Exploring the varied forms of masculinity and femininity seen in the written sources.

By Lee Colwill

Library Assistant and PhD Student

University of Cambridge

Introduction

This chapter explores four remarkable burials in Late Iron Age Scandinavia, looking beyond the static scene uncovered at the point of excavation to the funerary processes that created the sites. The majority of the graves discussed here have been associated with the magico-religious practice of seiðr; the chapter therefore also explores the evidence for connecting this practice with transgressive gender performances, taking into account the problematic literary evidence as well as the difficulty in interpreting the archaeological material. Based on an analysis of these burials, the chapter argues that an approach to gender archaeology which moves beyond assumptions of a fixed binary inherent to the physical body can only enrich our understanding of the past.

Appropriation of the medieval period – and especially the history of pre-Christian Scandinavia – for white supremacist ends is well attested.1 Modern völkisch groups (nationalist and ethnocentric Norse neo-pagans) have also used their own idealized views of the early history of Scandinavia to justify cis- and heteronormative approaches to gender roles in the modern day.2 Ideas about white supremacy and gender essentialism often go hand-in-hand. One way of disrupting this paradigm is to emphasize the ways in which gender in pre-Christian Scandinavia was far queerer (in all senses of the word) than the traditional narrative acknowledges.

This chapter seeks to challenge the ahistorical idea, still widespread in the popular imagination, that Late Iron Age Scandinavia – the area of modern-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden, in approximately the eighth to the tenth century CE – was a homogenous place where white men lived lives defined by hypermasculine aggression, white women were confined to the domestic sphere, and queer people and people of colour were nowhere to be seen. In recent decades, a number of scholars have attempted to counteract this view, exploring, among other topics, the construction of race in Icelandic sagas, the potential for queer readings of Norse mythology, and the varied forms of masculinity and femininity seen in the written sources.3

Focusing on the question of how gender was negotiated in the Late Iron Age, this chapter draws on evidence from four burials from across continental Scandinavia, dated to the ninth and tenth centuries. Burials can be interpreted as narratives of veneration, with the procedures of the funerary rite forming a ‘text’ that can be read.4 It is in this context that the ship burials at Oseberg and Kaupang, the chamber grave Bj. 581 at Birka, and the cremations at Klinta are discussed. The sites explored here have been chosen in part because their complexity lends itself well to this kind of interpretation, but also because their comparatively good preservation and detailed documentation make it possible to conduct in-depth analysis in a way that is not often the case with Scandinavian burials. All of these graves raise questions about the applicability of a strict gender binary to the communities which produced them. In particular, individuals from the majority of these graves have been connected with the practice of seiðr, a form of magic which, it is often argued, involved transgressive gender performances as part of its rituals.

Transgender Archaeology

The past gains meaning for modern interpreters through its connections to the present. This chapter therefore uses the terms ‘transgender’ and ‘genderqueer’ in their modern senses to refer to individuals who today would likely be perceived as belonging to these categories.5 This is not to say that all such figures would have recognized themselves, or been recognized by their communities, as crossing from one gender category to another. Rather, our understanding of gender roles in the Late Iron Age may require significant revision in the light of recent discoveries such as the genomic sexing of Birka grave Bj. 581, a ‘warrior’ grave previously assumed to be that of a man, whose occupant proved to have XX chromosomes.6 This example is a particularly well-publicized one, but is far from the only case where identities read into grave goods seem incongruous with identities read into the sexed body.7 In such cases, a transgender reading is one possibility, though seldom the one adopted.

Archaeological sexing is far from a fail-safe tool, particularly for exploring the often-intangible concept of identities. Remains are sexed osteologically (by examining the size and shape of the bones) or on the basis of genomic analysis (‘genomic’ or ‘chromosomal sexing’), and assigned to a particular sex, most frequently a binary male/female one, on this basis. The inaccuracy of such an approach has been criticized by numerous gender archaeologists for its frequent disregard of the possibility of intersex remains, not to mention its essentialist focus on the physical body over social identity.8 Moreover, it is virtually impossible to accurately assign sex to children and adolescents based on osteological sexing alone, calling into further doubt the value of dividing remains into strict binary categories to begin with. Genomic sexing is likewise not the magic bullet it is often presented as, offering a ratio of X and Y chromosomes from which a chromosomal arrangement is extrapolated. As Skoglund et al. point out, chromosomal arrangements other than XY and X X are difficult to detect by this method.9

Throughout this chapter, the term ‘sex’ is used in reference to the char-acteristics of the physical body that Western medicine has deemed to be either ‘male’ or ‘female’. Given that questions of internal identity can only ever be speculative when it comes to burials, ‘gender’ here is used in the sense of ‘social gender’ – a role produced in social contexts, requiring both performance and interpretation.10

Mortuary Narratives

Burials are not static; rather, what is excavated are the remains of the ‘final scene’ in a lengthy process which draws together many actors – human, animal and object – in order to stage the drama of the funerary ritual.11 As a general rule, items found in graves did not arrive there by chance, but were chosen and arranged for a reason by those who buried the deceased. Though it is impossible to be sure what motivations lay behind any given burial, the intentionality of funerary practices makes them a form of narrative through which to approach the mentalities of the society which created them. As Howard Williams has noted, the burial process creates a time and space in which identities are in flux as the living determine how they will remember the dead.12 Actions taken during the funeral can therefore cement certain identities while obscuring others. Moreover, the objects in play during these rituals are not merely passive things to be acted upon; rather, they work in dialogue with human actors in much the same way as has been argued for oral and written narratives, to express and negotiate identities and ideologies.13 It is this context that grave goods should be interpreted.

