Vincent Gigante’s story closes not with the triumph of a mythic criminal, but with the quiet unraveling of a man who had turned deception into an institution.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

On a chilly autumn morning in Greenwich Village, a figure emerged from a narrow brownstone, dressed in a faded bathrobe and pajama bottoms, clutching a thin metal coffee cup. He shuffled across the sidewalk, his hair unkempt, muttering low and indistinct words as curious pedestrians stepped aside. A beat-up sedan idled nearby and a discreet passenger slipped out, exchanged a quick word and withdrew. Behind the quotidian scene, however, the man in the robe was more than a rambling eccentric: he was pulling strings millions of dollars deep, his power seated in silence as much as shadow. That man was commonly known as “Chin.”

Vincent “Chin” Gigante had for decades occupied the summit of one of New York’s most powerful crime families while simultaneously cultivating a public persona of mental collapse and confusion. The bathrobe wanderings were real appearances, but the performance was as finely tuned as any boxing match in his youth. His seeming infirmity provided a cloak, a buffer against prosecution while his underlings maintained the day-to-day operations. The contrast between the spectacle and the structure underscores a remarkable inversion of mob governance: a boss hidden in plain sight, delegating via front men, conducting business while feigning incapacity, challenging the means by which law-enforcement locates and prosecutes power.

In what follows I explore how Gigante’s strategic deception (his feigned psychological dysfunction, the use of front bosses, and the delegation of operational control) enabled him to maintain de facto leadership of the Genovese crime family for years. Rather than simply charting the chronology of his rise and fall, I examine how his methods reshaped the architecture of organized-crime leadership and complicated the legal frameworks built to contain it.

Background: Gigante’s Early Life and Entry into the Mob

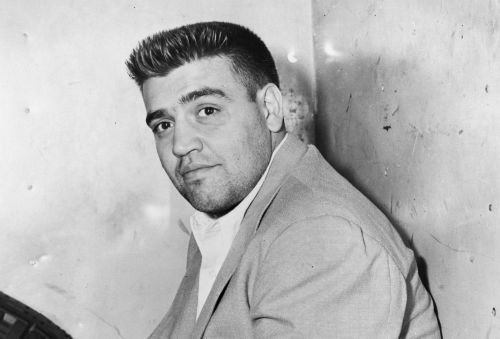

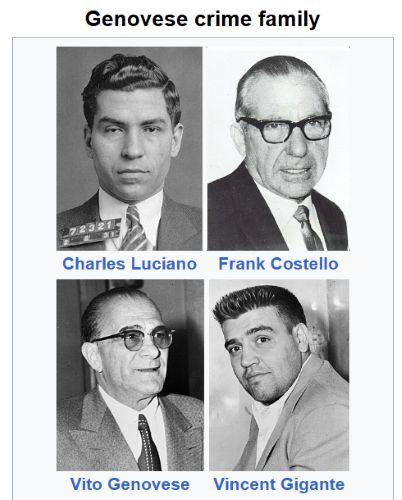

Vincent Louis Gigante was born on March 29, 1928, on the Lower East Side of Manhattan to Salvatore and Yolanda Gigante, Italian immigrants from Naples.1 The family lived modestly; his father worked as a watchmaker, his mother as a seamstress. Gigante grew up among five brothers in a neighborhood where boxing gyms and street corners often offered the same lessons in discipline and survival. As a teenager, he developed a reputation as a capable lightweight boxer, compiling more than two dozen professional bouts between 1944 and 1947 under the nickname “The Chin,” a shortened form of his mother’s affectionate “Cinzino.”2 His brief boxing career, while unremarkable in the ring, introduced him to the men who would define his life outside it: soldiers and associates of the Genovese crime family.

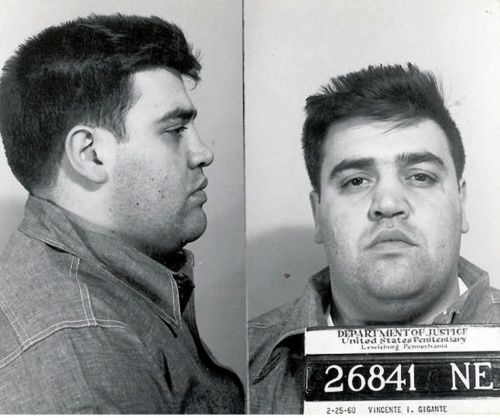

By his early twenties, Gigante had traded gloves for guns.3 Under the mentorship of Vito Genovese, one of the Five Families’ most feared bosses, he became a trusted enforcer. In 1957, Gigante gained underworld notoriety after the attempted assassination of Frank Costello, then the Genovese family boss.4 Costello survived the gunshot to his head and later identified Gigante as the assailant, though he refused to testify, uttering only, “I don’t recognize him.”5 The failed hit nonetheless signaled Gigante’s emergence as a serious player. His loyalty to Genovese and willingness to use violence elevated him within the organization’s hierarchy.

