right. It demonstrates that contemporaries regarded the allegations as credible enough to require containment rather than outright dismissal. The saeculum obscurum was not defined by ignorance of corruption, but by the collective development of strategies for living with what everyone knew and few were willing to confront openly.

Pope John XII and the Limits of Plausible Denial

The pontificate of John XII occupies a central place in any serious analysis of the saeculum obscurum because it exposes the point at which denial ceased to be credible even by the standards of the age. Elected pope in 955 while still a teenager, John inherited not only the office but the political entanglements that governed it. Contemporary sources describe a reign characterized by violence, sexual exploitation, and the routine misuse of ecclesiastical space for personal and factional ends. What distinguishes John XII from earlier or later figures is not merely the severity of the allegations, but the degree to which they were publicly articulated and formally adjudicated. His pontificate transformed scandal from background noise into a constitutional problem.

The crisis culminated in 963, when Emperor Otto I convened a synod in Rome that formally accused John XII of a range of crimes, including perjury, simony, sexual violence, and sacrilege. The proceedings, preserved in multiple contemporary accounts, are remarkable not for their lurid detail but for their procedural seriousness. Witnesses testified, charges were enumerated, and the issue was framed as one of governance rather than gossip. Notably, defenders of John did not attempt a comprehensive rebuttal of the allegations. Instead, they challenged the legitimacy of the synod itself, arguing that no authority could judge a reigning pope. The defense shifted the debate from conduct to jurisdiction, effectively conceding the factual terrain while contesting the right to rule on it.

John’s response to the synod further reveals the limits of plausible denial. Rather than appearing to contest the charges, he fled Rome and relied on loyal Roman factions to restore him by force. When he briefly regained control, he exercised authority through retaliation rather than reconciliation. His actions suggested an understanding of power as immunity, not accountability, and reinforced the perception that judgment itself was intolerable.

The aftermath of John XII’s death underscores the institutional lesson drawn from his reign. The papacy survived not by reckoning with the implications of the synod, but by absorbing the episode into a narrative of political disorder rather than moral failure. Subsequent defenders framed the events of 963 as an imperial overreach or a foreign intrusion into Roman autonomy. The question of John’s conduct faded behind arguments about procedure and sovereignty. In this reframing, denial did not require asserting innocence. It required only that belief be redirected away from evidence and toward institutional loyalty. John XII marks the point at which the papacy demonstrated that it could withstand not merely scandal, but the exposure of scandal, so long as allegiance remained intact.

Defending the Office by Discrediting the Evidence

The response to the scandals of the saeculum obscurum reveals a crucial shift in how institutional authority protected itself under pressure. Faced with allegations too specific and too widely circulated to be plausibly denied, defenders of the papacy increasingly abandoned attempts to rebut claims on their merits. Instead, they attacked the credibility of those making them. This strategy did not require disproving accusations. It required reframing them as illegitimate, motivated, or jurisdictionally improper. In doing so, defenders insulated the office from scrutiny while allowing the facts themselves to remain largely unchallenged.

One of the most effective tools in this defensive repertoire was the systematic politicization of motive. Chroniclers and reform-minded critics were portrayed as agents of foreign powers, particularly imperial interests alleged to be hostile to Roman autonomy. Accusations originating beyond Rome were dismissed as the product of ignorance, cultural misunderstanding, or deliberate misrepresentation by outsiders unfamiliar with local realities. Even Roman critics were rarely treated as neutral observers. They were framed as factional operatives using moral language as a weapon in aristocratic power struggles. This reframing allowed defenders to acknowledge the existence of allegations without conceding their legitimacy. The truth of the claims became secondary to the presumed impurity of those advancing them, shifting the moral burden away from the accused and onto the accuser.

Equally important was the appeal to procedural exceptionalism. The claim that no authority could judge a reigning pope became a powerful shield, regardless of the nature of the charges. This argument did not assert papal innocence. It asserted papal inviolability. Moral evaluation was subordinated to institutional hierarchy, and legality replaced ethics as the terrain of debate. The question became not whether corruption existed, but whether acknowledging it would violate the sacred structure of authority itself. In this framework, evidence lost its force not because it was false, but because it was deemed irrelevant.

These strategies proved remarkably effective because they offered believers a psychologically and socially sustainable way to preserve institutional loyalty without confronting moral dissonance. Discrediting evidence allowed supporters to maintain attachment to the papal office while avoiding the destabilizing implications of acknowledgment. Repetition hardened this response into reflex. Skepticism toward accusations became a marker of fidelity, while concern for conduct was recast as subversive or disloyal. Belief no longer required moral clarity, only disciplined suspicion of critique. The defense of the papacy evolved into a culture of managed disbelief, one that prioritized institutional survival over ethical reckoning and trained its adherents to look past what was already known in order to remain aligned with power.