The best-documented graves from pre-Christian Scandinavia are frequently those of high-status individuals. This is due to the nature of find preservation: an unmarked grave consisting only of organic material subject to decay is much more difficult to trace a thousand years later than an elaborate burial in a mound with plenty of metal grave goods. Burials of slaves and children are therefore only known in this period in Scandinavia from their inclusion in multiple-person graves.14 The burials discussed below all fall into the category of high-status burials, and the majority of their occupants seem to have been figures of religious significance. Their funerary procedures therefore form a type of hagiographic narrative: a text of veneration, testifying to their singular status and the respect – sometimes tinged with fear – that they were accorded as a result.

When it comes to exploring gender identity through grave goods, it is difficult to avoid the sort of circular reasoning which declares, for example: ‘oval brooches are items of female dress, so graves containing them must be women’s graves; we know oval brooches are items of female dress because we find them in women’s graves’. A partial solution to the problem is offered by increasingly accurate methods of osteological sexing, although, as noted above, such methods are often inadequate when it comes to recognizing intersex remains. However, when gender is decoupled from sex, as many archaeologists argue it should be in order to more fully understand past societies, approaches that rely on the physical body do not suffice.15 Here the idea of normative domains can be useful: if we have grave goods which, in the vast majority of cases, are found with remains of one particular osteological sex, it is reasonable to conclude that this society associated these items with a particular gender – and that they viewed this gender as largely linked to the sexed body. Unfortunately, when it comes to material from the Iron Age, many graves excavated in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries have only been ‘sexed’ on the basis of grave goods, rather than through osteological analysis, making it extremely difficult to build an accurate picture of which grave goods should be associated with a given sex.16

As the recent results from the Birka chamber grave Bj. 581 show, this sort of grave good-based ‘sexing’ is far from sound. Bj. 581 was initially sexed as male when it was excavated in the late nineteenth century on the grounds that the burial was a typical ‘warrior’ grave, complete with a full set of weapons.17 However, genomic sexing of the remains revealed that the person buried in Bj. 581 almost certainly had X X chromosomes.18 Given the poor preservation of human remains in Scandinavian burials, and the relative newness of the technology to perform genomic sexing, very few graves have been sexed in this way, and it is therefore impossible to say how many more graves may have similar ‘incongruities’ between grave goods and remains.

‘Seiðr’: A Queer Sort of Magic?

As three of the graves discussed below have been interpreted as those of seiðr practitioners, it is worth pausing here to give a brief overview of what is meant by the term seiðr. In written sources from medieval Scandinavia, all of which significantly post-date the region’s conversion to Christianity, this word is used to mean ‘magic’, frequently in a pejorative sense, and is often found in accounts of magic performed in Scandinavia before the Conversion. There are only a handful of detailed accounts of what seiðr might have involved. The most in-depth of these are Ynglinga saga (The Saga of the Ynglings), an account of the legendary kings of Scandinavian pre-history, and Eiríks saga rauða (The Saga of Eirik the Red), which features an episode of magic and counter-magic in the Norse settlement in Greenland. Both of these accounts present seiðr practitioners as occupying respected positions in society, with the Odin of Ynglinga saga presented as a human warrior, ruler, and powerful sorcerer, while Thorbjorg ‘little-witch’ in Eiríks saga is the possessor of many fine objects, treated as an honoured guest wherever she visits. However, both sagas evince a certain amount of discomfort with these figures’ magical practices. When Thorbjorg requests the assistance of a woman who knows chants conducive to her magic, the only such woman present tells her that she is unwilling to take part because she is a good Christian.19 In Ynglinga saga, the author’s distaste for seiðr is more apparent. Here, Odin’s magical talents include the malicious ability to cause sickness and madness in men. We are then told that seiðr was taught to Odin by Freyja (usually considered a goddess, but here called a ‘blótgyðja’[sacrificial priestess]) and that the practice ‘brought with it so much perversity that it was thought shameful for men to practise it’.20 This does not appear to have dissuaded Odin, and other sources attest to his seiðr-working. In the mythological poem Lokasenna (Loki’s Flyting), for example, the troublesome god Loki accuses Odin of having performed magic chants and ‘beaten a drum like a witch […] and that I thought a mark of perversity’.21

Since all written accounts of seiðr date from several centuries after Scandinavia’s conversion to Christianity, their relationship to any historical reality of magico-religious practices is highly debatable.22 In the Ynglinga saga account of Odin’s shapeshifting and use of companion animals, such as the two ravens who bring him news, scholars have seen a connection to shamanic practices of the circumpolar region, such as those documented by eighteenth- and nineteenth-century ethnographers among the Saami and the native peoples of Siberia. Clive Tolley’s comparative study of shamanic traditions and the Norse written material concludes that, though there may be shamanic elements in the later accounts of seiðr, there is insufficient evidence to interpret the pre-Christian practice as a shamanic one.23 However, a number of archaeologists point to the presence of objects such as the cannabis seeds and rattles found in the Oseberg ship burial as evidence that ritual practitioners of the Late Iron Age sought to induce shamanic trances.24 One outcome of this association between seiðr and shamanism has been the interpretation of seiðr as an intrinsically queer practice, drawing (unfortunately, often unnuanced) parallels with indigenous American gender systems to posit the idea of a ‘third gender’ for seiðr practitioners.25

While the inherent queerness of seiðr has been overstated, its portrayal in later written sources, combined with evidence from the archaeological record, does suggest that at least some of its practitioners inhabited a gender outside of a male/female binary. This has often been conceptualized by scholars as a practitioner gaining power for the duration of a seiðr ritual by ‘transgressing’ binary gender categories, though Miriam Mayburd has argued that power was instead gained through more continuous occupation of a liminal gender position.26 Though later written narratives treat the practice of seiðr as despicable for its association with improper gendered behaviour, this does not accord with the archaeological record. The graves of those suspected to be seiðr practitioners are often highly elaborate, deliberately emphasizing their inhabitants’ magical prowess, rather than seeking to hide it as a shameful secret. The written sources thus appear to demonstrate an attempt by writers in a Christian context to reconcile their understanding of their forebears’ magico-religious practices with changing ideas about acceptable gender performance. It is therefore probable that seiðr in the Iron Age did involve some sort of queer gender performance, not necessarily practised by all seiðr specialists, and perhaps only performed as part of short-term rituals in other cases, but nonetheless sufficiently present to be memorialized as part of the mortuary process.