During the 1960s and 1970s, Gigante quietly ascended through the ranks of the Genovese family, managing gambling, loansharking, and construction rackets in New York and New Jersey.6 He became a caporegime, or captain, responsible for supervising his own crew and collecting tribute for the upper echelon. Law-enforcement surveillance later revealed that his influence extended beyond his formal title: even before he officially became boss, Gigante exercised de facto control over family affairs through his relationships with other high-ranking figures.7 The groundwork for his eventual strategy, concealing his power behind proxies, was already being laid.

Ascension to Power and Structuring of the Genovese Family

By the late 1970s, Gigante’s quiet authority within the Genovese organization had become an open secret in underworld circles. Although nominal leadership appeared to rest with figures such as Philip “Benny Squint” Lombardo, real power increasingly flowed through Gigante’s hands.8 Law-enforcement officials had long suspected that the Genovese family, known for its secrecy and discipline, often masked its hierarchy behind deliberate confusion.9 When Lombardo began retreating from day-to-day oversight due to age and illness, Gigante emerged as the natural successor. Yet rather than publicly assuming the title of boss, he opted for concealment, a decision that would become his defining hallmark.

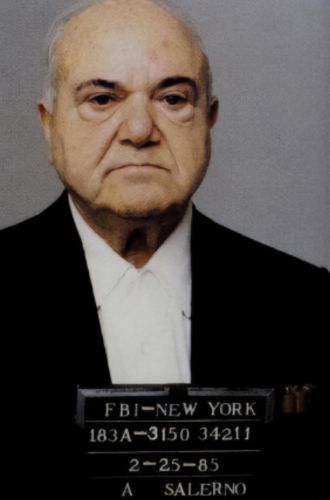

Gigante’s system of “front bosses” was both brilliant and self-protective. He appointed Anthony “Fat Tony” Salerno, a long-trusted caporegime, to serve as the apparent head of the family in the early 1980s.10 To outsiders, including the FBI and federal prosecutors, Salerno appeared to be the Genovese boss, orchestrating its racketeering and union operations from the Palma Boys Social Club in East Harlem.11 In reality, Salerno was the public decoy, tasked with absorbing attention and heat while Gigante directed decisions from his Greenwich Village headquarters, often referred to as “the Triangle.”12 The ruse was so effective that Salerno was convicted in the 1986 Mafia Commission Trial as the Genovese family’s boss, while Gigante remained untouched and officially “incompetent.”13

Through this structure, Gigante perfected a model of distributed control that blended hierarchy with invisibility. Orders filtered through intermediaries; messages were delivered orally, coded, or conveyed through intermediaries to minimize surveillance risk.14 Associates rarely saw Gigante directly. Meetings were conducted under layers of insulation, and even when his name arose, subordinates often invoked euphemisms, “the Old Man,” “the Neighbor,” or simply “Chin.”15 His mystique was further amplified by the performative spectacle of his mental illness, creating an image so at odds with criminal leadership that many investigators dismissed him outright.

This architecture of deception not only delayed Gigante’s prosecution but fundamentally redefined the way the Genovese family operated. The reliance on front bosses diffused risk across multiple layers of management, ensuring that arrests or indictments of mid-level figures would not disrupt the family’s flow of revenue.16 In the eyes of law enforcement, the Genovese family became a ghost bureaucracy, seemingly leaderless yet unnervingly efficient. Federal wiretaps captured conversations acknowledging Gigante’s unseen control, but tangible proof of his authority remained elusive for more than a decade.17

By the early 1990s, however, the fortress began to crack. Informants such as Vincent “The Fish” Cafaro, once a high-ranking Genovese associate, disclosed the elaborate deception, confirming that Gigante had been the real boss all along.18 His dual strategy, feigned insanity and proxy governance, was finally exposed as the most sophisticated shield the American Mafia had ever devised. Still, its success could not be denied: for nearly fifteen years, Gigante managed to operate as one of the nation’s most powerful criminal leaders without ever appearing to lead.