Loyalty over Judgment: How Believers Were Trained to Look Away

The effectiveness of institutional defense during the saeculum obscurum depended not only on elite maneuvering or doctrinal argument, but on the gradual reshaping of belief at every level of religious life. Ordinary clergy and lay believers were not asked to affirm innocence in the face of scandal, nor were they typically presented with formal rebuttals to the accusations circulating around them. Instead, they were trained to suspend judgment altogether. This distinction was crucial. By redirecting attention away from moral evaluation and toward obedience, the Church cultivated a posture in which ethical discernment itself became suspect. Questioning the conduct of the papacy was subtly reframed as a threat to unity, stability, and salvation. In this logic, the greater danger was not corruption, but fracture.

This training occurred less through explicit teaching than through repetition, example, and institutional survival. Scandal followed scandal, accusation followed accusation, and yet the Church endured. Each episode that failed to produce collapse reinforced the lesson that moral outrage was unnecessary and, more importantly, ineffective. Clergy who aligned themselves with institutional authority advanced within the system. Those who pressed ethical concerns found themselves isolated, sidelined, or dismissed as naïve. Believers absorbed a practical wisdom about which questions preserved stability and which invited danger. Loyalty became a lived habit rather than a conscious choice.

The theological framework of the period further deepened this transformation. Emphasis on the sacramental efficacy of office, independent of the personal holiness of the officeholder, allowed believers to compartmentalize belief and behavior with increasing ease. A corrupt pope could still validly ordain priests, consecrate bishops, and preside over rites essential to Christian life. Grace flowed despite sin. What began as a doctrine designed to protect the faithful from uncertainty gradually became a mechanism for moral deferral. If salvation did not depend on the character of the pope, then judgment of that character could be postponed, softened, or abandoned altogether. Ethical discomfort was not resolved. It was absorbed into a theology of endurance.

Social pressure reinforced this logic at the communal level. In tightly knit societies where religious identity structured daily rhythms, public dissent carried real costs. To insist on confronting corruption risked being labeled divisive, arrogant, or spiritually dangerous. Silence, by contrast, signaled humility, trust, and submission to divine order. These signals hardened into expectation. Believers learned that looking away preserved belonging, while insistence on moral clarity threatened it. The refusal to judge was reframed not as fear or complicity, but as faithfulness. Moral restraint became indistinguishable from moral abdication.

The result was not ignorance, but habituation. Believers did not fail to see corruption. They learned to live alongside it without allowing it to disrupt their sense of belonging or identity. This habituation represents one of the most enduring legacies of the saeculum obscurum. It demonstrates how institutions need not persuade followers that wrongdoing is false. They need only teach them that acknowledgment is unnecessary. In such systems, loyalty does not require belief in goodness. It requires only the disciplined management of doubt.

Reform without Reckoning: Why the System Survived

Efforts to reform the papacy in the aftermath of the saeculum obscurum rarely confronted the underlying moral failures that had made reform necessary. Instead, reform movements focused on procedure, discipline, and structure, treating corruption as a technical malfunction rather than a crisis of judgment. The emphasis fell on regulating elections, limiting aristocratic interference, and clarifying jurisdiction. These measures addressed symptoms without interrogating causes. By restoring order without demanding collective moral reckoning, reformers preserved institutional continuity while leaving the deeper logic of denial intact.

This approach reflected both political necessity and psychological caution. A full reckoning with papal corruption would have required acknowledging that the Church had endured, and in many respects functioned, while knowingly led by men accused of grave wrongdoing. Such an admission threatened not only individual pontiffs but the credibility of ecclesiastical authority itself, including the trust believers placed in sacramental life administered under compromised leadership. Reformers walked a narrow and deliberate path. They condemned disorder without naming complicity. They criticized excess without interrogating loyalty. By framing reform as restoration rather than repentance, they offered a way forward that minimized disruption. Believers could accept structural change without confronting the unsettling implications of what had already been normalized and excused.

The language of reform further insulated the institution from accountability. Calls for renewal emphasized purity, order, and proper governance, but rarely addressed the moral costs of prolonged denial. Corruption was treated as an aberration produced by weak structures, not as a predictable outcome of unchecked power. This framing preserved the idea that the institution remained fundamentally sound, even when its leaders were not. In effect, reform became a way of closing the chapter without reading it too closely. The past was acknowledged only insofar as it could be safely bracketed.