The Queerly Departed

Oseberg Ship Burial, Vestfold, Norway (c.834 CE)

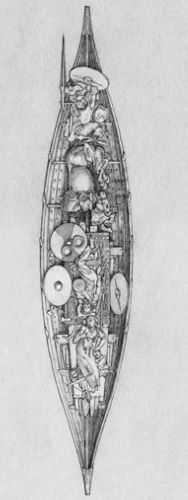

Death is a profound moment of change for those who knew the deceased. In this time of flux, the rituals of the funeral help to structure the ways in which the surviving community remembers the deceased. One example of mortuary behaviour as an ongoing process rather than a single, self-contained action can be seen in the ship burial from Oseberg, in the Vestfold region of Norway. This spectacular monument consisted of a ship, 21.6m in length, with a tent-like chamber on its deck in which two bodies were placed, surrounded by a huge variety of grave goods. On the foredeck, wooden items seem to have been heaped somewhat haphazardly, accompanied by a large number of animal sacrifices.27 The ship was then enclosed in a turf mound. These arrangements were made around 834 CE, based on dendrochronological analysis of the burial chamber.

The grandeur of the burial originally led it to be identified as that of a queen, perhaps the legendary Queen Ása, mentioned in Ynglinga saga as ruling part of southern Norway in the ninth century. However, more recent studies of the grave have rejected this identification. Instead, it is generally accepted that this is the grave of at least one magic-worker, and perhaps two. This interpretation is based on the presence of a number of items in the grave, perhaps most obviously a wooden rod or staff of the kind often associated with seiðr.28 The fact that this was accompanied by cannabis seeds, potentially used to induce a trance-like state, and metal rattles, which may have played a part in the ritual performance of seiðr, suggests that the community at Oseberg wished to remember these people as ritual specialists.29 This view is also supported by the fragments of tapestry which survive from the burial, which show figures in long robes, some with the heads of animals, apparently directing human sacrifice.

Considering the sense of supernatural significance evoked by this burial, the time it took to create is particularly relevant to the narrative underlying the grave. There has been considerable debate on this matter, with some archaeologists arguing that the differences between the fore and aft halves of the mound indicate that the aft half of the ship was covered first, while the foredeck, along with access to the burial chamber, was left exposed for many months, or even years.30 Terje Gansum argues that this would have allowed the local community to continue to visit their dead.31 This idea is supported by the ‘anchoring’ of the ship to a large rock as part of the burial process, suggesting that, despite their burial on a means of transportation, it was hoped that these two people would continue to be a presence in their community after death. However, evocative as this interpretation is, Sæbjørg Walaker Nordeide’s re-examination of the original excavation reports concludes that this supposed visitation period could not have taken place, as all botanical evidence from the turf, as well as the contents of the sacrificial animals’ stomachs, points to the entire construction taking place in autumn.32

Even proponents of the idea of a months-long ritual acknowledge that when the time came to seal up the burial, this was done with almost unseemly haste. In contrast to the careful construction of the ship itself, the entry to the central chamber was boarded up with mismatched pieces of wood, in some cases hammered in with such rapidity that the nails broke and were left in the wood.33 Moreover, the offerings on the foredeck seem to have been piled up in a careless fashion, with no effort made to protect the more delicate items from the heavier ones thrown on top. This stands in sharp contrast to the level of care and respect needed to offer up a spectacular ship, numerous animals, and many rare and valuable items, not to mention the investment of time and labour needed to construct a mound to cover a 21.6 m ship. The rock the Oseberg ship was anchored to also takes on a more ambiguous meaning: did the people who constructed the burial want to keep these two individuals in the community, or did they more specifically want to ensure that they remained inside the mound? The speed with which the bodies were sealed away under multiple layers of wood and turf points towards the latter.

The sumptuous components of the burial set against the hasty, almost slapdash actions taken apparently as the conclusion of the initial funerary rites tells a narrative of both veneration and fear. At Oseberg, we see both a deliberate deconstruction of the natural order and a breaking down of categories: a hill raised by human hands; a ship on land, tethered and im-mobile; two figures whose dead bodies command both immense respect and terrible fear. The narrative told here is therefore not one of straightforward admiration, but rather of the powerful mix of emotions that can come from interaction with the supernatural.

I have so far avoided gendering the two people interred at Oseberg because it is my contention that the older of these individuals could plausibly be read as transgender, in modern terms at least. Although the recovered remains are incomplete, both skeletons have been osteologically sexed as female. From his examination of the older individual’s remains, the osteologist Per Holck has suggested that this person may have had Morgagni-Stewart-Morel syndrome.34 This syndrome is characterized in skeletal remains by a thickening of the front of the skull, and can result in more body hair – including facial hair – and a deeper voice than is typical for cis women. It is therefore possible that this person was not perceived as a woman by the society in which they lived, and that their social gender was male, or a gender not recognized under a modern Western binary. Such an interpretation may also help to explain the apparently ‘masculine’ grave goods present in the burial, such as the harness mounts and belt fittings, which Fedir Androshchuk has interpreted as evidence for a man’s body being removed during the ‘break-in’ that occurred soon after the construction of the mound.35 As discussed above, the practice of seiðr could have involved the negotiation of trans identities, either lifelong, or temporally limited in a ritual framework. This, combined with the archaeological evidence, suggests that in the Oseberg burial we are seeing mortuary practices which acknowledge and memorialize a transgender life.