The “Bathrobe” Act and Feigned Mental Incapacity

By the time Gigante formally consolidated his rule in the early 1980s, he had already begun staging the performance that would make him infamous. Residents of Greenwich Village grew accustomed to the sight of a disheveled man in pajamas and slippers, muttering to himself as he shuffled through the narrow streets between Sullivan and Thompson.19 To passersby, it appeared to be a sad spectacle of decline; to federal agents, it became a source of deep frustration. Each sighting undermined their efforts to portray Gigante as the calculating leader of a multimillion-dollar criminal enterprise. Yet the routine was no accident. From hospital admissions to psychiatric evaluations, Gigante built a paper trail of mental instability that insulated him from accountability.20

The façade extended into the courts. When prosecutors indicted him on racketeering charges in 1990, defense attorneys produced a decade’s worth of psychiatric reports asserting schizophrenia, dementia, and other disorders.21 Gigante was frequently admitted to St. Vincent’s Hospital in Manhattan and St. Elizabeth’s in Washington, D.C., undergoing evaluations that described him as “unfit to stand trial.”22 Doctors noted incoherent speech, memory loss, and childlike affect, all meticulously maintained symptoms. The act succeeded: proceedings were repeatedly delayed as judges debated his competence.23 One psychiatrist later testified that he could not recall a defendant who had “so successfully sustained the illusion of insanity” for so many years.24

For the Genovese organization, Gigante’s performance was more than a personal shield; it was a strategic deterrent. By projecting incapacity, he discouraged rivals within the Mafia from challenging his authority, while convincing law enforcement that he posed no active threat.25 Behind the scenes, his orders continued to flow through intermediaries. Associates later revealed that key meetings were timed around his “episodes,” with instructions relayed indirectly to preserve the illusion.26 The persona of “the Oddfather,” as tabloid journalists dubbed him, became both camouflage and brand; its absurdity masking lethal precision.

Gigante’s act ultimately collapsed under the weight of evidence. By 1997, hidden recordings and informant testimony demonstrated that his mental illness was a ruse.27 The federal court in United States v. Gigante concluded that his condition was “malingered and contrived for the purpose of evading justice.”28 The spectacle that had once charmed neighbors and confused psychiatrists now served as evidence of obstruction. Even in exposure, however, the “bathrobe act” remained a testament to his cunning: a performance so convincing that it paralyzed the justice system for more than a decade while he ruled from behind a veil of madness.

Operational Control and Criminal Enterprise Under Gigante

Behind the theater of insanity, the Genovese crime family functioned with astonishing precision. Gigante maintained a network of trusted lieutenants who managed the family’s traditional rackets (gambling, loansharking, labor racketeering, extortion, and construction kickbacks) without ever putting their boss in direct contact with criminal proceeds.29 The family’s stronghold stretched from Manhattan’s West Side to the New Jersey waterfront, embedded deeply within the unions of the International Longshoremen’s Association and the Laborers’ International Union of North America.30 Gigante’s reach extended into concrete supply firms, dock operations, and construction contracts, where his influence shaped who received jobs and at what price.31 Despite his supposed incapacity, meetings were scheduled in apartments and clubhouses across the city, where his word, delivered through intermediaries, was treated as law.

Federal wiretaps and informant reports later revealed how Gigante’s compartmentalized chain of command enabled him to remain insulated.32 Crew bosses collected earnings and filtered them upward through the family’s “administration,” a triad that included a consigliere and two acting underbosses.33 Each level minimized exposure to law enforcement by ensuring that no one could claim to have met directly with Gigante or received written orders.34 FBI surveillance recorded coded conversations between subordinates that hinted at directives “from the top,” but no recordings ever captured Gigante’s voice giving commands.35 In effect, he was the invisible center of a self-regulating organism, every part aware of his presence but shielded from it.

This structure proved remarkably durable. When the Commission Trial decimated other New York crime families, the Genovese organization remained largely intact.36 Prosecutors believed that Gigante’s policy of secrecy and limited exposure had saved the family from the same collapse that crippled the Gambino and Lucchese groups.37 Even when top lieutenants were indicted, replacements were groomed with little disruption to operations. By decentralizing decision-making and enforcing silence through fear and loyalty, Gigante transformed the Genovese family into a model of organized efficiency, a criminal bureaucracy operating with corporate discipline.38

Yet the very secrecy that had protected Gigante began eroding his control in the 1990s. Younger associates, less reverent toward the old ways, questioned the purpose of serving an unseen boss.39 Law enforcement intensified its efforts, deploying electronic surveillance and cultivating informants who could penetrate the family’s insular culture. The FBI’s “Operation Genovese” finally broke through, identifying financial transactions and coded messages that traced directly to Gigante’s circle.40 What emerged was a portrait of a criminal empire sustained as much by illusion as by fear, a network where the man who appeared most powerless wielded the most absolute authority.