The survival of the papacy through reform without reckoning reveals a central paradox of institutional resilience. Systems do not require moral innocence to endure. They require mechanisms that allow communities to reestablish stability without confronting their own thresholds of tolerance. By prioritizing continuity over confession, the Church emerged from the saeculum obscurum outwardly stabilized but inwardly unchanged in its deepest habits of self-protection. The structures were adjusted, elections were regularized, and order was restored, yet the lesson remained intact. Institutions could survive obvious corruption so long as they avoided asking what that survival had required of those who believed, obeyed, and chose to look away.

The Modern Parallel: When Power Redefines Truth

The dynamics that sustained the papacy during the saeculum obscurum did not disappear with medieval Rome. They migrated. When institutions bind identity tightly to power, the mechanisms that once protected sacred authority reappear in secular form. Modern political systems differ in structure and language, but they rely on the same psychological and social accommodations. The problem is not corruption alone. It is the redefinition of truth under conditions where acknowledging reality threatens belonging. In such environments, evidence does not fail. It is rendered optional.

Contemporary political movements increasingly mirror the medieval pattern in their treatment of scandal. Allegations of misconduct are not evaluated on evidentiary grounds but filtered through loyalty. The question asked is not whether claims are credible, but whether they originate from allies or enemies. As in tenth-century Rome, accusation itself becomes suspect. Critics are framed as partisan operatives, hostile elites, or foreign agents. The effect is to shift attention away from the substance of claims and toward the presumed illegitimacy of those who raise them. Truth becomes positional rather than factual.

The modern American case provides an especially stark illustration of this process. Under President Donald Trump’s return to office in 2025, documented misconduct, criminal convictions, and repeated violations of democratic norms have not produced collective moral reckoning. Instead, they have been absorbed into a narrative framework designed to neutralize their meaning. Supporters rarely deny that troubling behavior occurred. They acknowledge it selectively, then reclassify it as exaggerated, provoked, or insignificant when weighed against perceived threats from political opponents. Courts, journalists, prosecutors, and civil servants are portrayed not as neutral arbiters but as corrupted institutions acting in concert. Loyalty to Trump is reframed as loyalty to the nation itself, and skepticism toward evidence becomes a badge of civic virtue. This mirrors the medieval defense of the papacy, where protecting the office required treating accusers as enemies of order rather than participants in moral accountability.

Media ecosystems now play the role once occupied by aristocratic factions and clerical networks. Information circulates widely and rapidly, but interpretation is tightly managed within partisan communities. Evidence is not hidden from view. It is reframed, contextualized, and repeatedly neutralized through narrative saturation. Contradictory facts are explained away as manipulation or provocation, while repetition dulls their impact. Scandal fatigue sets in. Each controversy that fails to produce consequence reinforces the lesson that outrage is unnecessary. As in the saeculum obscurum, the endurance of the leader or movement teaches followers that accountability is neither forthcoming nor required, and that disbelief is the most adaptive response.

What makes this parallel particularly dangerous is the erosion of shared standards for judgment. In medieval Rome, the sacred character of the papacy provided a theological rationale for suspending evaluation. In the modern context, identity politics and grievance narratives perform a similar function. Political allegiance becomes existential, bound to culture, identity, and perceived survival. To acknowledge corruption is no longer a moral act. It is a betrayal. Belief systems evolve accordingly, filtering facts based on their social consequences rather than their veracity. Truth becomes subordinate to cohesion, and denial becomes a form of belonging.

The continuity between medieval and modern cases lies not in personalities, but in structure. Institutions under threat do not primarily survive by persuasion or secrecy. They survive by training followers to reinterpret reality in ways that preserve loyalty. The saeculum obscurum demonstrates that corruption does not need to be concealed to be endured. It needs only to be normalized and managed. When power succeeds in redefining truth as loyalty, scandal loses its capacity to disrupt. What remains is not ignorance, but a disciplined refusal to judge.

“Everyone Knows”: Shared Knowledge and Collective Denial

One of the most revealing features of both the saeculum obscurum and its modern parallels is the presence of shared knowledge that fails to produce shared judgment. Corruption in tenth-century Rome was not hidden from elites or entirely unknown to the broader Christian world. Chroniclers wrote openly. Synods recorded accusations. Political actors behaved as though the allegations were credible. And yet this knowledge circulated without catalyzing decisive institutional response. What mattered was not whether information was available, but how communities were trained to live with it. Knowledge existed, but it was socially neutralized.