Kaupang Boat Burial, Vestfold, Norway (Ninth to Tenth Centuries)

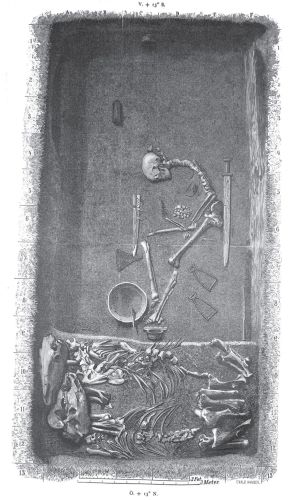

The Kaupang boat burial Ka. 294-296 (the numbers refer to the adult bodies in this burial), also from the Vestfold area, is another example of the funeral process as an ongoing narrative. Here the site extends from the ninth century into the tenth, with the first interment being that of a single man (though it should be noted that most identifications at Kaupang have been made on the basis of grave goods, rather than through osteological sexing) buried there in the ninth century.36 In the following century, a ship was placed on the same site, with its keel aligned with the body underneath. Such an arrangement speaks to the power of memorialization through burial: the original resting place was clearly still alive in the memory of the local community after a considerable period of time, perhaps even after those present at the original funeral were themselves dead, although the dating is too imprecise to be certain of this.37 The tenth-century boat burial contains the bodies of what appears to be a small family: an adult woman at the prow with the remains of an infant laid to rest in her lap, and a man’s body placed in the middle of the boat with his head close to that of the woman. These three individuals were surrounded by a range of grave goods, including silver arm rings, several axes, a sword, and multiple shield bosses. It is the fourth person in the group, however, an individual buried in the stern of the boat, that carries most significance for the present discussion.

Judging by the position of two oval brooches associated with this person, they were buried seated at the steering oar, separated from the other bodies in the grave by the body of a horse. Frans-Arne Stylegar has argued that this person should therefore be viewed as a ritual specialist, given the task of guiding the others in the burial to the afterlife.38 In support of this interpretation is the suggestive positioning of the body: placed in the same burial, but deliberately marked out as separate; connected to the family, but not a part of it. Then there is the position at the steering oar. Unlike the Oseberg ship, the boat at Kaupang was not anchored, lending weight to the idea that, although entombed in earth, it was expected to journey elsewhere on a course set by the person in charge of the steering oar. In addition to this, Neil Price has pointed out that although seated burial is not particularly common in Scandinavian cemeteries, it does occur with relatively high frequency in the graves he identifies as those of potential seiðr practitioners.39

Further evidence comes from the assemblage of grave goods associated with this fourth person, which included a number of unusual items. Perhaps the most obvious of these is an iron staff with a ‘basket handle’. Price identifies staffs of this type as being indicative of the graves of seiðr workers, and Leszek Gardeła concurs that ‘its placement under a stone strongly suggests that it may have been used in magic practices’.40 The twisted prongs of its ‘handle’ together with its symbolic crushing under a stone suggest the ritual ‘killing’ enacted on other metal objects (especially weapons) in the Iron Age, but also recall the treatment of a woman – also frequently identified as a seiðr practitioner – buried at Gerdrup in Denmark, whose body was pinioned under a large rock.41 As with the Oseberg ship, this is a funeral narrative which combines respect and fear.

Evidence for a transgender reading of this burial is less pronounced than at Oseberg. Nevertheless, there are several indicators that this person occupied a highly unusual social position and therefore may have been perceived as being so utterly outside the norms of society that conventional gender identities did not apply. As discussed above, this seems to have been a distinct possibility for seiðr practitioners. In addition to this person’s probable role as a seiðr specialist, several other items in the grave help to create a narrative that tells of a social identity beyond the binary. One of these is the person’s outfit. Though the find of two oval brooches suggests conventional female attire, fragments of animal hide preserved by proximity to the metal of the brooches point to a highly unusual leather costume, perhaps reminiscent of the strange array of catskin and lambskin worn by Thorbjorg, the female seiðr practitioner seen in Eiríks saga rauða.

The separation of the body from the rest of the burial by the body of a horse leaves little doubt that the axe head and shield boss found in the stern should be connected with the figure seated there, rather than with the adult man placed in the middle of the boat. Women’s graves containing axes are not common, though they are also hardly unknown.42 However, the inclusion of a shield boss (presumably once a whole shield, with the wooden part rotted away) is more unusual; such armaments are virtually unknown in female graves. In combination, these two items and the peculiar leather outfit suggest that this burial was deliberately designed to evoke a sense of this person inhabiting a social role outside that of conventional femininity. Other burials in the Kaupang cemetery feature similar objects to those found with the seated figure, but in these other burials, object types in the male and female burials have almost no overlap.43 This lack of overlap suggests that the community who created this grave made a conscious effort to construct distinct memorial narratives for the man and woman buried in Ka. 294-295, perhaps divided down gendered lines. In light of this, then, the presence of oval brooches, metal rods and an iron sword beater (all also found with Ka. 294, the woman in the prow) in combination with an axe head and shield boss (also found with Ka. 295, the man amidships) argues in favour of a memorial narrative for this seiðr practitioner that incorporated elements of masculinity and femininity, but which was also in some ways outside both.44

Klinta Double Cremation, Öland, Sweden (Tenth Century)

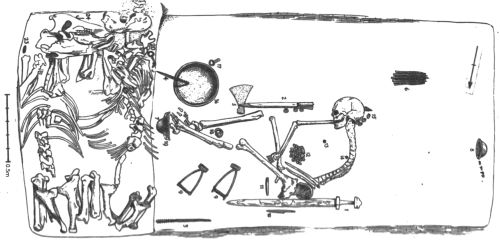

Another grave combining material culture conventionally associated with both masculine and feminine identities is the Klinta double cremation, 59:2 and 59:3, from the island of Öland, off the south-east coast of Sweden. These have been dated to the early tenth century.45 Once again, the level of care that went into this grave represents a significant investment of time and resources from the local community. Again, we see that the funerary process was a long one, consisting of several clear stages, each one contributing to f ix the memory of these individuals in the minds of the participants. The two people cremated at Klinta were burnt together, along with a number of grave goods, on a boat overlaid with bearskins that doubled as their pyre.46 Once the f lames had died, the human remains were washed and placed into separate small pottery containers, each placed in its own grave-pit and surrounded by an array of objects. The act of washing was presumably not a perfunctory hosing-down of the remains, but instead a careful and intimate process, bringing the living into direct physical contact with the dead.