The Breakdown and Prosecution

By the early 1990s, the elaborate web of deception that had protected Gigante for decades began to fray.41 The turning point came not from street violence or rival families, but from within, trusted insiders who grew weary of the secrecy that had long defined the Genovese organization. Cafaro, once a close lieutenant to Salerno, defected and became a government witness.42 His testimony confirmed what prosecutors had long suspected: Gigante, not Salerno, had been the true head of the family during the 1980s. Cafaro’s detailed accounts of coded meetings, financial distributions, and Gigante’s direct oversight pierced the veil that law enforcement had struggled to lift for years.43 With these revelations, the Department of Justice began assembling a comprehensive case to expose the Genovese hierarchy’s inner workings.

In May 1990, Gigante was indicted on federal racketeering charges alongside several senior family figures.44 The indictment alleged that he had overseen a vast criminal enterprise encompassing labor corruption, extortion, and bid-rigging across multiple states. Prosecutors described him as “the most powerful Mafia leader in America,”45 while his attorneys maintained that he was a mentally unfit, delusional old man. For years, the courts were gridlocked by competing psychiatric evaluations and procedural delays.46 The spectacle of “The Oddfather” wandering the streets in pajamas became nightly news fodder, symbolizing both the absurdity and frustration of trying to convict a man who had seemingly outwitted the entire justice system.

The stalemate persisted until 1996, when Judge Jack B. Weinstein of the Eastern District of New York ruled that Gigante was competent to stand trial.47 The decision was grounded in testimony from FBI agents, former associates, and medical experts who exposed the inconsistencies in his behavior, lucid and authoritative in private, incoherent and feeble only in public or court settings. The following year, a jury convicted Gigante of racketeering and conspiracy, sentencing him to twelve years in federal prison.48 Though diminished by age, he remained defiant, continuing to insist that his ailments were genuine even as evidence of his orchestration mounted.

Gigante’s imprisonment did little to halt federal scrutiny. In 2002, prosecutors indicted him again, this time for obstruction of justice, arguing that he had willfully perpetuated the fraud of mental illness to obstruct previous investigations.49 The plea negotiations that followed revealed a rare moment of candor: in 2003, Gigante admitted in court that he had feigned insanity for decades to avoid prosecution.50 The admission marked the final unraveling of his carefully constructed myth. It also represented one of the most extraordinary confessions in the history of organized crime, a calculated deceit so effective it had paralyzed law enforcement for nearly twenty years.

Vincent Gigante spent his remaining years in a federal medical facility in Springfield, Missouri, where he died on December 19, 2005, at the age of seventy-seven.51 His passing closed one of the last great chapters of the American Mafia’s golden age. The man who had once ruled the most secretive of New York’s Five Families from behind a mask of madness had outlasted nearly all of his contemporaries. In the end, his legacy was not merely that of a mob boss, but of a tactician who transformed deception into an art form, proving that in the underworld, power often survives longest when hidden in plain sight.

Evaluation of Legacy and Significance

Gigante’s reign over the Genovese crime family stands as one of the most sophisticated exercises in deception in American criminal history. His manipulation of image and institution blurred the line between madness and strategy, turning illusion into an operational doctrine.52 In contrast to flamboyant contemporaries like John Gotti, whose visibility hastened his downfall, Gigante mastered invisibility as a form of survival. His genius was bureaucratic rather than theatrical: he managed a vast criminal network not by public command but through whispers, intermediaries, and the performance of frailty. Law enforcement came to see him not simply as another Mafia boss, but as the embodiment of an evolved criminal ethos, one that thrived on ambiguity and restraint rather than spectacle.53

This quiet power reshaped the internal dynamics of organized crime. Under Gigante, the Genovese family operated more like a decentralized corporation than a traditional hierarchy.54 His use of front bosses created a leadership model that balanced authority with plausible deniability, ensuring the family’s continuity even in the face of systemic prosecution. The result was a criminal organization that remained remarkably stable throughout the 1980s and 1990s, avoiding the internecine warfare and collapse that plagued rival families. His methods echoed a broader shift in the American Mafia, from the flamboyance of mid-century bosses to the bureaucratized underworld of the late twentieth century, where invisibility became the ultimate currency of power.55

