By Murray N. Rothbard

The Massachusetts colony was organized in towns. The church congregation of each town selected its minister. Unlike the thinly populated, extensive settlement of Virginia, the clustering in towns was ideal for having the minister and his aides keep watch on all the inhabitants. Although the congregation selected the minister, the town government paid his salary; in contrast to the poorly paid clergy of the Southern colonies, the salary was handsome indeed. Out of it the minister could maintain several slaves or indentured servants and amass a valuable library. The minister—himself a government official—exerted enormous political influence in the community, and only someone whom he certified as “godly” was likely to gain elected office. The congregation was ruled, not democratically by the members, but rather by its council of elders. Also highly important was the minister who functioned as “church teacher,” specializing in doctrinal matters.

Since only church members could vote in political elections, the requirements for admission became a matter of concern for every inhabitant. These requirements were rigorous. For one thing, the candidate had to satisfy the minister and elders of his complete adherence to pure doctrine and of his satisfactory personal conduct. And, once admitted, he was always subject to expulsion for deviations in either area.

To the saints and their leaders, any idea of separation of church and state was anathema. As the Puritan synod put it in their Platform of Church Discipline(1648):

“It is the duty of the magistrate to take care of matters of religion…. The end of the magistrate’s office is …godliness.” It is the duty of the magistrate to punish and repress “idolatry, blasphemy, heresy, venting corrupt and pernicious opinions …open contempt of the word preached, profanation of the Lord’s Day.”

Should any congregation dare to “grow schismatical” or “walk incorrigibly or obstinately in any corrupt way of their own,” the magistrate was to “put forth his coercive power.” And if the state was to be the strong coercive arm of the church, so the church, in turn, was to foster in the public the duty of obedience to the state rulers:

“Church government furthereth the people in yielding more hearty…obedience unto the civil government.”

From this attitude, it followed for the Puritan that any rebel against the civil government was a “rebel and traitor” to God, and of course any criticism of, let alone rebellion against, Puritan rule was also a sin against God, the author of the plan for Puritan hegemony. So insistent indeed were the Puritans on the duty of obedience to civil government that the content of its decrees became almost irrelevant. As Rev. John Davenport, a leading Puritan divine, put it:

“You must submit to the rulers’ authority, and perform all duties to them whom you have chosen… whether they be good or bad, by virtue of their relation between them and you.”

Naturally, John Winthrop, who helped govern Massachusetts for twenty years after its inception, agreed with this sentiment. To Winthrop, natural liberty was a “wild beast,” while correct civil liberty meant being properly subjected to authority and restrained by “God’s ordinances.”

Perhaps the bluntest expression of the Puritan ideal of theocracy was the Rev. Nathaniel Ward’s The Simple Cobbler of Aggawam in America (1647). Returning to England to take part in the Puritan ferment there, this Massachusetts divine was horrified to find the English Puritans too soft and tolerant, too willing to allow a diversity of opinion in society. The objective of both church and state, Ward declaimed, was to coerce virtue, to “preserve unity of spirit, faith and ordinances, to be all like-minded, of one accord; every man to take his brother into his Christian care…and by no means to permit heresies or erroneous opinions.” Ward continued:

“God does nowhere in His word tolerate Christian States to give toleration to such adversaries of His truth, if they have power in their hands to suppress them . . . He that willingly assents to toleration of varieties of religion his conscience will tell him he is either an atheist or a heretic or a hypocrite, or at best captive to some lust. Poly-piety is the greatest impiety in the world… To authorize an untruth by a toleration of State is to build a sconce against the walls of heaven, to batter God out of His chair.”

And so the Puritan ministry stood at the apex of rule in Massachusetts, ever ready to use the secular arm to enforce its beliefs against critics and false prophets, or even against simple lapses from conformity.

To enforce purity of doctrine upon society, the Puritans needed a network of schools throughout the colony to indoctrinate the younger generation. The Southern colonies’ individualistic attitude toward education was not to be tolerated. Also, the clusters of town settlements made schools far more feasible than it did among the widely scattered rural population of the Southern colonies.

One of the essential goals of Puritan rule was strict and rigorous enforcement of the ascetic Puritan conception of moral behavior. But since men’s actions, given freedom to express their choices, are determined by their inner convictions and values, compulsory moral rules only serve to manufacture hypocrites and not to advance genuine morality. Coercion only forces people to change their actions; it does not persuade people to change their underlying values and convictions. And since those already convinced of the moral rules would abide by them without coercion, the only real impact of compulsory morality is to engender hypocrites, those whose actions no longer reflect their inner convictions.

Kissing one’s wife in public on a Sunday was also outlawed. A sea captain, returning home on a Sunday morning from a three-year voyage, was indiscreet enough to kiss his wife on the doorstep. For this he was forced to sit in the stocks for two hours for this “lewd and unseemly behavior on the Sabbath Day.”