The two cremations appear to deliberately blur the boundaries between the two individuals, whose remains have been osteologically sexed as being those of a man (59:2) and a woman (59:3). This is most apparent in the distribution of grave goods between each grave-pit, where items not conventionally associated with the sexed remains are present in each. In the male grave (59:2), these include a single oval brooch, a bone needle, and sixteen beads.47 In the female grave (59:3), these consist of an axe head – described by Price as a ‘battle-axe’ – and an iron tool for woodworking.48 Early interpretations of the graves concluded that this was an accident, but as Price argues, none of these items are small enough, nor badly dam-aged enough, to have escaped notice during what was clearly a carefully orchestrated process of separating the pyre into two graves.49 Moreover, if the oval brooch found in 59:2 really was intended for 59:3 instead, this would suggest that the latter grave was meant to contain three oval brooches, in itself unusual for an object usually worn in pairs.

The ceramic pot in 59:3, which contained mostly female remains, also contained a small quantity of male remains, presumably those also found in 59:2. Though this has usually been interpreted as an accidental result of the two bodies being burnt together, in light of the ‘mixing’ of graves seen here, it was potentially a deliberate outcome, further mingling these two people in death. In contrast to 59:3, the remains in 59:2 were present in much smaller quantities, which Price argues suggests that the man only needed representing at the grave in a symbolic fashion.50 Rather than viewing these burials as riddled with mistakes – an interpretation that does not do much credit to people at whose depths of ritual knowledge we can only guess – I concur with Price that what we are seeing here is the careful construction of ambiguous gender symbolism in both of these graves.51

Birka Chamber Grave, Björkö, Sweden (Tenth Century)

From the above, it is tempting to conclude that only those deemed super-naturally ‘other’ in some way were able to live transgender or genderqueer lives during the Late Iron Age. However, the tenth-century chamber grave Bj. 581, from the trading site of Birka, provides a counterexample, showing no signs of being the grave of a seiðr practitioner, but nonetheless plausibly being the burial of an individual whose social identity was atypical for their sex. This grave lay near the building often called Birka’s ‘garrison’, which saw violent combat at least once in its life, when it was destroyed by attackers in the late tenth century.52

In addition to its connection with this military building, Bj. 581 is a prototypical ‘warrior’ grave, complete with an array of weapons and rid-ing equipment, even down to the bodies of two horses. Such graves have consistently been gendered as male by excavators, usually in the absence of osteological sexing. This makes it difficult to say how heavily gendered a warrior social identity really was – and by ‘warrior social identity’, I mean that the role of ‘warrior’ was not just a job title, but also a social rank, one that could be held by people who were not involved in combat on a regular basis. Such an interpretation is supported by the large number of ‘warrior’ graves whose occupants do not ever appear to have suffered a severe injury, as well as evidence from early medieval England, where very young children were accorded ‘warrior’ burials, compete with weapons they could never have wielded in life.53 A true picture of the gender balance among ‘warriors’ of this period would require far more extensive osteological or genomic sexing of the remains in weapons-graves than has thus far been carried out, and would still leave the problem that sexed remains cannot tell us anything about an individual’s gender.

Holger Arbman’s report on the material from Bj. 581, the first published work on the grave, confidently declares its occupant to be a man – one of few occasions where this is explicitly noted in his accounts – and subsequent researchers working on the Birka material have largely followed his lead.54 However, over the years several osteologists have raised doubts about the sexing of the bones from Bj. 581, and in 2017 a team of researchers genomically tested the remains and discovered that the deceased almost certainly had XX chromosomes.55 Though the media – and indeed the researchers themselves – were quick to label this individual a ‘female warrior’ and connect them with the shieldmaiden figures popular in later literature, the obvious point should be made that chromosomal analysis cannot tell us anything about a person’s social gender.56 Indeed, without an understanding of gender which recognizes trans identities, advancements in sexing techniques such as those used on the Birka grave run the risk of reinforcing essentialist ideas of the physical body as ultimate arbiter of identity, obscuring the potential complexity of lived experiences in the Iron Age.

There has been considerable debate over the meaning of the so-called ‘warrior’ graves at Birka, but it seems likely, given the violent destruction of Birka’s garrison building, that the person buried in Bj. 581 did have experience using weapons similar to those with which they were buried. Yet the gendering of the warrior role remains in doubt. As noted above, so few graves have been osteologically sexed, as opposed to having gender assigned based on grave goods, that it is impossible to derive a meaningful picture of the assigned-sex-based distribution of weapons in graves, let alone the implications of this for our understanding of Late Iron Age Scandinavian social gender. However, at our current state of knowledge, unambiguous weapons (as opposed to knives and axes, which have non-combat uses) are vanishingly rare in ‘female’ graves in Scandinavia.57 In the absence of a fuller re-examination of weapons-graves across Scandinavia, such objects can be plausibly interpreted as part of a funerary narrative that sought to construct an image of masculine social identity, an identity which, as in the case of Bj. 581, was not always in alignment with modern, binary sexing of the body.