For prosecutors and investigators, Gigante’s long deception forced a reevaluation of how criminal enterprises were understood and pursued. Traditional strategies (wiretaps, surveillance, informants) proved insufficient against a structure designed to obscure decision-making.56 The Department of Justice adapted by focusing on financial forensics and organizational mapping, treating crime families less as personality-driven hierarchies than as adaptive networks. Gigante’s success, paradoxically, catalyzed the modernization of federal anti-racketeering efforts. His case underscored that organized crime, like any complex system, evolves under pressure, and that power can be most enduring when it disguises itself as weakness.57

In the end, Gigante’s legacy lies not only in the longevity of his rule but in the myth he crafted. The image of a shuffling old man mumbling to himself through Village streets endures as both absurd and profound, a symbol of how performance can outwit perception. He revealed that deception, when institutionalized, can be as potent as violence in maintaining control.58 Though his empire eventually fell to exposure and confession, his model of distributed power and strategic invisibility remains studied by law enforcement and historians alike. Gigante turned madness into method, illusion into order, and in doing so, transformed the criminal art of survival into a psychological masterpiece.59

Conclusion

Vincent Gigante’s story closes not with the triumph of a mythic criminal, but with the quiet unraveling of a man who had turned deception into an institution.60 For more than two decades, he orchestrated one of the most disciplined and enduring criminal enterprises in American history, hidden behind the guise of infirmity. His bathrobe walks through Greenwich Village became a daily ritual of misdirection, an opera of delusion staged for law enforcement, neighbors, and the nation itself. Beneath the muttering mask was a mind attuned to the mechanics of power: how to wield it, disguise it, and survive within it.61

Gigante’s performance, though eventually exposed, forced the justice system to confront its own limitations. The state, with its rules of evidence and burden of proof, was pitted against a man who weaponized ambiguity.62 His long deception illuminated a paradox at the heart of modern governance: that institutions devoted to transparency can be most easily confounded by what refuses to declare itself. When he finally confessed to feigning insanity, it was less an admission of guilt than a final act of control, Gigante, even in defeat, dictated the terms of truth.63

What remains of his legacy is not only the story of a Mafia boss but of a strategist who understood the human tendency to believe what it can see and to dismiss what it cannot.64 Gigante’s genius lay in exploiting that blindness. He transformed vulnerability into armor and confusion into command. His was a rule maintained by silence and sustained by illusion, a criminal kingdom built on the simplest principle of survival: that power endures longest when no one is certain who holds it.65

Appendix

Footnotes

- Selwyn Raab, Five Families: The Rise, Decline, and Resurgence of America’s Most Powerful Mafia Empires (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2005), 491.

- Ibid., 492; New York Times, “Vincent Gigante, Mob Boss Who Feigned Insanity, Dies at 77,” December 19, 2005.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation, “Vincent Gigante: Organized Crime Activities,” declassified case file summary, accessed November 2025, https://vault.fbi.gov/vincent-gigante.

- United States v. Gigante, 982 F. Supp. 140 (E.D.N.Y. 1997).

- Raab, Five Families, 493.

- Jerry Capeci, Chin: The Life and Crimes of Mafia Boss Vincent Gigante (New York: Pinnacle Books, 2016), 117–121.

- Capeci, Chin, 132–134.

- Raab, Five Families, 496.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation, “Vincent Gigante: Organized Crime Activities.”

- Capeci, Chin, 141–144.

- New York Times, “Anthony Salerno Convicted in Mafia Commission Trial,” November 20, 1986.

- Capeci, Chin, 150.

- United States v. Salerno, 481 U.S. 739 (1987).

- Capeci, Chin, 153–156.

- Raab, Five Families, 499.

- United States v. Gigante, 982 F. Supp. 140 (E.D.N.Y. 1997).

- Federal Bureau of Investigation, “Vincent Gigante: Organized Crime Activities.”

- New York Times, “Vincent ‘Fish’ Cafaro Testifies in Mob Trial,” April 8, 1991.

- Raab, Five Families, 502.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation, “Vincent Gigante: Organized Crime Activities.”

- Capeci, Chin, 167–172.

- New York Times, “Vincent Gigante, Mob Boss Who Feigned Insanity, Dies at 77,” December 19, 2005.