This phenomenon depended on a subtle but powerful division between private recognition and public speech. Individuals could acknowledge corruption in conversation, correspondence, or even historical writing while carefully avoiding its implications in collective decision-making. The boundary between knowing and acting was not intellectual but social. To move from awareness to accountability required crossing a threshold that carried real risk. Speaking openly in ways that demanded consequence threatened reputation, safety, and belonging. Silence, by contrast, preserved standing and relationships. This dynamic disciplined behavior. People learned how to know without acting, how to recognize wrongdoing while signaling restraint, and how to participate in a shared fiction that allowed the community to continue without rupture.

Collective denial does not require unanimity or coercion. It requires only enough shared restraint to prevent knowledge from becoming consequential. In medieval Rome, this restraint was reinforced by hierarchy, theology, and fear of disorder. In modern political systems, it is reinforced by media ecosystems, partisan identity, and social sanction. In both cases, denial operates less as a rejection of facts than as an agreement about what must not be acted upon. Everyone knows, but everyone also knows what it would cost to say so publicly in a way that matters.

The endurance of such systems reveals a sobering truth about institutional failure. Exposure alone does not dismantle power, and documentation does not compel accountability. When communities are organized around loyalty rather than judgment, knowledge becomes something to be managed rather than confronted. This management produces moral numbness. The phrase “everyone knows” signals not a prelude to reform, but the stabilization of denial. It marks the point at which truth remains visible yet politically irrelevant, absorbed into the background of collective life without ever being allowed to challenge authority or alter outcomes.

Conclusion: When Truth Becomes Optional

The history of the saeculum obscurum exposes a recurring vulnerability in human institutions. Corruption does not destroy authority simply by existing, even when it is obvious, documented, and widely acknowledged. What determines survival is not innocence but the capacity to redirect judgment. Tenth-century Rome demonstrates that institutions endure by teaching their followers how to live with what they know without allowing that knowledge to become decisive. The papacy did not survive because its leaders were believed to be virtuous. It survived because belief was reorganized around loyalty rather than moral evaluation.

This reorganization followed a consistent logic. Evidence was not erased. It was reframed. Accusations were not silenced. They were discredited by association. Judgment was not forbidden outright. It was rendered socially dangerous. Believers learned that stability depended on restraint, not truth-telling. The result was a culture in which corruption could be acknowledged privately while denied any public consequence. This pattern did not require universal agreement. It required only enough shared compliance to keep knowledge inert.

The modern relevance of this history lies in its structure, not its setting. Contemporary political systems reproduce the same dynamics whenever identity becomes fused with power and belonging depends on disbelief. When leaders or movements persuade followers that acknowledging wrongdoing threatens the community itself, truth loses its moral authority. It becomes something to be weighed against loyalty, convenience, or fear. In such conditions, denial is not ignorance. It is participation. Institutions survive not by convincing people that corruption is unreal, but by convincing them that confronting it is unnecessary or disloyal.

The lesson of the saeculum obscurum is neither medieval nor distant. It is a warning about how easily truth becomes optional when power teaches people how to look away together. Exposure does not guarantee accountability. Documentation does not ensure reform. Only communities willing to privilege judgment over loyalty can prevent corruption from becoming normalized. When they do not, institutions may endure, but at the cost of transforming belief itself. What remains is authority without credibility, survival without integrity, and a truth that everyone knows but no one is allowed to use.

Bibliography

- Arnold, Jack L. “The Height and Decline of the Papacy (1073—1517)

- Medieval Church History, part 3.” IIIM Magazine Online 33:1 (1999).

- Brown, Peter. The Rise of Western Christendom. 2nd ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2003.

- Duffy, Eamon. Saints and Sinners: A History of the Popes. 4th ed. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997.

- Flodoard of Reims. Annals. Translated by Steven Fanning and Bernard Bachrach. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011.

- Hurley, Natasha. “Pornocracy’s Queer Circulations.” Cultural Critique 100 (2018): 157-175.

- Levitsky, Steven, and Daniel Ziblatt. How Democracies Die. New York: Crown, 2018.

- Liudprand of Cremona. The Complete Works of Liudprand of Cremona. Translated by Paolo Squatriti. Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2007.

- Mann, Horace K. The Lives of the Popes in the Early Middle Ages, Vol. IV. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner, 1910.

- Partner, Peter. The Lands of St. Peter: The Papal State in the Middle Ages and the Early Renaissance. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1972.

- Richards, Jeffrey. The Popes and the Papacy in the Early Middle Ages, 476–752. London: Routledge, 1979.

- Stanley, Jason. How Fascism Works: The Politics of Us and Them. New York: Random House, 2018.

- Szromek, Adam R. “The Papacy as Intangible Cultural Heritage.” Heritage 8:8 (2025): 323.

- Wickham, Chris. The Inheritance of Rome: Illuminating the Dark Ages, 400–1000. New York: Penguin, 2009.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.04.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.