Conclusion

The archaeological material from Iron Age Scandinavia is perhaps most notable for its complexity and diversity. Though individual elements may recur, such as the basket-handled staffs in the seiðr graves discussed above, it is always in combination with new motifs. As such, no two burials are identical in the stories they tell and the way in which they tell them. In the examples given above, humans, animals and objects interact to create narratives, both of the funerary proceedings themselves, and of the surviving community’s memory of the deceased. A deliberate result of these actions was the creation of physical monuments, often on a large scale, which served as a visual trigger for memories of these narratives embedded in the landscape. The narratives presented by the burials discussed here share a common feature: the evocation of a gender system that was more complicated than a simple male/female binary, reliant on anatomy. Our understanding of this system is still limited by the nature of the evidence, which is often fragmentary and subject to a variety of interpretations. In many cases, we are still working within the constraints laid down by archaeologists of the nineteenth century. It is only by bringing a wider range of perspectives to bear on the matter, including approaches which take account of trans identities, that we can begin to overcome the limitations of a binary approach. In this way, we can appreciate more clearly the complexity of gender in the Iron Age, and begin to understand gender in this historical moment – as well as in our own – with greater contextual insight.

Appendix

Endnotes

- See, for example, the inclusion of Thor’s hammer and the ‘valknut’ (a set of three interlocking triangles of uncertain meaning seen on some of the Gotlandic picture stones) on lists of hate symbols (Anti-Defamation League, ‘Database’).

- Southern Poverty Law Center, ‘Neo-Volkisch’.

- On race in the sagas see Cole, ‘Racial Thinking’; Heng, Invention of Race. On the queerness of Norse cosmology see Mayburd, ‘Reassessment’; Normann, ‘Woman or Warrior?’; Solli, Seid; and ‘Queering the Cosmology of the Vikings’. On masculinities and femininities see Bandlien, Man or Monster?; Evans, Men and Masculinities; Jóhanna Katrín Friðriksdóttir, Women; Phelpstead, ‘Hair Today ’.

- On archaeological remains as a meaningful text that can be interpreted, see, for example, Hodder and Hutson, Reading the Past; Hodder, ‘Not an Article’; Patrik, ‘Record?’

- Transgender: adjective referring to someone whose gender identity differs from the gender they were assigned at birth. Genderqueer: adjective describing an experience of gender outside the male/female binary. See the entries for ‘Trans(gender)’ (pp. 316-17) and ‘Genderqueer’ (p. 299) in the Appendix.

- Hedenstierna-Jonson et al., ‘Female Viking Warrior’.

- Several such examples (from outside the period and region under discussion here) are explored in Weismantel (‘Transgender Archaeology’) and Joyce (Ancient Bodies), both of which make a strong case for the validity of transgender readings of the past, and the possibilities such approaches of fer for expanding our understanding in the present.

- See Ghisleni, Jordan, and Fioccoprile, ‘Introduction’; Joyce, Ancient Bodies; Nordbladh and Yates, ‘Perfect Body’; Weismantel, ‘Transgender Archaeology’.

- Skoglund et al., ‘Accurate Sex Identification’, pp. 4479-80.

- ‘Social gender’ as a concept overlaps somewhat with Butler’s description of gender as an iterative performance (Gender Trouble, p. 177), but owes a greater debt to the multifaceted model of gender presented by Serano (Whipping Girl, p. xvi).

- Price, ‘Passing into Poetry’, pp. 123-56; Williams and Sayer, ‘Death and Identity’, p. 3.

- Williams, Death and Memory, p. 4.

- The importance of recognizing non-human agency in the archaeological record has been argued by, among others, Latour (Reassembling the Social, p. 16).

- See Price, ‘Dying and the Dead’, p. 259, for a discussion of underrepresented population groups in the Scandinavian burial record.

- Joyce, Ancient Bodies;Sørensen, Gender Archaeology, pp. 54-59; Weismantel, ‘Transgender Archaeology’.

- Moen, ‘Gendered Landscape’, p. 10; Stylegar, ‘Kaupang Cemeteries’, p. 83.

- Arbman, Birka, p. 188.

- Hedenstierna-Jonson et al., ‘Female Viking Warrior’, p. 857.

- Einar Ól. Sveinsson and Matthías Þórðarson, Eyrbyggja Saga, pp. 206-09.

- ‘Fylgir svá mikil ergi, at eigi þótti karlmǫnnum skammlaust við at fara’. Bjarni Aðalbjarnarson, Heimskringla, p. 19.

- ‘[D]raptu á vétt sem vǫlur […] ok hugða ek þat args aðal’. Jónas Kristjánsson and Vésteinn Ólason, Edduk væði, p. 413.

- Tolley, Shamanism, pp. 487-88.

- Ibid., pp. 581-89.

- See, for example, Price, Viking Wa y, pp. 205-06; Solli, Seid, pp. 159-62.

- Such interpretations tend to take a somewhat simplistic approach to gender, often conflating it with sexuality. See especially Solli, Seid, pp. 151-52. See ‘Two-spirit’ in the Appendix: p. 324.

- Mayburd, ‘Reassessment’, p. 148.

- Price, ‘Passing into Poetry’, pp. 135, 139.

- Price, Viking Way, p. 206. Leszek Gardeła notes the similarity of many of these rods to distaffs; those made of iron would have been too heavy for use in spinning but are plausibly skeuomorphic representations of distaffs ((Magic) Staffs, pp. 176-84).

- Price, Viking Way, p. 160.

- Gansum, Hauger som Konstruksjoner, pp. 172-74; Price, ‘Passing into Poetry’, pp. 138-39.

- Gansum, Hauger som Konstruksjoner, p. 174.

- Holmboe, ‘Oseberghaugens torv’, p. 205; Holmboe, ‘Nytteplanter’, pp. 3-80; Nordeide, ‘Death in Abundance’, p. 12.

- Price, ‘Passing into Poetry’, p. 139.

- Holck, Skjelettene, p. 60.

- Androshchuk, ‘En Man’, pp. 124-6, although see above for caveats regarding the gendering of grave goods. The break-in has been dated to the late tenth century based on the remnants of a wooden spade found abandoned in the grave. Many valuable items were left untouched, but the bodies were disturbed; it has been argued that this was a deliberate, if delayed, part of the funeral. See Bill and Daly, ‘Plundering’, pp. 808-24.

- Stylegar, ‘Kaupang Cemeteries’, p. 82.