Not only were nonreligious activities outlawed on Sundays, but attendance at a Puritan church was compulsory as well. Fines were levied for absence from church, and the police were ordered to search through the towns for absentees and forcibly haul them to church. Falling asleep in church was also outlawed and whipping was the punishment for repeated offenses.

Gambling of any kind was strictly forbidden. The law declared: “Nor shall any person at any time play or game for any money… upon penalty of forfeiting treble the value thereof, one half to the party informing and the other half to the treasurer.” Yet, as so often happens in this world, what was so sternly prohibited to private individuals was permitted to government. Thus, government was permitted to raise revenue for itself by running lotteries. To government, in short, was given the compulsory monopoly of the gambling and lottery business. Cards and dice were, of course, prohibited as gambling. Also prohibited, however, were games of skill at public houses, such as bowling and shuffleboard, such activities being considered a waste of time by the people’s self-appointed moral guardians in the government.

Idleness, in fact, was not just a sin, but also a punishable misdemeanor–at any time, not only on Sunday. If the constable discovered anyone, singly or in groups, engaged in such heinous behavior as coasting on the ice, swimming, or sneaking a quiet smoke, he was ordered to report to the magistrate. Time, it seems, was God’s gift and therefore always to be used in His service. A sin against God’s time was a crime against the church and state.

Drinking, oddly enough, was not completely outlawed, but drunkenness was, and subject to a fine. The practice of drinking toasts was outlawed in 1639, because of its supposedly pagan origin and because, once a man has begun to drink a toast, he is on the road to perdition; “drunkenness, uncleanness, and other sins quickly follow.” And yet the stern guardians of the public morality had their troubles, for decades later we find ministerial complaints that the “heathenish and idolatrous practice of health-drinking is too frequent.”

Women and children, as might be expected, were treated extremely harshly by the Puritan commonwealth. Children were regarded as the virtually absolute property of their parents, and this property claim was rigorously enforced by the state. If any child be disobedient to his parents, any magistrate could haul him into court, and punish the little criminal with a maximum of ten lashes for each offense. Should the pattern of disobedience persist into adolescence, the parents, as provided by the law of 1646, were supposed to bring the youth to the magistrate. If convicted of the high crime of stubbornness and rebelliousness, the son was to be duly executed. Happily, it is likely that this particular law, on the books for over thirty years, was rarely, if ever, put into effect by the parents.

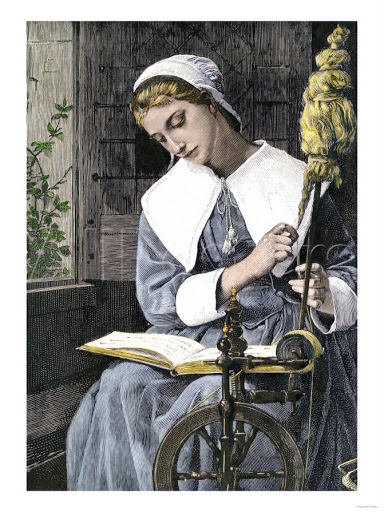

Women were viewed as instruments of Satan by the Puritans, and severe laws were passed outlawing women’s apparel that was either immodest or so showy as to indicate the sin of “pride of raiment.” “Immodesty” included the wearing of short-sleeved dresses, “whereby the nakedness of the arm may be discovered”—a practice duly outlawed in 1656.

In outlawing “pride of raiment,” women were not discriminated against by the Puritans; men too felt the heavy arm of the state. In 1634 the General Court began the practice of outlawing finery of dress for either sex, including “immodest fashions . . . with any lace on it, silver, gold or thread,” hat bands, belts, ruffs, beaver hats, and many other items of adornment.

In 1639more items of sin were added: for example, ribbons, shoulder bands, and cuffs—these nonutilitarian items being of “little use or benefit, but to the nourishment of pride.” Excessive finery was subject to heavy fines, and the law was extensively enforced. Thus, in one year, Hampshire County hauled thirty-eight women and thirty men into court for illegal finery, silk being an especially popular sin. One woman was punished “for wearing silk in a flaunting garb, to the great offense of several sober persons.”

Even the wearing of one’s hair long—an old Cavalier practice condemned by the Puritans, who were therefore called Roundheads—was placed under interdict. The General Court repeatedly condemned flowing hair as a dangerous vanity. Many Puritan divines ranked “pride in long hair” fully as sinful as gambling, drinking, or idleness. One citizen, fined for daring to build upon unused government land, was offered a remission of half the amount if he would only cut off the long hair off his head into a civil frame.

Hair righteousness, however, never had much of a chance even in godly Massachusetts, for some of the major leaders of the colony, including Governor Winthrop and John Endecott, persisted in the sin of long hair.

Mixed dancing only came to the colony late in the century, but was promptly condemned as frivolous, immoral and a waste of time Boston, upon hearing complaints, closed down a dancing school.

Originally published by the Mises Institute, 1999 (1, 174-181), under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.