- United States v. Gigante, 982 F. Supp. 140 (E.D.N.Y. 1997).

- Capeci, Chin, 178.

- Raab, Five Families, 505.

- Capeci, Chin, 182.

- New York Times, “Mob Boss Finally Ruled Competent to Stand Trial,” July 25, 1996.

- United States v. Gigante, 982 F. Supp. 140 (E.D.N.Y. 1997).

- Capeci, Chin, 185–189.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation, “Vincent Gigante: Organized Crime Activities.”

- New York Times, “Gigante Indicted in Racketeering Case Involving Waterfront Unions,” May 31, 1990.

- Raab, Five Families, 508–509.

- United States v. Gigante, 982 F. Supp. 140 (E.D.N.Y. 1997).

- Capeci, Chin, 191–193.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation, “Vincent Gigante: Organized Crime Activities.”

- New York Times, “Anthony Salerno Convicted in Mafia Commission Trial,” November 20, 1986.

- Raab, Five Families, 511.

- Capeci, Chin, 198–201.

- Raab, Five Families, 514.

- United States v. Gigante, 982 F. Supp. 140 (E.D.N.Y. 1997).

- Raab, Five Families, 515.

- New York Times, “Vincent ‘Fish’ Cafaro Testifies in Mob Trial,” April 8, 1991.

- Capeci, Chin, 213–218.

- United States v. Gigante, 982 F. Supp. 140 (E.D.N.Y. 1997).

- New York Times, “Gigante Indicted in Racketeering Case Involving Waterfront Unions,” May 31, 1990.

- Capeci, Chin, 222–225.

- New York Times, “Mob Boss Finally Ruled Competent to Stand Trial,” July 25, 1996.

- United States v. Gigante, 982 F. Supp. 140 (E.D.N.Y. 1997).

- New York Times, “Mob Boss Faces New Charge of Obstruction,” May 24, 2002.

- New York Times, “Mob Boss Admits Faking Insanity to Avoid Jail,” April 8, 2003.

- New York Times, “Vincent Gigante, Mob Boss Who Feigned Insanity, Dies at 77,” December 19, 2005.

- Raab, Five Families, 519.

- Capeci, Chin, 243–245.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation, “Vincent Gigante: Organized Crime Activities.”

- Raab, Five Families, 520.

- United States v. Gigante, 982 F. Supp. 140 (E.D.N.Y. 1997).

- New York Times, “How the Feds Finally Broke the Oddfather’s Wall of Silence,” June 2, 2004.

- Capeci, Chin, 252–254.

- Raab, Five Families, 523.

- Raab, Five Families, 526.

- Capeci, Chin, 258–261.

- United States v. Gigante, 982 F. Supp. 140 (E.D.N.Y. 1997).

- New York Times, “Mob Boss Admits Faking Insanity to Avoid Jail,” April 8, 2003.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation, “Vincent Gigante: Organized Crime Activities.”

- Raab, Five Families, 528.

Bibliography

- Capeci, Jerry. Chin: The Life and Crimes of Mafia Boss Vincent Gigante. New York: Pinnacle Books, 2016.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation. “Vincent Gigante: Organized Crime Activities.” Declassified case file summary. Accessed November 2025. https://vault.fbi.gov/vincent-gigante.

- Raab, Selwyn. Five Families: The Rise, Decline, and Resurgence of America’s Most Powerful Mafia Empires. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2005.

- United States v. Gigante, 982 F. Supp. 140 (E.D.N.Y. 1997).

- United States v. Salerno, 481 U.S. 739 (1987).

- New York Times. “Anthony Salerno Convicted in Mafia Commission Trial.” November 20, 1986.

- ———. “Gigante Indicted in Racketeering Case Involving Waterfront Unions.” May 31, 1990.

- ———. “Mob Boss Finally Ruled Competent to Stand Trial.” July 25, 1996.

- ———. “Vincent ‘Fish’ Cafaro Testifies in Mob Trial.” April 8, 1991.

- ———. “Mob Boss Faces New Charge of Obstruction.” May 24, 2002.

- ———. “Mob Boss Admits Faking Insanity to Avoid Jail.” April 8, 2003.

- ———. “How the Feds Finally Broke the Oddfather’s Wall of Silence.” June 2, 2004.

- ———. “Vincent Gigante, Mob Boss Who Feigned Insanity, Dies at 77.” December 19, 2005.

Originally published by Brewminate, 11.11.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.