- Ibid., p. 95.

- Ibid., p. 99.

- Price, Viking Way, pp. 127-40. It should be noted that Price’s examples come from the Birka cemeteries, where a number of graves apparently unconnected with seiðr workers also feature seated burial (e.g. Bj. 581, discussed below).

- Gardeła, (Magic) Staffs, p. 312; Price, Viking Way, p. 203.

- Gardeła, ‘Buried with Honour’, p. 342; and (Magic) Staffs, p. 217.

- See Gardeła, ‘Warrior Women’, pp. 273-339 for a survey of Scandinavian women’s graves with weapons – although, as Gardeła points out, a number of the graves he discusses were gendered through their grave goods, rather than through any osteological sexing, raising further doubts about what precisely makes these ‘women’s’ graves.

- See Stylegar, ‘Kaupang Cemeteries’, pp. 122-23, for a complete survey of the finds from this burial.

- Gardeła argues that these objects represent an ability to cross gender lines rather than exist outside them: ‘Warrior Women’, p. 290.

- Price, Viking Way, p. 142.

- Petersson, ‘Ett Gravfynd’, pp. 139-41.

- Beads are not unknown in other male graves, however. For example, Ka. 295, the man in the Kaupang boat burial discussed above, was also buried with a number of beads.

- Price, Viking Way, p. 144.

- Petersson, ‘Ett Gravfynd’, p. 139; Price, Viking Way, p. 149.

- Price, Viking Way, p. 147.

- Ibid.

- Hedenstierna-Jonson, ‘Birka Warrior’, p. 69.

- Härke, ‘Warrior Graves?’, pp. 22-43; Pedersen, Dead Warriors, p. 240.

- Arbman, Birka, p. 188; Gräslund, Birka, pp. 10-11.

- Hedenstierna-Jonson et al., ‘Female Viking Warrior’, pp. 855, 857.

- On this, see Price et al., ‘Viking Warrior Women?’, p. 191.

- Gardeła, ‘Warrior Women’, p. 300.

Bibliography

- Androshchuk, Fedir, ‘En Man i Osebergsgraven?’, Fornvännen, 100 (2005), 115-28.

- Anti-Defamation League, ‘Hate on Display Hate Symbols Database’, <https://www.adl.org/hatesymbolsdatabase> [accessed 10 July 2019].

- Arbman, Holger, Birka. Untersuchungen und Studien. I. Die Gräber. Text (Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1943).

- Bandlien, Bjørn, Man or Monster? Negotiations of Masculinity in Old Norse Society (Oslo: Faculty of Humanities, University of Oslo, 2005).

- Bill, Jan, and Aoife Daly, ‘The Plundering of the Ship Graves from Oseberg and Gokstad: An Example of Power Politics?’, Antiquity, 86.333 (2012), 808-24.

- Brink, Stefan, ‘How Uniform Was the Old Norse Religion?’, in Learning and Understanding in the Old Norse World: Essays in Honour of Margaret Clunies Ross, ed. by Judy Quinn, Kate Heslop, and Tarrin Wills (Turnhout: Brepols, 2007), pp. 105-36.

- Butler, Judith, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (London: Routledge, 1990).

- Cole, Richard, ‘Racial Thinking in Old Norse Literature: The Case of the Blámaðr’, Saga-Book 39 (2015), 5-24.

- Evans, Gareth Lloyd, Men and Masculinities in the Sagas of Icelanders (Oxford: Oxford University, 2019).

- Gansum, Terje, Hauger som Konstruksjoner: Arkeologie for ventninger gjennom 200 År (Göteborg: Department of Archaeology, Göteborg University, 2004).

- Gardeła, Leszek, ‘Buried with Honour and Stoned to Death? The Ambivalence of Viking Age Magic in the Light of Archaeology’, Analecta Archaeologica Ressoviensia, 4 (2009), 339-75.

- —, ‘“Warrior-Women” in Viking Age Scandinavia? A Preliminary Archaeological Study’, Analecta Archaeologica Ressoviensia, 8 (2013), 273-339.

- —, (Magic) Staffs in the Viking Age (Vienna: Fassbaender, 2016).

- Ghisleni, Lara, Alexis M. Jordan, and Emily Fioccoprile, ‘Introduction to “Binary Binds”: Deconstructing Sex and Gender Dichotomies in Archaeological Practice’, Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 23 (2016), 765-87.

- Gräslund, Anne-Sofie, Birka. Untersuchungen und Studien. IV. The Burial Customs (Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1980).

- Härke, Heinrich, ‘Warrior Graves? The Background of the Anglo-Saxon Weapon Burial Rite’, Past and Present, 126 (1990), 22-43.

- Hedenstierna-Jonson, Charlotte, ‘The Birka Warrior: The Material Culture of a Martial Society’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, Stockholm University, 2006).

- Hedenstierna-Jonson, Charlotte, Anna Kjellström, Thorun Zachrisson, Maja Krzewińska, Veronica Sobrado, Neil Price, Torsten Günther, Mattias Jakobsson, Anders Götherström, and Jan Storå, ‘A Female Viking Warrior Confirmed by Genomics’, American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 164.4 (2017), 853-60.

- Heng, Geraldine, The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University, 2018).

- Hodder, Ian. ‘This is Not an Article about Material Culture as Text.’ Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 8.3 (1989), 250-69.

- Hodder, Ian, and Scott Hutson, Reading the Past: Current Approaches to Interpretation in Archaeology, 3rd edn (Cambridge: Cambridge University, 2003).

- Holck, Per, Skjelettene fra Gokstadog Osebergskipet (Oslo: University of Oslo, 2009).

- Holmboe, Jens, ‘Nytteplanter og Ugræs i Osebergfundet’, in Osebergfundet, ed. by A.W. Brøgger and Haakon Shetelig, 5 vols. (Oslo: Universitetets Oldsaksamling, 19 2 7), v, 3-80.

