In the ancient Roman world, sexual pleasure was a cause for celebration rather than a source of shame.

By Meilan Solly

Associate Digital Editor, History

Smithsonian Magazine

In the 19th century, the archaeologists tasked with excavating Pompeii and Herculaneum ran into a problem: Everywhere they turned, they found erotic art, from frescoes of copulating couples to sculptures of nude, well-endowed gods.

At a time when sex was widely considered shameful or even obscene, officials deemed the images too explicit for the general public. Instead of placing the artifacts on view, staff at the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli stashed them in a secret room closed to all but scholars and, according to Atlas Obscura, male visitors willing to bribe their way in. Between 1849 and 2000, the works remained largely hidden from the public.

Not anymore. A new exhibition at the Archaeological Park of Pompeii titled “Art and Sensuality in the Houses of Pompeii” draws on selections from the secret room and other sensual images unearthed in the ancient city to demonstrate the ubiquity of erotic imagery in the Roman world.

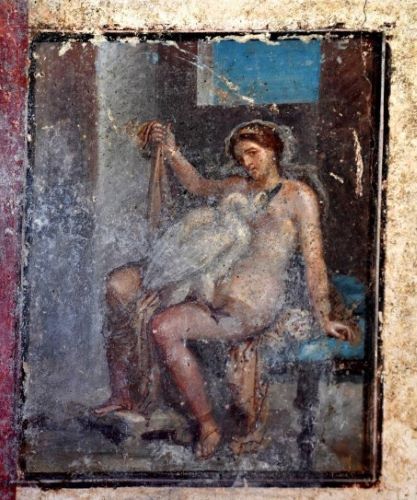

The show’s marquee attraction is a fresco of the myth of Leda and the swan. Discovered in 2018, the scene depicts the moment when the god Zeus, disguised as a swan, either rapes or seduces Leda, queen of Sparta. Later, legend holds, Leda laid two eggs that hatched into children: Pollux and Helen, whose “face … launched a thousand ships” by sparking the Trojan War.

Painted on the wall of a Pompeiian bedroom, the artwork shows a nude Leda smiling invitingly as a swan nuzzles against her chest.

“[The scene] sends a message of sensuality,” Massimo Osanna, then-director of the archaeological park, told CNN’s Barbie Latza Nadeau and Hada Messia in 2019. “It means, ‘I am looking at you and you are looking at me while I am doing something very, very special.’ It is very explicit. Look at her naked leg, the luxurious sandal.”

The House of Leda and the Swan fresco is one of 70 artworks featured in the exhibition, which is accompanied by an app and a guide contextualizing the show for children. Per a statement, sensual art—from a fresco of Priapus, the Greek god of fertility and male genitalia, weighing his penis on a scale, to a pair of medallions depicting satyrs, cupids and nymphs found on a ceremonial chariot outside of Pompeii last year—appeared in both private homes and public spaces such as taverns, baths and brothels.

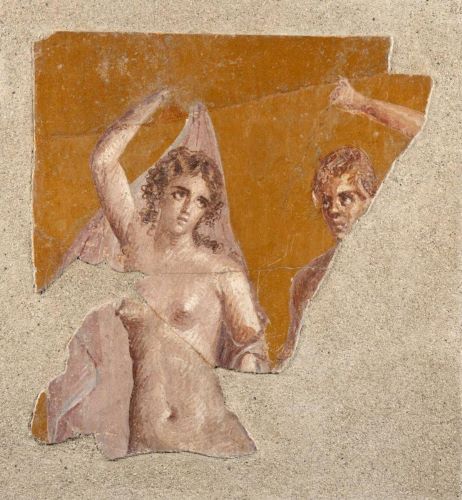

“Eroticism was everywhere … thanks to the influence of the Greeks, whose art heavily featured nudity,” the park’s current director, Gabriel Zuchtriegel, tells Tom Kington of the London Times.

Speaking with Jez Fielder of Euronews, exhibition curator Maria Luisa Catoni says that Pompeii’s depictions of sex and nudity conveyed “values like being culturally elevated, being part of a larger high culture” exemplified by the Romans’ predecessors, the ancient Greeks. At a time when polytheism, not Christianity, was the norm, sexual pleasure—embraced proudly by the very gods the Romans worshipped—was cause for celebration.

“The Greeks approached the human form with no sense that nudity was inherently shameful,” wrote Geoffrey R. Stone, author of Sex and the Constitution, for the Washington Postin 2017. “To the contrary, the phallus was a potent symbol of fertility, a central theme in Greek religion.”

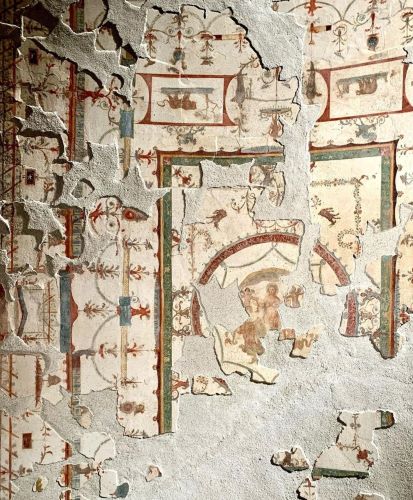

“Art and Sensuality” is laid out like a typical Roman home. Visitors enter through the atrium, a courtyard and reception area featuring a fresco of Narcissus, the young man who fell in love with his own reflection, and a statue of Priapus. Cubicula, or bedrooms, encircle the atrium, showcasing intimate scenes of couples having sex. Highlights of this section include a reassembled, newly restored ceiling from the House of Leda and the Swan and three reconstructed bedroom walls from another Pompeiian villa.

In the triclinium, or dining hall, images of teenagers appear, alluding to the Greek tradition of pederasty, in which older men had romantic or sexual relationships with adolescent boys. Though accepted in ancient times, the practice is clearly at odds with modern mores. As Stone noted for the Post, “The Greek ideal of beauty was embodied most perfectly in the male youth.”

The final area of the house, an open-air courtyard known as the peristylium, takes its cue from the space’s melding of indoors and outdoors, using images of intersex people and hybrid creatures like centaurs to symbolize the blurred boundaries “between genders … or humans and animals,” per the statement.

“Scholars have tended to interpret any rooms decorated with [erotic] scenes as some kind of brothel,” Zuchtriegel tells the Guardian’s Angela Giuffrida. “But there was also space for [sex] inside homes.”

By 79 C.E., when the eruption of Mount Vesuvius brought Pompeii’s heyday to an abrupt end, Christianity had begun to take hold across the Roman Empire. With the religion’s rise came a shift in how people viewed sex; as Elaine Velie writes for Hyperallergic, Christian conceptions of sex as obscene or shameful prompted the 19th-century archaeologists who excavated the ancient city to hide its erotic artifacts from the public.

“This was another time and a different society. It was not so strange to show a masculine phallus,” Osanna told CNN in 2019. “The people of Pompeii used this imagery a lot. … It was really a society where sex was not something to consume just in a private space.”

Originally published by Smithsonian Magazine, 04.28.2022, reprinted with permission for educational, non-commercial purposes.