- —, ‘Oseberghaugens Torv’, in Osebergfundet, ed. by A.W. Brøgger, Hj. Falk, and Haakon Shetelig, 5 vols. (Oslo: Universitetets Oldsaksamling, 1917), i, 201-05.

- Jóhanna Katrín Friðriksdóttir, Women in Old Norse Literature: Bodies, Words, and Power, New Middle Ages (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013).

- Joyce, Rosemary A., Ancient Bodies, Ancient Lives: Sex, Gender, and Archaeology (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2008).

- Latour, Bruno, Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network Theory (New York: Oxford University, 2007).

- Mayburd, Miriam, ‘“Helzt þóttumk nú heima í millim…”: A Reassessment of Hervör in Light of Seiðr’s Supernatural Gender Dynamics’, Arkiv för Nordisk Filologi, 129 (2014), 121-64.

- Moen, Marianne, ‘The Gendered Landscape. A Discussion on Gender, Status and Power Expressed in the Viking Age Mortuary Landscape’ (unpublished master’s thesis, University of Oslo, 2010).

- Nordbladh, Jarl, and Timothy Yates, ‘This Perfect Body, This Virgin Text’, in Archaeology After Structuralism: Post-Structuralism and the Practice of Archaeology, ed. by Ian Bapty and Timothy Yates (London: Routledge, 1990), pp. 221-37.

- Nordeide, Sæbjørg Walaker, ‘Death in Abundance – Quickly! The Oseberg Ship Burial in Norway’, Acta Archaeologica, 8.1 (2011), 8-15.

- Normann, Lena, ‘Woman or Warrior? The Construction of Gender in Old Norse Myth’, in Old Norse Myths, Literature and Society. Proceedings of the 11th International Saga Conference, 2-7 July 2000, University of Sydney, ed. by Geraldine Barnes and Margaret Clunies Ross (Sydney: Centre for Medieval Studies, 2000), pp. 375-85.

- Patrik, Linda E., ‘Is There an Archaeological Record?’, Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory, 8 (1985), 27-62.

- Pedersen, Anne, Dead Warriors in Living Memory. A Study of Weapon and Equestrian Burials in Viking-Age Denmark, AD 800-1000 (Copenhagen: University of Southern Denmark and the National Museum of Denmark, 2014).

- Petersson, K.G., ‘Ett Gravfynd fran Klinta, Kopingssn., Oland’, Tor, 4 (1958), 134-50.

- Phelpstead, Carl, ‘Hair Today, Gone Tomorrow: Hair Loss, the Tonsure and Medieval Iceland’, Scandinavian Studies, 85.1 (2013), 1-19.

- Price, Neil, Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson, Thorun Zachrisson, Anna Kjellström, Jan Storå, Maja Krzewińska, Torsten Günther, Verónica Sobrado), Mattias Ja-kobsson, and Anders Götherström, ‘Viking Warrior Women? Reassessing Birka Chamber Grave Bj. 581’, Antiquity, 93.367 (2019), 181-98. <https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2018.258> [accessed 11 August 2020].

- Price, Neil S., ‘Dying and the Dead: Viking Age Mortuary Behaviour’, in The Viking World, ed. by Stefan Brink and Neil S. Price (London: Routledge, 2008), pp. 257-73.

- —, ‘Passing into Poetry: Viking-Age Mortuary Drama and the Origins of Norse Mythology’, Medieval Archaeology, 54 (2010), 123-56.

- —, The Viking Way. Religion and War in Late Iron Age Scandinavia (Uppsala: Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, Uppsala University, 2002).

- Serano, Julia, Whipping Girl: A Transsexual Woman on Sexism and the Scapegoating of Femininity, 2nd edn (New York: Seal, 2016).

- Skoglund, P., J. Storå, A. Götherström, and M. Jakobsson, ‘Accurate Sex Identification of Ancient Human Remains Using DNA Shotgun Sequencing’, Journal of Archaeological Science, 40 (2013), 4477-82.

- Solli, Brit, ‘Queering the Cosmology of the Vikings: A Queer Analysis of the Cult of Odin and “Holy White Stones”’, Journal of Homosexuality, 54.1/2 (2008), 192-208.

- —, Seid: Myter, sjamanisme og kjønn i vikingenes tid (Oslo: Pax, 2002).Sørensen, Marie Louise Stig, Gender Archaeology (Cambridge: Polity, 2000).

- Southern Poverty Law Center, ‘Neo-Volkisch’ <https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files/ideology/neo-volkisch> [accessed 10 July 2019].

- Stylegar, F.-A., ‘The Kaupang Cemeteries Revisited’, in Kaupang in Skiringssal, ed. by Dagfinn Skre, Norske Oldfunn, 22 (Aarhus: Aarhus University, 2007), pp. 65-128.

- Tolley, Clive, Shamanism in Norse Myth and Magic, 2 vols. (Helsinki: Academia Scientiarum Fennica, 2009), i.

- Weismantel, Mary, ‘Towards a Transgender Archaeology. A Queer Rampage Through Prehistory’, in The Transgender Studies Reader 2, ed. by Susan Stryker and Aren Z. Aizura (New York: Routledge, 2013), pp. 319-34.

- Williams, Howard, Death and Memory in Early Medieval Britain (Cambridge: Cambridge University, 2006).

- Williams, Howard, and Duncan Sayer, ‘“Halls of Mirrors”: Death and Identity in Medieval Archaeology’, in Mortuary Practices and Social Identities in the Middle Ages. Essays in Burial Archaeology in Honour of Heinrich Härke, ed. by Howard Williams and Duncan Sayer (Exeter: University of Exeter, 2009), pp. 1-22.

Chapter 7 (177-196) from Trans and Genderqueer Subjects in Medieval Hagiography, edited by Alicia Spencer-Hall and Blake Gutt (Amsterdam University Press, 04.06.2021), published by OAPEN under the terms of an Open Access license.